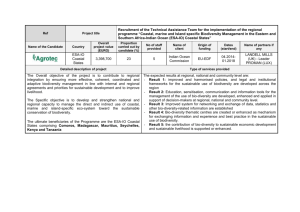

Project Concept Note - Global Environment Facility

advertisement

Document of

The World Bank

Report No: 31307 - NA

PROJECT BRIEF

ON A

PROPOSED GRANT FROM THE

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND

IN THE AMOUNT OF US 4.9 MILLION

TO THE

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA

FOR A

NAMIB COAST BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT

{02/09/05}

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS

(Exchange Rate Effective February 2005)

Currency Unit = Namibia Dollar

1NAD = US$ 0.161

US$1 = NAD 6.19

FISCAL YEAR

April 1 – March 31

AFR

ASPEN

BCC

BCLME

BENEFIT

BP

BTOR

CAS

CBD

CBNRM

CBO

CBT

CCD

CEM

CEO

CEPF

CFA

COP

CZM

DANCED

DAP

DDC

DEA

DIP

DLIST

DO

DPWM

DRFN

EA

EC

EEZ

EIF

ELAK

EMB

EMP

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Africa Region

Africa Safeguard Policies Enhancement

Benguela Current Commission

Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem

Benguela Environment Fisheries Interaction and Training Programme

Bank Procedure

Back to Office Report

Country Assistance Strategy

Convention on Biological Diversity

Community Based Natural Resource Management

Community Based Organization

Community Based Tourism

Convention to Combat Desertification

Country Economic Memorandum

Chief Executive Officer

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund

Counterpart Fund Account

Conference of the Parties

Coastal Zone Management

Danish Agency for Cooperation and Development

Decentralization Action Plan

Directorate of Decentralization Coordination

Directorate of Environmental Affairs

Decentralization Implementation Plan

Distance Learning Information Sharing Tool

Development Objective

Directorate of Parks and Wildlife Management

Desert Research Foundation in Namibia

Environmental Assessment

European Commission

Exclusive Economic Zone

Environmental Investment Fund

Environmental Learning and Action in the Kuiseb

Environmental Management Bill

Environmental Management Plan

EMS

EOP

ESW

EU

FCCC

FP

FY

GDP

GEF

GIS

GRN

GTRC

GTZ

HDI

HWM

IBRD

ICB

ICEMA

ICR

ICZM

ICZMC

IDA

IEC

IEM

IMCAM

IP

IT

IUCN

LA

LD

LM

M&E

MAWRD

MDG

MENA

MET

MFMR

MLRR

MME

MoU

MPA

MRLGH

MSP

MTR

MWTC

NACOBTA

Environmental Management System

End of Project

Economic and Strategic Work

European Union

Framework Convention on Climate Change

Focal Point

Fiscal Year

Gross Domestic Product

Global Environment Facility

Geographic Information Systems

Government of the Republic of Namibia

Gobabeb Training and Research Centre

German Technical Cooperation

Human Development Index

High Water Mark

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

International Competitive Bidding

Integrated Community-based Ecosystem Management Project

Implementation Completion Report

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Integrated Coastal Zone Management Committee

International Development Agency

Information, Education, Communication

Integrated Ecosystem Management

Integrated Marine and Coastal Area Management

Implementation Progress

Information Technology

International Union for the Conservation of Nature

Local Authority

Land Degradation

Line Ministry

Monitoring and Evaluation

Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development

Millennium Development Goal

Middle East and North Africa

Ministry of Environment and Tourism

Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources

Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation

Ministry of Mines and Energy

Memorandum of Understanding

Marine Protected Area

Ministry of Regional and Local Government and Housing

Medium-Size Project

Mid-Term Review

Ministry of Water, Transport and Communication

Namibian Community Based Tourism Association

NACOMA

NACOWP

NAD

NaLTER

NAMETT

NAPCOD

NatMIRC

NBRI

NBSAP

NCSA

NDP

NEPAD

NGO

NMN

NPA

NPC

NRM

OP

ORMIMC

PA

PA

PAD

PCD

PDF

PDO

PESILUP

PGO

PHRD

PIC

PIM

PMU

PPP

PPP

PTO

RC

RDCC

RDP

REO

RVP

SA

SADC

SBD

SC

SG

SKEP

Namib Coast Biodiversity Conservation and Management Project

Namibia Coastal Management White Paper

Namibia Dollar

Namibian Long Term Ecological Research

Namibian Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool

National Program to Combat Desertification

National Marine Information and Research Centre

National Botanical Research Institute

National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

National Capacity Self Assessment

National Development Plan

New Partnership for Africa’s Development

Non-Governmental Organization

National Museum of Namibia

Strengthening the System of National Protected Areas Project

National Planning Commission

Natural Resource Management

Operational Program

Orange River Mouth Interim Management Committee

Protected Area

Project Account

Project Appraisal Document

Project Concept Document

Project Development Fund

Project Development Objective

Promoting Environmental Sustainability Through Improved Land Use Planning

Project

Project Global Objective

Japan Policy and Human Resources Development Fund

Public Information Center

Project Implementation Manual

Project Management Unit

Project Participation Plan

Public-Private Partnership

Permission to Occupy

Regional Council

Regional Development Coordination Committee

Regional Development Plan

Regional Environmental Office

Regional Vice President

Special Account

Southern Africa Development Community

Standard Bidding Document

Steering Committee

Scientific Group

Succulent Karoo Ecosystem Plan

SoE

SSA

STAP

SWAPO

TA

TFCA

TOR

UNAM

UNDP

USAID

WA

WB

WBI

WEHAB

WHS

WSSD

WWF

Statement of Expenditures

Sub-Saharan Africa

Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel

South West Africa People’s Organization

Technical Assistance

Transfrontier Conservation Area

Terms of Reference

University of Namibia

United Nations Development Programme

United States Agency for International Development

Withdrawal Application

World Bank

World Bank Institute

Water and Sanitation, Energy, Health, Agriculture and Biodiversity

World Heritage Site

World Summit on Sustainable Development

World Wildlife Fund

Vice President:

Country Director:

Sector Manager:

Task Team Leader:

Gobind T. Nankani

Ritva S. Reinikka

Richard G. Scobey

Christophe Crepin

NAMIBIA

Namib Coast Biodiversity Conservation and Management Project

CONTENTS

Page

A.

STRATEGIC CONTEXT AND RATIONALE ................................................................. 8

1.

Country and sector issues.................................................................................................... 8

2.

Rationale for Bank involvement ....................................................................................... 13

3.

Higher level objectives to which the Project contributes.................................................. 14

B.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................... 16

1.

Financial modality ............................................................................................................ 17

2.

Project development (and global) objective ..................................................................... 17

3.

Project components ........................................................................................................... 17

4.

Lessons learned and reflected in the Project design ......................................................... 24

5.

Alternatives considered and reasons for rejection ............................................................ 27

C.

IMPLEMENTATION ........................................................................................................ 28

1.

Partnership arrangements .................................................................................................. 28

2.

Institutional and implementation arrangements ................................................................ 28

3.

Monitoring and evaluation of outcomes/results ................................................................ 30

4.

Sustainability and replicability ......................................................................................... 31

5.

Critical risks and possible controversial aspects ............................................................... 34

6.

Grant conditions and covenants ........................................................................................ 36

D.

APPRAISAL SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 36

1.

Economic and financial analyses ...................................................................................... 36

2.

Technical ........................................................................................................................... 37

3.

Fiduciary ........................................................................................................................... 38

4.

Social................................................................................................................................. 38

5.

Environment ...................................................................................................................... 39

6.

Safeguard policies ............................................................................................................. 40

7.

Policy exceptions and readiness........................................................................................ 40

Annex 1: Country and Sector Background .............................................................................. 41

Annex 2: Major Related Projects Financed by the Bank and/or other Agencies ................. 50

Annex 3: Results Framework and Monitoring ........................................................................ 58

Annex 4: Detailed Project Description ...................................................................................... 72

Annex 5: Project Costs ............................................................................................................... 86

Annex 6: Implementation Arrangements ................................................................................. 87

Annex 7: Financial Management and Disbursement Arrangements ..................................... 95

Annex 8: Procurement Arrangements ...................................................................................... 96

Annex 9: Economic Analysis of Natural Resources of the Namib Coast ............................... 99

Annex 10: Safeguard Policy Issues .......................................................................................... 104

Annex 11: Project Preparation and Supervision ................................................................... 107

Annex 12: Documents in the Project File ............................................................................... 109

Annex 13: Statement of Loans and Credits ............................................................................ 111

Annex 14: Country at a Glance ............................................................................................... 112

Annex 15: Incremental Cost Analysis ..................................................................................... 114

Annex 16: STAP Roster Review .............................................................................................. 129

Annex 17: MAPS ....................................................................................................................... 141

Annex 18: Biodiversity Assets, Threats and Root Causes for Biodiversity Loss and

Proposed Interventions ............................................................................................................. 142

Annex 19: Decentralization in Namibia: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation and

Sustainable Use on the Coast ................................................................................................... 163

Annex 20: Project Participation Plan ..................................................................................... 169

A. STRATEGIC CONTEXT AND RATIONALE

1. Country and sector issues

Namibia’s coastal zone

1.

The hyper-arid Namibian coastal ecosystem, which stretches from the Kunene River on

the northern border to the Orange River on the southern border, is home to a significant and

unique array of biological and ecological diversity, including uniquely adapted plants and

animals, rich estuarine fauna and a high diversity of migratory wading and seabirds. The Namib

Desert runs along the entire 1,500 km of the coast, extending beyond the Orange River into the

northwestern corner of South Africa – an area known as the Richtersveld – and beyond the

Kunene River into the southwestern corner of Angola. Although much of the coast consists of

sandy beaches with isolated outcrops, there are also significant lagoons, estuaries and riverbeds.

Because the region, which is isolated between the ocean and the escarpment, is a constant island

of aridity surrounded by a sea of climatic change, it has remained a relatively stable center for

the evolution of numerous desert species. The Succulent Karoo biome of the southern Namib

Desert has more diversity than any other desert in the world. (Exceptional features of the

Namibian coast at the ecosystem level are discussed further in Annex 18.)

2.

These rich coastal ecosystems are extremely fragile and can easily be disturbed by human

activities. The coastal region has been relatively inaccessible to date, and there have been few

opportunities for use of coastal land and resources by residents of coastal regions. As a result,

Namibia has an exceptionally low, and geographically very concentrated, coastal population

compared to other countries. However, increasing human pressures over the past several years

highlight the urgent need for sound coastal planning and management to ensure sustainable and

optimal use of coastal areas and their resources in the future.

3.

The main sources for economic development in Namibia, in particular within the four

coastal regions (Hardap, Karas, Erongo and Kunene), are all resource-based, including a rapidly

growing nature-based tourism industry1, an overall expanding extractive industry (oil and gas

exploration and off-shore mining of minerals, although diamond mining and processing is mostly

downscaling), and a strong commercial fishing industry with growing aquaculture. Farming or

other agricultural activity is almost precluded as a livelihood option, due to the hyper-arid

climate of the coastal desert. Growing economic development and human activities along the

coast may lead to unprecedented migration to the region, bringing with it uncontrolled urban

development that can result in overuse and pollution of freshwater resources, an increase in

industrial coastal and marine pollution, degradation of water regimes for coastal wetlands, and

other land and water degradation.2 (see Annex 18 for more information on threats and root

causes).

4.

If allowed to remain unchecked and unplanned, this development will result in long-term

loss of biodiversity, ecological functioning and, contrary to the national poverty eradication

1

Namibian Wildlife Resorts based in the coastal zone rank high among 18 primary tourism destinations: Cape Cross

2nd, Namib Naukluft 3rd, Hardap 6th, West Coast 12th and Skeleton 13th.

2

MAWRD estimates that Namibia’s internal water resources will be exhausted by 2020.

8

objectives, a reduction of the economic potential of the coast itself. This possibility presents the

greatest potential challenge to the expanding nature-based tourism industry, which depends upon

a healthy environment for its success. Tourism has proven so popular along the Namibian coast

that, in high season, the region’s population nearly doubles, as tourists from South Africa,

Germany and other countries arrive to enjoy the unique and relatively pristine coastal habitats.

Environmental degradation and habitat conversion can destroy the very features that draw

tourists, resulting in both a loss of global biodiversity and lost local economic opportunities.

5.

These growing threats are exacerbated by the lack of integrated conservation and

development planning in the Namibian coastal region, coupled with poor management of

resources in the face of increased pressures. For example, despite the serious threat to water

supply and quality, there is currently no integrated water management system; nor is there any

available assessment of the principal economic activities, in terms of their socio-economic and

environmental costs and benefits. This lack of sound economic and environmental baseline data

makes it difficult for national, regional and local government to agree on how to define a

sustainable coastal zone development framework, including the promotion of diversified

livelihood options for coastal populations (see Annex 9).

National and regional development goals

6.

The Government of the Republic of Namibia’s (GRN) medium-term vision is to

transform itself from a developing lower-middle-income country into an industrially developed

high-income country by the year 2030.3 Achievement of this vision is guided by the “Namibia

Vision 2030 Policy Framework for Long Term National Development” – a broad, unifying

“targets list” that guides five-year National Development Plans (NDPs). The current plan, NDP 2

(for 2001/02-2005/06) targets poverty reduction, sustainable development of rural areas, the

provision of health services to the majority of the population and the strengthening of human

capital.

7.

NDP 2 is the first development plan to include a volume dealing specifically with

regional development issues - the Regional Development Plans (RDPs). Since Independence,

Namibia has made slow but steady progress in moving away from a very nationalized approach,

rooted in the apartheid regime, toward decentralization (see Annex 19). Development planning in

Namibia now takes place at three levels: national, sectoral and regional, and NDP 2 includes

objectives such as strengthening capacity building at the regional level, ensuring effective

decentralized regional planning based on participatory approaches and optimizing the use of

regional potentials.

8.

However, the current situation in Namibia demonstrates that there is a gap between these

guiding strategies and the economic, environmental and institutional reality in the country.

Decentralization progress has been much slower than anticipated; poverty levels are still very

high (about 56 percent of the 1.83 million Namibians have been designated as poor or very

3

Namibia ranks as a LMI (Lower Middle-Income) Country (based on GDP per capita), 68 th out of 173 countries,

and as a Medium Human Development (MHD) Country (based on Human Development Index), 122 nd out of 173

countries. Its Government Effectiveness Index shows the 3 rd highest score of all MHD countries. Its law and order

score is the best possible, and it has the lowest level of corruption of any MHD country.

9

poor4); national economic growth is heavily dependent on one resource-based activity, the

mining industry, with minimal opportunities for creation of employment and benefits for the rest

of the economy and potentially negative environmental impacts; and the divide between rural

and urban, northern and southern regions, and rich and poor persists and is even growing.

Government strategy for sustainable development of the coastal zone

9.

The Namib Coast Biodiversity Conservation and Management Project (NACOMA) is

part of the GRN’s strategy to promote sustainable economic development in the coastal zone and

address its local, regional, national and global environmental priorities. Two key elements of the

Government’s environmental strategy are its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

(NBSAP), developed under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and Namibia’s

Action Plan to Combat Desertification (NAPCOD), as submitted to the Convention to Combat

Desertification (CCD). The NBSAP highlights the need for support for currently under-protected

key biodiversity hotspots, adequate input into the process of zoning, development of guidelines

and environmental assessment of proposed aquaculture developments, and inclusion of relevant

NBSAP components into the RDPs (see Annex 4). Within NAPCOD, targeted investments,

capacity building and enhancement of decentralization are regarded as key elements for halting

land degradation.

10.

The Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) plans to merge the biodiversity and

desertification Programs, in order to foster synergies and focus on integrated approaches for

natural resource management, bio-trade and desert research. MET is supporting a capacitybuilding program related to NAPCOD and NBSAP for key stakeholders, and Integrated Coastal

Zone Management (ICZM) is expected to be included among the identified priority themes. A

few other complementary donor-funded projects and programs aim to conserve coastal and

marine biodiversity in and outside biodiversity hotspots and conservation areas, and to

strengthen capacity to accelerate and improve the decentralization process (see Annex 2).

11.

The Government has identified three key gaps in its overall strategy and resources, for

which it seeks support: development of environmental legislation, progress on

decentralization and creation of an institutional framework for ICZM:

(i) Environmental legislation

12.

Namibia currently has no modern legislation on integrated water management,

biodiversity conservation/protected area management or environmental aspects of mining,

although draft laws are under consideration. In addition, although Namibia has a range of

sectoral policies and strategies that deal with natural resource management, biodiversity and

other coast-related matters, the mainstreaming of cross-cutting issues (such as biodiversity

conservation) into these sectoral policies, strategies and implementation activities at the national,

regional and local levels – as proposed and planned under the NBSAP and other strategies – is

still a distant goal.

4

Source: Draft CEM Namibia 2004.

10

13.

A major long-awaited piece of legislation, the draft Environmental Management and

Assessment Bill (EMB), would incorporate Environmental Impact Assessment procedures into

Namibian law. However, it is not clear how far the EMB’s provisions would apply to sectoral

coastal projects that could threaten Namibia’s coastal integrity, and there is no indication of

whether the EMB will provide for strategic environmental assessment of relevant policies and

plans in line with international best practices (e.g. under the CBD).

Other key issues in the GRN’s relevant draft legislation include:

1. Planning and decision-making for potentially damaging activities within protected areas

(MET/MME/MWTC/MFMR/MLRR);

2. Conservation of biodiversity outside formally designated areas (e.g. at the regional

landscape scale), and use of ecological corridors and buffer zones (MET/MAWRD);

3. Possibility of mixed terrestrial/marine protected areas (MET/MFMR);

4. Transboundary cooperation on area and species management (MET); and

5. Protection of threatened and endangered marine species (MET/MFMR).

14.

The Government seeks to undertake a legal and policy review of its current legislative

and regulatory framework, to identify areas for potential adjustment, modernization and

harmonization of that legislation.

(ii) Decentralization

15.

The Government’s ongoing decentralization process is an important component of

strengthening regional and local development and promoting sustainable management of coastal

resources. Currently, planning, implementation and assessment of coastal zone issues is

fragmented and under the authority of several central line ministries, including MET, the

Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR), the Ministry of Regional and Local

Government Housing (MRLGH), the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME), the Ministry of

Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation (MLRR), the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural

Development (MAWRD) and the Ministry of Water, Transport and Communication (MWTC).

At the same time, regional and local authorities5 operate without a clear legal framework and

with overlapping mandates and limited funds. Regional Councils (RCs), local authorities (LAs)

and line ministries’ field staff lack the human, technical and financial capacity to undertake their

duties as currently defined (see Annex 19).

16.

Centralized control has also impacted resource protection efforts along the coast. A

significant portion of the coastline has been designated as protected area, mainly before

Independence, although levels of protection have been uneven, and in some areas clearly

insufficient. These designations have meant that there is an unusually high level of nationalized

control and an unusually low level of regional and local authority involvement in coastal land

management.

17.

Despite the slow progress to date, the government continues to officially reconfirm its

commitment to advancing its decentralization agenda, with the ultimate goal of devolution.

Positive results over the past year have included: (i) clarification of the development and

5

The main local authorities/government in the coast are Swakopmund, Walvis Bay, Henties Bay and Lüderitz.

There are also many smaller municipalities, “autonomous” villages and settlements.

11

planning mandates of RCs and inclusion of those critical functions in the RDPs; (ii) revision of

the Regional Council Organization Structure to accommodate functions to be decentralized; and

(iii) preparation of two donor-funded decentralization support projects. However, to date only a

few planning officers have been recruited, and Line Ministry Action Plans pertaining to the

decentralized functions of the relevant Ministries have yet to be developed and implemented

(e.g. MET). Thus, despite the need and expressed desire for an integrated conservation and

development approach to regional planning, environmental concerns are currently poorly

incorporated in RDPs, and environmental planning and management (through community-based

natural resource management (CBNRM) and community-based forestry) are proposed but, in

practice, still absent.

18.

The GRN’s strategy to empower previously disadvantaged Namibians and facilitate the

decentralization of natural resource management and biodiversity conservation includes

development of a comprehensive coastal management policy process to provide for the transition

from national to regional and local planning and management, and concurrent institutional and

capacity building of the regional and local government machinery, its partners in civil society

and other associated players (see Annex 19).

(iii) Institutional framework for ICZM

19.

A key entity for coastal resource management in Namibia is the Integrated Coastal Zone

Management Committee (ICZMC),6 which was established by the four coastal RCs from a small

ICZM project in the Erongo Region (see Annex 2). The ICZMC, which is governed by the

National Council, Regional Councils, Local Authorities and Council of Traditional Leaders,

seeks to develop a common approach to sustainable development of the coastal zone, share

lessons learned and seek inter-regional synergies. The committee co-exists with other structures

for cooperative management and sustainable utilization of shared border rivers.7 At sea, the

BCLME Programme is investigating the need for and feasibility of a Benguela Current

Commission (BCC) that could provide for synergetic linkages to the ICZMC (see Annex 6).

20.

Nevertheless, the current ICZMC lacks technical and financial capacity and a clear

political and functional mandate. The committee needs to be substantially strengthened through a

strong enabling environment, targeted capacity building and targeted membership, in order to

create a sustainable and well-connected coastal zone management institution to spearhead

conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

21.

The GRN also recognizes the need for a common vision for all stakeholders about the

sustainable use and management of biodiversity and coastal zone resources. Such a vision is

currently absent, due to the lack of sufficient information about the environmental and economic

situation of the Namib coast and the four administrative coastal regions and their contribution to

national and regional development. In addition, the weak or non-existent coordination, both

6

The ICZMC currently consists of the four regional governors, four national councilors and the four Chief

Executive Officers. Additionally, the ICZMC includes line ministry officials from MET, MRLGH, MME and

MFMR.

7

Permanent Joint Technical Commission on the Kunene River (Namibia-Angola 1990) and Permanent Water

Commission on the Orange River (Namibia-South Africa 1992).

12

among regions and between local and regional, and regional and national, decision-makers

hampers the development of a common vision and strategy. This is particularly a problem in the

interface between the regional and local levels, and is a critical issues to be addressed, because of

the rapid growth of coastal towns, the autonomy of the urban growth poles and their proximity to

biodiversity hotspots.

22.

A common vision, together with a new Coastal Zone Management Policy Framework and

a strengthened ICZMC, will provide a basis to ensure policy consistency throughout the coastal

ecosystem. This is essential for activities with potentially long-distance impacts (e.g.

maintenance of coastal fisheries nursery and spawning areas, choice of fish stock for

aquaculture, extraction and mining projects) that could affect erosion and soil deposition

regimes.

2. Rationale for Bank involvement

23.

The Bank, as the GEF Implementing Agency and with its solid experience with ICZM

Projects worldwide, has been requested by the four coastal regions (represented by the ICZMC),

MRLGH and MET to support national and regional strategic efforts toward the development and

implementation of decentralized biodiversity and coastal conservation, and inter-sectoral

cooperation and coordination.

24.

The Bank’s involvement in Namibia has focused on technical assistance to support the

government’s efforts to reduce poverty, to support decentralization and local development, to

analyze various sources of growth, and to identify suitable options to strengthen human capital

development, including knowledge management. Of relevance for the NACOMA design are the

Bank's successful experiences as lead agency of a multi-donor initiative supporting the GRN in

the development of a strongly participatory and high-quality White Paper on National Water

Policy and Water Resources Management Bill.

25.

The Project will build on and make further contributions to these activities, as it aims to

develop capacity for coastal zone management that will spearhead conservation and sustainable

use of biodiversity at the national, regional and local levels; provide financial support to coastal

zone development plans; encourage diversification of growth sources; support mainstreaming

and decentralization of biodiversity conservation-related functions; and support the participation

of a broad range of stakeholders in development of the country’s coastal zone policy. The

continuous environmental dialogue between the Bank and the GRN on the management of

Namibia’s valuable natural resources, and in particular its environmental assets, has already led

to the preparation of two other operations.8 Other environmental support to date includes GEF

Focal Point support and technical assistance for targeted environmental studies. In addition, the

Bank has been requested to provide support for Economic Sector Work on identifying best land

management practices for environmental sustainability. It has also supported, through the World

Bank Institute (WBI), a GEF International Waters pilot initiative, Distance Learning Information

8

These are the Integrated Community-based Ecosystem Management (ICEMA) Project, launched in November

2004, and the Promoting Environmental Sustainability through Improved Land Use Planning (PESILUP) Project,

currently under preparation.

13

Sharing Tool (DLIST)9, which aims to facilitate knowledge sharing, make available distance

learning options in ICZM, identify linkages, and strengthen stakeholder communication and

ground level institutions mainly related to the BCLME and associated coastal areas. Finally,

specific capacity-building synergies are expected between the NACOMA Project and the Bank’s

Sub-National Government Project, which is currently under preparation (see Annex 2).

3. Higher level objectives to which the Project contributes

National objectives

26.

NACOMA will contribute to the objectives of NDP 210 and Vision 2030, including

cross-cutting issues such as enabling capacity-building of stakeholders and institutions and, most

importantly, environmental sustainability. In particular, the Project will support efforts under

NDP 2 to mainstream biodiversity conservation and sustainable use in the emerging

decentralization process by developing the relevant institutional capacities of regional and local

government as well as key national level players.

27.

The Rural Profile and Strategic Framework (RPSF), prepared by the Namibia

National Planning Commission with the European Union (EU) as a governing framework for

rural development programs in Namibia, identifies decentralization of rural institutions as a key

area that requires the close attention of the Government. The Project will address the issue of

decentralization of biodiversity conservation and sustainable use-related functions by serving as

a pilot for decentralization of specific functions of the MET and contributing strongly to

implementation of the MET Directorate of Environmental Affairs’ (DEA) biodiversity and

desertific ation programs in coastal areas.

28.

While there is no country assistance strategy (CAS) for Namibia at present, the Bank is

working with the Government of Namibia to prepare a Country Economic Memorandum

(CEM) that will support the Government’s objectives by providing in-depth analysis and

guidance to develop a pro-poor growth strategy to address concerns related to inequality as well

as growth. Such a framework would also strengthen the partnership between the Bank and

Namibia and form the basis for addressing the key challenges of achieving sustainable growth

and reducing poverty and inequality, by capitalizing on the achievement of the Government and

the comparative advantages of the Bank. The NACOMA Project is in line with the CEM

framework, as it contributes to the dialogue between the Bank and the GRN, promotes the

building of capacity among national and local governments and broadens the income base within

the coastal regions.

World Bank and GEF objectives

29.

NACOMA corresponds to the Africa Region’s strategic directions for coastal and marine

environmental management, as it acts to remove barriers to conservation of fragile coastal and

9

www.dlist.org

It is expected that throughout and even after NACOMA’s implementation phase, integrated coastal zone

management will become a component of NDP 3 and associated RDPs.

10

14

marine ecosystems through adaptive management, learning and information sharing,

strengthening the institutional core and improving the quality of life of local communities.

30.

The activities of the Project are also fully consistent with the priorities of the GEF

Operational Program 2 (OP2) for Coastal, Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. Specifically, the

Project is compatible with OP2’s opportunities to promote the conservation and sustainable use

of biological diversity of coastal and marine resources under threat, and to promote the

conservation of biodiversity and sustainable use of its components in environmentally vulnerable

areas. The Project will do so by focusing on:

i) Promoting the use of integrated marine and coastal zone management as the most suitable

framework for addressing mainstreaming and conservation of marine and coastal biodiversity

and for promoting its conservation and sustainable use (in conjunction with UNDP/NPA Project

and UNDP/BCLME Programme – see Annex 2);

ii) Establishing and strengthening of systems of conservation areas including MPAs (in

conjunction with UNDP/NPA Project and UNDP/BCLME Programme – see Annex 2)11;

iii) Applying a transboundary ecosystem approach to marine and coastal zone management;

iv) Addressing identified driving forces determining status and trends of coastal and marine

biodiversity;

v) Linking to national, regional and local development and conservation priorities and objectives

as defined in the Vision 2030, NDP 3, NBSAP, RDPs, local agenda 21 and environmental

management plans and other related documents;

vi) Building capacity among stakeholders in coastal regions related to integrated coastal zone

planning, management and monitoring;

vii) Promoting targeted survey and management activities for identifying particular coastal and

marine areas that should be conserved to represent major habitat types and their species; and

viii) Raising environmental awareness among all stakeholders.

31.

Further, the Project responds to GEF's crosscutting and biodiversity as well as capacitybuilding strategic priorities as outlined in its Strategic Business Plan FY04-FY06. In line with

GEF’s Biodiversity Strategic Priority 2 (Mainstreaming Biodiversity in Production Landscapes

and Sectors), the Project will facilitate the mainstreaming of biodiversity conservation within

production systems that may threaten biodiversity (mainly tourism, mining, fisheries) by

fostering broad-based integration of biodiversity conservation within the country’s development

agenda. This integration would be achieved through the development of systemic and

institutional capacities of line ministries, regional councils and local authorities, targeted

investments in biodiversity conservation and creation of an enabling environment based on a

joint national vision for the coast, as well as through the project implementation arrangements. In

line with GEF’s Biodiversity Strategic Priority 1 (Catalyzing Sustainability of Protected Areas),

the Project will facilitate biodiversity conservation through the expansion and rationalization of

the National Protected Areas on the coast (see Map in Annex 17) by means of the establishment

of the first Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and their embedment in national and local

legislation, as well as through capacity-building and targeted investments for improved

management.

11

NACOMA will deal with regional scale mainstreaming of coastal and marine conservation areas, whereas the

NPA Project under preparation deals holistically with the national system of terrestrial Protected Areas.

15

Global objectives

32.

The Project follows guidance from the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the CBD, as it

addresses in situ conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and, more importantly,

multiple-use, system-oriented modes of coastal ecosystem management principles. The

Convention, in its decision II/10, adopted by the COP at its second meeting in Jakarta in

November 1995, encouraged the wide adoption and implementation of Integrated Marine and

Coastal Area Management (IMCAM) as a means for effective conservation and sustainable use

of marine and coastal biological diversity. It describes IMCAM as the most suitable participatory

framework for addressing human impacts (prevention, control or mitigation) on marine and

coastal biological diversity and for promoting its conservation and sustainable use. It also

encourages Parties to establish and/or strengthen, where appropriate, institutional, administrative,

and legislative arrangements for the development of integrated management of marine and

coastal ecosystems, plans and strategies for marine and coastal areas, and their integration within

national development plans. According to that decision, crucial components of IMCAM are

relevant sectoral activities, such as construction and mining in coastal areas, mariculture,

tourism, recreation, fishing practices and land-based activities, including watershed management,

all of which are relevant to NACOMA’s intervention area.

33.

NACOMA will also provide a framework to address some of the key United Nations

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and objectives of the New Partnership for Africa’s

Development (NEPAD) and the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD,

Johannesburg 2002). MDG No. 7 promotes integration of the principles of sustainable

development into country policies to reverse the loss of environmental resources. Similarly, the

NEPAD framework, which emphasized the pressing duty to eradicate poverty and to place

African countries, both collectively and individually, on a path of sustainable growth and

development, places great importance on the inclusion of environmental issues. The NEPAD

Environment Initiative further targets priority interventions such as coastal management for

protection and utilization of resources to optimal effect, environmental governance for securing

institutional, legal, planning, training and capacity-building requirements, and a structured and

fair financing system for sustainable socio-economic development. Other major elements of

NEPAD are good governance and decentralization, which are seen as the root of sustainable

development. The WSSD’s goals of Water and Sanitation, Energy, Health, Agriculture and

Biodiversity (WEHAB) identify institutional, technical, juridical and capacity-related obstacles

for biodiversity and sustainable ecosystem management and, thus, promote the integration of

biodiversity concerns and values into overall sustainable development strategies and plans, as

well as the management of biodiversity in a socio-economic context. NACOMA will address and

respond to these important objectives by mainstreaming coastal zone conservation and

management into Namibia’s development policies, building institutional capacity, and promoting

decentralized regional planning of the Namib coast.

B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION

34.

The Project takes into account national and international lessons learned from

biodiversity conservation under ICZM approaches, which demonstrate the need to go beyond

pure conservation measures. It uses two main avenues for enhancing coastal biodiversity

16

conservation and sustainable use: (i) Targeted investments on the ground and other direct

activities leading to improved coastal and marine biodiversity conservation; and (ii)

Mainstreaming biodiversity conservation and sustainable use principles into development

planning, sectoral policies, national, regional and local decision-making processes, and capacitybuilding measures linked to the production landscape. NACOMA’s intervention area will stretch

over the entire Namibian coastal ecosystem (including defined marine ecosystems) and will thus

enhance the integrity of coastal and marine ecosystems (see map in Annex 17 and description of

Project intervention area in Annex 4).

1. Financial modality

35.

NACOMA will be funded through a GEF grant of $4.9 million, over a period of 5 years.

2. Project development (and global) objective

36.

The Project development (and global) objective is: Conservation, sustainable use and

mainstreaming of biodiversity in coastal and marine ecosystems in Namibia strengthened.12

Outcome indicators

37.

i. X km2 and number of terrestrial and marine13 biodiversity hotspots under effective

management as defined by NAMETT14 by year 5 compared with baseline situation.

ii. Flow of economic benefits from activities linked to ecosystem and biodiversity

management on the coast has increased by year 5 compared with baseline situation.

iii. Biodiversity related aspects are incorporated into all up-coming sector policies

(tourism, fisheries, mining and urban development) at national, regional and local levels,

as identified in the White Paper, by year 5.

3. Project components

The global objective builds directly on Strategic Objective 6 of the Namibian NBSAP, which is to ‘Strengthen the

implementation of the Constitution of Namibia (Article 95L) by adopting measures to improve the protection of

coastal and marine ecosystems, biological diversity and essential ecological processes, and to improve knowledge,

awareness, and the sustainability of resource use’.”

13

In the project context, marine hotspots are meant to be MPAs: MPAs are here defined based on IUCN’s definition

(Resolution 17.38 of the IUCN General Assembly, 1988, reaffirmed in Resolution 19.46, 1994): “Any area of

intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural

features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed

environment.”

14

“Effective management” would be assessed through use of the Namibian adapted WWF/WB PA tracking tool

(NAMETT), a score card for PAs and MPAs.

12

17

38.

As a result of the Project, targeted enabling conditions for biodiversity conservation and

sustainable use, in particular those related to mainstreaming into coastal management and

development planning at the national, regional and local levels, will be improved, and a strategic

approach will be put in place to address root causes of biodiversity loss and coastal degradation

(see section B, Annex 3 and 4). The environmental and economic potential of the coast will

consequently be sustained, and the Project would thus provide local, regional, national,

international (in particular benefits to its riparian coastal states, Angola and South Africa) and

global benefits.

39.

Below is a summary of the four interlinked components and sub-components of the

NACOMA Project (see Annex 4 for a detailed Project description):

Component 1: Policy, Legal and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Ecosystem

Management of the Namib Coast (GEF US$: 0.91 million)

Sector issue addressed and expected outcomes

40.

The objective of this component is to mainstream biodiversity conservation and

management into policy, legal and institutional structures affecting the sustainable development

of the coastal zone of Namibia. Existing national, regional, local and sectoral frameworks,

including Vision 2030, NDP 2, RDPs, NBSAP and NAPCOD, all call for sustainable

development of the coastal zone. Through a review of current laws and support for appropriate

amendments, this component will help in the development of modern, harmonized

environmental legislation and coastal zone policy, while its efforts to clarify institutional

mandates will contribute to the decentralization process and the establishment of a clear

institutional framework for ICZM. The production of a formal White Paper detailing the

rationale for a national coastal policy and setting out objectives and strategies for implementation

based on the principles of biodiversity conservation and integrated coastal zone management15

will contribute toward a common vision for Namibia’s coast. The Namibia Coastal Management

White Paper will provide an overarching and comprehensive framework to support integrated

planning and decision-making related to coastal lands and waters, based on the carrying capacity

of the Namibian coast as a whole. It will be based on a highly participatory approach involving

the identified stakeholder groups in multiple consultations and meetings (see Annex 20 for an

outline of the project participation plan).

Primary target group

41.

National (mainly MET, MFMR, MME, MAWRD, MWTC, MRGLH), regional and local

governments involved in CZM.

Sub-components (see Annex 4 for a detailed description)

I.1. Review of Existing Laws and Support for Appropriate Legislation

42.

Existing legislation, from which respective ordinances derive mandates to set regulations

for coastal zone management, result in an overlap in the jurisdictional areas of different relevant

15

According to the CBD definition of IMCAM.

18

line ministries, such as MET, MME, MFMR and MAWRD. This sub-component will support a

review of and appropriate amendments to these acts and enhance their harmonization consistent

with principles of ICZM and with results from sub-component I.2 (clear definition of

jurisdictional areas for these line ministries). Importantly, this sub-component will provide the

MET with targeted support and technical assistance in establishing the scope and process of

measures related to National Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), which is a critical

instrument to enable and support ICZM and mainstreaming of biodiversity.

I.2. Clarification of Institutional Mandates

43.

This sub-component will provide institutional and, to a certain extent, legal input to

support a shift from nationalized to regional and local management of biodiversity and coastal

resources through their mainstreaming into the ongoing decentralization process. The

clarification of institutional mandates will be particularly relevant for the ICZMC, which could

potentially be the lead structure to facilitate mainstreaming of coastal biodiversity conservation

management and sustainable use into sectoral policies and actions. 16

I.3. Development of Policy Framework

44.

Based on sub-components I.1 and I.2, this key sub-component supports the development

of a highly participatory national coastal vision and ICZM policy framework, the Coastal

Management White Paper, to guide national, regional and local planning and management

processes in terms of principles, objectives and substantive content relating to coastal resource

conservation, development planning, socio-economic issues and enforcement. Emphasis will be

placed on providing access to benefits from coastal resources for local communities (including

tourism activities and other economically beneficial developments such as aquaculture and

fisheries), while enforcing the protection of areas of national and global interest, including

wetlands and fragile watersheds. It will facilitate the GRN’s commitment to ICZM by providing

basic principles and components to integrate into future NDPs and associated RDPs, consistent

with the goals of Vision 2030. This sub-component includes the organization of a series of

broad-based stakeholder consultations and facilitator workshops (see Annex 17). An outline of

the proposed approach (principles, methodologies, scope and content) of the White Paper has

been developed and will be attached to the PIM.

I.4. Development of Coastal Profiles

45.

Through the participatory development of regional coastal profiles, this sub-component

will further bridge the knowledge gap about socio-economic, environmental and biodiversity

conservation and development issues and their inter-related linkages. These profiles will in turn

be used as a basis mainly for local and regional, as well as national, decision-making processes

relevant for mainstreaming biodiversity conservation and will feed back into the State of

Environment Report and National Resource Accounting efforts. The profiles will be published,

reviewed, endorsed and up-dated on a regular basis by the Regional Councils.

16

A key lesson learned from the closed Erongo Region ICZM Project is that without institutionalized coordination,

fragmentation occurs. Therefore, institutional arrangements need to be supported that are sustainable and survive

any Project arrangements (e.g. ICZMC).

19

Specific outcomes

46.

(i) Policy and legal framework relevant to coastal zone management clarified and,

following a prioritization process, harmonized.

(ii) Roles and mandates of line ministries, RCs and LAs clarified with regard to

conservation and sustainable use of coastal biodiversity, and definitions in place for

coastal zone planning and management.

(iii) A collaborative vision for the conservation and sustainable use of the Namib coast

developed and used as a basis for a draft comprehensive coastal zone policy framework,

the Namibia Coastal Management Green Paper and a first draft White Paper.

(iv) Regional coastal information available and used regularly in local and regional

decision-making processes.

(v) Increased budget allocations for ICZM-related issues by relevant line ministries,

including from improved capture of the rent linked to the resource base.

Component 2: Targeted Capacity-Building for Coastal Zone Management and Biodiversity

Conservation (GEF US$: 1.52 million)

Sector issue addressed and expected outcomes

47.

Capacity-building has been identified as one of the main bottlenecks for sustainable

development in Namibia (see Vision 2030, NDP 2 mid-term review and National Capacity Self

Assessment (NCSA) reports). Moreover, it is widely recognized that the lack of capacity at the

national, regional and local levels for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use, including its

mainstreaming, stems from (i) a shortage of qualified staff and restricted budget for additional

positions; (ii) limited resources and time for training activities; (iii) uncoordinated sectoral

efforts; (iv) the slow decentralization process; (v) limited understanding of coastal biodiversity

and linkages to development planning and management; and, finally, (vi) weak and fragmented

communication channels between the various stakeholders.

48.

This component will fill the capacity gap at the local, regional and national levels in

support of ICZM, biodiversity conservation and sustainable use, including mainstreaming of

coastal biodiversity and resources into development planning and key economic activities. By

providing training for ICZM and developing M&E and knowledge management systems, the

component will contribute to the ongoing decentralization process as well as the development of

an effective institutional framework for ICZM.

Primary target group

49.

Local, regional and national government (MME, MET, MFMR, MRGLH, MWTC,

MAWRD), ICZMC members, RDCs involved in CZM.

Sub-components (see Annex 4 for detailed description)

II.1. Training for ICZM

50.

Based on the results from sub-components I.1 and I.2. and the available training needs

assessment for regional, local and national government (mainly MET), this sub-component will

20

partner with other initiatives to provide cost-effective training to the identified stakeholder

groups (ICZMC, RCs, LA, line ministries). Identified capacity-building measures cutting across

components 1, 2 and 3 relate to

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM - planning and management including

management plans);

Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA);

GIS and mapping;

Monitoring and Evaluation;

Participatory approaches (communities, private sector, government); and

Communication and negotiation skills.

These measures will be provided through (i) technical assistance through the Environmental

Advisors (see component 4), and national and international thematic experts, (ii) thematic

training workshops, (iii) on-the-job training, and (iv) study tours.

51.

Finally, this sub-component will provide targeted support to MET’s efforts to mainstream

and decentralize biodiversity management by specifically strengthening local and regional

delivery mechanisms.

II.2. Biodiversity Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanism

52.

This sub-component will involve the review of existing biodiversity M&E systems, and

assessment of coastal and marine biodiversity data and information gaps and needs. Further, it

will support the development or upgrading of a cost-effective, accessible and sustainable method

for a long-term coastal and marine biodiversity M&E system linked to other national

environmental monitoring efforts and the coastal profiles.

II.3. Coastal Biodiversity Knowledge Management

53.

This sub-component has two sub-objectives: One is to develop a knowledge management

mechanism (network), led by ICZMC, to allow stakeholders to share information (e.g. on

management plans, interventions, mainstreaming opportunities, meetings, training), including

feedback loops for inter-sectoral, vertical and international sharing of lessons and best practices

related to ICZM and mainstreaming coastal biodiversity management into development

planning. The other is to create an action-oriented communication strategy that will increase

environmental awareness among all key target groups and facilitate ownership and full public

participation in the Coastal Vision and White Paper development process.

Specific outcomes

54.

(i) Capacity and resources of RCs, LAs, MET, MME, MAWRD, MFMR and MWTC are

strengthened to undertake functional and strategic coast-relevant planning and decisionmaking process conducive to biodiversity conservation and mainstreaming thereof into

RDPs, NDPs and investment decisions (e.g. by RDCCs).

(ii) The ICZMC has been strengthened and is fully operational.

(iii) Knowledge related to coastal biodiversity and sustainable use is enhanced, including

mainstreaming into development planning and coastal zone management through

improved communication channels at local, regional and national level.

21

(iv) Awareness of the importance of coastal zone resources and ICZM among

stakeholders and local communities is enhanced.

Component 3: Targeted Investments in Critical Ecosystems for Biodiversity Conservation,

Sustainable Use and Mainstreaming (GEF: US$ 1.52 million)

Sector issue addressed and expected outcomes

55.

NACOMA has been designed to seek a balance between support for enabling

environments (e.g. management plans) for investments in established and new conservation

areas, and mainstreaming efforts in coastal and marine production landscapes through the

participatory approach supported by the ICZMC and at the regional level by the RDCC. These

activities will make use of the regional coastal profiles and existing national, regional and local

development and biodiversity priorities (e.g. RDPs, NBSAP) and their implementation.

56.

This component will contribute to the overall framework for ICZM along the Namib

coast by using targeted investments and activities to address on-the-ground gaps in coastal

biodiversity conservation and sustainable use throughout the Namib coastal and marine

ecosystems rooted in under- and un-protected biodiversity hotspots. These activities will be

complemented by MET’s NPA Project, which addresses management and sustainability issues in

targeted national terrestrial parks. 17

57.

The Project, through this component, will focus on a combination of coastal and marine

biodiversity priority sites (see Annex 18 and 17) including:

i. Terrestrial coastline hotspots that are currently under-protected or un-protected,

including Ramsar sites and other wetlands of biodiversity value that lack tools for

management; and

ii. Marine protected areas (though none currently exist, they are urgently needed) and

other unprotected islands and near-shore sites.

Primary target group

58.

Local, regional and national government (mainly MET, MAWRD, MFMR, MME,

MWTC) involved in CZM, local communities and the private sector in and around biodiversity

hotspots.

Sub-components (see Annex 4 for detailed description)

III.1. Coastal and Marine Biodiversity Management Plans

59.

This sub-component includes a participatory review, update and development of

management plans for key biodiversity priority conservation sites and their buffer zones (e.g.

Skeleton coastlines, Ramsar sites, future MPA sites), in line with recommendations on the

appropriate financial and institutional mechanisms and capacity development needs emerging

17

NACOMA will look at the coastal-related inter-sectoral links and integration of planning efforts at national,

regional and local scales, while the UNDP/GEF supported NPA Project will focus on PA-specific management and

operational plans.

22

from Components 1 and 2. Further, this sub-component aims to support the creation of new

protected areas (e.g. three Marine Protected Areas and Walvis Bay Nature Reserve); in order to

increase functioning biodiversity conservation management in priority coastal areas, demarcation

and gazetting of these sites will be supported.

III.2. Implementation of Priority Actions under the Management Plans

60.

This sub-component will support implementation of reviewed and updated or new

management plans through targeted investments related both to biodiversity conservation and

rehabilitation, as well as sustainable use activities linking biodiversity conservation with

economic development and benefits for the local coastal communities in and outside identified

hotspots. It prioritizes sustainable use activities with high potential for piloting, testing and

learning (replicability). Targeted and site-specific investments that are eligible for funding under

the NACOMA Project ( providing global environmental benefits in addition to local ones) have

been identified during preparation. Potential biodiversity conservation activities as outlined in

existing management plans are: GIS surveys and mapping, species-specific conservation

measures (e.g. for Damara tern, flamingos and lichen fields), control and regulation measures

(e.g. sports fishing, quad biking), soil erosion control and vegetation cover rehabilitation.

Potential investments related to sustainable use include income-generating activities that are

connected to ecosystem services, such as guiding facilities, ecotourism (desert hikes, campsites),

rehabilitation of existing tourism facilities such as desert paths, viewing sites and sign posts,

sustainable fish farming, etc. This sub-component would further provide support for limited

infrastructure and equipment for site management purposes.

Specific outcomes

61.

(i) Strengthened and mainstreamed network of costal and marine conservation areas with

defined and improved management plans under implementation.

(ii) Enhanced biodiversity status in critical ecosystems of Namibia’s coastal and marine

area.

(iii) Co-management of conservation areas (including buffer zones) consistent with

conservation and sustainable uses objectives.

Component 4: Project Management and Performance Monitoring (GEF US$: 0.95 million)

Sector issue addressed and expected outcomes

62.

This component reflects the incremental need for an operational project coordination

structure. The Project, through this component, will support the establishment and

operationalization (through staffing, office infrastructure and Project management-related

capacity building) of a slim Project Management Unit (PMU) housed in the Erongo Regional

Council. The Erongo Regional Council hosts currently the ICZMC Secretariat as well as the

NACOMA preparation coordinator.

Primary target group

63.

Project Management Unit staff.

23

Sub-components (see Annex 4 for detailed description)

IV.1. Project Office and Management

64.

This sub-component will support the recruitment of three long-term staff, a NACOMA

Coordinator and two Environmental Advisors. Additional PMU support staff for administration,

financial management and procurement and monitoring will be contracted or outsourced on a

part-time basis.

IV.2. Project Reporting and Information

65.

This sub-component will include performance and impact monitoring, evaluation of

Project progress and M&E reporting, all responsibilities of the PMU (see Annex 6).

Specific outcomes

66.

(i) Successful Project implementation according to Project Implementation Manual,

EMP and annual work plans.

Successful implementation of NACOMA’s four components as described above will lead to

global benefits in the form of enhanced biodiversity conservation (at habitat, species and

ecosystem levels) and sustainable resource use in the terrestrial and marine coastal ecosystems of

Namibia (see intervention zone definition in Annex 4), as well as enhanced environmental

management and planning, mainly at local, regional and national levels.

4. Lessons learned and reflected in the Project design

67.

The Project has been designed based on experience and lessons learned related to coastal

zone management and biodiversity conservation. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), poverty remains

one of the biggest threats to successful conservation and management of coastal biodiversity. A

general pattern has emerged of rapidly growing coastal cities and settlements with rising

unemployment rates that put increased pressures on the integrity of coastal ecosystems. Although

policy frameworks addressing coastal management have already been established by a number of

African states, development of institutional and legal frameworks to support implementation of

these policies has not yet been targeted in most countries around Africa’s coastline. The Project

has carefully taken into account experiences within the region and adapted strategic directions

provided in the “Integrated Coastal Management in SSA: Lessons Learned and Strategic

Directions”18:

68.

(i) Lack of enabling legal and regulatory frameworks, together with significant

constraints in human resource skills and institutional capacity, have resulted in limited

sustainability of operations targeting conservation and sustainable use of coastal biodiversity in

SSA. Long-term effects have further been curtailed by ad-hoc approaches with narrow sectoral

focus. Overlapping issues, jurisdictions and impacts of integrated coastal management require

adequate institutions to guarantee the necessary interagency coordination and interaction.

18

Indumathie Hewawasam, Integrated Coastal Management in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons Learned and Strategic

Directions, 2001.

24

69.

NACOMA will address these critical needs by i) supporting development of policy, legal

and regulatory frameworks in Component 1; ii) promoting capacity building, in particular for

integrated coastal zone planning, management and monitoring for the Regional Councils, Line

Ministries and Local Authorities, in Component 2; (iii) providing funds for urgently needed

targeted investments to maintain key biodiversity values in priority sites in Component 3; and

(iv) strengthening the ICZMC to become a sustainable coastal zone entity.

70.

(ii) Conservation operations targeting coastal resources in SSA have often been limited in

scope, funding and commitment. Particularly in light of scarce financing options, partnership

building and networking has proven to be significant in promoting conservation operations.

71.

The NACOMA Project addresses this issue by encompassing the entire coast. In addition,

the Project has been developed in close coordination with the BCLME Programme to

complement sub-regional objectives with coastal priorities and activities, as well as with the

Finnish and French support projects to advance the decentralization process and the UNDP

support for national protected areas.

72.

(iii) Transparency in decision-making and public participation in program design have

been critical for project success in SSA.

73.

Throughout the Project preparation process, NACOMA has sought to facilitate ownership

and initiative by national, regional and local stakeholders through the ICZMC, public

consultations and information dissemination. Further, NACOMA has been cooperating with the

follow-up initiative of the pilot DLIST, which has been used actively by Project stakeholders

during the preparation process as an information platform for sharing ideas, experiences and

documents. Future approaches to foster communication, coordination and learning by using

DLIST services and others are now under discussion. A detailed Project Participation Plan is

being developed as part of the Project preparation phase and will be closely linked to the

communication strategy under Component 2 (see Annex 20).

74.

(iv) Availability of scientific data and information on which to base policy frameworks

and management plans has been a major challenge for most ICZM projects in SSA.

75.

The Project will support the establishment of a national coastal zone scientific group in

which the main national research institutions are expected to participate. The main hosts of

scientific coastal and marine data are currently the BCLME and BENEFIT (Benguela

Environment Fisheries Interaction and Training) programmes. The results of ongoing scientific

assessments, in particular those related to the status of the coastal and marine ecosystems and

biodiversity and impacts of offshore and on-shore mining and fisheries, will be made available to

NACOMA and the proposed scientific group. The Project also plans to support the development

of a joint database and coastal monitoring mechanisms. Other information, such as coastal data

for the Erongo Region19 various land use plans and the COFAD report20 on potential MPAs on

19

From a previous pilot study funded by the Danish Agency for Cooperation and Development (DANCED).

Advisory Assistance to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Baseline Study of the Establishment of

Marine Reserves in Namibia – Short Term Consultancy Report, 1998.

20

25

the Namibian coastline, will be collected and made accessible to all stakeholders, and used to

update the coastal profiles under Component 1.

76.

In summary, the following key ICZM supportive elements and success criteria have

been identified and integrated into the NACOMA Project design:

Involvement, commitment and ownership of national and local authorities;

Emphasis on the integration of economic, social and environmental issues (i.e. not

isolating the environmental agenda);

Movement away from small-scattered projects;

Ensured financial sustainability;

Adequate understanding of local socio-economic, ecological and cultural factors and

efforts to bridge the knowledge gaps on these issues;

Existence of inter-sectoral coordination through a mechanism, backed by high-level

political authority, to bring together stakeholders on a continuing basis; and

Targeted human and institutional training and capacity building based on innovative

approaches to instill ecosystem and multi-sector processes.

Lessons from similar projects in Namibia (see also Annex 2)

77.

(i) The objective of the DANCED-financed pilot Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Project in the Erongo Region (1997-2000) was to achieve and maintain long-term sustainable

economic and ecological development of the coastal zone through establishment of baseline data

for resource management and fostering of the decentralization process within the Erongo Region.

Its main driving force was to address environmental protection of the coast as an ecosystem,

rather than focusing only on animal protection and fishing of protected species, as previous

conservation efforts in Namibia had done. The project succeeded in bringing together

stakeholders to pool ideas, knowledge and experiences to develop a draft vision for regional

coastal management. One outcome was the creation of the Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Committee (ICZMC) in 1990. The project was also instrumental in raising awareness about the

need to share information among the coastal regions. However, by the end of the project,

inadequate integration of planning and resource management still prevailed, a situation that was

seen as being partly caused by the lack of high-level support for the ICZMC as well as the fact

that the decentralization process did not reach a stage where delegation of powers was actually

transferred. Therefore, the final evaluation report recommended that any potential follow-up

support would require clear operational structures of RCs.

78.

NACOMA design: The Project builds on the positive and critical lessons learned from

the DANCED-supported ICZM Project, which identified mainly the slow decentralization

progress and the resulting shortage of qualified staff for environmental planning in the Regional

Council as a key barrier for achieving Project objectives. NACOMA timeliness is demonstrated

by the fact that (i) most planning positions in Regional Councils are being filled and

organizational structures are being clarified, (ii) decentralization is progressing with some line

ministries (e.g. MAWRD) ready to launch an actual process over the coming months, (iii) RCs

are in the process of designating a responsible person as regional Coastal Zone Focal Point

(CZFP), and (iv) other complementary initiatives provide capacity-building to RCs and

26

MRLGH. Further, lessons learned have been used to design flexible and adaptable Project

implementation arrangements, a strong inter-sectoral Steering Committee with representatives