Vietnam War - eduBuzz.org

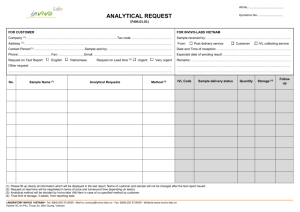

advertisement

"Incomplete and Profoundly Confused": A Bibliographic Essay on the Vietnam War by Mary Wilson November 1995 Not surprisingly for such a controversial era, the body of literature surrounding the Vietnam War is immense, nearly overwhelming for the novice. The bibliography in the third edition of one of the standard texts, George Herring’s America and Vietnam, for example, encompasses nineteen pages. The literature includes numerous first-hand reports by American journalists, statesmen, military leaders, and soldiers, and more recently, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese participants. The breadth is wide, including a seeming plethora of military, cultural, political, media, and anti-war movement analyses. Perhaps all that remains to be done, as post-war tensions between Vietnam and the United States subside, is a more complete, multi-dimensional history as documents from the "enemy" are opened to historians. Steps taken recently to establish diplomatic relations between the two countries are a harbinger that such a study may be a reality before long. Until then, Americans will continue to study "this side" of the war, incomplete as it is. This paper will summarize trends in the historiography of the war and then analyze in more depth some of the most important works representative of those trends. Diplomatic historian Warren Kimball, in a 1974 review article of three Cold War histories, described the development of the historiography of wars. First appear the "white paper" histories written during or soon after an event by those most closely involved in policy-making, obviously reflecting their views and supportive of official policy. These are then disputed by critical, partisan, and often conspiracy-minded revisionists. Next, defenses of official policy, more scholarly in tone and incorporating some revisionist arguments, begin to emerge. More scholarly revisionists then appear, and finally, after time heals at least some of the emotions, an "eclectic synthesis" appears, combining arguments and conclusions from all sides. The pattern is not rigid, Kimball wrote, citing external events that shape intellectual attitudes (1119-1120). Certainly, one of the "external events" that shaped perspectives of Vietnam War history was the Cold War. Of the several historiographical essays that deal with the Vietnam War, two are extensive and offer an excellent analysis of Vietnam War scholarship. One by Robert Divine appeared in Diplomatic History in 1988 and the other by Gary Hess appeared in the same publication in 1994. Writing fourteen years after Warren Kimball, Divine explains that while one would think that the initial analysis of the war would be supportive of American policy, the opposite is true. The orthodox or consensus position in this war is an attack on it, rather than support of it (Divine 79-93). This position, Hess writes, dominated during the war and "saw the United States, driven by a mindless anticommunism and with disregard for Vietnamese politics and culture, being drawn into a conflict that it could not win" (240). Kimball’s pattern was reversed. What caused the change? Certainly, it is difficult to consider the struggle in Vietnam apart from the Cold War. David Levy states that the debate over Vietnam began "when a carefully constructed ideology, a set of ideas that had guided and justified American foreign policy for more than a generation, began to fragment" (xiv). This set of ideas, prevalent from 1935-1965, was dominated by two strains: first, that the United States had a moral duty to defend ideals such as freedom and democracy, and second, that Americans had interests overseas vital to national security. In the late 1940s and 1950s these strains were linked to a fear of communism, considered to be an immoral ideology that, with its avowed intention of world domination, threatened American interests. These, Levy contends, were the grounds upon which the intervention in Southeast Asia rested (19, 38). The escalation of American involvement in Vietnam in 1965 shattered the consensus as it embroiled the United States in a war that did not fit Levy’s two strains very well. First, South Vietnam was only marginally identifiable with freedom and democracy, and many considered the manner in which the United States was waging the war to be immoral. Second, its tangible value to American national security was difficult to identify (Levy 53, 74). By the time Arthur Schlesinger wrote The Bitter Heritage in 1966, the Cold War consensus of communism as the clear villain of history had been shattered. In effect, Cold War revisionism became Vietnam War orthodoxy. Divine divides the orthodox interpretation into three types. One he labels the liberal internationalist interpretation, typified by Arthur Schlesinger and later by David Halberstam. Schlesinger developed the quagmire theory, that American leaders had inadvertently and mistakenly led the country into war: the roots of the Vietnam crisis "lie not in the malevolence of men but in the obsolescence of ideas" (ix). Schlesinger detailed the step-by-step process of American involvement in a war that was not really in the American interest: In retrospect, Vietnam is a triumph of the politics of inadvertence. We have achieved our present entanglement, not after due and deliberate consideration, but through a series of small decisions. It is not only idle, but unfair to seek out guilty men. Each step in the deepening of American commitment was reasonably regarded at the time as the last that would be necessary. Yet, in retrospect, each step led only to the next, until we find ourselves entrapped today in that nightmare of American strategists, a land war in Asia-a war which no president . . . desired or intended. (47) Schlesinger believed the war to be a "tragedy without villains" and identified nationalism rather than communism as the most powerful passion of the time. Though he may designate no villains, he highlights the decisions made during the 1963-1965 period and juxtaposes John Kennedy’s refusal to accept the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s recommendations in major issues (after the Bay of Pigs debacle) with Lyndon Johnson’s acquiescence of decisions made by the "warrior class" (137). Other historians have understood the Kennedy presidency as the pivotal period in American involvement (Jeffrey Kimball 179). The second interpretation Divine identified is the stalemate theory, which holds that American presidents escalated even while knowing full well that their actions were not going to be successful. Driven by domestic politics and haunted by the loss of China in 1949, Democratic presidents in particular did not want the albatross of losing a war against communism hung around their necks, say advocates of this position such as Daniel Ellsberg (Devine 82). Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy all managed to take limited measures to save Vietnam; Lyndon Johnson, however, escalated and "got caught with the Old Maid"--a land war in Asia--in the stalemate game (Divine 83; Ellsberg 102-103). As Divine states, however, presidential advisors such as Ellsberg essentially absolve themselves of the blame for Vietnam when they shift guilt so completely to the presidents, as the stalemate proponents tend to do. The third interpretation, according to Divine, is that the containment policy itself, more so than the participants in the system, was fatally flawed. Gabriel Kolko, the most radical proponent of this interpretation, blamed the United States almost entirely for the war, citing its efforts to "merge its arms and politics to halt and reverse the emergence of states and social systems opposed to the international order Washington sought to establish" (547). Other historians, such as George Herring , while more balanced in their approach, see containment as the wrong system for the wrong time in the wrong place (Devine 350) The revisionist interpretation, which in Cold War historiographical terms one would think of as the left, anti-war position, developed in the late 1970s by conservatives and military analysts after the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 as a defense of the American policy (Herring "America and Vietnam" 350; Hess 240). The revisionists supporting of American intervention in Vietnam differ in their critiques of how that policy was carried out. Such early revisionists as Guenter Lewy and Norman Podhoretz emphasized the morality of defending South Vietnam. Lewy in particular concluded that the fate of the Indochinese since 1975 is evidence that the United States was morally justified in intervening. He does not necessarily believe that America could have won the war, however, given the weaknesses and performance of the South Vietnamese government and army (438-439). Gary Hess divides later revisionists into three categories: the Clausewitzians, the hearts and minders, and the legitimacists (241). The Clausewitzians, typified by military analyst Harry Summers, Jr., use Karl von Clausewitz’s On War as a reference point and blame civilian leaders for misunderstanding the type of war that needed to be waged in Vietnam. The military was essentially at a disadvantage from the outset since they were restricted by civilians from invading the North, which, Summers believes, was the aggressor; the war was not a revolutionary war ("Strategic Perception" 39). Had the United States fought a conventional war against the North rather than concentrating so much on the Viet Cong, the outcome might have been different. Summers also faults civilian leaders for not declaring war, citing the difficulties of fighting a war in "cold blood," rather than in the heat of passion with American public opinion firmly behind the war effort as other wars had been fought (On Strategy 37). The problem would have been, of course, convincing Americans that this war was vital to their national interests. It is one thing to stir up passions in the aftermath of a Pearl Harbor; it is another in the aftermath of a Gulf of Tonkin "incident." "Hearts and minders" typically argue that pacification, not search and destroy, should have been the predominant military strategy. In their eyes, the army leadership deserves blame for fighting conventional warfare in a situation that called for, literally winning the hearts and minds of the peasants. Search and destroy missions--with the emphasis on destroying the country to save it--did just the opposite. One proponent of this theory, Andrew Krepinevich, Jr., believes that "the Army focused on the technological and logistical dimensions of strategy while ignoring the political and social dimensions that formed the foundation of counterinsurgency warfare" (233). In effect, the army was still fighting World War II and the Korean War. The legitimacists, Hess says, emphasize that America had a legitimate role in the area for national security reasons, and that the South Vietnamese government of Diem, particularly, deserved American support rather than a shabby overthrow. Historians of this persuasion, such as R. B. Smith, emphasize Chinese and Soviet interests in Southeast Asia, the evidence of economic growth during the Diem government, and the nationalism Diem evinced in refusing to concede to American advice (244-245). Even while revisionist histories were being written, what Hess calls neo-orthodox scholarship was developing, typified by historians, such as George Herring, who focused on the 1954-1968 period. These historians placed more emphasis on "flawed containment" arguments--that "a misreading of U.S. interests and Vietnamese realities led to a doomed effort to build an independent South Vietnam and ultimately to an unwinnable military intervention" (Hess, 246). Interestingly, in the third edition of America’s Longest War, Herring states that even with the vast changes in the world since his first edition appeared in 1979, he still holds to the flawed containment premise (xii). Whether the containment policy, primarily developed to combat communism in Europe, could be applied to a vastly different culture and geo-polititical setting is problematical, according to the neo-orthodox position (Anderson 425). Divine identifies two themes that appear in the most recent postrevisionist histories. First, historians such as Larry Berman, Kathleen Turner, and George Kahin are taking a new look at Lyndon Johnson’s role in the war and revising the previous estimation of him as a "thoughtless hawk who blundered into Vietnam" (Divine 90). Rather, he is now viewed more sympathetically as a person embroiled in a complex and difficult situation who chose not to choose between funding the Great Society programs and fighting the war. Second, recent historians have stressed American ignorance of the power and determination of Vietnamese nationalism, which made the war essentially unwinnable by the United States (Divine 92). Thomas Paterson, in a 1987 address to the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations, offers a different breakdown of interpretations, dividing them according to different lessons learned from the war that might guide future policy decisions. He identifies four categories: the "no more Vietnams" school, the "inevitability" school, the "diplomatic intervention" school, and the "win" or revisionist school (3-5). The "no more Vietnams" interpretation corresponds to those who think that American administrations should not intervene in Third World countries involved in a civil war. Do Americans, after all, really understand the problems of distant cultures and political structures? Adherents of this school, whose assumption is that the Vietnam war was a civil war, not an aggression on the south by the north, would have Americans stay out of insurgencies such as those seen in Central America and the Caribbean. The second school is more radical and believes that it is inevitable for the United States, because of her economic interests and need to be number one in the world, to intervene in future Vietnams. Those who hold a diplomatic intervention perspective understand the United States as a great power that must work for diplomatic, not military, solutions to the world’s problems, especially those that affect her interests where democratic governments are likely to succeed. Finally, the win interpretation, similar to the revisionists Gary Hess described, contends that Vietnam could have been won had the military been unrestrained by its civilian leadership. Much of Vietnam War historiography centers around the causes of American involvement. Jeffrey Kimball, finding the traditional historiographical terminology such as consensus or revisionist "obscure," has identified seven theories of causation (5) The first he calls the official theory, the American government’s public explanation of reasons for intervention as reflected in speeches, memoirs, and communications of policy makers. Each administration, Kimball writes, leaned toward their own favorite rationalizations for involvement: the Munich syndrome and machinations of international communist conspiracy (Truman); the domino theory (Eisenhower); dual threat of Chinese aggression and wars of national liberation (Kennedy); U.S. credibility and commitments to South Vietnam (Johnson and Nixon); Communist bloodbath (Nixon) (7). Actually, each successive administration used arguments of former administrations, but added their own flavor to the mix. Calling the official version the best-known theory, Kimball believes in many ways it is the most difficult one to study because it is impossible to know if policymakers really believed what they were saying or what they said and wrote was just rhetoric to sway public opinion. As Doris Kearns has said, memoirs must be read with an understanding of "the stage of life in which they were written, why they are being written at that time, and what audience they aim to please" ("Doris Kearns" 28). Kimball’s calls his second category of causation states of mind, abstract ideas, ideals and strategic concepts. By this he means such ideas and ideals as the containment doctrine and the cold-war vision of events, missionary idealism inherent in American foreign policy, and arrogance of power, all ideas that have been proposed by historians mentioned earlier in this paper. The third category of theorists concentrate on the process of involvement, seeing it as either a quagmire or a stalemate, theories discussed earlier in this paper. The role of the President concerns the fourth group of theorists, particularly the Presidents’ personalities and the emergence of the imperial presidency. Doris Kearns, for instance, described Lyndon Johnson’s self-admitted motivations for escalating the war: the communist threat, the fear of being called a coward, the fear of another Democrat losing a country to communism. The world view Johnson inherited combined with his personality to spell tragedy (Lyndon Johnson 252-253, 255). Similar to this is the fifth theory, that of the importance of the managers and bureaucrats, men such as the best and the brightest, and entities such as the Joint Chiefs of Staff. These theorists conclude that the highest government offices attract certain personality types--people with a drive for power, who need to assert machismo, who are tough, action-minded, who tend toward wishful thinking and practice groupthink (Jeffrey Kimball 16-17 ). In a similar vein, the fifth group has emphasized the importance of domestic politics and economics, as the stalemate proponents have. Other historians have emphasized a theory not already discussed in this paper, that of cultural misunderstandings and conflict. Francis FitzGerald’s Fire in the Lake is a prime example of an early book that concentrated on the differences between Vietnamese and American culture. When intervening in Vietnam, FitzGerald says, the United States was not only entering a "different epoch of history," it was also "entering a world qualitatively different from its own" (7). The basis for the Vietnamese villager’s culture was the land, which was his contact with his ancestors and essentially with his soul. Removing him from the land "exposed him directly to the political movement that could best provide him with a new identity" (10-11). That movement was the National Liberation Front, whose affiliation with the earth by way of intricate tunnels and underground storerooms paralleled the villagers’ (143-145). FitzGerald has been criticized for her romanticization of the NLF and her assumption that the mutual reliance of guerrilla and peasant would continue after the war and result in continued populism. Stephen Sestanovich noted in 1985 that the opposite had occurred following the South Vietnamese government’s demise in 1975; rather, Westernization of the cities tempered Communist orthodoxy (39, 41). Even so, FitzGerald’s book had a large impact on successive writers who came to see the war not only from the American side. Her focus on culture and the effects of the war on the Vietnamese added a new dimension that others subsequently adopted (Jeffrey Kimball 303). Warren Cohen theorizes that much of the historiography of the war focuses on one central question: was the war an act of aggression perpetrated by the North on the South or was it mainly a revolutionary war? It is an important question, Cohen believes, for it "determines much of the argument about the viability of the Saigon government, the legitimacy or realism of US intervention, the appropriateness of one or another military strategy, and why the Communists won" (108-109). Many revisionsts believe the war was an aggression of the North against the south and declare the war would have been winnable if the United States had engaged the North more fully and sealed off the borders more completely (Hess Vietnam and the United States 174). Cohen, however, argues forcefully that the idea there were two separate nations is fallacious. Similarly, Ben Kiernan writes that the debate between the two has been resolved: "The NLF was inextricably linked to Hanoi, but it comprised the southern branch of a nationwide Vietnamese movement" (1118-1119). Whither Vietnam War historiography? Robert Divine believes that historians will continue to move beyond the early simplistic concept of the United States as the wicked witch of the east and view the war more as a national tragedy (92 ). George Herring also observes that the debate between revisionists and consensus perspectives has moved away from the passions of early partisanship into earnest scholarship ("America and Vietnam" 350). Gary Hess foresees the opening of Vietnamese documents helping to "refine some of the contentions dividing the neo-orthodox and revisionist views," producing a more mature synthesis. He also believes that the Clauswitzian theory, with its emphasis on command, logistical, and bureaucratic problems will continue as part of military analyses; hearts and minders will continue to have an impact on the indictment of the military approach to the war; legitimacists will continue to emphasize the international aspects, though Hess thinks at least one aspect of this theory--the emphasis on the "better side" of the Diem government--will not have a long-lasting impact ("Unending Debate" 263-264). David Levy predicts that in time Americans will lose their sense of the uniqueness of the war, that they will see in the context of other wars America has fought. One outcome, he predicts, is that the debate will continue to illumine how people justify involvement in war (182-183). In 1986 Ronald Spector wrote that "Our knowledge of the Vietnam conflict is still incomplete and profoundly confused" (101) As I read many of the conflicting views and issues in a study of the War, one theme recurs: containment and the cold war. It may be said that the importance of the containment policy to the Vietnam War parallels the importance of slavery as a cause of the American Civil War. Several reasons can be posited for the war in 1865: weak leadership, states rights, economic differences between the North and South, slavery. Take slavery out of the picture, however, and none of the others would likely have been enough to cause the war. Take the Cold War and containment out of the Vietnam War picture, and other causes pale in significance. WORKS CONSULTED AND CITED Anderson, David L. "Why Vietnam? Postrevisionist Answers and a Neorealist Suggestion." Diplomatic History, Summer 1989, 419-429. Cohen, Warren I. "Vietnam: New Light on the Nature of the War?" The International History Review, February 1987, 108-116. Divine, Robert A. "Vietnam Reconsidered." Diplomatic History, Winter 1988, 79-93. Ellsberg, Daniel. Papers on the War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972. FitzGerald, Francis. Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and Americans in Vietnam. Boston: Little, Brown, 1972. Herring, George C. "America and Vietnam: The Debate Continues." American HistoricalReview, April 1987, 350-362. Herring, George C. America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996. Hess, Gary R. "The Unending Debate: Historians and the Vietnam War." Diplomatic History, Spring 1994, 239-264. Hess, Gary R. Vietnam and the United States: Origins and Legacy of War. Boston: Twayne, 1990. Kearns, Doris. "Doris Kearns: The Art of Biography." The New Republic, 3 May 1979, 27-29. Kearns, Doris. Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream. New York: Harper & Row, 1976. Kiernan, Ben. "The Vietnam War: Alternative Endings." American Historical Review, October 1992, 1118-1137. Kimball, Jeffrey P. To Reason Why: The Debate about the Causes of U.S. Involvement in the Vietnam War. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1990. Kimball, Warren. "The Cold War Warmed Over." American Historical Review, October 1974, 11191136. Kolko, Gabriel. Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience. New York: Pantheon, 1985. Krepinevich, Jr., Andrew F. The Army in Vietnam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1986. Levy, David. The Debate over Vietnam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1991. Lewy, Guenter. America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford UP, 1978. Matthews, Lloyd J. and Dale E. Brown, eds. Assessing the Vietnam War: A Collection from the Journal of the U.S. Army War College. New York: Pergamon, 1987. Paterson, Thomas G. "Historical Memory and Illusive Victories: Vietnam and Central America." Diplomatic History, Winter 1988, 1-18. Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M. The Bitter Heritage: Vietnam and American Democracy 1941-1968. New York: Fawcett, 1967. Sestanovich, Steven. "Still Burning: Reconsideration of Fire in the Lake. The New Republic, April 29, 1985, 39-42. Spector, Ronald. "What Did You Do in the War, Professor?" American Heritage, December 1986, 98-102. Summers, Jr., Harry G. On Strategy: A Critical analysis of the Vietnam War. Navato, CA: Presidio, 1982. Updated 9/29/2001 11:28 AM Copyright © 1994-2007 Vanguard University and Mary Wilson VUSC Disclaimer

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)