Julie Fairman, Making Room in the Clinic: Nurse Practitioners and

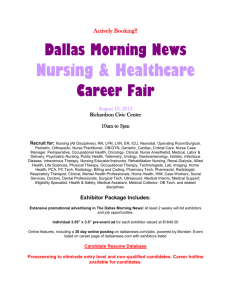

advertisement

Julie Fairman, Making Room in the Clinic: Nurse Practitioners and the Evolution of Modern Health Care (New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 2008) A revolution was taking place in US healthcare during the 1960s and 70s. A shortage of physicians, particularly in deprived and rural areas, coinciding, with a dramatic and rapid advance in the development of nursing skills and knowledge, led to a seismic shift in professional boundaries. The result was the emergence of the ‘nurse practitioner’: a completely new type of nurse. The role developed slowly at first, as a necessary response to patient need, and then gained momentum as governments and policy-makers came to recognise its value and cost-effectiveness. Complex as it was, the real nature of the nurse-practitioner movement has, until recently, been difficult to define and trace. Its development has been shadowed in uncertainty and controversy, and it is for this reason that Julie Fairman’s lucid and detailed history is such a welcome contribution to historical scholarship. Meticulously researched (using both archive sources and oral history interviews) and convincingly argued, Fairman’s book is admirable in its willingness to tackle some of the more complex and difficult aspects of the history of the nurse practitioner. The author demonstrates how important the initial grass-roots development of the movement was, showing how individual nurse-physician partnerships experimented with the shifting boundaries between a medical profession which was becoming increasingly hard-pressed in some of its less popular and lucrative areas of practice, and a nursing profession which was, for the first time, asserting its rapidly-growing knowledge and clinical prowess. Fairman also draws our attention to some of the most impressive academic partnerships of the mid century, notably those of Dorothy Smith and George Harrell at the University of Florida, and Joan Lynaugh and Barbara Bates, at the University of Rochester. When she moves to a consideration of how the nascent nurse-practitioner movement began to cohere as a nation-wide health care reform, Fairman leads us adeptly through the confusing turf-wars of mid-twentieth-century healthcare. She avoids generalisations, demonstrating instead how some physicians supported and nurtured the developing movement, whilst others were, at times, destructive in their opposition. The book analyses the nature of the difficult and sometimes dangerous ‘borderlands’ between medicine and nursing demonstrating its author’s consummate skill as a historian capable of uncovering the finest detail without losing sight of the larger picture. One of the most important sections of the book is that which offers an interpretation of the relationship between physicians’ assistants and nurse practitioners which is based firmly in an analysis of mid-to-late-twentieth-century gender-relations. Physicians assistants, who were mostly male and nurse-practitioners, who were mostly female, found it difficult to negotiate their roles within the ‘borderland’ territories between nursing and medicine. Fairman offers the reader clarity by demonstrating how different the motivations of the two groups were: physician’s assistants aiming to practise a ‘lesser’ form of medicine, whilst nurse- practitioners saw themselves asserting the breadth of nursing practice, moving comfortably into areas of natural overlap between their own profession and that of medicine. 1 Finally, the book offers an important analysis of the political context of the nursepractitioner movement, tracing the ways in which federal governments dealt (more or less successfully) with the complexities of mid-to-late-century shifts in healthcare boundaries, and analysing the sometimes-disappointing responses of professional organisations to the emergence of the new nursing roles. Fairman draws our attention, in particular, to how difficult it was for the American Nurses’ Organisation to free itself from its prevailing preconceptions about the boundaries of nursing work in order that it could support the newly-emerging practitioners. The reader is left in no doubt that it was not the leaders of the profession but a thriving grass-roots movement that drove forward the reforms of the mid-century. I would commend Julie Fairman’s carefully-researched and eminently readable book not only to nurse-historians, but also to anyone interested in the development of postwar healthcare in the USA, or in political, economic and social change during the later decades of the twentieth century. Above all, this readable text offers us insights into the ways in which nurses were able to break free of pre-existing constraints in order to demonstrate that they were not (and, in fact, never had been) merely operatives who carried out ‘medical orders’. Their skills- and knowledge-base, their underlying education and their capacity for astute clinical judgement, made them the independent, autonomous practitioners at the apex of a rapidly developing healthcare world. Christine E. Hallett 2