Session One Notes

advertisement

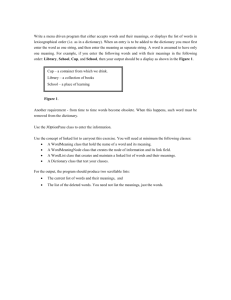

English 421 Semantics and Pragmatics Session One Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To gain a grasp of the basic meaning of semantics and pragmatics 2) To gain an understanding of various ways of explaining meaning that have previously been proposed, including dictionary definitions, mental images, and meaning and reference, and why each falls short An Introduction Questions/Main Ideas (Please write these down as Semantics as a subfield of linguistics is the study of meaning in language you think of them) Semantics deals with the meanings of words and how the meanings of sentences are derived from them To fully understand the meaning of a sentence, however, we must also understand the context in which it is used Pragmatics is concerned with how people use language within a context and why they use language in particular ways An Introduction In order to understand what “meaning” in language is, it is important to realize that it is a multifaceted phenomenon Different aspects of meaning need to be explained in different ways, so they are studied differently and are governed by different theories First: language meaning communicates information about the world around us An Introduction We can refer to persons, places and both (concrete) things and (abstract) ideas or concepts We can then assert that these things have certain properties or stand in certain relationships to one another By using sentences of a common language, one person can expand another person’s knowledge of the world A language is thus fundamentally a system of symbols An Introduction Symbols are things that stand for other things Theories of the information content of language take as basic the relationship between a word and what it refers to, or a sentence and the fact or situation it describes Of course, language can be used to talk about imaginary situations and things, like Santa Claus or unicorns, as well as actual ones (apologies to Kim Jong-un) This poses a few problems for theories based on “reference” An Introduction Second: meanings are also things that are grasped and produced in the mind of the speaker/hearer as she uses language Meanings are therefore a cognitive and psychological phenomenon as well When we ask whether the meaning of a noun like bird is more like a dictionary definition, a mental image, or the concept of the typical bird, we are asking about the cognitive aspect of meaning, not its reference An Introduction (The reference of bird is an actual bird or birds, not something in the mind) Linguists have thus studied language comprehension through laboratory experiments with human subjects as they hear and speak words and sentences Or through what children understand words and sentences to mean at various stages of the language acquisition process An Introduction Third: language meaning is a social phenomenon Relationships between the speaker and hearer come into play in all sorts of ways in determining what our utterances mean Language doesn’t just present information independent of the context of an utterance Questions, commands, suggestions, warnings, etc. involve when, where, by whom, and to whom for their appropriacy An Introduction This third facet of meaning – the appropriateness of meaning in a situation – is known as pragmatics But pragmatics and semantics interact so much that they can’t really be separated in all cases Fourth: meanings of words and sentences have a variety of important relationships among themselves, which can be studied independently of both information content and hypotheses about cognition An Introduction This includes classifying pairs of words as synonyms, antonyms, hyponyms, etc. Information content, cognitive meaning, and social (pragmatic) meaning, therefore, are complementary aspects of the general phenomenon of meaning The ability to learn and use a language would not be such a remarkably useful characteristic of our species if we could not use language to talk about all the things in our world An Introduction At the same time, language would not be possible without the mental capacity to process and produce the mental counterparts of this information and integrate it with our other thoughts and perceptions The same goes for principles of language use and context-dependence We (meaning you and I as linguists) will not have fully understood the phenomenon of meaning until all these aspects are understood (which hasn’t happened so far) An Introduction A major division in semantics, which cuts across the distinctions made thus far, is between lexical semantics, the meanings of words, and compositional semantics, the way that the meanings of whole sentences are determined from the meanings of the words in them by the syntactic structure of the sentence “the dog bit the man” “the man bit the dog” An Introduction These two sentences have the same words but not the same meaning Syntactic structure plays a role in determining sentence meaning In other words, we don’t grasp the meaning of a sentence by just putting together the meanings of the individual words involved in any old way When we think of meaning in its nonlinguistic sense, we almost always think of word meaning An Introduction We are all familiar with looking up words in dictionaries or asking someone about the meaning of a word we haven’t seen before We discuss (and argue about) exactly what a certain word means But we don’t do this nearly as often with the meanings of sentences Note that there are no dictionaries of sentences! An Introduction Every person hears and uses new sentences every day that she or he has never heard or used before These sentences, in fact, may never have been uttered before by anyone (Think about the nightly news) We understand the meanings of new sentences, and all speakers of English understand the novel sentence in (more or less) the same way An Introduction That is, we agree on its linguistic meaning, though we may differ in the further interpretation and consequences of that meaning In fact, this would be true of the meaning of any grammatical and semantically well-formed sentence you could make up (Which is why we can never have a “dictionary of all sentences”) Thus, systematic principles must exist that determine the meaning of any sentence from its syntactic structure An Introduction Along with the meanings of the individual words in it, of course Further, these principles must apply recursively That is, they can be applied again to their own output, over and over again to produce meanings for new sentences and for ever longer, more complex sentences (Thus, we can never have “the world’s longest sentence”) An Introduction Lexical semantics and compositional semantics are fundamentally different because the number of words in a language is finite, while the number of sentences is not We tend to take notice when we hear a new word for the first time We may not be able to guess what it means, even if it is formed by a semantically regular suffix (like the agentive suffice –er) But we generally never notice whether a sentence and its meaning are new to us An Introduction This is a result of the fact that we learn word meanings individually, one at a time, each independently of the other But we don’t “learn” individual sentence meanings – we simply compute them mentally and unconsciously by compositional rules So why is it so damn hard to give a meaning of “meaning”?’ What does it mean to say a given word or phrase has a certain meaning? An Introduction Here are a couple answers to this question that have been proposed Dictionary Definitions In our culture, where dictionaries are wide-spread, many people have the impression that a word’s meaning is simply its dictionary definition Just a little thought, however, shows that there must be more to meaning that this An Introduction Of course, it is true that a convenient way to find out the meaning of a word is to look it up in a dictionary Most people in our culture accept dictionaries as providing unquestionably authoritative accounts of the meanings of the words they define This leads people to believe that the dictionary definition of a word more accurately represents the word’s meaning than does an individual speaker’s understanding of the word An Introduction People who write dictionaries, however, arrive at their definitions by studying the ways speakers of the language use different words From the linguist’s point-of-view, there is simply no higher authority than the general community of native speakers of the language A word’s meaning is determined by the people who use that word, not a dictionary (Sorry, Miss Schlenker) An Introduction The view that a dictionary definition is all there is to a word’s meaning poses an immediate serious problem when one considers that in order to understand the dictionary definition of a word, one must know the meanings of the words used in that definition But understanding the meanings of these words involves understanding the meanings of the words in their definitions, and so on An Introduction Sometimes the circularity of a set of dictionary definitions becomes comical For example: one English dictionary defines divine as “being or having the nature of a deity” But defines deity as “divinity” Another example: another defines pride as “the quality or state of being proud” But defines proud as “feeling or showing pride” An Introduction Notice that you would also have to know the meanings of such words as “being,” “having,” “nature,” “quality,” “state,” and even “the” and “or” Dictionaries are essentially written to be of practical aid to people who already speak the language, not to make theoretical claims about the nature of meaning Some people do, of course, learn words through dictionaries, but dictionary definitions can’t be all there is to the meanings of words An Introduction Mental Images Another possible explanation is a word’s mental image This is attractive, since words do seem to conjure up particular mental images For example, close your eyes and think of the Mona Lisa This may well cause an image of Da Vinci’s painting to appear in your mind Is it the same image, though? It is 30" high by 20 7/8" wide An Introduction Once again, however, this can’t be all there is to a word’s meaning Different people’s mental images may be very different from each other, without the words really seeming to vary much in meaning from individual to individual For a student, the word lecture will probably be associated with an image of one person standing at the front of the room, and may include the back’s of fellow students’ heads An Introduction For the teacher, however, it is more likely to consist of an audience of students sitting in rows facing forward The two different perspectives are actually quite different Even so, both the student and the teacher understand the word lecture as meaning more or less the same thing, despite the different mental images How can a word mean the same thing if it conjures up different images? An Introduction Another problem with mental images is that the image associated with a word tends to be of a typical or ideal example of the kind of thing the word represents Words are used, however, to represent a wide range of things, any one of which may or may not be typical of its kind For example, close your eyes and think of a bird For most of you, the bird probably looked like this An Introduction The Robin An Introduction However, this is also a bird: An Introduction And so is this: An Introduction And even this: Unless Mitt Romney gets his way An Introduction Since ostriches and penguins and Big Bird are birds too, any analysis of the word bird must take this into account Any complete analysis should provide some indication of what the typical bird is like, but must also make some provision for atypical birds A further problem – many words, perhaps even most, simply have no clear mental images attached to them Examples: forget, the, further, perhaps An Introduction Meaning and Reference As previously mentioned, language is used to talk about things in the outside world It is reasonable, then to consider the actual thing a word refers to – its referent – as one aspect of a word’s meaning Once again, it would be a mistake to think of reference as all there is to meaning To do so would be to tie meaning too tightly to the real world An Introduction If meaning were defined as the actual thing an expression refers to, what would we do about words for things that don’t exist? There is no real-world referent for the words Santa Claus, yet these words are not meaningless (they create a mental image, for example) Language can be used to talk about fiction, fantasy, or speculation Any complete theory of meaning must take this into account An Introduction Even some sentences about the real world appear to present problems for the idea that a word is just its referent If meaning is the same as reference, then if two expressions refer to the same thing, they must mean the same thing It would then follow that you should be able to substitute one for the other in a sentence without changing the meaning For example: An Introduction Barack Obama and The winner of the 2012 presidential election both refer to the same real-world referent So the following two sentences mean the same thing: 1) Barack Obama is married to Michelle Obama 2) The winner of the 2012 presidential election is married to Michelle Obama These two sentences do indeed seem to describe the same fact An Introduction However, consider the following substitutions: 3) Robin wanted to know if Barack Obama was the winner of the 2012 presidential election 4) Robin wanted to know if Barack Obama was Barack Obama These sentences don’t mean the same thing, and don’t even describe the same fact Any theory has to describe why substitutions like this don’t work An Introduction Truth Conditions and Truth Value It is not necessary to give up the key insight that meaning as reference provides, however Meaning involves a relation between language and the world To help avoid problems, it may be beneficial to think about how a sentence relates to the world, rather than just how individual words relate to the world But sentence meaning is a difficult concept to define An Introduction Instead of being so direct, linguists have instead taken a more indirect route Instead of asking “What is sentence meaning?” they take an indirect approach that asks “What do you know when you know what a sentence means?” An example: Barack Obama is asleep To know what this sentence means is not the same as knowing that Barack Obama is actually asleep or not An Introduction Any English-speaking person knows what this sentence means, but relatively few people know at any given time whether Barack Obama is asleep or not What English speakers who understand the sentence know is what the world would have to be like in order for the sentence to be true That is, anyone who knows a sentence’s meaning knows the condition under which it would be true An Introduction They know its Truth Conditions You know that for the sentence Barack Obama is asleep to be true, the individual designated by the words Barack Obama must be in the condition designated by the words is asleep If, in addition to the truth conditions, you in fact know whether or not the sentence really is true, then you also know another facet of the sentence’s meaning – its Truth Value An Introduction The truth conditions and truth value of a sentence relate it to the world, but in a somewhat different way than ordinary reference does Sentences about Santa Claus, for example, do have truth conditions, even thought the words Santa Claus have no real-world referent What you know is “What would Santa Claus have to be like if he were real” An Introduction In other words, you can describe the conditions under which a sentence containing these words would be true But describing its truth value is much less clear The sentence Santa Claus is asleep is neither true nor false The subfield of semantics called Supposition studies this An Introduction This helps explain the previous problem The truth conditions for Barack Obama and The winner of the 2012 presidential election are different Thus, they cannot be freely substituted for each other But even truth conditions are only part of the explanation They work well for literal meaning, but what about questions? Wishes? Orders? There is still much to be explained, especially in relation to the situation where a sentence is used Summary/Minute Paper: