Arguments: Finding, Evaluating, and Building Them

advertisement

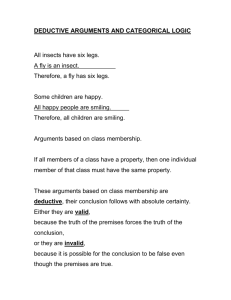

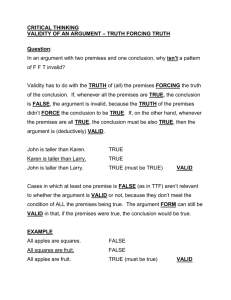

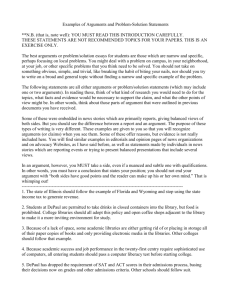

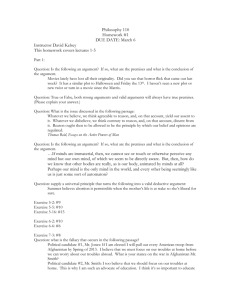

ARGUMENTS FINDING, EVALUATING, AND BUILDING THEM Empirical versus normative statements When we are talking, reading, or writing about controversial subjects we want to do more than simply state our opinion; we want to justify it. In other words, we want to tell our audience (readers, listeners, or even just ourselves when we are thinking about what our opinion on an issue should be) why we think one way rather than another. For instance, it is not enough to say simply “Executing minors is wrong.” If we are to persuade others of our view, or even just show that our view is a considered one—one which we are not simply pulling out of a hat, but which we truly believe in—we need to give our reasons for thinking that it is correct. If we are dealing with factual disputes, our job is usually straightforward (if not always easy). If we say, for instance, “It’s my opinion that it is five miles to Town Lake from here,” all we need to do is measure the distance with a pedometer or odometer or consult a map to prove our point. That is, if someone disagrees with us, there is a simply way to confirm (or disconfirm) our statement. These are called empirical statements, because they can be proven through experience—the watching of the odometer or measuring on the map. Not only is this straightforward, but it is terminal in nature. This is because given the possibility of proving our point, we can be done with the dispute. It is decideable, and once done, we needn’t continue to argue over it. Controversial social issues, such as the ones that you are dealing with in your Position Papers, are very different than empirical disputes. For there is usually no way to prove that your opinion is right. Consider how you would do so with the statement above regarding the wrongness of executing minors. You might offer the following points: 1. Minors are not mature enough to know what they are doing. 2. We hold the parents of minors accountable for many of their needs (such as food, housing, and education), so we should hold them accountable for the minors’ actions too. 3. It is wrong to hold those who aren’t granted adult status in society (by being allowed to vote, join the army, marry without parental permission, drink, etc.) to adult standards. But let’s see how we might prove these reasons for opposing such executions. With regard to number 1, how should we define “mature” and what would count as “mature enough”? While psychologists and criminologists would no doubt be able to offer the beginnings of an answer to these questions, the concept is obviously still troublesome. For one thing, maturity is an internal state which we can only guess at by things a person says and does. Moreover, maturity is highly changeable not only within a single person—consider the early teen who one moment seems to be completely rational and mature and the next is in a rage over seemingly nothing—but among different people. We all know cases of a surprisingly mature 8 year old, and an incredibly immature 40 year old. Thus, as a matter of proof, this claim will not do because maturity itself is not an empirical concept. 2 and 3 are problematic as well. This is, again, because they rely on concepts which are non-empirical. While it is true that we do legally hold parents responsible for care of minors (especially the very young) and could prove it empirically by showing anyone who doubted it the laws, the statement is followed by one which cannot be so proven, namely that we should hold parents accountable for their actions too. The word “should” refers to the future—how we ought to act next, or ideally. In using it, we are implicitly admitting that it is not how we are acting now. (Think about when you say “I really should get going on my homework” –you would only say it when you weren’t presently doing it. Likewise if you say “It sure would be good if I got going on my homework.”1) The bottom line is that words like “should,” “ought,” “good,” “evil,” “right,” and “wrong” all refer to an ideal to be achieved (or harm to be avoided) rather than the present state of affairs. Such words are the opposite of empirical ones and are called normative insofar as they appeal to norms, or values to be sought after. 1 There is, of course, a way we use good in the present tense, namely that it is good that I do it. Usually, however, when we are in the position of arguing for something, we are saying at minimum that others should behave accordingly. Normative statements cannot be proven true or false like empirical ones can. Instead, they must be argued for. That is, when you are presenting an opinion on a normative issue (such as you will be in your Position Paper), your task is to show that it is the best available option, rather than the only one which is true. And for this you will need to present arguments. To sum up, the difference between empirical and normative statements is as follows: EMPIRICAL STATEMENTS FACTUAL VERIFIABLE TRUE OR FALSE SIMPLY DESCRIBE THE WORLD DECIDABLE NORMATIVE STATEMENTS VALUE-LADEN JUSTIFIABLE NEITHER TRUE NOR FALSE PRESCRIBE OR PROSCRIBE ARGUED FOR Arguments: Definition and Examples Arguments are defined by Chaffee as “A form of thinking in which certain statements (reasons) are offered in support of another statement (a conclusion)” (452). Usually, we find arguments embedded in texts such as essays, editorials, court cases, etc. But it is useful to consider them in isolation of the prose when first trying to identify and evaluate them. The best way to do this is to read the article (or editorial, chapter, etc.) through first, and then determine what the author is trying to establish. This will be the conclusion of the argument (it will also usually be the thesis of the essay). Notice we are working backwards here—starting with the ending conclusion and then asking how the author arrived at it. This is quite natural because we all tend to have opinions about a vast array of issues, but we may not always know why we hold those particular views. In other words, we may have conclusions without reasons (or as we shall sometimes refer to them, premises) to support them. Such opinions are a dime a dozen and worth very little in serious dialogue or writing. This is not to say it’s wrong to have an ungrounded opinion; only that if you want to assert it with any force—or if it is one which has important impact on your or others’ well-being—it is best to seek to justify it by finding out if there are valid reasons for holding it.2 Evaluating Arguments After determining what the argument (the conclusion and the premises) is, we need to evaluate it. Recall that since normative statements can’t be proven true or false, we have to be satisfied, in a sense, with better or worse. However, some arguments will be indeed be better than others and showing that the other side has a lousy argument— one that isn’t logical--will serve as a justification. Others (probably including those you will be dealing with in your Position Paper) will be more difficult to choose between. In this case, what we have are two good, logical arguments; choosing one becomes a matter of thinking about which entails or protects what you value you most (see “The Ruggiero Method”). Consider the following arguments regarding what was once a shockingly common practice in the United States, the forcible sterilization of the mentally incompetent, “feeble minded,” poor, criminally inclined, and other “defectives,” a practice called “eugenics” (and in place in the United States well before Hitler ordered it). (An excellent film of one of state’s laws is The Lynchburg Story, available through the Scarborough Philips Library.) Again, the point is to show that while we cannot prove one to be “true” and the other “false,” in many cases—this one quite clearly included—we can certainly say that one is better than the other. The argument against forcible sterilization is overwhelmingly better than the one in favor of it. We show this by looking at the premises and determining whether they are true or not (or if normative, plausible or not), as well as considering whether the premises actually lead us to the conclusion. Argument A: We Should Have Forcible Sterilization Programs: We also have many opinions which don’t have moral content and which we don’t have to support – in my opinion I like donkeys more than horses. All I’m doing is stating my preference; I’m not trying to get you to see things the same way. In other words, there is no “ought” to the matter. 2 1. 2. Feeble-mindedness, criminality, poverty, etc. are inherited traits. Based on: concerns of “degeneration of the races,” postmortem studies (of one) showing one famous criminal to have a quality rarely found in humans, but often found in rats; a report from a prison guard that “the appearance of prisoners alone [shows that] a large portion of them were born to be criminals”. Such traits weaken and thus harm the state and the population at large. 3. Therefore, those who have such traits should be forcibly sterilized for the good of the state (Reilly 597-606). Argument B: We Should Not Have Forcible Sterilization 1. There is no reliable scientific evidence that “feeble-mindedness,” criminality and poverty are hereditary. 2. “Marriage and procreation are fundamental to the very existence of the survival of the race. The power to sterilize, if exercised, may have subtle far-reaching and devastating effects. In evil or reckless hands, it can cause races or types which are inimical to the dominant group to wither and disappear … He [who is forcibly sterilized] is forever deprived of a basic liberty” (Skinner v. Oklahoma). 3. Therefore, no one ought to be forcibly sterilized by the state. It goes without saying that the first premise in Argument A is utterly false as stated and scientific evidence will easily show this. (Notice this is an empirical statement rather than a normative one and thus, easier to accept or dismiss.) If so, the argument is unsuccessful (though it is still valid, but don’t worry about that right now). Argument B, on the other hand, has true, or plausible, premises which directly lead to the conclusion. It is thus, a better argument and one that rational persons should choose. Validity and Soundness We said that there are two things to check when evaluating an argument: i) Are the premises true? ii) Do the premises lead to the conclusion? Obviously, if one or all of the premises are false, we are not terribly interested in the conclusion that they may or may not lead to. For remember, what we are doing in arguments is offering reasons for the conclusion that we are asserting. If those reasons are false (or highly implausible, e.g., “2 year old children know exactly what they are doing and should be treated as adults”), then we have failed to support or justify our conclusion—the whole point of the enterprise. But what do we mean by (ii)? What has to happen in order for us to say that the premises “lead” to the conclusion? The technical answer to this is to say that it means an argument is valid, which in turn is defined as being one in which there is no case in which the premises are all true and the conclusion is false.3 Less formally, what we mean by saying that the premises lead to the conclusion is that if you accept the premises (i.e., think they are true or plausible), then you must accept the conclusion; it would be irrational to do otherwise. Consider the following argument often used by logicians: 1. All men are mortal . 2. Socrates is a man. 3. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. Now imagine that someone tells you that she believes 1 and 2 to be correct, but denies the conclusion. What would you say to her? Can you really believe on the one hand, that every single man is mortal and Socrates is a part of that group, and yet go on to deny that Socrates is mortal? You can, of course, but not reasonably. In contrast,. consider the following invalid argument: 1. Roses are red. 2. Violets are blue. 3. All flowers of either red or blue. In this, case, it is perfectly reasonable to accept both premises as being true, and yet deny the conclusion. That is, the true premises do not lead to the conclusion—they don’t give you good reasons for accepting it. The argument is invalid. 3 Notice that the short argument about 2 year olds, actually meets this requirement and thus, is (quite oddly) a valid (but not sound) argument. For while the premise is obviously false, so is the conclusion. Therefore, this isn’t and a case in which a) the premises are true and b) the conclusion is false. (a) isn’t satisfied so we needn’t worry about checking for invalidity. These details go beyond the kind of informal logic that we need for critically thinking about arguments. Now if we put the two conditions listed above together—that all the premises be true and that the premises lead to the conclusion—we get what are called sound arguments. A sound argument is one which is a) valid (it’s not the case that the premises are true and the conclusion is false), and b) has only true premises.4 These are the arguments which will count as better than those which fail either one of these requirements. Examples This is not meant to imply that you will always be able to pick between arguments based on validity and soundness. You will more often than not be faced with two opposing arguments which meet both criteria. At that point you will then need to assess and analyze based on the values, obligations, and consequences, involved in the premises (the Ruggiero Method). However you should always check for soundness. This is something you’ve been doing for years, though probably with these terms or format. It’s pretty clear that we need to look for the evidence (or plausibility in the case of normative statements) behind anyone’s argument. Your scholarly research will be largely concerned with this; what studies are there? Has this law or policy been found to be constitutional? Why would specialists in the field (rather than “journalists” for the National Enquirer) think this? For instance, consider the following dispute: Should we adopt uniform newborn screening for rare medical conditions in all states? (Gina Kolata, a science writer for The New York Times, reported on this controversy on February 21, 2005.) Proponents’ Argument: 4 Note here we have the counterintuitive fact issue that you can have a valid argument which is made up of complete nonsense—all you need is one false premise and the argument—strangely—comes out to be valid (but not sound). This is because of the technical definition of validity—that there be no case in which the premises are true and the conclusion is false. If one or more of the premises is not true, then this won’t happen, thus the argument will be valid. This need not concern you at this stage, however, for what we are interested in is arguments which are both valid and sound. 1. Early diagnosis of serious and devastating diseases can improve the life chances of the patient as well as his or her quality of life. 2. Early diagnosis can also help parents and doctors avoid embarking on “a medical odyssey to find out what is wrong with their child” (front page) which is expensive, distressing, and potentially dangerous for the undiagnosed child. 3. Therefore, early testing in the form of newborn screening (and hence, diagnosing) should be done. Opponents’ Argument: 1. Except for a minority of the diseases for which screening exists, treatment is unavailable or uncertain with regard to efficacy. 2. If there is no reliable treatment for the medical condition, early detection will not improve the patient’s life in any way. 3. Therefore, newborn screening is usually pointless and should not be mandated.5 Opponents also argue as follows: 1. Many of the conditions—genetic possibilities—uncovered may never be manifested (or expressed), thus treatments may be in vain and even dangerous for the patient. 2. Therefore, newborn screening should not be done. In this case, we are faced with a far more difficult task than in the comparison of arguments for and against forcible sterilization. All of the arguments are valid—that is, if we accept the premises, we must endorse the conclusion as well. However, are they all sound? Should we accept all of the premises? This is an extremely complicated issue and clearly demonstrates the need for further research. Moreover, we are faced with the further complication of predicting the success, or lack thereof, of treatments, as well as the number of patients who are positively affected and those who gain no benefit or are even harmed. We need not solve these problems here (thankfully!). Rather, the point of 5 Whether parents should be able to have the screening done is a very different question. But your Position Paper will be about social questions–what our society at large should do—rather than personal decisions. the example (from an everyday newspaper story: evidence of the complexity of our world and the need for clear thinking) is to show first, that choosing between proponents and opponents’ arguments can be a very complicated affair, and secondly, that being clear on precisely what the arguments are is an essential first step. Exercises: As an exercise, try to construct arguments for the following normative claims (regardless of your own views on the matter): 1. Execution of those who commit capital offenses when they are minors is legitimate. 2. Same sex marriage ought to be permanently banned 3. Meat produced in ways that cause animals to suffer before slaughter ought to be banned. 4. Cell phone use in cars (including head sets) should be banned. 5. Banning smoking in restaurants and bars is legitimate. 6. There should be no grades in universities and colleges. WORKS CITED Chaffee, John. Thinking Critically 7th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. Kolata, Gina. “Panel to Advise on Tests on Babies for 29 Diseases.” The New York Times. 21 Feb. 2005. National ed.: A1. Print. The Lynchburg Story: Eugenic Sterilization in America. Dir. Bruce Eadie. Worlview Pictures, 1995. DVD. Reilly, Phillip. “Eugenic Sterilization in the United States.” Contemporary Issues in Bioethics 4th ed. Eds. Tom L. Beauchamp & Walter Leroy. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1994. 597-606.