Lai du Laustic - The FreeZone : Midwestern State University

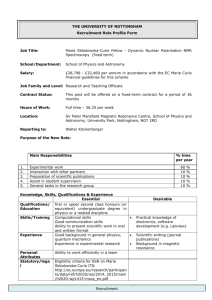

advertisement

Betrayal and Redemption in Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic Stuart McClintock Marie de France’s Laustic is one of several lais that treats adultery. In two of her lais that handle this subject, Bisclavret and Eliduc, she condemns the characters. More often she looks favorably upon it, such as in Guigemar, Yonec, Chevrefoil and this lai, in which love trumps an unhappy or arranged marriage to an old or jealous husband. In Laustic, she depicts three noble characters, the mal mariée, the brutish husband, and the young bachelor lover who all betray the ideals of their class out of lust and jealousy. The lovers’ affair is discovered because of their démesure, and they are tragically separated forever without ever consummating their love. However, they ultimately redeem themselves for their imperfect behavior through a noble act that transforms erotic to spiritual love. Marie makes the reader aware of the three characters’ fall from grace by first setting them up as models of their class. She begins the lai with a broad view of the characters that highlights their noble attributes established through public perception of their behavior and character. She then narrows the narrative and shows them in their private world where they all behave differently from the ideal established in the introduction. As the narrative narrows, Marie allows only the reader to witness their actions in private that tarnish their nobility. The bachelor pursues his neighbor’s wife with little explanation of cause; she accepts his love because it is convenient and because he is more exciting than her husband. The husband is jealous and proves to be a brute by slaughtering the bird that both symbolizes and facilitates the love of his wife and her lover. As in other of Marie’s lais, this marriage is not a source of joy, mutual respect, or trust. The husband and wife deceive each other, and they treat each other badly. The Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ marriage for the wife confined in her chateau is a prison. Marie condones the wife’s rebellion against her husband and her love affair with her neighbor because love’s joy triumphs over duty’s misery. Although the husband shatters the idyll between the wife and her lover so that they can never see each other again, they create a memorial of their love in the form of a dead bird wrapped in samite for which the bachelor makes a magnificent case. The memorial also creates a new kind of spiritual love that will endure and that ennobles them. They regain the stature that they had lost because their behavior embodies the true definition of courtly love rather than the one based on the decorum that defined noble behavior at the beginning of the lai. Marie makes the wife the central character of the lai. She is the source of both men’s desire throughout the tale and is the pivotal figure around whom all action revolves. At the beginning of the tale, the husband is defined only in terms of the wife’s qualities. Further, she is clever. Her cunning initially enables the lovers to conceal their love from her husband. Moreover, Glyn Burgess and Keith Busby note that the wife makes key decisions and takes the initiative at crucial moments in the lai.1 When her husband asks why she is always absent from their bed, she quickly devises the excuse for going to the window to meet her lover secretly. Later, it is she who reestablishes communication with her lover after they had been separated by wrapping up the dead bird and sending it to him with an explanation sewn into the samite wrap. With this gift, she initiates the creation of the memorial to their love. The author sympathizes with the wife’s plight as a victim of her husband’s violence and looks favorably on her choice of love over duty to her husband. In the end, Marie is the omniscient narrator but also the judge who decides in favor of the lady and her lover. _______ Marie de France, The Lais of Marie de France, trans. with an introduction by Glyn Burgess and Keith Busby (London: Penguin Books, 1999) 10. 1 2 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ The writer known since 1581 as Marie de France2 transformed a series of twelve Breton folk songs called lais into some of the most marvelous French courtly literature of the Middle Ages. Although details of her identity are unknown, she is universally considered to be the first female French poet.3 Marie does emphasize her French origins in her writing. In line four of the Epilogue of her Fables, she states, “My name is Marie, and I come From France” (“Marie ai num, si sui de France”),4 which may indicate that she worked in England, perhaps in the AngloNorman court of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in the second half of the twelfth century.5 The oldest copies of the lais are in the vast thirteenth-century Harley Manuscript in the British Library that contains all twelve lais and a fifty-six line prologue; three manuscripts with fewer lais are in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and another is in the British Library.6 The subject matter of the lais comes from la Matière de Bretagne (the Matter of Britain), one of the five sources of stories in French courtly literature, along with la Matière de France and la Matière d’antiquité about Thebes, Troy, and Rome. La Matière de Bretagne most notably includes the Arthurian legends. Marie does treat an Burgess and Busby write on page one of their introduction to The Lais of Marie de France that Claude Fauchet first used this name in his Recueil de l’origine de la langue et la poésie françoise (Paris, 1581, Book II, item 84). 2 For discussion of Marie’s identity, see Burgess and Busby’s introduction to The Lais of Marie de France or R. Howard Bloch’s The Anonymous Marie de France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). 3 4 Burgess and Busby 15. Eleanor’s support of the arts and her introduction of the lyric poetry of the troubadours from her southwestern French homeland to both northern France (through her first marriage to Louis VII) and England were driving forces in the development of the roman courtois from the epic chansons de geste. 5 The Old French version used in this essay is from the Harley Manuscript found in The Lais of Marie de France on pages 156-160. The English prose translation of this lai is by Glyn Burgess and Keith Busby in the same work on pages 94-96. 6 3 Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Arthurian subject in Lanval, but the other lais treat Breton subjects unrelated to this cycle. Marie transformed the lais into French verse using the traditional octosyllabic rhyming couplets of medieval romance. Although Marie’s lais have similar themes and conventions as romances, they are considerably shorter. Her two longest lais, Guigemar and Eliduc, that open and close the series in the Harley Manuscript, are much shorter than the romances of Marie’s near contemporary, Chrétien de Troyes. Nonetheless, the lengths of her lais vary. Burgess and Busby categorizes them as short (fewer than 400 lines), mid length (between 400-700 lines), or long (more than 700 lines).7 Six fall into the first category, four into the second, and two into the last. The average length is 477 lines. At 160 lines, Laustic is one of the shortest of the twelve lais. Only the episodic Chevrefoil is shorter at 118. Laustic’s brevity necessarily limits detailed description and means that the reader is missing information that could help interpretation. For example, the reasons for the bachelor’s pursuit of the wife are not fully developed. We do not know the background of the marriage whose problems are only apparent when the wife takes a lover. Nevertheless, Marie is still able to develop in just 160 lines a tale with complex characters and plot that takes place over a period of several months. The lai is dense, every word contributing meaning and nuance to the tale of deception, jealousy, violence, shattered love, and ultimately, spiritual love. She is able to create such a complete tale with so few lines because the lai has only three characters and is set in just two noble houses. Magic or the supernatural is often central to courtly romance and to other lais, but Laustic stands out for its realism. There are no fairies like in Lanval, no magic potions as in Les Deux Amanz, no shapeshifting animals or humans as in Yonec or Bisclavret. Further, God, who often figures in courtly literature on the side of the good nobles, is absent in this lai. By eliminating God and the supernatural and by focusing on a love triangle, she creates a purely secular and 7 Burgess and Busby 10 and 31. 4 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ domestic tale. Without the conflict between love and martial duty so often central in Chrétien’s romances, she further highlights the domestic. The nightingale was already a popular symbol in both classical literature and in the French troubadour love lyric by the time Marie was writing in the mid-twelfth century. In her treatment of the nightingale in medieval romance, Wendy Pfeffer states that the use of this bird was particularly popular in the twelfth century.8 As in a troubadour aubade, Marie’s nightingale is nocturnal and vanishes at dawn in the same way the lovers meet at night and must separate at sunrise. The nightingale can specifically symbolize physical love, which it does indirectly in this lai. Although they never actually make love, the wife does experience physical rapture at hearing her lover’s voice, which she compares to a nightingale’s song. The bird also symbolizes their love. Its joyful song comes to life because of summer’s bounty just as the couple’s love intensifies for the same reason. The bird’s exuberance in summer reflects their own uncontrolled joy, which leads to their downfall. The bird’s death means the end of their idyll. The killing of the nightingale also stands for the husband’s wish to kill the lover and/or his wife. The lovers’ creation that houses the dead bird both memorializes their affair and puts it back together in a new, more spiritual way. _______ In the first six lines, Marie introduces herself as the lai’s author, identifies the source of the tale, and then proceeds to highlight the literary and cultural transformations through which she puts it. By focusing on herself as both narrator and translator, she draws attention to role of the author as she does throughout the lais, most significantly in the fifty-six line prologue. She becomes part of the lai with the phrase “Une aventure vus dirai” Wendy Pfeffer, The Change of Philomel: The Nightingale in Medieval Literature. American University Studies III: Comparative Literature, Volume 14 (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1985). 8 5 Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ [v.1]. She informs the reader that she is relating a tale from Brittany known as Laustic and proceeds to give its French translation as rossignol to show the conversion of the tale from its original Breton to her own French. She then, for the only time in her lais, provides the English translation of the Breton title as nightingale. In that brief introduction, she emphasizes the international audience that her writing addresses. She is writing a Breton tale in French with an English reference that might prove that the author was writing in the francophone Anglo-Norman court. Further, the translation of this Breton tale into French is all the more compelling because its themes of foiled happiness, of failed noble ideals, and of redemption from flawed behavior were also recurring themes in the contemporary noble literature of France and Britain. Marie’s work defines translatio, in which both words and culture are transformed and adapted for another culture ready to accept them. In lines seven to twenty-two, Marie introduces the only three characters in the lai. They include a knight and his wife and a young knight who is a bachelor. They live in adjoining chateaus separated by a wall as in Ovid’s Pyramus and Thisbe.9 The author only relays what is said and thought about these characters. Later the reader can draw his or her own conclusions about them based on their actions. To the outside world, the characters shine and are the quintessential representatives of their class. The behavior of the two males so embodies noble ideals that they have brought renown to their entire town: “Pur la bunté des deus baruns / Fu de la vile bons li nuns” [v.11-12]. Although Marie never names the village, she lends it and the entire tale verisimilitude by saying that it is near the actual port of Saint Malo in Brittany. She then proceeds to detail each of the three characters. The first description is of the married knight. Curiously, Marie says nothing about his character. She only writes that he had “taken a…wife” (“Li uns aveit femme espusee” [v.13]), whom Marie then describes Ovid’s Metamorphoses was one of the most widely known classical texts in Marie’s time, and she is probably referencing it here and will do so again later. 9 6 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ formulaically as behaving according to the mandates of her class. Marie writes that she is “Sage, curteise e acemee/ a merveille se teneit chiere / Sulunc l’usage e la manere” [v. 14-16]. Marie only describes the husband through his wife. What are we to make of her silence? Only in retrospect can the reader surmise that Marie’s silence could hint at the husband’s lack of admirable traits. However, at this point in the lai, she uses metonymy to lead the reader to transfer the courtly qualities of the wife to the husband. In stark contrast to the husband’s nameless qualities, Marie reserves one of her only detailed descriptions in the lai for the bachelor, although it is, again, stock. He conforms perfectly to the definition of chivalry in courtly literature. She first focuses on the most important of a knight’s requisite skills. He is courageous and talented in the use of arms. She writes that he was “Bien coneü entre ses pers / De prüesce, de grant valur” [v. 18-19]. He also excels in his courtly manners: “E volunters feseit honur / Mut turnëot e despendeit / E bien donot ceo qu’il aveit” [v. 20-22]. Her description progresses logically from his martial to his social character, and, finally, in the next section, to his erotic behavior. From lines twenty-three to fifty-six, Marie sets the aventure in motion. She describes the lovers’ courtship and the development of the affair that they keep hidden through their discreet behavior. At this point, the lai moves from the characters’ lives in public to their lives in their own private world, into which Marie has a privileged view as omniscient narrator. Mary’s narrative technique shifts from reports about the nobles to descriptions and transcriptions of what they actually do and say. The reader must now judge the characters based on their actions behind closed doors. All three nobles are different from the public perception of them. The courtly ideals that they exemplify to those in the outside world who see them as models of noble qualities give way to demonstrations of uncontrolled passion, lies, jealousy, and violence. In the privacy of their own homes, they all betray the code of noble behavior in some way and are tarnished. Whether intended or not, Marie begins her description of the love affair with some irony. In line twenty-two, she finishes her 7 Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ glowing description of the bachelor as the ideal knight and continues in the next lines to describe his relentless pursuit of his neighbor’s wife. Instead of “giving generously whatever he had” as Burgess and Busby translate “E bien donot ceo qu’il aveit” from line twenty-two, the bachelor now takes whatever he wants. Conforming to patterns of courtly literature, the nobleman pursues the noblewoman. Curiously, however, Marie does not clearly specify the reasons for the knight’s attraction to the woman, as she does in her other lais treating adultery. She only states that he fell in love with her and successfully pursues her by relying on persistence, prayer, and his admirable qualities: “La femme sun veisin ama; / Tant la requist, tant la preia / E tant par ot en lui grant bien” [23-25]. Marie does specify why the wife surrenders to the bachelor’s request for her love. She has heard good things about him; plus he lives next door. Those qualities so thoroughly detailed by Marie just a few lines previously that describe him as the ideal noble make him attractive to the wife: “E tant par ot en lui grant bien / Que ela l’ama sur tute rien / Tant pur le bien quë ele oï / Tant pur ceo qu’il iert pres de li” [v. 2528]. She is swayed by what she has heard and by what she has seen, two of the standard reasons for falling in love in courtly literature. This is, however, not an affair of passion that has been simmering across fences, has been kept in check, but can no longer be controlled. Among all the affairs in Marie’s lais, this one seems to have the most mundane origin, born out of convenience, the bachelor’s persistence, and the wife’s boredom with her husband, whose nameless qualities do not match those of the exciting young bachelor. Marie’s irony shines through again as she finishes the section that describes the beginning of their affair. The wife is hardly conducting herself, as was stated earlier in line sixteen, “Sulunc l’usage e la manere” of noble courtesy. Although the original reasons for their mutual attraction may be mundane, their love for each other does become strong and true. Perhaps Marie emphasizes the banal origins of the affair to juxtapose it to the intense love that develops. Marie’s description of the joy that their love brings is so positive that she clearly 8 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ condones their behavior. They play their love out day and night through looks, words, and gifts exchanged through their windows in their neighboring mansions. In line twenty-nine, she emphasizes the wife’s wisdom, using the word “wisely’ (“sagement”) to describe how they conduct their affair so that they are able to conceal it from her husband. Earlier in line fourteen, Marie had also described the wife as “wise” whose use was more conventional, meaning to behave moderately. In this second use in line twenty-nine, Marie shows that the wife’s wisdom is not defined as propriety but as cunning. Nonetheless, both kinds of wisdom reflect the wife’s mesure, the Old French term for moderation, the trait so highly prized in medieval literature. Because of their mesure, they keep their affair hidden, and it can continue. The first description of the husband’s actions reveals that he is protective and suspicious of his wife. He has her supervised so that she and the bachelor are never alone and cannot consummate their love. Clearly, they would like to and give no thought to their marital or chivalric duty. The husband, however, has taken precautions to prevent his wife from straying: “N’unt gueres rien que lur despleise / Mut esteient amdui a eise / Fors tant k’il ne poënt venire / Del tut ensemble a lur pleisir / Kar la dame ert estreit gardee / Quant cil esteit en la cuntree” [v. 45-50]. The aventure takes a turn in line fifty-eight when, for the only time in the lai, Marie describes the weather and its effects. The fecundity of summer stimulates the lovers’ passion. It is a force of nature that influences them, and they act recklessly. They constantly go to their windows at night to speak to each other. Her earlier mesure gives way to démesure, and their affair is exposed: “Lingement se sunt entramé? Tant que ceo vient a un esté / Que bruil e pre sunt reverdi / E li vergier ierent fluri. Cil oiselet par grant duçur / Mainent lur joie en sum la flur. Ki amur as a sun talent / N’est merveille s’il i entent” [58-64]. At this point, the field of characters and the setting narrow further as the action moves into the couple’s mansion. Her frequent absence from bed angers her husband, and he demands 9 Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ to know the reason for it. The wife quickly invents a plausible excuse. Unwittingly however, she dooms their love with this ruse.10 She explains that the nightingale’s song in the night wakes her up, but its song is so beautiful and gives such pleasure that she must listen to it. Her words are pure double entendre. Each time she refers to the “song of the nightingale” to her husband, she is replacing those words in her own mind with “lover’s voice.” This is the first instance in the lai in which the wife speaks directly to her husband. The wife’s first words to her husband are lies for which she feels no shame. Because it is a direct address, the lie lays open the deceit even more powerfully: “‘Sire’, le dame li respunt / ‘Il nen ad joië en cest mund / Ki n’ot la laüstic chanter / Pur ceo me vois ici ester / Tant ducement l’I oi la nuit / Que mut me semble grant deduit / Tant me delit e tant le voil / Que jeo ne puis dormir de l’oil’” [v 83-90]. Her experience at the window is so powerful that it puts her in a state of physical rapture. Marie clearly believes that the joy that such powerful emotion brings outweighs the deception. Her answer rankles the protective husband who is indifferent to the song’s beauty, jealous of its place in his wife’s life, and suspicious of her behavior. In lines 91-110, he plans his revenge against his wife by first trapping the bird: “Quant li sires ot que ele dist/De ire e de maltalent en rist / De une chose se purpensa / Le laüstic enginnera” [v. 91-94]. Just as her excuse for her absence couched her true meaning, the ostensible reason for capturing the nightingale also conceals his real intention. His stated reason for trapping the bird appears honorable; he captures it so that it will no longer disturb the wife’s sleep. His real intention is to prevent her from having a reason to go to the window. As with the wife, the husband’s first direct quote to his partner also conceals his real meaning: “‘Dame’, fet il, ‘u estes vus? / Venez avant, parlez a nus! Bloch states that the lais are Marie’s “articulation of the fatal effects of language” whereas her Espurgatoire shows that language is “a means to salvation” (21). 10 10 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ / J’ai le laüstic englué/Pur quei vus avez tant veillé / Desor poëz gisir en peis / Il ne vus esveillerat meis’” [v.105-110]. Starting in line 111, the husband’s brutal behavior directed at his wife is the climax of the lai. He first refuses her pleas to save the bird and then wrenches off its head in front of her and throws the bloody body at her breast, staining her dress. He purposefully targets her breast because it symbolizes the love that she denies him that she offers the young bachelor. Behind closed doors, the husband betrays the code of chivalric behavior for which he was lauded in public. He does to the bird what he would like to do to the intruding bachelor and perhaps to his wife. Earlier, in lines eighty-three to ninety, the wife craftily talked about the “nightingale’s voice” to her husband as she replaced those words with “lover’s voice” in her own mind. The death of the nightingale’s song is now also the death of the lover’s voice and the joy that it brought. By killing the bird, the husband has accomplished the task he had set out to do. He ends the affair between the wife and the bachelor because the wife no longer has the excuse for leaving the marital bed. At the same time, his actions have another consequence that he perhaps did not intend or perhaps to which he is indifferent. His ugly behavior destroys any relation he had with his wife. The husband’s disappearance from the rest of the narration reflects his disappearance from his wife’s life. His disappearance also prevents any redemption for his loutish behavior. The stain on her dress stands for the stain on his honor that is not rectified. However, the wife and her lover do have the opportunity to redeem themselves from their imperfect behavior. The wife realizes that the bachelor does not know what has happened and devises a way to reestablish communication with him. She beautifully wraps up the dead bird in samite and sends it to him with a note of explanation woven into the cloth.11 Monica L. Marie is probably referencing the scene in Ovid’s Metamorphoses in which Philomila weaves images of her sad tale and sends it to her sister Procne. Philomila is the object of Tereus’ violence just as the wife suffers that of her husband in this lai. 11 11 Marie de France’s Lai du Laustic ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Wright has stated that samite was exquisite, richly decorated silk that was technically challenging to make. It was greatly sought after but difficult to obtain because it was commercially unavailable. It was part of the medieval gift economy among those at the most rarified levels of society and was often given to churches.12 The lover builds a vessel also made of precious materials to house the bird, and he will carry it with him forever. Both lovers’ careful treatment of the bird indicates the importance that each feels about the love they shared. The bejeweled case refers to both the past and to the future. It memorializes the joy that they shared that the husband can never stifle. Although they are destined to be forever separated, the case keeps their love alive and saves it, it some way, from being an unattained quest. Their creation also puts back together what has been shattered by the husband and signals the birth of a different kind of love. In his translation of the lais into modern French, Philippe Walter states that the case resembles a reliquary.13 It thereby takes on a religious nature. Because samite was often given to churches, the use of this material inside the case adds to its sacred quality. Their love therefore takes on a holy dimension, and the lovers transform their erotic love into spiritual love. The lovers’ combined actions at the end of the tale conform closely but not perfectly to the definition of courtly love. The knight’s creation makes him worthy of the love of his mistress. Although she never sees the case and cannot confer her love on him, she did initiate the action that led to their redemption. They therefore restore their noble character that had been sullied by their earlier actions. By living up to the ideals of courtly love, the lovers come full circle to the lai’s beginning. Yet the The description of samite is based on a presentation for the International Courtly Literature Society entitled “Superlative Silk: Samite in Medieval French Romances” by Monica L. Wright of Middle Tennessee State University at the 2006 South Central Modern Language Association conference at the Renaissance Hotel in Dallas, October 28, 2006. 12 13Marie de France: Lais, trans. Philippe Walter (Paris: Gallimard, 2000) 468. 12 Stuart McClintock ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ noble behavior at the beginning is different from that at the end. Initially, the three characters’ nobility is defined in terms of their conforming to the rituals of their class that they act out in public. In the end, the actions of the lovers stem from their purity of heart. Marie contrasts two different definitions of noble behavior: actions based on depth of emotion and actions based on external codes of behavior. As she does in several other lais, Marie sides with the lovers despite their deception because their love is more important than conformity to codes of behavior. Midwestern State University 13