LiuH_0310_sml. - ROS Home - Heriot

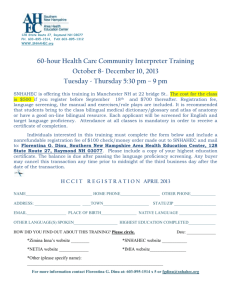

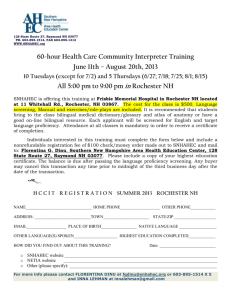

advertisement