Why Open Source Software / Free Software (OSS/FS, FLOSS, or

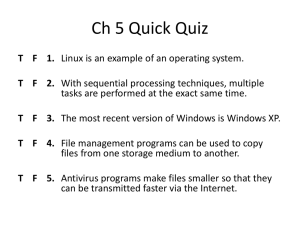

advertisement