The Politics of Virginity: Abstinence in Sex Education

By Alesha E. Doan & Jean Calterone Williams

Reviewed by Jessica Zietz

I. INTRODUCTION

The Politics of Virginity provides a detailed examination of abstinence-only

education in American public schools. The authors argue that abstinence education is

scientifically inaccurate, out-of-step with parental preferences, and dangerous to

adolescents. They carefully trace the history of abstinence education’s “stealth”

introduction into public schools and study the content of four widely used abstinence

textbooks, noting how the curricula perpetuate misinformation and harmful gender

stereotypes. Throughout the book, both the macro and micro effects of abstinence

education are examined. Numerous studies support the authors’ arguments against this

form of sex education, while interviews with 32 teenage women provide poignant insight

into the real-life effects of these policies. The rise of abstinence education presents a

modern day example of the Galileo story. Despite overwhelming evidence that

comprehensive sex education is the most effective approach for teenagers, a small,

religious minority has succeeded in implementing abstinence policies in a third of public

schools. Parental voices are ignored, real science labeled junk. While not an explicit

focus like it was in Galileo’s time, religion is implicitly used as a justification for policy

decisions in secular schools. A population undoubtedly in need of truthful information is

lied to under the guise of protection. These recurring themes present a world not so

different from Galileo’s.

II. STEALTH MORALITY POLICY

1

The Politics of Virginity begins with an introduction of one of the book’s most

frequently used phrases: “stealth tactics in morality policy.” The authors explain that

“morality policies tend to address such issues as gay marriage, abortion, and like policy

areas where the locus of the conflict is moral, not material. Advocates of morality

policies wish to create change, largely through moral persuasion and policies regulation

behavior.” (1). While abortion and same-sex marriage opponents have been become

increasingly vocal, abstinence advocates have used a different tactic, one the authors term

“stealth morality policy.” This policy “mirrors omnibus legislative strategies used in

nonmorality policy areas. . . . and may allow an unpopular policy, or a policy supported

by a well-organized minority, to be passed legislatively without having to undergo much

legislative debate or public scrutiny.” (1). Morality policies aim to simplify a debate by

labeling the other side morally wrong; “[c]laiming that abstinence until marriage is the

only acceptable choice because it is the only moral choice leaves little room discussion or

compromise on the content of sex education. Any sexual activity outside of marriage is

considered detrimental. . . .” (11).

III. THE RISE OF ABSTINENCE-ONLY EDUCATION

In the first two chapters, the authors provide a historical context for the stealth

rise of abstinence education, tracing the introduction of sex education in schools to the

advent of the birth control pill. The arrival of the pill, combined with “liberalization of

contraception and abortion laws” in the 1960s and early ‘70s had two relevant effects: a

decline in unwanted pregnancies in adult women and a rise in pregnancies among unwed

teenage women. (25). Congress responded in part by adding Title X to the Public Health

Service Act, providing funds for family planning services and education. (26). The

2

federal government, however, did not press for sex education in public schools. Instead,

many schools implemented these programs on their own. The content was

straightforward, focusing mostly on “physical and sexual development, sexually

transmitted disease prevention, and contraceptive use.” (26). While the curricula were

competently designed to address very real problems, schools were met with fervent

opposition by the Christian right, particularly Evangelical Christians. This segment of the

population, note the authors, is “much more inclined than the general population to

believe premarital sex [is] immoral. . . . [and] leads to harmful psychological and

emotional consequences for the unwed compared to other Americans.” (26). Evangelical

groups fought against sex education, contending it violated parental rights and subverted

Christian morality. However, by the 1980s, these groups realized that their push to

eliminate sex education was futile. “Rather than concede defeat, Christian conservatives

adopted a new strategy: restructuring the content of sex education.” (27). Thus, the focus

was shifted from elimination to replacement, and abstinence-only education was born.

Abstinence education supporters tirelessly lobbied politicians, gained support for

their agenda, and claimed their first victory in 1981 when the Adolescent Family Life Act

(AFLA) replaced the Adolescent Health Services and Pregnancy Prevention Care Act.

The bill was carefully designed to attract bipartisan support; it included as a compromise

“a statute that designated the bulk of the money . . . to support services for pregnant and

parenting teens.” (28). AFLA was “quietly” included in the Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act of 1981 and signed into law “without drawing hearings or floor

votes.” Id. However, over the years, Congress failed to provide broad support for the

Act. Further action was needed.

3

Legislatively, the most significant development for abstinence education came

with the passage of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity

Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). The Christian Right strongly opposed welfare, arguing

that it “undermined the traditional family by contributing to the rise in female, singleheaded households.” (29). If young women could be depend on government support,

they reasoned, a husband was no longer a necessity. President Clinton promised welfare

reform through a focus on job training and assistance with necessities such as child care;

conservatives, on the other hand, aimed to “reduce federal spending through a variety of

radical measures,” including “prohibiting the allocation of welfare checks to children

born to unwed teenage mothers. . . .” (30). When Republicans retook the House of

Representatives in 1996, they “cast welfare as the root cause of dysfunctional families”

and sought to “compassionately” eliminate the path to this destruction. (31). The GOP’s

bill was debated extensively; however, “abstinence-only education was never presented

to Congress, or the general public, as a solution to illegitimacy, poverty, or welfare

abuse.” Id. Instead, conservatives used stealth tactics to include funding for an

abstinence education program, labeled Title V, in the miscellaneous provisions of the

final bill. Id. President Clinton signed the bill into law, while noting that “serious

problems remain[ed] in the non-welfare provisions of the bill.” (33). As a result, from

1997-2006, Title V received $875 million in funding. (40).

Abstinence-only advocates used another stealth tactic to implement their policies.

Recognizing that the content of many sex education programs is decided at the local

level, religious conservatives ran for school board positions. However, they normally did

4

not disclose their status as Christian conservatives or their abstinence agenda until after

their elections. (29-30).

Abstinence-only education joins two other primary forms of sex education in the

United States. Comprehensive sex education, the least common method, teaches “a

broad curriculum that incorporates sexual development and physiology, reproductive

health,” pregnancy, STD prevention, and birth control methods that include abstinence.

(45-46). Abstinence-based education also discusses reproductive health issues, and

provides a limited discussion on birth control methods and condom usage. Id.

Abstinence-only education, on the other hand, “either bans communication about

contraception or allows it only in the framework of contraceptive failure rates.” Id.1

IV. ABSTINENCE CURRICULA’S DEFINITIONS OF YOUNG WOMEN

The authors devote the book’s third chapter to competing cultural definitions of

young women’s sexuality. The chapter’s title, “Good Girls” or “Dirty Whores”?, sums

up the religious right’s two extreme views of women—views on each end of a spectrum

that leave little room for anything in the middle. Adolescent girls are pure and innocent,

and must be protected from information that would corrupt them. Their virginity is a

treasure that must be carefully guarded, and then given as a gift to a worthy husband. If

women fail in this noble mission, they are deviant and shameful. Simultaneously,

however, women are innate temptresses who must avoid enticing men. A skimpy outfit

or goodnight kiss will provoke an uncontrollable urge in a young man; if he acts on it, the

woman is at least partially responsible. Abstinence education reinforces these harmful

views in a myriad of ways. A later chapter provides excerpts from four widely used

1

For the purposes of this review, the phrase abstinence education will refer to the stricter

abstinence-only education.

5

abstinence textbooks. One text warns that “[d]eep down, you know that your friend’s

plunging neckline and short skirts are getting the guys to talk about her. Is that what you

want? To see girls who drive guys’ hormones when a guy is trying to see her as a

friend?” (109 (quoting Sex Respect)).

V. SCIENTIFIC PROOF, AND LACK THEREOF

The book’s fourth chapter provides an assessment of abstinence-only curricula.

Statistics and studies, however, are found throughout the entire book. Numbers and

charts make the book feel dry and clinical at times; however, they are arguably the book’s

most crucial component. They provide indisputable scientific support to the authors’

cause, something of which Galileo was in dire need. Langford criticized Galileo for

expecting the Church to believe his conclusions when he simply did not have enough

proof. Here, however, there is no logical, provable counter to the myriad of scientific

evidence that disproves abstinence education’s efficacy. (There are, however, plenty of

illogical responses. For example, a Harvard University study concluded that over half of

adolescents who made virginity pledges “denied taking the pledges when asked about it a

year later. Many of the teens that denied ever taking pledges had become sexually

active.” The study, which was published in the peer-reviewed American Journal of

Public Health, was dismissed by abstinence supporters as “junk science.” (13).)

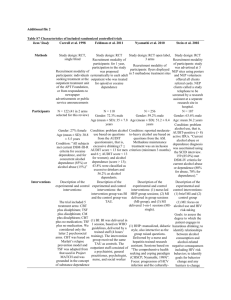

A sampling of the many studies cited is sufficient to summarize the authors’

points. First, while “[m]any adults may not approve of adolescent sexual activity. . . .

[d]epending on the specific issue, 84 to 98 percent of parents want their children to be

taught about contraception, pregnancy,” STDs, and abortion. (7). Second, teens possess

worrisome misconceptions: “around 20 percent of teens do not think condoms are

6

effective in preventing HIV/AIDS and STI transmission, and one in five teens

erroneously believe birth control pills provide protection against sexually transmitted

diseases.” (117). Most significantly, abstinence-only education has not reached its goals

of eliminating or even reducing sexual activity in teenagers. Statewide evaluations of 11

abstinence-only programs found that, while abstinence-only education programs were

“most successful at improving participants’ attitudes towards abstinence,” they were

“least likely to positively affect participants’ sexual behaviors.” (47). Put simply,

changes in attitudes have not led to changes in behavior. Another study found that, after

completing abstinence-only programs, “there were no differences among the students

who had received abstinence-only instruction and those who had not on important

measures of sexual behavior.” (48). The authors describe the reliable methodology used

in each study, such as use of control groups, surveying both groups over a four to six year

period, and following up with both groups years later. These methods are then contrasted

with the inaccurate “research” cited by abstinence advocates. For instance, one

abstinence texts states that “only 5 to 21 percent of couples use condoms consistently and

correctly, and . . . even with correct usage, condoms do little protect against disease.”

(117). The authors retort that “[d]ownplaying the efficacy of condoms runs contrary to

vast scientific research indicating the opposite: Consistent condom use is an effective

method for reducing the risk of infection contraction and transmission.” Id. Questionable

research methods are highlighted most clearly in a section on one textbook’s discussion

of abortion. The book, Sexuality, Commitment, and Family (SCF), states that pregnant

women who choose abortion experience chronic grief, suicidal thoughts and attempts,

heavy drinking, and nightmares. (118). Shockingly, it claims that women who terminate

7

a pregnancy are more likely to abuse subsequent children. These claims have no

scientific support. They are traced to a book on abortion written not by a scholar, doctor,

or academic, but by a pro-life advocate. He came up with his “findings” by actively

seeking out a small number of women who regretted their abortions. The women were

“not representative of the general population of women who have had abortions, so basis

a study on their perspectives does not yield unbiased information that can be used to

make general claims about women who have had abortions.” (119). Yet the information

is treated as scientific and unbiased, both in the original book and the textbook repeating

the findings. Readers of SCF have no way of knowing where the information comes

from or that it is misleading and unreliable. This is precisely the type of “research” used

to support abstinence-only programs.

VI. STEALTH INCLUSION OF RELIGION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Christianity formed the basis of opposition to Galileo’s heliocentric findings.

Similarly, opposition to sex education has its root in religion. Religious conservatives are

aware that they can’t successfully push for Bible passages in public school abstinence

texts. But, in yet another example of stealth tactics, Christianity is used implicitly in

abstinence curricula. For example, one text, Sex Respect, refers to men as heroes and

women as helpmates. “The biblical notion of woman as helper,” note Doan and

Williams, is “taken from the introduction of Adam and Eve in Genesis. . . .” SCF,

meanwhile, states that life begins at conception and abortion kills the unborn—religious

concepts firmly supported by Evangelical Christians. These statements are misleadingly

treated as scientific fact, rather than religious doctrine.

VII. ABSTINENCE-ONLY EDUCATION IN PRACTICE

8

The book tempers its dry statistics with stories of young women navigating sexual

activity and peer pressure with little to no guidance from schools and parents. The focus

is on minority women from low-income families—precisely the group conservatives

sought to “compassionately assist” through welfare reform and abstinence education.

The women’s experiences are often heartbreaking; many were pressured into sex at

young ages and, due to lack of education, did not protect themselves against pregnancy

and STDs. Some had been sexually assaulted. Most felt they lacked the confidence or

capability to firmly resist pressure from men; if they didn’t loudly yell “no,” they

reasoned, they hadn’t really been raped. Women who ended up pregnant felt they

deserved it, even though they had often (unsuccessfully) asked their partners to use

condoms or their parents to help them obtain birth control. The stories highlight the

complexity of adolescent female sexuality, concluding that black-and-white, oversimplified abstinence education does little to address the many struggles of, and

influences on, these women. The focus is on young women, because the authors believe

that abstinence texts are geared most toward women; it is women who are given the

responsibility for controlling themselves so they don’t tempt men.

VII. CONCLUSION

The Politics of Virginity provides a damning assessment of abstinence-only

education in America. At the same time, however, one wonders if 200 pages of facts and

stories and public opinion polls and studies do any good when the opposition can brush

off any study as junk science, any story as deviancy. Langford seemed firm in his belief

that, with enough proof, the Church would have accepted Galileo’s findings; hundreds of

years later, though, proof hasn’t stopped religious conservatives from avidly supporting a

9

policy shown to be wrong in so many facets. Whether abstinence education receives

funding and support appears to depend on which political party controls Congress, rather

than on the truth and efficacy, or lack thereof, of these programs. Recognizing this

dilemma, the authors note that, even though support for abstinence education has waned

in recent years, “it is unlikely to disappear in the near future.” (170). This pessimistic

outlook acknowledges the reality that, even in the 21st century, science can still be

contested in the name of religion.

10