The Road - National Coalition for Child Protection Reform

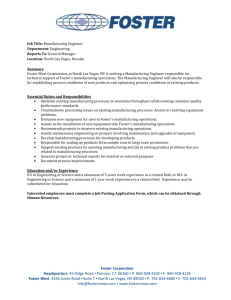

advertisement