In the marketplace within the gray walls of Rouen, Normandy, on

advertisement

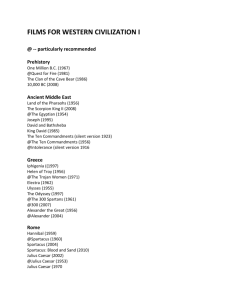

JOAN OF ARC AND THE SIEGE OF ORLÉANS by Don O’Reilly Military History (April 1998) In the marketplace within the gray walls of Rouen, Normandy, on May 30, 1431, in the shadows of the cathedral and guild shops, a harsh spectacle held the attention of the populace. A 19-year-old peasant girl was to be burned at the stake. A sign declared her ‘Jehanne, called la Pucelle, liar, pernicious, seducer of the people, diviner, superstitious, blasphemer of God, presumptuous, misbelieving the faith of Jesus Christ, braggart, idolater, cruel, dissolute, invoker of devils, apostate, schismatic and heretic.’ To many in the crowd, however, she was the innocent would-be rescuer of France from a century of English invaders. Unwittingly, the English were bestowing upon her a martyrdom that would haunt them for the rest of their numbered days on French soil. However surprisingly successful her gallant but brief career in war had been, Joan would be far more dangerous to England after her death, transforming a century-long clash of avaricious and vacillating feuding lords into a holy war for national liberation. The Hundred Years’ War raged amid what was arguably the worst century in the history of Western civilization. In France, crop failures, civil wars, invasion, horrendous epidemics and marauding mercenary armies turned to banditry reduced the population by two-thirds. The war began in earnest in 1346, when Edward III, King of England, invaded Brittany and marched on Paris. At Crécy, his army of 10,000 utterly routed twice their number of Frenchmen as English longbowmen annihilated squadrons of heavily armed French knights. In 1348 the bubonic plague, the Black Death, devastated Western Europe, killing millions within 24 hours of infection. In England, a third of the population perished. The plague ravaged crowded, polluted castles and towns more than it did isolated villages. The Roman Catholic Church decreed that anyone confronted with persons sneezing or coughing, symptoms of the disease, should bless them and quickly decide to either flee or stay to assist. The best of the clergy stayed—and many died. While papal decree condemned the idea that the source of the illness was Jews poisoning well water, common folk killed them anyway, as well as blaming other scapegoats—witches, heretics and, if one was French, ‘les goddams Anglais’ (a nickname referring to the English tendency to use profanity more readily than did the French). Heavily taxed in order to pay the English ransom for their king and lords captured at Poitiers in 1356, the already oppressed French peasantry erupted into a revolt, known as the Jacquerie. The rebels torched castles, churches and towns. Meanwhile, unpaid foreign soldiers of fortune spread their own waves of terror as they pillaged the land. Because they slaughtered farmers’ cattle, the English soldiers earned another nickname— ‘boeuf-manges,’ or ‘beef-eaters.’ In 1378, the struggle wracked the church with rival claimants to the papacy at Avignon and Rome, the former backed by France and the latter by England. Religious and political authority alike were in confusion. By 1415, England’s young King Henry V had demanded the crown of France and then had offered to settle for less, an offer few trusted. Henry V then invaded France, in violation of a previously signed treaty, and seized the port of Harfleur. His army reduced 1 by disease, he retreated toward Calais. Attacked en route by the French at Agincourt, Henry’s archers again annihilated the French knights, inflicting 7,000 casualties to England’s 500. The English occupied all northwestern France, from the Atlantic to the Loire River, including Paris. When Henry V visited one of his prisoners, the Duke of Orléans, in the Tower of London, he told him, ‘You deserve to lose.’ The Frenchman agreed, as did a great many of his countrymen. Continued defeat and economic deterioration had left France in a state of passive denial that bordered upon political and military despair. The most powerful duchy in France at the time was that of Burgundy, occupying most of the eastern region. When the dauphin, son of the mentally ill King Charles VI, had met with John of Burgundy to plan an alliance against the English, the dauphin rashly accused the Burgundian of treason because of his earlier inaction against the invaders. One of the dauphin’s entourage then stabbed and killed the duke. That treacherous act only drove the Burgundians to ally with England. The dauphin, a brooding, irresolute man like his father, was reluctant to act any further; his attempt at diplomacy had failed, and his military strategy was threatened by the new enemy alliance. Besides, he was afraid of horses. France was reduced to the area south of the Loire, then called Armagnac. On August 31, 1422, Henry V died of dysentery—depriving the English of their most charismatic leader of the war—and John, the Duke of Bedford, became regent for the 7month-old King Henry VI. On October 22, Charles VI also died. None of his relatives appeared at his funeral, but the Duke of Bedford did. No sooner was the king’s tomb closed than Bedford proclaimed his infant ward ‘Henry, by the Grace of God, King of England and of France.’ Although the dauphin made a counterclaim to the French throne, he was paralyzed by his unwillingness to assert real leadership and his jealousy of any noble who did. Soon all France north of the Loire River was controlled by the English or Burgundians except for a few holdouts: Mont St. Michel, Tornai, Vaucouleurs in Lorraine, and Orléans. What remained of France was saved by the Loire River. The English could not cross it without first reducing all French strongholds on its low, sandy shores. By autumn of 1428, the siege of the Loire citadel of Orléans had begun. The English fortified the southern access to the city’s bridge, ignoring the need to complete their siege lines on the northern side of the river around the walled town. Of all nations, France was first to give rise to a popular image apart from the king. In the 1300s, folk literature and ballads spoke of Mre France—Mother France, beloved, merciful and long-suffering. But that was hardly preparation for the extraordinary resurgence in morale that would be set in motion by a teenage girl. Lorraine, watered by the Meuse flowing to the Rhine in northeastern France, remained loyal to the dauphin though separated from his sovereignty by some 200 miles of Burgundian territory. The garrison at Vaucouleurs defended the region. The Burgundians, preoccupied in the southwest, had left Lorraine relatively undisturbed by war. Its Ardennes hills and forest were of minor value, but they provided an advantage to its defenders. In the village of Domrémy, in Lorraine, lived the d’Arc family, who owned a farm and sheep pasture, but they were not serfs to the local lord, Robert de Baudricourt. Their home boasted a glass window. There were five children, two boys and three girls. One of the girls, Jeanette—known in English as Joan—was born on January 6, 1412. 2 At the age of 13, this illiterate shepherdess and ‘excellent seamstress’ first heard the voices that would address her throughout her life. Usually they were preceded, she said, by a great light. She claimed they were the voices of Saints Margaret and Catherine, queens of France, and Archangel Michael, commander of the heavenly host. They convinced her to swear to remain a virgin ‘as long as it shall please God.’ When Joan was about 17, the voices told her to leave Domrémy without her father’s knowledge and rescue Orléans. They promised nothing more. In many respects, though, she seemed a rather ordinary girl—the tomboy next door, the always-adoring younger sister one had to defend, the neighborhood girl never unfriendly but preoccupied, whose glance one sought to catch. She was called by the French la Pucelle—literally, the virgin. The English would call her ‘the Maid’ on rare occasions when they spoke of her courteously. The title ‘Jeanne d’Arc’ would not be used in reference to her until the 16th century. Her call to ‘Follow me,’ even when headed into certain danger, would be heeded willingly by men who would not have followed a grizzled veteran on such occasions. Approaching her uncle, an ex-sergeant named Durand Laxhart, as her voices directed her, she told him that he should bring her to the commander of Vaucouleurs, de Baudricourt. She must have expected that her uncle, whose war stories she had heard, would aid her. How much she explained to him is unclear, but she was taken to de Baudricourt and told him of the voices she had not dared to mention to her parents. She asked for horses and an escort to go across Burgundian territory to aid the dauphin, whom she wished to see crowned king of France. Although she told de Baudricourt that her voices had assured her that he would aid her, the flabbergasted commander at first told Joan to go home. She did so, narrowly escaping an unsuccessful Burgundian raid on the walled town. When she returned to Vaucouleurs toward the end of Lent in 1429, de Baudricourt changed his mind and granted her wish. Perhaps he reasoned that the rewards would be great if she was somehow successful, but her loss would be of small concern. Dressed in male attire—because, as she would explain, she feared rape—the Maid, accompanied by a knight, his squire and her two brothers, crossed Burgundy. Traveling on horseback only at night, in 11 days they arrived at Chinon, the dauphin’s residence, in February 1429. The dauphin had already received a letter dictated by Joan. Questioned, she replied, ‘Have you not heard that France would be lost by a woman and restored by a virgin from the Lorraine borderlands?’ The woman who had lost France was generally considered to be Isabeau of Bavaria, the dauphin’s mother, whose discouraging lack of faith in France and the men of her family, and whose readiness to accept English demands, had made her quite unpopular. The dauphin refused to see Joan immediately, but had her quizzed for almost a month by officials and churchmen. Impatient and eager to get to Orléans, she gave terse, practical and intelligent answers—albeit in uneducated fashion. Once she was accepted by her interviewers, she was sent to the dauphin, who, changing clothes with one of his officials and hiding in a crowd, waited to see if the Maid would be aware of the trick. She immediately walked directly to him, respectful but annoyed at such games. Perceval de Boulainvilliers, a knight who would be in Joan’s company, described her: ‘This maid has a certain elegance. She has a virile bearing, speaks little, shows an admirable prudence in all her words. She has a pretty woman’s voice, eats little, drinks very little wine. She enjoys riding a horse and takes pleasure in fine arms, greatly likes 3 the company of noble fighting men, detests numerous assemblies and meetings, readily sheds copious tears, has a cheerful face. She bears the weight and burden of armor incredibly well to such a point that she has remained fully armed during six days and nights.’ The testimony of well over 600 people who knew her would be recorded in court. Not even in the trial, which was rigged illegally by her prosecutors, would any witness speak a word against her. Yet we have no description of her facial features, nor do we know the color of her hair. Outfitted in a suit of white enameled armor specially made for her, and carrying a banner of white and blue with two angels and the single word ‘Jesus,’ she proceeded with a gathering army from Chinon to Tours, to Blois and then to Orléans. On the way, she ordered the clergy at Saint Catherine’s Church in Ferbois to dig under the stone floor near the altar to find a sword. She had never visited the town, but a sword was produced, somewhat rusty, its origins a mystery. She would never use it in battle, but carried it nevertheless. La Pucelle startled many witnesses by using the flat of the sword to beat a prostitute following the army, one of a host of such professionals driven out of the camp. Even the most puritanical chaplain would not have dared to take the same actions. Furthermore, she forbade swearing. To the astonishment of their officers, soldiers accepted her strictures with little complaint. If she was sent by the saints, it was natural that she would make such demands, the soldiers reasoned, hoping against all cynicism that she was genuine. If she could not save Orléans, the English would cross the Loire and, in all probability, conquer France. The key to the siege was the wood-and-stone bridge over the Loire between the town and the towers, Les Tourelles, on the south shore. For four hours on Thursday, October 21, 1428, the English had attacked a rampart of earth and stakes guarding the approach to Les Tourelles, losing 240 men. Townswomen hauled buckets of boiling water, fat, lime and ashes to the defenders, who then poured them down on the English scaling ladders. On October 23, the French abandoned the rampart, which had been undermined by English tunneling. The next day, the English took Les Tourelles, undefended and ruined by cannon shot. Thomas Montague, Earl of Salisbury, inspected the site and was mortally injured by a French cannon on October 24. He was succeeded as commander by the Earl of Suffolk, who in turn was replaced in December by the more aggressive John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. Talbot arrived with 300 reinforcements and heavier cannons. He based his army west of the city. The French also received reinforcements led by John Dunois, comte de Longueville (the ‘Bastard of Orléans,’ son of the imprisoned duke) and the Gascon mercenary Etienne de Vignoles, better known as La Hire. On Christmas Day 1428, a truce was honored from 9 a.m. until 3 p.m. The English requested that the French musicians in Orléans play for them, and they did. Supplies in the town were dwindling—on January 3, 1429, a covey of 154 pigs and 400 sheep entered Orléans through the eastern gate, evidence of the laxity of English patrols. The French sortied against the English camp at St. Laurent on an isle near the town on January 15, but the alerted foe threw them back into the river’s shallow waters. On February 12, a crucial fight occurred. The English, with 1,500 men, including French allies from Picardy and Normandy, and a convoy of 300 carts loaded with barrels 4 of salted herring for Lent, were attacked by a sortie in strength from Orléans. Having been warned, the English circled their carts into a defensive laager. The French and their Scottish mercenaries, surprised by that maneuver, could not agree upon their next move. Their orders were to fight on horseback and not dismount, thus ensuring a quick withdrawal to Orléans. Sir John Stewart, the Constable of Scotland, disobeying that command, ordering 400 men to attack the wagon ring on foot. The French stayed on their mounts at a distance, uncooperative, at which point the English, led by Sir John Fastolf, charged out of their defensive circle and sent the Scots reeling in retreat until 60 to 80 mounted men from the French main body, led by the Count of Clermont, charged the scattered English. In the process of aiding the Scots, Clermont was unhorsed, hit in the foot by an arrow and narrowly escaped being killed or captured before two of his archers placed him on another mount. Sir John Stewart was killed. The Battle of the Herrings, as it came to be called, was the last sortie the French would make until Joan’s arrival. Even as the siege tightened, however, a break for the French emerged on the political front. The town council of Orléans had appealed to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, to aid his fellow Frenchmen diplomatically. In response, Philip asked Bedford to remove the English forces before Orléans and leave it a neutralized city under Burgundian control, adding that he would be ‘very angered to have beaten the bushes that others take the bird.’ Bedford refused. The Burgundian troops in his command thereupon left the siege. The first formal news of the Maid’s arrival among the English was a letter from her to their commander, asking them to leave Orléans and France. In it she was titled the French chef de guerre. This was undoubtedly a clerk’s entry. Joan was illiterate and not the French chief of staff, although she did have a ‘battle,’ as it was called in the era—a battalion of several hundred men. The English ignored the letter, but they were alerted to the approach of the new French force. The only free access to Orléans was by its eastern Burgundy Gate. The English camp of St. Loup was on the western side of the town. The English held the towers on the south shore of the Loire, and the French the gates of Orléans at its other end. The wooden bridge itself was a no man’s land in easy range of missiles from either side. The French were wary of reinforcing the town. A major effort required a fleet of riverboats and rafts poled or sailing against the strong current of the river in spring flood. The winds were weak and against the river armada, but Joan, as always, remained positive and eager to proceed. Abruptly, the winds became stronger and changed direction, speeding the boats upstream past English archers and cannoneers, few of whom fired a shot. The contrary wind shortened the range, weakened the impact and handicapped the accuracy of arrows. The cannons of the era were inaccurate against a moving target. To distract the English, a sortie was made from Orléans against St. Loup, with heavy casualties on both sides. The river fleet passed St. Loup and disembarked most of its passengers and cargo on the south shore as the Maid landed on the north, entering Orléans unopposed by its eastern gate. It was April 29, 1429, and Orléans held a celebration and a parade. At 8 p.m., Dunois and many nobles who had met the relief expedition outside the walls entered the Burgundy Gate amid torches, banners and a cavalcade of armored men surrounding la Pucelle in her white armor. 5 Joan soon discovered that the Orléanists, while happy to see her, were reluctant to launch a major attack against their besiegers. The day following her arrival, she and the English commander shouted to one another from opposite ends of the bridge. Talbot declared her a whore and the French captains pimps, warning that if he captured the ‘cowgirl,’ she would be burned at the stake. On Sunday, May 1, a truce was observed. Dunois, the Bastard of Orléans, sortied and brought back reinforcements from Blois. The English offered no opposition, knowing that they would soon be reinforced by freebooters led by Sir John Fastolf. Although the Frenchmen were alarmed at that information, the Maid was elated, saying jokingly that if they failed to tell her when Fastolf was near, she would chop off the head of the Bastard of Orléans. Joan had been napping when she suddenly arose and announced that her ‘counsel’ told her to attack immediately. But she didn’t know whether the assault was supposed to be against the English defenses or against Fastolf’s approaching column. She galloped out the eastern gate and joined a French assault that was already in progress westward against St. Loup. The French were taking many casualties, and Joan was saddened at the sight of the wounded stumbling back to the town. She raced on as the French cheered and rallied, storming St. Loup. The nearby English bastions, alarmed by the size and fury of the French attack, made no move to intervene. All English defenders within St. Loup were killed, whereas the French lost only two men. The aftermath was revealing. The Maid burst into tears at the sight of the English dead. When an English prisoner was struck with a sword by one of his guards, she held the captive’s head as he died. She declared that all the French should thank God for victory and confess their sins, or she would leave them. All prostitutes were to leave the army. The next day, the Feast of the Ascension, she would make no war. Within five days, she announced, the English would withdraw—then she sent her foes her third and last decree. The note was wrapped about an arrow shot across the bridge into Les Tourelles. It included a request that her herald, seized by the English, should be exchanged for a prisoner of the French. The English reply was shouted insults against the ‘Armagnac whore.’ Joan wept, as she often did when involved in angry confrontations. Joan asked that the gate toward Les Augustins—the English-held, fortified monastery on the south shore—be opened for a sortie, but the captain in charge of it refused, fearing an English attack through the open gate. La Pucelle demanded the doors be unlocked, and many soldiers and civilians agreed with her. The captain finally relented. Since the English had built a barrier spanning the bridge’s width, the Maid led a sortie across a shallow inlet of the Loire to the island of Aux Toiles southeast of the town’s walls. From there, using two boats as a floating bridge, the French landed on the south shore and attacked and seized the fort of St. Jean le Blanc, whose English defenders fled to the larger and stronger Les Augustins, near Les Tourelles. There, resistance was so formidable that the weary French withdrew. St. Jean le Blanc was subsequently abandoned by both sides. Arriving by boat with La Hire and other mounted knights, Joan quickly saw that the English in Les Augustins were about to sortie against the retiring French. Lowering her lance, she led a charge that rallied the French, who now pressed hard upon the English as 6 they attempted to re-enter Les Augustins by an open gate. Fighting their way into the fortress, the French pushed on until their banners replaced England’s on its walls, and the English fell back to Les Tourelles. All night, the civilians in Orléans brought food and supplies across the river. The French captains told the Maid that they should not attack immediately, but inform the dauphin of their progress thus far and then await his decision. She scorned their advice, knowing that her soldiers were eager and the dauphin habitually indecisive. She ordered an early sortie, stating that her ‘counsel’ had warned her that she would be wounded that day above her breast. From morning to night on May 6, the French assaulted Les Tourelles, held by the English commander Talbot. Soon after joining the attack, Joan was struck in the shoulder by an arrow, just as she had predicted, and wept as she was carried from the field while English archers jubilantly shouted, ‘The witch is dead!’ Angrily refusing magic amulets offered by men-at-arms, she had her wound—which turned out to be no more than a flesh wound, the arrow having barely penetrated her armor—treated with olive oil and lard. She confessed to her priest in a highly emotional state. Since it was late in the day and the troops were exhausted, Dunois was about to call off the attack when Joan returned from Orléans on horseback. She had removed herself for some 10 minutes to pray, then returned, carrying her banner. The English, who had just sortied outside the walls of Les Tourelles, rushed back inside, shaken by the unexpected French resurgence. Although he expected a French retreat amid the confusion and lack of prompt communications in the battle, a French knight, Jean d’Aulon, courageously resolved to advance against the next English sortie on May 7. Joan’s standard-bearer, exhausted, had handed her banner to a soldier known as le Basque. D’Aulon asked le Basque to join him. Together, they went into the moat and struggled to climb out of it to the timber walkway of the bridge. Joan demanded that le Basque give her back the banner—she gripped the end of the cloth, but le Basque, at d’Aulon’s insistence, refused to part with it. Instead, he raised it. The French men-at-arms, seeing the banner advancing to the edge of the bridge, rushed to it and stormed the bridge, Joan climbing the first scaling ladder raised. Four hundred to five hundred English attempted to flee Les Tourelles, but the bridge, meanwhile, had been set afire and it collapsed. Most of the English were killed or drowned. The French who had hoped to take their foes captive for ransom were shocked and dismayed. The Maid wept and shrieked at the English deaths. On the following day, Talbot lifted the siege and the French re-entered Orléans by the bridge gate. That day, all the English south of the Loire were captured or killed. The next day, a Sunday, as the town celebrated a Te Deum of thanksgiving, the English forces north of the river demolished their camps and withdrew. Joan’s men were ready to attack the retreating column, but she forbade it, saying that on a Sunday they should fight only in self-defense. The column was harassed the next day, and cannons and other weapons were seized. The dauphin sent news of the victory to all French towns friendly to him, scarcely mentioning the Maid. Bedford wrote the king, explaining that the English had lost ‘by the hand of God as it seems,’ because of la Pucelle, ‘a fiend with enchantments and sorcery.’ Clearly, the leaders on both sides used Joan for their own purposes. The Maid’s victory at Orléans had a snowball effect as volunteers gathered to the 7 fleur-de-lis banners. Marching onward, the French took Jargeau on June 20, 1429, killing 1,200 English after their offer to parley went unheard amid the melee. The town of Meung surrendered. At Beaugency, the English retreated under an agreement of safe conduct. The Constable Arthur de Richemont, a Breton on the outs with King Charles, brought his 1,000-man battle to join Joan’s army. Other French had refused him alliance and even threatened him, considering him self-serving. ‘Joan, I have been told you want to fight me,’ Richemont said to her. ‘I do not know if you are from God or not. If you are from God I fear nothing from you, for God knows my goodwill. If you are the Devil, I fear you even less.’ She replied, ‘Ah, handsome constable, you are not come for my sake but because you are come you will be welcome.’ The English, under Talbot, were approaching Meung, joined by Fastolf’s 1,000 mercenaries. On June 18, the opposing armies formed up in a pageant of arms. The French nobility asked Joan what to do. ‘Have all good spurs,’ she answered. Uncertain, her listeners asked if she meant they should flee. ‘Rather the opposite,’ she answered, predicting an English rout. Charging with a force of 6,000, including 1,000 mounted knights, the French inflicted 4,000 casualties on their foes. At Patay, the French pursued an English convoy. At a narrow pass through hedges and woods, the English set up an ambush of 500 archers and awaited their own rear guard. French scouts unwittingly flushed a stag from the forest, which raced through the English lines, prompting shouts that the scouts overheard and alerting them to the English ambush. As the English rear guard retreated on the run, the main English force, with Fastolf riding ahead to summon the vanguard to their aid, wrongly presumed there had been a rout and panicked as the French charged pell-mell. By the time Joan arrived, the English had lost some 2,000 men, the French only three. Talbot was unhorsed and captured, but Fastolf had escaped. Joan returned to Orléans to urge that Dauphin Charles be crowned at Reims, the traditional scene for such ceremonies. The town was in Burgundian hands. With a cavalcade of nobles and infantry, the dauphin journeyed to Reims. En route, they approached Troyes, held by a Burgundian garrison of 600. Letters sent to the town promised that all would be forgiven if the dauphin was welcomed. The town sent a friar to sprinkle the Maid with holy water. ‘Approach boldly, I shall not fly away,’ she told him. With her army on the edge of starvation from campaigning in the ravaged countryside, she commenced a siege, assuring her men that within three days they would take the town ‘by love or by force or by courage. ’ Upon seeing the French ready for an assault at dawn, the town yielded. At Reims, Joan had no artillery or siege equipment, but advised, ‘advance boldly and fear nothing.’ The city yielded without a fight, and on July 16, 1429, the dauphin was officially crowned Charles VII, king of France. Joan knelt before the king and said that she had accomplished what God had ordered of her. The only favor she asked was that her village of Domrémy be exempt from taxes. Visited by her brothers, she told them she was homesick. She wished to return home ‘and serve my father and mother by keeping sheep with my sister and brothers who will rejoice so greatly to see me again.’ It was never to be. The king allowed the Burgundians a two-week truce prior to further negotiations, the Burgundians agreeing to yield in Paris. Their agreement was insincere, however, as they 8 were stalling for time to reinforce Paris with a newly landed force from England. Joan was shut out of the negotiations. The French monarch was thinking only in diplomatic terms and ignoring the military situation. Joan no longer heard her voices, but she decided to attack Paris nonetheless. With a force of 12,000, she led an assault on the Porte Ste.-Honoré on September 8, but was hit in the leg by a crossbow bolt. Her standard-bearer, hit in the foot, opened his helmet visor to remove the arrow and was shot between the eyes. The wounded Maid was carried away by her comrades in arms, still insisting that the attack continue. The king undermined Joan’s efforts. He withdrew from Paris to Glen, and on September 21 disbanded his army. Joan resumed campaigning in early 1430, though her force was reduced to little more than her own battle. She was aware that she was losing her grip on events. At Chinon, she remarked that her voices had warned her, ‘I shall last a year, hardly longer.’ A siege of Charité-sur-Loire ended in impasse—Joan’s audacity was no longer compensation enough for her inadequate forces. Later, during her trial, Joan claimed that upon the moat in a successful assault at Melun, her saints had warned her that she would be captured before St. John’s Day, the summer solstice. Philip the Good of Burgundy, who had taken on much of the burden of fighting for the English, dispatched his vassal, John of Luxembourg, to seize the town of Compiègne. On May 13, 1430, however, Joan moved first and entered Compiègne by surprise. In the early morning of May 23, she sallied against the Burgundians outside the town. Unaware that an English unit had moved between the town and her attacking force, she pressed on. The French within the town closed its gates, keeping out both friend and foe. Joan, fighting wildly, was pulled from the saddle by a Burgundian soldier. Her brother, Pierre, was also captured, and some 400 of her men were killed. The Burgundians sold the Maid to the English for 10,000 gold coins. Tried as a heretic and witch in a procedure flagrantly violating the legal process of the era, she was offered women’s clothes in prison and then raped. Thereafter, male attire was the only clothing allowed her. Her male attire was then taken as ‘proof’ that she refused a church command that she dress as a woman, and in spite of the weakness of all other evidence against her, she was burned at the stake by the English at Rouen on May 30, 1431. Of the 42 lawyers at her trial, 39 had asked for leniency and an appeal to a higher church court not under the thumb of the English. Of scores of witnesses who claimed to know her personally, not one maligned her—and those witnesses were chosen by the prosecution, the Maid being denied a defense council. Was la Pucelle neurologically handicapped, part of a royal plot, a fantasist, crazy, a saint or a con artist? Her trial revealed her to be uncommonly bright, forthright, courageous, without bitterness, yet aware that she had been abandoned by the king whom she had saved. Nevertheless, she had saved her nation, with an innate charisma matching that of England’s King Henry V. And in 1920, Joan of Arc was recognized as saint by the Roman Catholic Church. Every year on May 8 at Orléans, a pageant re-enacts Joan’s entry into the city, today a prosperous and attractive blend of old and new architecture. On the plaza her memory is commemorated in the statue known to American troops stationed there after World War II as ‘Joanie on the Pony.’ 9