In “The Question of Research in Ecocomposition,” Speaker 7

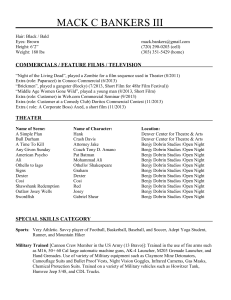

advertisement

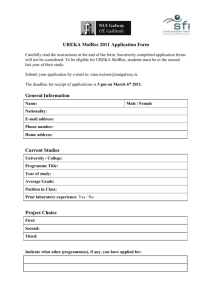

The Question of Research in Ecocomposition David M. Grant, University of Wisconsin – Madison CCCC-ASLE SIG March 24, 2006 Chicago, Illinois One thing often taken as a mark of a field’s growth or maturity is the state of its research. In the early 1970s, composition is said to have matured with the psychological research agenda inspired in the wake of Janet Emig’s (1971) The composing processes of twelfth graders, even though other markers such as annual conferences and professional venues of publication already existed. While ecocomposition’s terminology can be traced back to Richard Coe’s (1975) “Ecologic for the composition classroom” and Marilyn Cooper’s (1986) “The ecology of writing,” it has only been since around the beginning of the millennium that a plethora of resources has emerged – from Derek Owens’ (2001) Composition and sustainability, to the two volumes on ecocomposition co-authored by Sid Dobrin and Christian Weisser (2001, 2002); from Margaret Syverson’s (1999) Ecology of composition to Nedra Reynolds’ (2004) Geographies of composition. However, as composition’s own history attests, a plethora of sources does not necessarily mean a field has taken root, as it were. Given the wide-ranging strands that currently compose ecocomposition, experts and novices alike are often confused over just what can be considered research in ecocomposition and what distinguishes it as a useful approach. Michael Cohen (2004) has argued that ecocriticism has, of late, suffered too much from its own pieties, neglected the “branching tree of ecocritical methods,” and, in an effort to be politically effective, muted the often contentious task of criticism. Given our proximity and even allegiance with ecocritics, we might well take his argument seriously. While there is no one research method appropriate to ecocomposition, we can look at research paradigms within ecocomposition’s history in order to locate promising methods for new studies and approaches. What has the past research been? What does it say? What methods have been used? What questions linger? What does ecocomposition study? How might our research help move ecocomposition forward to improve both student writing and the overall health of the planet? Which way is “forward,” anyway? Answering such questions can help us to articulate more clearly not only the findings of our research, but also our purposes and value to both the academy and the general public. As one potential line of thought, we might ask what research in ecocomposition is doing to define the boundaries of our field. Tim Taylor’s (2002) research on the history of ecocomposition notices “divergent strands,” which he labels environment as metaphor (EAM) and environment as subject (EAS) approaches. While the former often serves as a way to broadly theorize about language and the writing process, often from an ecocritical stance, the latter often serves to engage in intellectual activism and environmental literacy. These two need not be mutually exclusive as Dobrin and Weisser point out in Natural discourse (2002). However, Taylor opens the way to ask the question of what counts as “ecocomposition.” Where does a composition course turn into a survey on nature writing or ecocritical methods and how might the two be approached differently? Must research in ecocomposition blend language theory and intellectual activism, and if so, how? How is ecocomposition different from more traditional composition scholarship? Does ecocomposition imply ecocriticism and where do the two intersect? Related to this is the possibility of particular theories excluding one or another method. For instance, again Dobrin and Weisser (2002) explicitly critique “the social constructionist assessment of the role of the individual” (14) thus precluding any method that relies “too heavily upon collectivist, cumulative perspectives” (158). We may be tempted to read this as a 2 preclusion of statistical analyses or binaristic data sets often found in the social sciences. However, educational sociology is beginning to investigate classroom ecologies and sociology departments are reexamining their understanding of thinkers such as Marx for inspired analyses of how to respond to the environmental crisis. Nystrand, Gamoran, and Carbonaro (2000) and Nystrand and Graff (2001) offer social constructionist accounts of how cumulative interactions between people affect classroom ideology and can either create space for or foreclose specific kinds of discourse. Both of these latter accounts were conducted through software analyses of classroom discourse whereby a statistical correlation was shown between certain categories of discourse and student responses. While differing theoretical perspectives should be encouraged, are there any research methods especially favored by ecocomposition? Are there any methods that are simply not compatible given ecocomposition’s major theoretical planks? What methods do we use and why do we use them? I think we would all agree as geographer David Harvey (qtd. in Braun and Castree 1998) argues that “the interweavings of social and ecological projects in daily practices as well as in the realms of ideology, representations, esthetics, and the like are such as to make every social (including literary or artistic) project a project about nature, environment, and ecosystem, and vice versa” (189). However, Harvey leaves open the question of competing paradigms for understanding these projects; such paradigms might be broadly construed as objectivist, postpositivist, postmodern, and the like. Louise Phelps (1988) has attempted to articulate an ecology of composition as a human science, concomitantly arguing that all writers operate within ecological systems that are part of the “real” world, and that can be known and understood. But would a realistic paradigm, even one informed by post-Kuhnian science, preclude some aesthetic or emotional understandings? If not, how does ecocomposition research articulate certain agenda 3 within radical paradigms? How might particular theoretical frameworks account for both human subjectivity and empirical, rational understanding? Finally, the philosophy of language that coincided with sixties rebelliousness may have done much to liberate people from oppressive conditions and social spaces. However, those same insights are now used to support equally deadly conditions such as the War on Terror and the K Street Project, conditions that seem less transparent in their purposes. How do know our research affects these interweavings in a way that has positive effects on the planet? What goals do we see as most compelling given the state of the planet and recent predictions that we may have passed a point of no return in terms of ecological destruction? These are just some ways we might begin to grapple with question of research in ecocomposition. In doing so, we will likely revisit themes from past conferences, hopefully in new ways that speak to graduate students and experienced researchers alike. In doing so, I also hope we can better understand our pedagogical purposes, our allegiances, and spaces for further and continued scrutiny. Most importantly, these questions, and a discussion of them can help members of both CCCC and ASLE clearly respond to critics, articulate our shared sense of our own value, and maintain relevance in the eyes of colleagues, administrators, and students. 4 References Braun, B. and N. Castree. (1998). Remaking reality: Nature at the millennium. New York: Routledge. Coe, R. M. (1975). Eco-logic for the composition classroom. College Composition and Communication 26.3: 232-37. Cohen, M. (2004). Blues under the green: Ecocriticism under critique. Environmental History 9.1, 9 – 36. Cooper, M. (1986). The ecology of writing. College English 48: 364-75. Dobrin, S. and C. Weisser. (2001). Ecocomposition: Theoretical and pedagogical approaches. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. --- (2002). Natural discourse: Toward ecocomposition. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Emig, J. (1971). The writing processes of twelfth graders. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Fleckenstein, K. (2003). Embodies literacies: Imageword and a poetics of teaching. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Nystrand, Gamoran, and Carbonaro. (2000). On the ecology of classroom instruction: The case of writing in high school English and Social Studies.” Writing as a Learning Tool. 1-31. Nystrand, M. and N. Graff. (2001). Report in argument’s clothing: An ecological perspective on writing instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 101, 479-493. Owens, D. (2001). Composition and sustainability: Teaching for a threatened generation. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. Phelps, L.W. (1988). Composition as a human science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reynolds, N. (2004). Geographies of writing: Places and encountering difference. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Roorda, R. (2001). Great divides: Rhetorics of literacy and orality. In S. Dobrin and C. Weisser, Eds. Ecocomposition: Theoretical and pedagogical approaches. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Taylor, T. (2002). A historical understanding of ecocomposition: The greening of university rhetoric. Ph.D. Diss., University of Alabama. 5