Legal Reasoning and Coherence in Law

advertisement

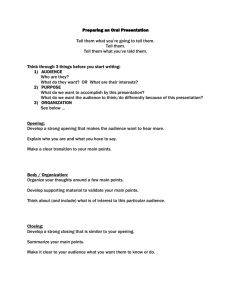

1 Lecture Notes on Legal Methods (30/10/03) - Is there such a thing as legal science? Does legal science transcend national legal systems? SECTION ONE: Legal Methods 1) Rules of Statutory Interpretation: 1. The Literal Rule 2. The Golden Rule 3. The Mischief Rule 4. The Purposive Approach 5. Integrated 2) The Doctrine of Precedent or Stare Decisis 1. 2. 1. 2. 3. Ratio decidendi and obiter dictum Definition of ratio decidendi: “Any rule of law expressly or impliedly treated by the judge as a necessary step in reaching his conclusion.” Binding precedents The following constitute binding precedents: The ratio of a decision of a court in a previous case is binding on lower courts in the same court hierarchy. Some courts are bound by their own previous rationes. Persuasive precedents There can be said to be three kinds of persuasive precedents: The ratio of the decision of a lower court [or sometimes the same court] in the same court hierarchy. The ratio of the decision of any court in another court hierarchy. Obiter dicta. 3) Coherence According to Ken Kress the coherence theories of law have a special claim on us: “The idea that law is a seamless web, that it is holistic, that precedents have a gravitational force throughout the law, that argument by analogy has an especial significance in law, and the principle that all are equal under the law, provide strong prima facie support for a coherence theory of law”. 4) What is the Relationship between Legal Method and Coherence? SECTION TWO: Previous discussions on the nature of scientific knowledge See Geoffrey Samuel, Epistemology and Method in Law (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2002) - The focus of legal method is narrowly judge orientated, but most practising lawyers and legal scholars readily admit that much of law in practice is never brought before a court or gets near a judge. - What is law: is it the law on the books or the law in action? - What is law: from whose point of view are we to consider the law - The German legal scientist views the law as a system of principles and axioms. Legal knowledge is for such a jurist a matter of concise propositions systematically arranged in an abstract world of concepts. - Oliver Wendall Holmes: If we take the view of our friend the bad man we shall find that he does not care two straws for the axioms or deductions (from principles or ethics), but that he does want to know what the Massachusetts or English Courts are likely to do. - Equally the knowledge structure of a policeman and the prison officials will probably be different from that of the judges - The point to be stressed here is that there is no single idea of what it is to have legal knowledge. - Much depends on what William Twining called standpoint or point of view in an observational sense. SECTION THREE: Law as A Participant Oriented Discipline Excerpt from the introductory chapter to Reza Banakar, Merging Law and Sociology (Berlin/Wisconsin, Galda + Wilch, 2003). 2 …Law is “a participant-oriented discipline” and as such tends to give priority to definitions and approaches which are based on “practical insider attitudes”. 1 The inside/outside distinction also became useful in that it helped to counteract the tendency in legal studies to present one participant standpoint, such as the standpoint of the appellate judges or Law Lords, as the only legally relevant and valid perspective on law and to neglect a variety of other standpoints, such as those of the plaintiffs, legal advisors, jurors and prosecutors. The distinction also impresses on the outside observers, such as social scientists analysing law and legal behaviour, that the law and its effects on society cannot be sufficiently grasped and analysed without taking into account the practical insider attitudes which mould its internal mechanisms. My understanding of what was at stake gradually changed due to the realisation that notions of “insider” and “outsider” did not represent unchangeable social factors and were, in fact, subject to variations in different cases. Despite the fact that the operations of the legal system hinge on law’s ability to sharply distinguish between the legal and the extra-legal, the inside and outside of law could not be conceptualised in immutable and absolute terms, for the simple reason that the boundaries of the law were constantly in flux and its content was a matter of endless negotiations. The inside and outside of law were, instead, variables indicating two relative forms of experience, i.e. experience-near and experience-distant manifestations and perceptions of the law. These experiences were, in turn, shaped by the social context, which defined the “inside” and the “outside” of the law in relation to those people and circumstances that reproduced the law and its institutions at any given time and place. An individual (such as a policeman or an academic lawyer) or an organisation (such as the police or the law faculty) could be “insider” in one relationship and, at the same time, “outsider” in another relationship or social context. An arresting officer could be regarded as an insider to the law from the point of view of a detainee, but as an outsider from the point of view of the prosecutor, the defending attorney or the magistrate. A solicitor can be regarded as an insider when advising his or her clients, but as an outsider in the Inns of Court. The usefulness of making a sharp distinction between the perspectives of insiders and outsiders can be further questioned from an action theoretical perspective and by bringing into consideration the notions of “observation” and “participation”. 2 To put it differently, on the basis of the specific standpoint adopted by various actors in respect to law and the degree to which they participate in legal processes, we can describe a variety of distinct approaches to, and experiences of, law and legal institutions. For example, some social actors, such as journalists reporting on a trial proceeding, observe the law from the outside without being involved in its processes (they can be called “outside observers”). Others, such as judges or barristers participate in its reproduction (they are “inside participants”). Another group, such as solicitors advising clients or briefing barristers observe the law from within, without engaging in legal processes themselves (they become “inside observers”). Yet another group consists of outsiders, such as plaintiffs or lay judges, who temporarily participate in legal processes (they are “outside participants”). The diversity of standpoints on law in relation to the actor’s degree of “participation” in legal processes cuts across the simple distinction between the inside and outside of law. The notions of inside and outside of law are not obsolete, but they are not absolute either. They simply vary from case to case and from time to time, which means that they become sociologically meaningful and useful in relation to specific social contexts and times. In this sense, by distinguishing the legal from the extra-legal and, thus, momentarily defining the inside and the outside of the law, a temporary time/space (legal) grid is imposed on social reality. Also, the law’s contextual imposition of a grid helps us to understand how the law manifests itself simultaneously at various levels of social reality. This is one of the valuable ideas developed by Georges Gurvitch and presented in relation to more recent empirical research in Part Two. Although the original focus on the distinctive differences between how lawyers (defined as “inside participants”) and sociologists (understood as “outside observers”) view the law was useful in describing and examining the interdisciplinary tensions permeating socio-legal research and scholarship, and also highlighted the difficulties connected with integrating sociological and legal forms of knowledge, it otherwise analytically and empirically restricted the investigation into the interdisciplinary challenges of the sociology of law. This turning point is presented in Chapter Five, where the development of the sociology of law is compared with 1 William Twining, Globalisation and Legal Theory (London, Butterworths, 2000) at 129. Twining is here referring to H. L. A. Hart, The Concept of Law (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1988) at 88-91. Also see the notion of “the bad man” in O. W. Holmes, “The Path of Law” in (1897) 10 Harvard Law Review 457. “The bad man”, who might be an ordinary citizen, a lawyer advising a client or a sociologist studying the law, “does not care two straws for the axioms or deductions” and instead is only interested in what “the courts are likely to do in fact” (Holmes, ibid., at 457). In this way, Holmes draws attention to the significance of the external standpoints in respect to law and legal decisionmaking. At the same time “the bad man” highlights the limitations of a concept of law which is exclusively based on the internal standpoints, such as those entertained by some judges, legal scholars and other high priests of the institutions of law. For a critique of external theories see Ronald Dworkin, Law’s Empire (London, Fontana, 1991) at 14. 2 See Twining, above at 129. 3 that of the sociology of medicine and lessons are taken from the sociology of religions concerning the insider/outsider dichotomy…. Participation Insider’s Perspective Outsider’s Perspective Observation 1. Inside Participant - Judges Barristers 2. Inside Observer - Legal Advisors - Legal Scholars 3. Outside Participant - Juries - Plaintiffs 4. Outside Observer - journalists - sociologist SECTION FOUR: The Feminist Method Anne Bottomely: “By drawing on other disciplines we are now asking if not only the practice of law silences women’s aspirations and needs, and conversely privileges those of men, but whether the very construction not only of legal discourse, but representations of discourse in the academy (the construction of our understanding and knowledge of law) is the product of patriarchal relations at the root of our society”. Law achieves this in three ways: 1) Boundary definitions: It is a process thereby certain matters are identified as outside the realm of law, i.e. certain matters are identified as political or moral rather than legal. 2) Defining relevance: For example the student of law learns that it is “relevant” in cases of rape to know the victims’ sexual history. 3) Case analysis: Some cases become good law even though there is a vast choice. It is not necessarily logic that lead judges to the right decision. Cases are decided in a post hoc fashion. See Carol Smart, Feminism and the Power of Law (London, Routledge, 1995): - Law sets itself above other forms of knowledge by claiming to have the method to establish the truth (which is taught at law schools. - A more public version of this method is found at criminal trials, where judges and juries can come to correct legal decisions. - The fact that other judges in the higher courts may overrule some decisions only goes to prove that the system ultimately divines the correct view. - Law’s claim to truth is not manifested so much in its practice, but rather in its ideal. - However, law extends itself beyond uttering the truth of law, to making such claims about other areas of social life: “No matter how you may dispute and argue, you cannot alter the fact that women are quite different from men. The principal task in the life of women is to bear and rear children:… He is physically stronger and she the weaker. He is temperamentally the more aggressive. It is he who takes the initiative and she who responds. These diversities of function and temprament lead to different outlook which cannot be ignored. But they are, none of them, any reason for putting women under the subjugation of men” (Lord Denning 1980: 194) - The judge is held to be a man of wisdom, a man of knowledge, not a mere technician who can ply his trade. - Here Denning is articulating a truth about the natural differences between women and men. - He combines the Truth claimed by socio-biology (i.e. a “scientific” truth) with the Truth claimed by law. He means that there is no point for disagreement… - In this sense the feminist position is reconstructed as a form of “disqualified knowledge”, whilst the naturalistic stance on inner gender differences acquires the status of legal truth. Law’s “Truth” Excerpt from the introductory chapter to Reza Banakar, Merging Law and Sociology (Berlin/Wisconsin, Galda + Wilch, 2003). … In her study of rape, Carol Smart reveals some important aspects of law’s internal mechanism for producing images of society, in general, and gender relations, in particular. Smart argues that the legal 4 method, which is epistemologically based on the application of a number of binary opposites such as guilt/innocence, lie/truth, culture/nature, man/woman and rationality/emotionality, is formed in such a way as to disqualify knowledge derived through other methods.3 In criminal trials of rape, it operates through the binary logic of truth/untruth, guilt/innocence and consent/non-consent as a rigid system of exclusion, including only what is deemed relevant in legal terms, which may be irrelevant to the question of rape as far as women are concerned. The rape trials hinges on whether consent or non-consent can be established. In practice it would seem that consent is assumed and the raped woman must prove non-consent…[T]he consent/non-consent dyad is irrelevant to women’s experience of sex. Neither begins to approach the complexity of women’s position when she is being sexually propositioned or abused. This is not to say that women themselves do not know whether they want a sexual encounter or not, but the “telling” of a story of rape or abuse inevitably reveals ambiguities. Hence a woman may agree to a certain amount of intimacy, but not to sexual intercourse. There is also no room for the concept of submission in the dichotomy of consent/non-consent which dominates the rape trial. Yet submission may be what the majority of raped and sexually abused women have endured. In other words, in fear of future violence or in fear of losing a job, women may submit unwillingly to sex. Yet in legal terms submission fits on the consent side of the dichotomy. Having submitted, but failing to meet the legal criterion of non-consent, women are deemed to have consented to their violation. The only alternative when non-consent is not established is to presume consent—and hence the innocence of the accused.4 Law sets itself outside the social order and above all other forms of knowledge using its legal method and rigour to reflect upon the world from which it is divorced. 5 It exercises its authority through its “claim to truth”, writes Smart, and consistently fails to understand the accounts of rape which do not conform to the narrowly constructed legal definitions (or Truth) of rape. Law has its own understanding of women, sexuality and rape, which is internally produced and revealed in decisions and opinions of judges and courts and the discourses of legal scholars. For example, time and again we come across statements by judges that women are liable to be untruthful and when they say no do not always mean no.6 This also reveals the maleness of the law and the fact that its methods are used to realise this maleness internally. 3 Carol Smart, Feminism and the Power of Law (London, Routledge, 1995). 4 Smart, ibid., at 33-34. 5 Smart ibid., at 11. 6 Smart ibid., at 35.