ICF: A guide to assistive technology decision-making

advertisement

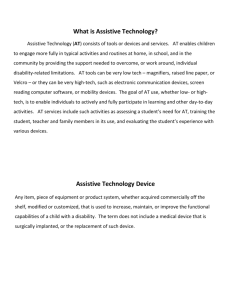

ICF: A GUIDE TO ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY DECISION-MAKING Petra Karlsson University of Western Sydney Sydney, NSW Abstract The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Function, Health and Disability (ICF) offer a model to guide and integrate the complex aspects of assessment for assistive technology. Assessments based on the ICF will assist professionals to understand the intended individual’s need, facilitate collaboration across agencies and prioritise goals for intervention. Research tells us that not one instrument alone is able to provide an evidence-based assistive technology specific assessment. However, the ICF components are integrated in some well-established assessment instruments. In the assessment process, professionals assessing assistive technology needs must rely on their knowledge, experience and clinical reasoning. This in combination with using well-established assessment and outcome instruments ensures evidence-based decision-making, when recommending assistive technology. This paper outlines the ICF model and its application to guide the use of existing evidence-based assessment and outcome instruments that are applicable for most disabilities, settings and types of assistive technology. Key words assistive device, assistive technology, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model, service delivery process 1. Introduction Assistive technology is designed to provide functional benefits and to facilitate participation for a person with a disability (World Health Organization, 2002). However, research shows that there is a high level of device abandonment, even with what appears to be a well matched device (M. J. Scherer & Craddock, 2002). Studies on device abandonment, often explained by inefficient assessments and intervention processes (Judge, 2002; M. J. Scherer & Craddock, 2002), have led to the development of assistive technology specific outcome measures to evaluate the satisfaction and effectiveness of a device. There is a lack of evidence- based procedures that are specific to assistive technology provision. Although the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) was not specifically developed to guide assistive technology assessment, the literature shows that it lends itself as a descriptive model for the assistive technology assessment process. ICF captures the complex aspects of the impact of assistive technology and its service delivery process and can assist the professional in decision-making (Bernd, Van Der Pijl, & De Witte, 2009). This paper outlines the ICF model and its application to guide the use of evidence-based assessment and outcome instruments that are applicable to most disabilities, environments and types of assistive technology. 2. Assistive technology The World Health Organization defines assistive technology as any device or system that enables a person to perform a task that would otherwise be too difficult to execute and which facilitates a task being performed (World Health Organization, 2004). Assistive technology includes both devices and services. Assistive technology services are defined as a service that support assistive technology assessment, acquisition and device use (Bausch & Jones Ault, 2008). 3. The International Classification of Functioning The International Classification of Functioning, known as ICF, is widely used to describe and measure health and health-related state outcomes. It provides a common language and framework to describe health and disability. ICF is a classification of health and health-related domains. The domains describe changes in body function and structure, what a person is able to do, their level of capacity, what they actually do, and their level of performance. Functioning in ICF refers to all body functions, activity and participation, while disability is used to describe impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In ICF, disability and functioning are seen as outcomes from interactions between health conditions and contextual factors (World Health Organization, 2002). Initially the ICF looks like a simple health classification, but it can be used for a wide range of purposes. In service provision, practical issues on the individual, institutional and social level can be addressed. On the individual level, ICF can assist in assessments to determine the person’s level of functioning and facilitate communication among health professionals, social work and community agencies. At the institutional level, ICF can be used for a number of purposes; educational and training purposes; resource planning and development; to answer questions such as; what services will be needed and how useful are the service provided. At the social level, ICF helps to identify the needs of persons with various levels of disability, impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. Environmental assessments can be used to identify facilitators and barriers to support a more accessible environment for the person (World Health Organization, 2002). In light of the above, the ICF allows for an analysis of the effectiveness of assistive technology through the domain of user functioning (ICF functioning) along with factors in the environment and in the person (ICF contextual factors). 4. Using the ICF to structure assistive technology assessment The ICF disability and functioning are seen as outcomes between health conditions and contextual factors. In the first part; disability and functioning includes components of body function, body structures and activities and participation. In the second part; contextual factors include environmental factors and personal factors (World Health Organization, 2002). The ICF checklist, an instrument developed to be used along with the ICF, captures disability and functioning and contextual factors. The checklist assists the service provider to assess the presence of an impairment, using a five point scale, to grade the impairment of function and structure (no impairment, mild, moderate, severe and complete)(World Health Organization, 2003). The checklist can be used across disabilities, age groups and settings. The only evidence based assistive technology specific model, developed to match the ICF and its checklist found in the literature, is the Matching Person and Technology (MPT) model (Bernd, et al., 2009; M. J. Scherer & Craddock, 2002). The MPT is the most published model that is specific to assistive technology assessment (Bernd, et al., 2009). It was developed to address the environment, the person and the technology, factors that need to be considered when evaluating a person’s need for assistive technology (M. J. Scherer & Craddock, 2002). The MPT supports a collaborative partnership between the service providers and the user (M. Scherer, Sax, Vanbiervliet, Cushman, & Sherer, 2005). The Assistive Technology Device Predisposition Assessment consumer form (ATD PA), a part of the MPT assessment battery, is compatible with ICF and measures the impact of technology using the ICF domains. The ATD PA items ask the user to rate their predisposition to using the assistive technology that is being considered, to better match technology with the person and therefore minimize device abandonment. ATD PA is developed for adults (M. Scherer, et al., 2005). For families with children aged 0-5, an assessment form called Matching Assistive Technology and Child (MATCH) is developed (Sherer, 1997). The literature tells us that there is a lack of evidence-based procedures for assistive technology provision (Bernd, et al., 2009). Where the MPT is not applicable or available, the ICF framework can guide the service provider in assistive technology decision-making and to the use of evidence-based outcome measures. Through evidence-based practice, improvements in the outcomes of interventions and services in assistive technology as well as in other health areas, can be achieved (Adams, 2003). The outcomes guide us as to whether an assessment and implementation were successful. 4.1 Disability and functioning Body functions and Body structures are the physiological, psychological and anatomical functions of the body. The ICF checklist has a list of mental functions; sensory function and pain; voice and speech functions; respiratory systems; neuromusculoskeletal and movement related functions, to mention a few. The checklist will assist the service provider to assess if more specific assessment related to cognition; speech and communication; hand function; and mobility will be required. When assistive technology is successful, it reduces or removes barriers, to allow the person to take part in activities (Jutai, Fuhrer, Demers, Sherer, & DeRuyter, 2005). The ICF checklist assists the service provider to elicits what capabilities and limitations the user’s experience in activities and participation related domains. Examples of relevant domains are: learning and applying knowledge; speaking; getting around inside and outside the home; self-care; interpersonal relationships; and social life etc. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) was developed to capture the client’s individual occupational performance as an outcome measure. It is a published copyright semi-structured interview instrument (Law, et al., 1999). COPM is not assistive technology specific, but looks at the needs of the assistive technology user from a client-centred perspective. Applied with other instruments it has been found to be a useful tool for assistive technology assessments (Bernd, et al., 2009). COPM looks at three important sections of daily living; self-care, productivity and leisure. When identifying problem areas with the help of COPM, the nature of the domains of productivity, leisure and self-care, may prompt service providers to activity oriented goals rather than goals of participation, although the instrument support both goals (Sakzewski, Boyd, & Ziviani, 2007). The Goal attainment scaling (GAS) was first introduced in 1968 to evaluate mental health services (Kiresuk & Sherman, 1968). Today it is widely used in pediatrics, rehabilitation and mental health (Steenbeek, Ketelaar, Lindeman, Galama, & Gorter, 2010). GAS measures the change in response to individual goal-setting. For each goal, five pre-determined levels of outcomes are described. GAS requires no additional qualification to administer, but training is recommended along with problem-solving skills. GAS is flexible and suitable to use for unique goals. GAS can be developed with or without client involvement. However, client or family involvement when developing goals has shown to result in a higher number of successfully implemented goals (Østensjø, Øien, & Fallang, 2008). The Individually Prioritised Problem Assessment (IPPA) is a generic instrument to measure the effectiveness of any assistive technology provision. The aim with this instrument is to measure the degree of change. The service provider facilitates, through an interview, the user to identify problem areas. This is similar to how COPM is administered. The user rates the importance and level of difficulty. IPPA has been found to be a sensitive measure of change (Wessels, et al., 2000; Wessels, et al., 2002). In sum, the COPM, GAS and IPPA are examples of the few instruments, that after intervention are evidence-based and unique in that they are sensitive to measure change (Cusick, McIntyre, Novak, Lannin, & Lowe, 2006; Sakzewski, et al., 2007). COPM and GAS have the advantage that they can be used with clients of any age, with any disability, using any form of assistive technology. A combination of these instruments offer service providers additional evidence-based solutions for assessment and outcome measure in assistive technology, as an alternative or complement to the MPT. 4.2 Contextual factors An assessment is defined by Law, Baum & Dunn (2005) as the instruments used to collect relevant information during the assistive technology evaluation. In the assessment process there are many factors to consider; what the person wants and needs to, do as well as the environment in which the activity will take place. Examples of contextual factors are the external environmental factors such as support and relationships; service, systems and policies; climate; terrain; and technology. Examples of internal personal factors are; the gender, age, social background, education, profession past and present experience (World Health Organization, 2002). The ICF checklist provides the service provider with a template to also collect demographical data, and information regarding diagnosis and heath conditions (World Health Organization, 2003). Investigating personal, environmental and health related factors may identify the factors that influence the user’s functional ability (Jutai & Day, 2002). Environmental and personal factors can change over time (M. Scherer, Jutai, Fuhrer, Demers, & Deruyter, 2007). They may be the reason for assistive technology use or abandonment (Jutai & Day, 2002). The Psycho-social Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS) measures the psycho-social impact of an assistive technology device on a user. PIADS aims to describe the impact of a device on the person’s functional independence, well-being and quality of life. By investigating the psycho-social impact the authors hoped that it will help to explain the reason for device use or abandonment. The 26-item scale looks at competence, adaptability and selfesteem that can be administered by a self-report questionnaire or through interviews (Jutai & Day, 2002). The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST 2.0) was designed as an outcome measure. The QUEST 2.0 evaluates the users satisfaction with the assistive technology’s attributes, such as its weight, ease of use, comfort and effectiveness. The QUEST 2.0 is aligned with the environmental domain of ICF. The first version of the QUEST was adapted from the MPT model (Demers, Weiss-Lambrou, & Ska, 1996). The QUEST 2.0 can be used with adolescents, adults and the elderly (Demers, Weiss-Lambrou, & Ska, 2002). A child version of the QUEST 2.1 has recently been developed (Murchland & Dawkins, 2010). The QUEST 2.0 has three scores; device, services and total QUEST. The QUEST 2.0 can be self-administered using a pen and paper or administered through an interview. It is a generic outcome measure that can be applied to a wide range of assistive technology devices. The user can add additional items, such as speed. These scores are reported separately to the overall QUEST score. The psychometric properties of the instrument have mainly been tested by the developers, but show promising results for reliability and validity (Demers, et al., 2002). 5. Conclusion The ICF, when used with the ICF checklist, is a useful tool to assess the user’s abilities and assistive technology needs. It is freely available from the World Health Organization website. The MPT is reported to be an evidencebased specific assistive technology assessment that is compatible with the ICF. The MPT is filling a gap of instruments that consider the interactions among device characteristics, its user and the environment. Furthermore, the COPM, GAS and IPPA are evidence-based instruments that are useful in assistive technology assessments and outcome measures, which identify efficient strategies for achieving activity and participation goals. These instruments are sensitive to measure change, a feature valuable for evaluating any intervention for clinical or research purposes. The literature suggests the use of the QUEST 2.0 and the PIADS when evaluating contextual factors such as device features and the enhancement of user’s well-being. With improved assessments, guided by evidence-based practice and the ICF. The service providers, in collaboration with the clients, are supported in the assistive technology decision-making. Correspondence Email: p.karlsson@uws.edu.au Petra Karlsson University of Western Sydney Locked Bag 1797 South Penrith DC, NSW, 1797 Phone: +61 (0)2 4736 0879 References Adams, E. (2003). Optical devices for adults with low vision: A systematic review of published studies of effectiveness: VA Technology Assessment Program: Office of Patient Care Services. Bausch, M. E., & Jones Ault, M. (2008). Assistive technology implementation plan a tool for improving outcomes. Teaching exceptional children, 41(1), 6-14. Bernd, T., Van Der Pijl, D., & De Witte, L. (2009). Existing models and instruments for the selection of assistive technology in rehabilitation practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Thera;y, 16, 146-158. Cusick, A., McIntyre, S., Novak, I., Lannin, N., & Lowe, K. (2006). A comparison of goal attainment scaling and the Candadian occupational performance measure for pediatric rehabilitation research. Pediatric Rehabilition, 9(2), 149-157. Demers, L., Weiss-Lambrou, R., & Ska, B. (1996). Development of the Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST). Assistive technology, 8, 3-13. Demers, L., Weiss-Lambrou, R., & Ska, B. (2002). The Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST 2.0): An overview and recent progress. Technology and Disability, 14`, 101-105. Judge, S. (2002). Family-centered assistive technology assessment and intervention practices for early intervention. Infants and Young Children, 15(1), 60-68. Jutai, J., & Day, H. (2002). Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS). Technology and Disability, 14, 107-111. Jutai, J., Fuhrer, M., Demers, L., Sherer, M., & DeRuyter, F. (2005). Toward a taxonomy of assistive technology device outcomes. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 84(4), 294-302. Kiresuk, T., & Sherman, R. (1968). Goal attainment scaling: A general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(6), 443-453. Law, M., Baum, C., & Dunn, W. (2005). Occupational Performance assessment. In C. CH, C. Baum & J. Bass-Haugen (Eds.), Occupational Therapy Performance, Participation and Well-Being. Thorofare: SLACK Incorporated. Law, M., Polatajko, H., Pollock, N., McColl, M., Carswell, A., & Paptiste, S. (1999). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (3 ed.). Toronto, ON: CAOT Publications ACE. Murchland, S., & Dawkins, H. (2010). Development and utility of the QUEST 2.1 Childrens version. Paper presented at the ARATA 2010, Assistive technology, Tip of the Iceberg. Retrieved from www.arata.org.au/.../papers/.../MURCHLAND_sonya_QUEST2.1_pape r.doc Østensjø, S., Øien, I., & Fallang, B. (2008). Goal-oriented rehabiliation of preschoolers with cerebral palsy-a multi-case study of combined use of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and the Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS). Developmental neurorehabilitation, 11(4), 252-259. Sakzewski, L., Boyd, R., & Ziviani, J. (2007). Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5-to 13-year-old children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 232-240. Scherer, M., Jutai, J., Fuhrer, M., Demers, L., & Deruyter, F. (2007). A framework for modelling the selecton of assistive technology devices (ATDs). Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 2(1), 1-8. Scherer, M., Sax, K., Vanbiervliet, A., Cushman, L., & Sherer, J. (2005). Predictors of assistive technology use: The importance of personal and psychosocial factors. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(21), 1321-1331. Scherer, M. J., & Craddock, G. (2002). Matching person and technology (MPT) assessment process. Technology and Disability, 14, 125-131. Sherer, M. (1997). Matching assistive technology and child: A process and series of assessments for selecting and evalutaing technologies used by infants and young children. Webster, NY: Institute for Matching Person & Technology. Steenbeek, D., Ketelaar, M., Lindeman, E., Galama, K., & Gorter, J. (2010). Interrater reliability of goal attainment scaling in rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy. Archives Physical Medicine Rehabilitation, 91(3), 429-435. Wessels, R., de Witte, L., Andrich, R., Ferrario, M., Persson, J., Oberg, B., et al. (2000). IPPA, a user-centred approach to assess effectiveness of assistive technology provision. Technology and Disability, 13, 105-115. Wessels, R., Persson, J., Lorentsen, Ø., Andrich, R., Ferrario, M., Oortwijn, W., et al. (2002). IPPA: Individually Prioritiesed Problem Assessment. Technology and Disability, 14, 141-145. World Health Organization. (2002). Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health ICF. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf. World Health Organization. (2003). ICF Checklist version 2.1a, Clinical Form for International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Retrieved from http://e-bility.gr/eutexnos/Includes/icf-checklist.pdf. World Health Organization. (2004). A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. Retrieved from http://www.who.or.jp/AHP/docs/vol5.pdf.