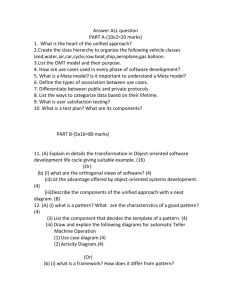

AN OBJECT-ORIENTED FRAMEWORK

advertisement