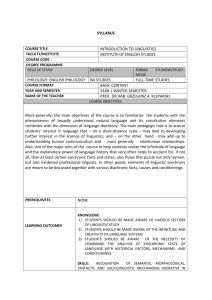

The Object of Study

advertisement

Readings

Chapter 1 Invitation to Linguistics

Table of Contents

Text 1. The Object of Study (Saussure)

Text 2. Language as Social Semiotic (Halliday)

Text 3. Knowledge of Language as a Focus of Inquiry(Chomsky)

Text 4. The Domain of Linguistics: An Overview(Geoff Nunberg and Tom Wasow)

Text 5. Why Major in Linguistics?(Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett)

Text 1

The Object of Study

1. On defining a language

What is it that linguistics sets out to analyse? What is the actual object of study in

its entirety? The question is a particularly difficult one. We shall see why later. First,

let us simply try to grasp the nature of the difficulty.

Other sciences are provided with objects of study given in advance, which are then

examined from different points of view. Nothing like that is the case in linguistics.

Suppose someone pronounces the French word nu ('naked'). At first sight, one might

think this would be an example of an independently given linguistic object. But more

careful consideration reveals a series of three or four quite different things, depending

on the viewpoint adopted. There is a sound, there is the expression of an idea, there is

a derivative of Latin nudum, and so on. The object is not given in advance of the

viewpoint: far from it. Rather, one might say that it is the viewpoint adopted which

creates the object. Furthermore, there is nothing to tell us in advance whether one of

these ways of looking at it is prior to or superior to any of the others.

Whichever viewpoint is adopted, moreover, linguistic phenomena always present

two complementary facets, each depending on the other. For example:

(1) The ear perceives articulated syllables as auditory impressions. But the sounds

in question would not exist without the vocal organs. There would be no n, for

instance, without these two complementary aspects to it. So one cannot equate the

language simply with what the ear hears. One cannot divorce what is heard from oral

articulation. Nor, on the other hand, can one specify the relevant movements of the

vocal organs without reference to the corresponding auditory impression.

(2) But even if we ignored this phonetic duality, would language then be

reducible to phonetic facts? No. Speech sounds are only the instrument of thought,

and have no independent existence. Here another complementarity emerges, and one

of great importance. A sound, itself a complex auditory-articulatory unit, in turn

combines with an idea to form another complex unit, both physiologically and

psychologically. Nor is this all.

(3) Language has an individual aspect and a social aspect. One is not conceivable

without the other. Furthermore:

(4) Language at any given time involves an established system and an evolution.

At any given time, it is an institution in the present and a product of the past. At first

sight, it looks very easy to distinguish between the system and its history, between

what it is and what it was. In reality, the connexion between the two is so close that it

is hard to separate them. Would matters be simplified if one considered the

ontogenesis of linguistic phenomena, beginning with a study of children's language,

for example? No. It is quite illusory to believe that where language is concerned the

problem of origins is any different from the problem of permanent conditions. There

is no way out of the circle.

So however we approach the question, no one object of linguistic study emerges of

its own accord. Whichever way we turn, the same dilemma confronts us. Either we

tackle each problem on one front only, and risk failing to take into account the

dualities mentioned above: or else we seem committed to trying to study language in

several ways simultaneously, in which case the object of study becomes a muddle of

disparate, unconnected things. By proceeding thus one opens the door to various

sciences ―psychology, anthropology, prescriptive grammar, philology, and so on ―

which are to be distinguished from linguistics. These sciences could lay claim to

language as falling in their domain; but their methods are not the ones that are needed.

One solution only, in our view, resolves all these difficulties. The linguist must take

the study of linguistic structure his primary concern, and relate all other

manifestations of language to it. Indeed, amid so many dualities, linguistic structure

seems to be the one thing that is independently definable and provides something our

minds can satisfactorily grasp.

What, then, is linguistic structure? It is not, in our opinion, simply the same thing as

language. Linguistic structure is only one part of language, even though it is an

essential part. The structure of a language is a social product of our language faculty.

At the same time, it is also a body of necessary conventions adopted by society to

enable members of society to use their language faculty. Language in its entirety has

many different and disparate aspects. It lies astride the boundaries separating various

domains. It is at the same time physical, physiological and psychological. It belongs

both to the individual and to society. No classification of human phenomena provides

any single place for it, because language as such has no discernible unity.

A language as a structured system, on the contrary, is both a self-contained whole

and a principle of classification. As soon as we give linguistic structure pride of place

among the facts of language, we introduce a natural order into an aggregate which

lends itself to no other classification.

It might be objected to this principle of classification that our use of language

depends on a faculty endowed by nature: whereas language systems are acquired and

conventional, and so ought to be subordinated to―instead of being given priority

over―our natural ability.

To this objection one might reply as follows.

First, it has not been established that the function of language, as manifested in

speech, is entirely natural: that is to say, it is not clear that our vocal apparatus is

made for speaking as our legs for walking. Linguists are by no means in agreement on

this issue. Whitney, for instance, who regards languages as social institutions on

exactly the same footing as all other social institutions, holds it to be a matter of

chance or mere convenience that it is our vocal apparatus we use for linguistic

purposes. Man, in his view, might well have chosen to use gestures, thus substituting

visual images for sound patterns. Whitney's is doubtless too extreme a position. For

languages are not in all respects similar to other social institutions. Moreover,

Whitney goes too far when he says that the selection of the vocal apparatus for

language was accidental. For it was in some measure imposed upon us by Nature. But

the American linguist is right about the essential point: the language we use is a

convention, and it makes no difference what exactly the nature of the agreed sign is.

The question of the vocal apparatus is thus a secondary one as far as the problem of

language is concerned.

This idea gains support from the notion of language articulation. In Latin, the word

articulus means 'member, part, subdivision in a sequence of things'. As regards

language, articulation may refer to the division of the chain of speech into syllables,

or to the division of the chain of meanings into meaningful units. It is in this sense

that one speaks in German of gegliederte Sprache. On the basis of this second

interpretation, one may say that it is not spoken language which is natural to man, but

the faculty of constructing a language, i.e. a system of distinct signs corresponding to

distinct ideas.

Broca discovered that the faculty of speech is localised in the third frontal

convolution of the left hemisphere of the brain. This fact has been seized upon to

justify regarding language as a natural endowment. But the same localisation is

known to hold for everything connected with language, including writing. Thus what

seems to be indicated, when we take into consideration also the evidence from various

forms of aphasia due to lesions in the centres of localisation I is: (1) that the various

disorders which affect spoken language are interconnected in many ways with

disorders affecting written language, and (2) that in all cases of aphasia or agraphia

what is affected is not so much the ability to utter or inscribe this or that, but the

ability to produce in any given mode signs corresponding to normal language. All this

leads us to believe that, over and above the functioning of the various organs, there

exists a more general faculty governing signs, which may be regarded as the linguistic

faculty par excellence. So by a different route we are once again led to the same

conclusion.

Finally, in support of giving linguistic structure pride of place in our study of

language, there is this argument: that, whether natural or not, the faculty of

articulating words is put to use only by means of the linguistic instrument created and

provided by society. Therefore it is no absurdity to say that it is linguistic structure

which gives language what unity it has.

2. Linguistic structure: its place among the facts of language

In order to identify what role linguistic structure plays within the totality of

language, we must consider the individual act of speech and trace what takes place in

the speech circuit. This act requires at least two individuals: without this minimum the

circuit would not be complete. Suppose, then, we have two people, A and B, talking to

each other:

The starting point of the circuit is in the brain of one individual, for instance A,

where facts of consciousness which we shall call concepts are associated with

representations of linguistic signs or sound patterns by means of which they may be

expressed. Let us suppose that a given concept triggers in the brain a corresponding

sound pattern. This is an entirely psychological phenomenon, followed in turn by a

physiological process: the brain transmits to the organs of phonation an impulse

corresponding to the pattern. Then sound waves are sent from A's mouth to B's ear: a

purely physical process. Next, the circuit continues in B in the opposite order: from

ear to brain, the physiological transmission of the sound pattern; in the brain, the

psychological association of this pattern with the corresponding concept. If B speaks

in turn, this new act will pursue ―from his brain to A's ―exactly the same course as

the first, passing through the same successive phases, which we may represent as

follows:

This analysis makes no claim to be complete. One could go on to distinguish the

auditory sensation itself, the identification of that sensation with the latent sound

pattern, the patterns of muscular movement associated with phonation, and so on. We

have included only those elements considered essential; but our schematisation en-

ables us straight away to separate the parts which are physical (sound waves) from

those which are physiological (phonation and hearing) and those which are

psychological (the sound patterns of words and the concepts). It is particularly

important to note that the sound patterns of the words are not to be confused with

actual sounds. The word patterns are psychological, just as the concepts associated

with them are.

The circuit as here represented may be further divided:

(a) into an external part (sound vibrations passing from mouth to ear) and an

internal part (comprising all the rest);

(b) into a psychological and a non-psychological part, the latter comprising both

the physiological facts localised in the organs and the physical facts external to the

individual; and

(c) into an active part and a passive part, the former comprising everything which

goes from the association centre of one individual to the ear of the other, and the latter

comprising everything which goes from an individual's ear to his own association

centre.

Finally, in the psychological part localised in the brain, one may call everything

which is active 'executive' (c → s), and everything which is passive 'receptive' (s →

c).

In addition, one must allow for a faculty of association and coordination which

comes into operation as soon as one goes beyond individual signs in isolation. It is

this faculty which plays the major role in the organisation of the language as a system.

But in order to understand this role, one must leave the individual act, which is

merely language in embryo, and proceed to consider the social phenomenon.

All the individuals linguistically linked in this manner will establish among

themselves a kind of mean; all of them will reproduce ―doubtless not exactly, but

approximately ― the same signs linked to the same concepts.

What is the origin of this social crystallisation? Which of the parts of the circuit is

involved? For it is very probable that not all of them are equally relevant.

The physical part of the circuit can be dismissed from consideration straight away.

When we hear a language we do not know being spoken, we hear the sounds but we

cannot enter into the social reality of what is happening, because of our failure to

comprehend.

The psychological part of the circuit is not involved in its entirety either. The

executive side of it plays no part, for execution is never carried out by the collectivity:

it is always individual, and the individual is always master of it. This is what we shall

designate by the term speech.

The individual's receptive and co-ordinating faculties build up a stock of imprints

which turn out to be for all practical purposes the same as the next person's. How

must we envisage this social product, so that the language itself can be seen to be

clearly distinct from the rest? If we could collect the totality of word patterns stored in

all those individuals, we should have the social bond which constitutes their language.

It is a fund accumulated by the members of the community through the practice of

speech, a grammatical system existing potentially in every brain, or more exactly in

the brains of a group of individuals; for the language is never complete in any single

individual, but exists perfectly only in the collectivity.

By distinguishing between the language itself and speech, we distinguish at the

same time: (1) what is social from what is individual, and (2) what is essential from

what is ancillary and more or less accidental.

The language itself is not a function of the speaker. It is the product passively

registered by the individual. It never requires premeditation, and reflexion enters into

it only for the activity of classifying to be discussed below.

Speech, on the contrary, is an individual act of the will and the intelligence, in

which one must distinguish: (1) the combinations through which the speaker uses the

code provided by the language in order to express his own thought, and (2) the

psycho-physical mechanism which enables him to externalise these combinations.

It should be noted that we have defined things, not words. Consequently the

distinctions established are not affected by the fact that certain ambiguous terms have

no exact equivalents in other languages. Thus in German the word Sprache covers

individual languages as well as language in general, while Rede answers more or less

to 'speech', but also has the special sense of 'discourse'. In Latin the word sermo

covers language in general and also speech, while lingua is the word for 'a language';

and so on. No word corresponds precisely to any one of the notions we have tried to

specify above. That is why all definitions based on words are vain. It is an error of

method to proceed from words in order to give definitions of things.

To summarise, then, a language as a structured system may be characterised as

follows:

1. Amid the disparate mass of facts involved in language, it stands out as a well

defined entity. It can be localised in that particular section of the speech circuit where

sound patterns are associated with concepts. It is the social part of language, external

to the individual, who by himself is powerless either to create it or to modify it. It

exists only in virtue of a kind of contract agreed between the members of a

community. On the other hand, the individual needs an apprenticeship in order to

acquaint himself with its workings: as a child, he assimilates it only gradually. It is

quite separate from speech: a man who loses the ability to speak none the less retains

his grasp of the language system, provided he understands the vocal signs he hears.

2. A language system, as distinct from speech, is an object that may be studied

independently. Dead languages are no longer spoken, but we can perfectly well

acquaint ourselves with their linguistic structure. A science which studies linguistic

structure is not only able to dispense with other elements of language, but is possible

only if those other elements are kept separate.

3.

While language in general is heterogeneous, a language system is

homogeneous in nature. It is a system of signs in which the one essential is the union

of sense and sound pattern, both parts of the sign being psychological.

4. Linguistic structure is no less real than speech, and no less amenable to study.

Linguistic signs, although essentially psychological, are not abstractions. The

associations, ratified by collective agreement, which go to make up the language are

realities localised in the brain. Moreover, linguistic signs are, so to speak, tangible:

writing can fix them in conventional images, whereas it would be impossible to

photograph acts of speech in all their details. The utterance of a word, however small,

involves an infinite number of muscular movements extremely difficult to examine

and to represent. In linguistic structure, on the contrary, there is only the sound pattern,

and this can be represented by one constant visual image. For if one leaves out of

account that multitude of movements required to actualise it in speech, each sound

pattern, as we shall see, is only the sum of a limited number of elements or speech

sounds, and these can in turn be represented by a corresponding number of symbols in

writing. Our ability to identify elements of linguistic structure in this way is what

makes it possible for dictionaries and grammars to give us a faithful representation of

a language. A language is a repository of sound patterns, and writing is their tangible

form.

(from Chapter III The Object of Study in Saussure, F. de (1983). Course in General

Linguistics. Gerald Duckworth& Co. Ltd)

Text 2

Language as Social Semiotic

1 Introductory

Sociolinguistics sometimes appears to be a search for answers which have no questions. Let

us therefore enumerate at this point some of the questions that do seem to need answering.

1 How do people decode the highly condensed utterances of everyday speech, and how

do they use the social system for doing so?

2 How do people reveal the ideational and interpersonal environment within which what

they are saying is to be interpreted? In other words, how do they construct the social contexts

in which meaning takes place?

3 How do people relate the social context to the linguistic system? In other words, how

do they deploy their meaning potential in actual semantic exchanges?

4 How and why do people of different social class or other subcultural groups develop

different dialectal varieties and different orientations towards meaning?

5 How far are children of different social groups exposed to different verbal patterns of

primary socialization, and how does this determine their reactions to secondary socialization

especially in school?

6 How and why do children learn the functional-semantic system of the adult language?

7 How do children, through the ordinary everyday linguistic interaction of family and

peer group, come to learn the basic patterns of the culture: the social structure, the systems of

knowledge and of values, and the diverse elements of the social semiotic?

2 Elements of a sociosemiotic theory of language

There are certain general concepts which seem to be essential ingredients in a sociosemiotic

theory of language. These are the text, the situation, the text variety or register, the code (in

Bernstein's sense), the linguistic system (including the semantic system), and the social

structure.

2.1

Text

Let us begin with the concept of text, the instances of linguistic interaction in which people

actually engage: whatever is said, or written, in an operational context, as distinct from a

citational context like that of words listed in a dictionary.

For some purposes it may suffice to conceive of a text as a kind of ‘supersentence’, a

linguistic unit that is in principle greater in size than a sentence but of the same kind. It has

long been clear, however, that discourse has its own structure that is not constituted out of

sentences in combination; and in a sociolinguistic perspective it is more useful to think of

text as encoded in sentences, not as composed of them, (Hence what Cicourel (1969) refers

to as omissions by the speaker are not so much omissions as encodings, which the hearer can

decode because he shares the principles of realization that provide the key to the code.) In

other words, a text is a semantic unit; it is the basic unit of the semantic process.

At the same time, text represents choice. A text is ‘what is meant’, selected from the total

set of options that constitute what can be meant. In other words, text can be defined as

actualized meaning potential.

The meaning potential, which is the paradigmatic range of semantic choice that is present

in the system, and to which the members of a culture have access in their language, can be

characterized in two ways, corresponding to Malinowski’s distinction between the ‘context of

situation’ and the ‘context of culture’(1923, 1935). Interpreted in the context of culture, it is

the entire semantic system of the language. This is a fiction, something we cannot hope to

describe. Interpreted in the context of situation, it is the particular semantic system, or set of

subsystems, which is associated with a particular type of situation or social context. This too

is a fiction; but it is something that may be more easily describable (cf. 2.5 below). In

sociolinguistic terms the meaning potential can be represented as the range of options that is

characteristic of a specific situation type.

2.2 Situation

The situation is the environment in which the text comes to life. This is a well-established

concept in linguistics, going back at least to Wegener (1885). It played a key part in

Malinowski’s ethnography of language, under the name of ‘context of situation ’;

Malinowski’s notions were further developed and made explicit by Firth (1957, 182), who

maintained that the context of situation was not to be interpreted in concrete terms as a sort

of audiovisual record of the surrounding ‘props’ but was, rather, an abstract representation of

the environment in terms of certain general categories having relevance to the text. The

context of situation may be totally remote from what is going on roundabout during the act

of speaking or of writing.

It will be necessary to represent the situation in still more abstract terms if it is to have a

place in a general sociolinguistic theory; and to conceive of it not as situation but as situation

type, in the sense of what Bernstein refers to as a ‘social context’. This is, essentially, a

semiotic structure. It is a constellation of meanings deriving from the semiotic system that

constitutes the culture.

If it is true that a hearer, given the right information, can make sensible guesses about what

the speaker is going to mean—and this seems a necessary assumption, seeing that

communication does take place — then this ‘right information’ is what we mean by the social

context. It consists of those general properties of the situation which collectively function as

the determinants of text, in that they specify the semantic configurations that the speaker will

typically fashion in contexts of the given type.

However, such information relates not only ‘downward’ to the text but also ‘upward’, to

the linguistic system and to the social system. The ‘situation’ is a theoretical socio linguistic

construct; it is for this reason that we interpret a particular situation type, or social context, as

a semiotic structure. The semiotic structure of a situation type can be represented as a

complex of three dimensions: the ongoing social activity, the role relationships involved, and

the symbolic or rhetorical channel. We refer to these respectively as ‘field’, ‘tenor’ and

‘mode’ (following Halliday et al. 1964, as modified by Spencer and Gregory 1964; and cf.

Gregory 1967). The field is the social action in which the text is embedded; it includes the

subject-matter, as one special manifestation. The tenor is the set of role relationships among

the relevant participants; it includes levels of formality as one particular instance. The mode

is the channel or wavelength selected, which is essentially the function that is assigned to

language in the total structure of the situation; it includes the medium (spoken or written),

which is explained as a functional variable.

Field, tenor and mode are not kinds of language use, nor are they simply components of

the speech setting. They are a conceptual framework for representing the social context as

the semiotic environment in which people exchange meanings. Given an adequate

specification of the semiotic properties of the context in terms of field, tenor and mode we

should be able to make sensible predictions about the semantic properties of texts associated

with it. To do this, however, requires an intermediary level-some concept of text variety, or

register

2.3 Register

The term ‘register’ was first used in this sense, that of text variety, by Reid (1956); the

concept was taken up and developed by Jean Ure (Ure and Ellis 1972), and interpreted

within Hill's (1958) ‘institutional linguistic’ framework by Halliday et al. (1964). The

register is the semantic variety of which a text may be regarded as an instance.

Like other related concepts, such as ‘speech variant’ and ‘(sociolinguistic) code’ (Ferguson

1971, chs. 1 and 2; Gumperz 1971, part I), register was originally conceived of in

lexicogrammatical terms. Halliday et al. (1964) drew a primary distinction between two

types of language variety: dialect, which they defined as variety according to the user, and

register, which they defined as variety according to the use. The dialect is what a person

speaks, determined by who he is; the register is what a person is speaking, deter-mined by

what he is doing at the time. This general distinction can be accepted, but, instead of

characterizing a register largely by its lexicogrammatical properties, we shall suggest, as

with text, a more abstract definition in semantic terms.

A register can be defined as the configuration of semantic resources that the member of a

culture typically associates with a situation type. It is the meaning potential that is accessible

in a given social context. Both the situation and the register associated with it can be

described to varying degrees of specificity; but the existence of registers is a fact of everyday

experience—speakers have no difficulty in recognizing the semantic options and

combinations of options that are ‘at risk’ under particular environmental conditions. Since

these options are realized in the form of grammar and vocabulary, the register is recognizable

as a particular selection of words and structures. But it is defined in terms of meanings; it is

not an aggregate of conventional forms of expression superposed on some underlying

content by ‘social factors’ of one kind or another. It is the selection of meanings that

constitutes the variety to which a text belongs.

2.4 Code

‘Code’ is used here in Bernstein’s sense; it is the principle of semiotic organization

governing the choice of meanings by a speaker and their interpretation by a hearer. The code

controls the semantic styles of the culture.

Codes are not varieties of language, as dialects and registers are. The codes are, so to

speak, ‘above’ the linguistic system; they are types of social semiotic, or symbolic orders of

meaning generated by the social system (cf. Hasan 1973). The code is actualized in language

through the register, since it determines the semantic orientation of speakers in particular

social contexts; Bernstein's own use of ‘variant’ (as in ‘elaborated variant’) refers to those

characteristics of a register which derive from the form of the code. When the semantic

systems of the language are activated by the situational determinants of text—the field, tenor

and mode—this process is regulated by the codes.

Hence the codes transmit, or control the transmission of, the underlying patterns of a

culture or subculture, acting through the socializing agencies of family, peer group and

school. As a child comes to attend to and interpret meanings, in the context of situation and

in the context of culture, at the same time he takes over the code. The culture is transmitted

to him with the code acting as a filter, defining and making accessible the semiotic principles

of his own subculture, so that as he learns the culture he also learns the grid, or subcultural

angle on the social system. The child’s linguistic experience reveals the culture to him

through the code, and so transmits the code as part of the culture.

2.5

The linguistic system

Within the linguistic system, it is the semantic system that is of primary concern in a socio

linguistic context. Let us assume a model of language with a semantic, a lexicogrammatical

and a phonological stratum; this is the basic pattern underlying the (often superficially more

complex) interpretations of language in the work of Trubetzkoy, Hjelmslev, Firth, Jakobson,

Martinet, Pottier, Pike, Lamb, Lakoff and McCawley (among many others). We can then

adopt the general conception of the organization of each stratum, and of the realization

between strata, that is embodied in Lamb's stratification theory (Lamb 1971; 1974).

The semantic system is Lamb’s ‘semological stratum’; it is conceived of here, however, in

functional rather than in cognitive terms. The conceptual framework was already referred to

in chapter 3, with the terms ‘ideational’, ‘interpersonal’, and ‘textual’. These are to be

interpreted not as functions in the sense of ‘uses of language’, but as functional components

of the semantic system — ‘metafunctions’ as we have called them. (Since in respect both of

the stratal and of the functional organization of the linguistic system we are adopting a ternary

interpretation rather than a binary one, we should perhaps explicitly disavow any particular

adherence to the magic number three. In fact the functional interpretation could just as readily

be stated in terms of four components, since the ideational comprises two distinct subparts, the

experiential and the logical; see Halliday 1973; 1976; also chapter 7 below.)

What are these functional components of the semantic system? They are the modes of

meaning that are present in every use of language in every social context. A text is a product

of all three; it is a polyphonic composition in which different semantic melodies are

interwoven, to be realized as integrated lexicogramrnatical structures. Each functional

component contributes a band of structure to the whole.

The ideational function represents the speaker’s meaning potential as an observer. It is the

content function of language, language as ‘about some-thing’. This is the component through

which the language encodes the cultural experience, and the speaker encodes his own

individual experience as a member of the culture. It expresses the phenomena of the

environment: the things—creatures, objects, actions, events, qualities, states and relations

—of the world and of our own consciousness, including the phenomenon of language itself;

and also the ‘metaphenomena’, the things that are already encoded as facts and as reports. All

these are part of the ideational meaning of language.

The interpersonal component represents the speaker’s meaning potential as an intruder. It

is the participatory function of language, language as doing something. This is the

component through which the speaker intrudes himself into the context of situation, both

expressing his own attitudes and judgements and seeking to influence the attitudes and

behaviour of others. It expresses the role relationships associated with the situation,

including those that are defined by language itself, relationships of questioner-respondent,

informer-doubter and the like. These constitute the interpersonal meaning of language.

The textual component represents the speaker’s text-forming potential; it is that which makes

language relevant. This is the component which provides the texture; that which makes the

difference between language that is suspended in vacuo and language that is operational in a

context of situation. It expresses the relation of the language to its environment, including

both the verbal environment—what has been said or written before —and the nonverbal,

situational environment. Hence the textual component has an enabling function with respect

to the other two; it is only in combination with textual meanings that ideational and

interpersonal meanings are actualized.

These components are reflected in the lexicogramrnatical system in the form of discrete

networks of options. In the clause, for example, the ideational function is represented by

transitivity, the interpersonal by mood and modality, and the textual by a set of systems that

have been referred to collectively as ‘theme’. Each of these three sets of options is

characterized by strong internal but weak external constraints: for example, any choice made

in transitivity has a significant effect on other choices within the transitivity systems, but has

very little effect on choices within the mood or theme systems. Hence the functional

organization of meaning in language is built in to the core of the linguistic system, as the

most general organizing principle of the lexicogrammatical stratum.

2.6 Social structure

Of the numerous ways in which the social structure is implicated in a sociolinguistic theory,

there are three which stand out. In the first place, it defines and gives significance to the

various types of social context in which meanings are exchanged. The different social groups

and communication networks that determine what we have called the ‘tenor’ —the status and

role relationships in the situation —are obviously products of the social structure; but so also

in a more general sense are the types of social activity that constitute the ‘field’. Even the

‘mode’, the rhetorical channel with its associated strategies, though more immediately

reflected in linguistic patterns, has its origin in the social structure; it is the social structure that

generates the semiotic tensions and the rhetorical styles and genres that express them (Barthes

1970).

Secondly, through its embodiment in the types of role relationship within the family, the

social structure determines the various familial patterns of communication; it regulates the

meanings and meaning styles that are associated with given social contexts, including those

contexts that are critical in the processes of cultural transmission. In this way, the social

structure determines, through the intermediary of language, the forms taken by the

socialization of the child (See Bernstein 1971; 1975.)

Thirdly, and most problematically, the social structure enters in through the effects of social

hierarchy, in the form of caste or class. This is obviously the background to social dialects,

which are both a direct manifestation of social hierarchy and also a symbolic expression of it,

maintaining and reinforcing it in a variety of ways: for example, the association of dialect

with register —the fact that certain registers conventionally call for certain dialectal modes

—expresses the relation between social classes and the division of labour. In a more pervasive

fashion, the social structure is present in the forms of semiotic interaction, and becomes

apparent through incongruities and disturbances in the semantic system. Linguistics seems

now to have largely abandoned its fear of impurity and come to grips with what is called

‘fuzziness’ in language; but this has been a logical rather than a sociological concept, a

departure from an ideal regularity rather than an organic property of sociosemiotic systems.

The ‘fuzziness’ of language is in part an expression of the dynamics and the tensions of the

social system. It is not only the text (what people mean) but also the semantic system (what

they can mean) that embodies the ambiguity, antagonism, imperfection, inequality and

change that characterize the social system and social structure. This is not often

systematically explored in linguistics, though it is familiar enough to students of

communication and of general semantics, and to the public at large. It could probably be

fruitfully approached through an extension of Bernstein's theory of codes (cf. Douglas 1972).

The social structure is not just an ornamental background to linguistic interaction, as it has

tended to become in sociolinguistic discussions. It is an essential element in the evolution of

semantic systems and semantic processes.

(from Chapter II 6 Language as Social Semiotic in Halliday, M.A.K (1978). Language as

Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. Edward Arnold.)

Text 3

Knowledge of Language as a Focus of Inquiry

The study of language has a long and rich history, extending over thousands of years. This

study has frequently been understood as an inquiry into the nature of mind and thought on the

assumption that "languages are the best mirror of the human mind" (Leibniz). A common

conception was that "with respect to its substance grammar is one and the same in all

languages, though it does vary accidentally" (Roger Bacon). The invariant "substance" was

often taken to be the mind and its acts; particular languages use various mechanisms—some

rooted in human reason, others arbitrary and adventitious—for the expression of thought,

which is a constant across languages. One leading eighteenth century rational grammarian

defined "general grammar" as a deductive science concerned with "the immutable and general

principles of spoken or written language" and their consequences; it is "prior to all languages,"

because its principles "are the same as those that direct human reason in its intellectual

operations" (Beauzee). Thus, "the science of language does not differ at all from the science of

thought." "Particular grammar" is not a true "science" in the sense of this rationalist tradition

because it is not based solely on universal necessary laws; it is an "art" or technique that shows

how given languages realize the general principles of human reason. As John Stuart Mill later

expressed the same leading idea, "The principles and rules of grammar are the means by which

the forms of language are made to correspond with the universal forms of thought….The

structure of every sentence is a lesson in logic." Others, particularly during the Romantic

period, argued that the nature and content of thought are determined in part by the devices

made available for its expression in particular languages. These devices may include

contributions of individual genius that affect the "character" of a language, enriching its

means of expression and the thoughts expressed without affecting its "form," its sound

system and rules of word and sentence formation (Humboldt).

With regard to the acquisition of knowledge, it was widely held that the mind is not "so

much to be filled therewith from without, like a vessel, as to be kindled and awaked" (Ralph

Cudworth); "The growth of knowledge... [rather resembles]... the growth of Fruit; however

external causes may in some degree cooperate, it is the internal vigour, and virtue of the tree,

that must ripen the juices to their just maturity" (James Harris). Applied to language, this

essentially Platonistic conception would suggest that knowledge of a particular language

grows and matures along a course that is in part intrinsically determined, with modifications

reflecting observed usage, rather in the manner of the visual system or other bodily "organs"

that develop along a course determined by genetic instructions under the triggering and

shaping effects of environmental factors.

With the exception of the relativism of the Romantics, such ideas were generally regarded

with much disapproval in the mainstream of linguistic research by the late nineteenth century

and on through the 1950s. In part, this attitude developed under the impact of a rather

narrowly construed empiricism and later behaviorist and operationalist doctrine. In part, it

resulted from the quite real and impressive successes of historical and descriptive studies

conducted within a narrower compass, specifically, the discovery of "sound laws" that

provided much understanding of the history of languages and their relationships. In part, it

was a natural consequence of the investigation of a much richer variety of languages than

were known to earlier scholars, languages that appeared to violate many of the allegedly a

priori conceptions of the earlier rationalist tradition. After a century of general neglect or

obloquy, ideas resembling those of the earlier tradition re-emerged (initially, with virtually

no awareness of historical antecedents) in the mid-1950s, with the development of what came

to be called "generative grammar"—again, reviving a long-lapsed and largely forgotten

tradition.

The generative grammar of a particular language (where "generative" means nothing more

than "explicit") is a theory that is concerned with the form and meaning of expressions of this

language. One can imagine many different kinds of approach to such questions, many points

of view that might be adopted in dealing with them. Generative grammar limits itself to

certain elements of this larger picture. Its standpoint is that of individual psychology. It is

concerned with those aspects of form and meaning that are determined by the "language

faculty", which is understood to be a particular component of the human mind. The nature of

this faculty is the subject matter of a general theory of linguistic structure that aims to

discover the framework of principles and elements common to attainable human languages;

this theory is now often called "universal grammar" (UG), adapting a traditional term to a

new context of inquiry. UG may be regarded as a characterization of the genetically

determined language faculty. One may think of this faculty as a "language acquisition

device," an innate component of the human mind that yields a particular language through

interaction with presented experience, a device that converts experience into a system of

knowledge attained: knowledge of one or another language.

The study of generative grammar represented a significant shift of focus in the approach to

problems of language. Put in the simplest terms, to be elaborated below, the shift of focus

was from behavior or the products of behavior to states of the mind/brain that enter into

behavior. If one chooses to focus attention on this latter topic, the central concern becomes

knowledge of language: its nature, origins, and use.

The three basic questions that arise, then, are these:

(i)

What constitutes knowledge of language?

(1)

(ii)

How is knowledge of language acquired?

(iii)

How is knowledge of language put to use?

The answer to the first question is given by a particular generative grammar, a theory

concerned with the state of the mind/brain of the person who knows a particular language.

The answer to the second is given by a specification of UG along with an account of the

ways in which its principles interact with experience to yield a particular language; UG is a

theory of the "initial state" of the language faculty, prior to any linguistic experience. The

answer to the third question would be a theory of how the knowledge of language attained

enters into the expression of thought and the understanding of presented specimens of

language, and derivatively, into communication and other special uses of language.

So far, this is nothing more than the outline of a research program that takes up classical

questions that had been put aside for many years. As just described, it should not be particularly controversial, since it merely expresses an interest in certain problems and offers a

preliminary analysis of how they might be confronted, although as is often the case, the

initial formulation of a problem may prove to be far-reaching in its implications, and

ultimately controversial as it is developed.

Some elements of this picture may appear to be more controversial than they really are.

Consider, for example, the idea that there is a language faculty, a component of the mind/

brain that yields knowledge of language given presented experience. It is not at issue that

humans attain knowledge of English, Japanese, and so forth, while rocks, birds, or apes do

not under the same (or indeed any) conditions. There is, then, some property of the

mind/brain that differentiates humans from rocks, birds, or apes. Is this a distinct "language

faculty" with specific structure and properties, or, as some believe, is it the case that humans

acquire language merely by applying generalized learning mechanisms of some sort, perhaps

with greater efficiency or scope than other organisms? These are not topics for speculation or

a priori reasoning but for empirical inquiry, and it is clear enough how to proceed: namely,

by facing the questions of (1). We try to determine what is the system of knowledge that has

been attained and what properties must be attributed to the initial state of the mind/brain to

account for its attainment. Insofar as these properties are language-specific, either

individually or in the way they are organized and composed, there is a distinct language

faculty.

Generative grammar is sometimes referred to as a theory, advocated by this or that person.

In fact, it is not a theory any more than chemistry is a theory. Generative grammar is a topic,

which one may or may not choose to study. Of course, one can adopt a point of view from

which chemistry disappears as a discipline (perhaps it is all done by angels with mirrors). In

this sense, a decision to study chemistry does stake out a position on matters of fact.

Similarly, one may argue that the topic of generative grammar does not exist, although it is

hard to see how to make this position minimally plausible. Within the study of generative

grammar there have been many changes and differences of opinion, often reversion to ideas

that had been abandoned and were later reconstructed in a different light. Evidently, this is a

healthy phenomenon indicating that the discipline is alive, although it is sometimes, oddly,

regarded as a serious deficiency, a sign that something is wrong with the basic approach. I

will review some of these changes as we proceed.

In the mid-1950s, certain proposals were advanced as to the form that answers to the

questions of (1) might take, and a research program was inaugurated to investigate the

adequacy of these proposals and to sharpen and apply them. This program was one of the

strands that led to the development of the cognitive sciences in the contemporary sense,

sharing with other approaches the belief that certain aspects of the mind/brain can be usefully

construed on the model of computational systems of rules that form and modify

representations, and that are put to use in interpretation and action. From its origins (or with a

longer perspective, one might say "its reincarnation") about 30 years ago, the study of

generative grammar was undertaken with an eye to gaining some insight into the nature and

origins of systems of knowledge, belief, and understanding more broadly, in the hope that

these general questions could be illuminated by a detailed investigation of the special case of

human language.

……

Traditional and structuralist grammar did not deal with the questions of (1), the former

because of its implicit reliance on the unanalyzed intelligence of the reader, the latter because

of its narrowness of scope. The concerns of traditional and generative grammar are, in a

certain sense, complementary: a good traditional or pedagogical grammar provides a full list

of exceptions (irregular verbs, etc.), paradigms and examples of regular constructions, and

observations at various levels of detail and generality about the form and meaning of

expressions. But it does not examine the question of how the reader of the grammar uses

such information to attain the knowledge that is used to form and interpret new expressions,

or the question of the nature and elements of this knowledge: essentially the questions of (1),

above. Without too much exaggeration, one could describe such a grammar as a structured

and organized version of the data presented to a child learning a language, with some general

commentary and often insightful observations. Generative grammar, in contrast, is concerned

primarily with the intelligence of the reader, the principles and procedures brought to bear to

attain full knowledge of a language. Structuralist theories, both in the European and

American traditions, did concern themselves with analytic procedures for deriving aspects of

grammar from data, as in the procedural theories of Nikolay Trubetzkoy, Zellig Harris,

Bernard Bloch, and others, but primarily in the areas of phonology and morphology. The

procedures suggested were seriously inadequate and in any event could not possibly be

understood (and were not intended) to provide an answer to question (1ii), even in the

narrower domains where most work was concentrated. Nor was there an effort to determine

what was involved in offering a comprehensive account of the knowledge of the

speaker/hearer.

As soon as these questions were squarely faced, a wide range of new phenomena were

discovered, including quite simple ones that had passed unnoticed, and severe problems arose

that had previously been ignored or seriously misunderstood. A standard belief 30 years ago

was that language acquisition is a case of "overlearning". Language was regarded as a habit

system, one that was assumed to be much overdetermined by available evidence. Production

and interpretation of new forms was taken to be a straightforward matter of analogy, posing

no problems of principle. Attention to the questions of (1) quickly reveals that exactly the

opposite is the case: language poses in a sharp and clear form what has sometimes been

called "Plato's problem," the problem of "poverty of stimulus," of accounting for the richness,

complexity, and specificity of shared knowledge, given the limitations of the data available.

This difference of perception concerning where the problem lies— overlearning or poverty of

evidence—reflects very clearly the effect of the shift of focus that inaugurated the study of

generative grammar.

(from Chapter 1 Knowledge of Language as a Focus of Inquiry in Noam Chomsky(1985),

Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin, and Use. Greenwood Publishing Group.)

Text 4

The Domain of Linguistics: An Overview

Geoff Nunberg and Tom Wasow

An Example of Language Use

Pat: Why did the chicken cross the road?

Chris: I give up.

Pat: To get to the other side.

Most of us heard this joke when we were small children and find nothing remarkable in the

ability to engage in such exchanges. But a bit of reflection reveals that even such a mundane

use of language involves an amazing combination of abilities.

Think about it: Pat makes some vocal noises, with the effect that Chris entertains thoughts of

a scenario involving a fowl and a thoroughfare. This leads to an exchange of utterances,

possibly laughter, and the conviction by both parties that Pat has 'told a joke'.

Prerequisites for Language Use

What does it take to make communication through language succeed? Here are just a few of

the many things that are necessary for the exchange above:

Pat's first two words 'why did' sound exactly the same as 'wide id'. Breaking the stream of

sounds into words requires that Chris pays attention to the wider context and knows what

makes sense and what doesn't.

Words like 'chicken' and 'cross' have lots of meanings (consider, for example, one gangster

saying to another, 'You won't cross me because you're chicken'). To conjure up the image of

a bird and a highway, Chris must identify the right choices for these.

Pat has to know to say 'cross', not 'crossed' or 'crossing' in this context.

The order of words could not be 'Why the chicken did cross the road?' or any of lots of other

conceivable orders.

Chris's utterance ('I give up') is entirely conventional, signalling recognition that Pat is posing

a riddle, and that Chris is ready to hear the punchline. The recognition that the first sentence

was a riddle again depends on its relation to the wider context and cultural knowledge.

The punchline is not a complete sentence; Chris must recognize that it means that the chicken

crossed the road in order to get to the other side.

In order to get the joke, Chris must know that answers to such 'why' questions normally

involve some longer-term objective.

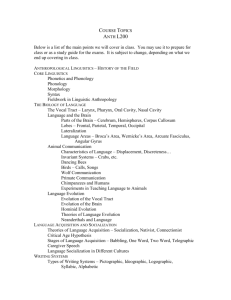

The Domain of Linguistics

Linguistics, the study of language, concerns itself with all aspects of how people use

language and what they must know in order to do so. As a universal characteristic of the

species, language has always held a special fascination for human beings, and the history of

linguistics as a systematic field of study goes back almost three thousand years.

Modern linguists concern themselves with many different facets of language, from the

physical properties of the sound waves in utterances to the intentions of speakers towards

others in conversations and the social contexts in which conversations are embedded. The

branches of linguistics are concerned with how languages are structured, how languages are

used, and how they change.

Language as a Formal System

Linguistic structure can be studied at many different levels. The sounds of language can be

investigated by looking at the physics of the speech stream and by studying the physiology of

the vocal tract and auditory system. A more psychological approach is also possible, namely

considering what physical properties of the vocal tract or muscalature are used to make

linguistic distinctions, and how the sounds of languages pattern.

Words, phrases, and sentences have internal structure. Many words are made up of smaller

meaningful units, such as stems and suffixes; for example, stem 'happy' + suffix '-ly'.

Linguists investigate the different ways such pieces can be put together to form words, a

study called morphology. Likewise, words cluster together into phrases, which combine to

make sentences, and linguists explore the rules governing such combinations. The scientific

study of word structure and sentence structure is what modern linguists mean by the term

grammar; this is quite different from the sort of 'normative' grammar instruction aimed to

teach 'proper usage' common in primary and secondary school, which linguists call

prescriptivism. Words and sentences are used to convey meanings.

Linguists study this too, seeking to specify precisely what words mean, how they combine

into sentence meanings, and how these combine with contextual information to convey the

speaker's thoughts. The first two of these areas of investigation are called semantics, and the

third is called pragmatics.

Language as a Human Phenomenon

Even the most formal and abstract work on linguistic structure is colored by the awareness

that language is a uniquely human phenomenon. It is lodged in human brains; it is passed on

from one generation to the next; it is intimately bound up with the forms of human thought.

Unlike a specialized system like arithmetic, it serves a vast range of communicative

needs—from getting your neighbor to keep the weeds down, to reporting simple facts, telling

jokes, making declarations of love, or praying to a deity. And of course it functions in the

midst of complex societies, not just as a means of communication, but as a marker of social

identity—a sign of membership in a social class, ethnic group, or nation. It isn't surprising,

then, that linguistic research shares some concerns with just about every one of the human

sciences, from psychology and neurology to literary study, anthropology, sociology, and

political science.

All languages change. In other words, languages have histories, and a complete

understanding of a linguistic structure often involves examining variation and change in the

language under investigation. This is extremely difficult in most cases, because the vast

majority of languages have had no writing systems until very recently.

Important as historical explanations and evidence are in linguistics, they are not necessary for

competent language use—and most speakers don't know anything about them. Hence, most

linguistic explanations focus on what speakers must know in order to speak and understand

language the way all normal humans do. There are many facets to the study of language and

brain. It encompasses both child language acquisition and how adults produce and process

language.

One particularly fascinating question is whether our language shapes the way we perceive the

world and if so, how? In particular, can there be thinking without language? Such questions

have fascinated people for thousands of years, but only in recent times have researchers been

in a position to examine them scientifically and to investigate how languages can reflect or

reinforce particular ways of looking at the world and the world-views of particular cultures.

Linguists document the remarkable diversity of means of expression employed in the

languages of the world. At the same time, though, researchers have come to understand that

many of the features of language are universal, both because there are universal aspects to

human experience and because language has a built-in biological basis. This latter subject

belongs to the subfield called neurolinguistics, which studies how language is realized in the

human brain. The connection can be revealed through experiment or by studying the way

brain damage can lead to disruptions of language function in disorders like dyslexia or

aphasia. Or it can be revealed in more subtle ways, like the slips of the tongue that people

make, which can shed light on the mental circuitry of language in something like the way a

computer malfunction can shed light on how it is programmed or how its hardware was

designed. It can also be revealed by the changes that can take place in language and by the

limitations which make some changes impossible.

Language as a Social Phenomenon

The social life of language begins with the smallest and most informal interactions. Every

conversation is a social transaction, governed by rules that determine how sentences are put

together into larger discourses—stories, jokes, or whatever—and how participants take turns

speaking and let each other know that they are attending to what is being said. The

organization of these interactions is the subject of the subfield called discourse analysis.

Another, related, area of study concerns the literary uses of language, which involve the

particular rules that shape poetic structure or the organization of forms like the sonnet or the

novel, and which often make special use of devices like metaphor—though to be sure,

linguists have discovered too that metaphor and figurative language are essential elements of

everyday forms of speech.

At a larger level, the field of sociolinguistics is also concerned with the way the divisions of

societies into social classes and ethnic, religious, and racial groups are often mirrored by

linguistic differences. Of particular interest here, too, is the way language is used differently

by men and women.

In most parts of the world, communities use more than one language, and the phenomenon of

bilingualism or multilingualism has a special interest for linguists. Multilingualism raises

particular psychological questions: How do two or more languages coexist within an

individual mind? How do bilingual individuals decide when to switch from one language to

another? It also raises questions at the level of the community, where the question of which

language to use is determined by tacit understandings, and sometimes by official rules and

regulations that may invoke difficult questions about the relation of language to nationality.

In many nations, including the US, there are currently important debates about establishing

an official language.

Multilingual communities are interesting to linguists for another reason: Languages that

come into contact can influence each other in various ways, sometimes converging in

grammar or other features. Under certain social conditions, a mix of languages can give rise

to 'new' languages called pidgins and creoles, which have a particular interest for linguists

because of the way they shed light on language structure and function. Often, though, the

result when languages come into contact is that one becomes dominant at the expense of the

other, especially when the contact pits a widely used language of a powerful community

against a local or minority language. Modern communications have accelerated this process,

to the point where the majority of the languages currently used in the world are endangered,

and may disappear within a few generations—a situation that causes linguists concerns that

go beyond the purely academic.

Applications of Linguistics

Linguistics can have applications wherever language itself becomes a matter of practical

concern. Strictly speaking, then, the domain of applied linguistics is not a single field or

subfield, but can range from the research on multilingualism the teaching and learning of

foreign languages to studies of neurolinguistic disorders like aphasia and of various speech

and hearing defects. It includes work in the area of language planning, like the efforts to

devise writing systems for languages in the post-colonial world, and the efforts to standardize

terminologies for various technical domains, or to revitalize endangered languages.

Examples of the applications of linguistics can be multiplied indefinitely. The techniques of

discourse analysis have been applied to the problem of avoiding air accidents due to

miscommunication and to the problems of communication between members of different

ethnic groups. And linguists are increasingly called on in legal proceedings that turn on

questions of precise interpretation, a development that has given rise to a new field of study

of language and law.

Probably the oldest forms of applied linguistics are the preparation of dictionaries and the

field of interpretation and translation, all of which have been greatly influenced by the advent

of the computer. The applications of computers to language have not been limited to these

areas, though; they extend to the development of interfaces that enable people to interact with

computers using ordinary language, of systems capable of understanding speech and writing,

and of techniques that allow people to retrieve information more effectively from text

databases or from the Web. Not surprisingly, then, an increasing number of linguists are

working in high-tech industries.

(from http://www.lsadc.org/info/ling-fields-overview.cfm)

Text 5

Why Major in Linguistics?

Monica Macaulay and Kristen Syrett

What is linguistics?

If you are considering a linguistics major, you probably already know at least something

about the field. However, you may find it hard to answer people who ask you, "What exactly

is linguistics, and what do linguists do?" They might assume that it means that you are

multilingual. And you may, in fact, be a polyglot, but that's not what this major is about.

Linguistics is, broadly, the scientific study of language, and many topics are studied under

this umbrella.

At the heart of linguistics is the search for the unconscious knowledge that humans have

about language(s), an understanding of the structure of language, and knowledge about how

languages differ from each other. What exactly do we mean by this? When you were born,

you were not able to communicate with the adults around you using their language. But by

the time you were five or six, you were able to produce sentences, understand jokes, make

rhymes, and so on. In short, you became a fluent native speaker. All of this happened before

you entered first grade! (If you studied a foreign language in high school, you know that

learning a language later in life did not go nearly as smoothly or as quickly.) During those

first few years of your life, you accumulated a wide range of knowledge about language.

Speakers of all languages know a lot about their languages, usually without knowing that

they know it. For example, as a speaker of American English, you possess knowledge about

word order: You understand that Sarah admires the teacher is grammatical, while Admires

Sarah teacher the is not, and also that The teacher admires Sarah means something entirely

different. You know that when you ask a yes-no question, you may reverse the order of

words at the beginning of the sentence and that your voice goes up at the end of the sentence

(for example, in Are you going?). However, if you speak French, you might add est-ce que at

the beginning; if you speak Japanese, you probably add ka at the end; and if you know

American Sign Language, you raise your eyebrows during the question. In addition, you

understand that asking a wh-question (who, what, where, etc.) calls for a somewhat different

strategy (compare the rising intonation in the question above to the falling intonation in

Where are you going?). You also possess knowledge about the sounds of your language, e.g.

which consonants can go together in a word. You know that slint could be an English word,

while sbint or srint could not be.

Linguists investigate how linguistic knowledge of this kind is acquired, how it interacts with

other mental processes, how it varies from person to person and region to region (even within

one language), and how computer programs can model this knowledge. They study how the

structure of language (such as sounds or phrases) can be represented, and how different

components of language interact with each other (such as intonation and meaning). Linguists

work with consultants who speak different languages, search corpora, and run carefully

designed experiments to answer these questions about language. (Yes, linguistics is a

science!) By now you can see that linguists may benefit by knowing multiple languages, but

you can see that this is not the full extent of what a linguist does.

What will I study as a linguistics major?

When you choose to major in linguistics, you're choosing a major that gives you insight into

one of the most intriguing aspects of human knowledge and behavior and at the same time

exposes you to related disciplines. Majoring in linguistics means that you will learn about

many aspects of human language, including the physical properties and structure of sounds

(phonetics and phonology), words (morphology), sentences (syntax), and meaning

(semantics). It can involve looking at how languages change over time (historical linguistics);

how they vary from situation to situation, group to group, and place to place (sociolinguistics

and dialectology); how people use language in context (pragmatics); or how people acquire

or learn language (language acquisition). Faculty members in linguistics programs are

experts in at least one (if not several) of these subfields. Many linguists, in fact, have

expertise in multiple subfields and enjoy collaborating with other linguists with different

backgrounds in order to further scientific knowledge. Linguistics programs may be organized

around different aspects of linguistics. For example, a program might focus on the linguistics

of a particular group of languages (like Slavic linguistics); how language is acquired and

processed (psycholinguistics); how language relates to social and cultural issues, including

language learning and teaching (applied linguistics); or the connections between linguistics

and cognitive science. All of these programs share an interest in the unconscious knowledge

that humans have about the language(s) that they know and what is possible or impossible in

language.

Although linguistics programs in the United States may vary in their approach, they tend to

have similar requirements. Most linguistics majors are either required or encouraged to have

proficiency in at least one language besides English. This knowledge helps students

understand how languages vary and how the students' native language fits into a broader

picture. Many linguistics majors spend time studying and/or traveling abroad. Students are

also encouraged to complement their linguistic studies with courses in related areas (such as

psychology, cognitive science, anthropology, or computer science) to be more well-rounded

and better informed.

What opportunities will I have with a linguistics degree?

In the course of their training, students who major in linguistics acquire valuable intellectual

skills, including analytic reasoning and argumentation, and learn how to study language

scientifically. This means making insightful observations, formulating and testing clear

hypotheses, making arguments and drawing conclusions, and communicating findings to a

wider community. Linguistics majors are therefore well equipped for a variety of jobs and

graduate-level programs.

Job Opportunities

A linguistics major provides students with valuable training for many different kinds of

opportunities following graduation. Some may require additional training or skills, but not all

do. Here are just a few:

Work in the computer industry: Linguists may work on speech recognition, search

engines, and artificial intelligence.

Teach at the university level: A graduate degree in linguistics allows you to teach in

departments such as linguistics, philosophy, psychology, speech/communication

sciences, anthropology, English, and foreign languages.

Work in education: People with a background in linguistics and education develop

curricula and materials, train teachers, and design tests and other methods of

assessment, especially for language arts and second language learning. At the

university level, many applied linguists are involved in teacher education and

educational research.

Teach English as a Second Language (ESL) in the United States or abroad: If

you want to teach ESL in the US, you will probably need additional training in

language pedagogy, such as a Masters degree in Education or TESOL. Many teaching

positions abroad require only an undergraduate degree, but at least some specialized

training in the subject will make you a much more effective teacher. Linguistics can

give you a valuable crosslanguage perspective.

Work as a translator or interpreter: Skilled translators and interpreters are needed

everywhere, from government to hospitals to courts of law. For this line of work, a

high level of proficiency in the relevant language(s) is necessary, and specialized

training may be required. Nonetheless, linguistics can help you understand the issues

that arise when a message is communicated from one language to another.

Work on language documentation or do fieldwork: A number of projects and

institutes around the world are looking for linguists to work with language consultants

to document, analyze, and preserve languages (many of which are endangered). Some

organizations engage in language-related fieldwork, including documenting

endangered languages, conducting language surveys, establishing literacy programs,

and translating documents of cultural heritage. This is a great way to interact with

speakers of diverse languages, representing communities around the world.

Teach a foreign language: Your students will benefit from your knowledge of

language structure and your ability to make certain aspects of the language especially

clear. You will need a high level of proficiency in the relevant language, and you may

need additional training to teach a foreign language.

Work in the publishing industry, as a technical writer, or a journalist: The verbal

skills that linguists develop are ideal for positions in editing, publishing, and writing.

Work for a testing agency: Linguists help prepare and evaluate standardized exams

and conduct research on assessment issues.

Work with dictionaries (lexicography): Knowledge of phonology, morphology,

historical linguistics, dialectology, and sociolinguistics is key to becoming a

lexicographer.

Become a consultant on language in professions such as law or medicine: The

subfield of forensic linguistics involves studying the language of legal texts, linguistic

aspects of evidence, issues of voice identification, and so on. Law enforcement

agencies such as the FBI and police departments, law firms, and the courts hire

linguists for these purposes.

Work for a product-naming company: Companies that name products do extensive

linguistic research on the associations that people make with particular sounds and

classes of sounds. A background in linguistics qualifies you for this line of work.

Work for the government: The federal government hires linguists for the Foreign

Service, the FBI, etc.

Become an actor or train actors: Actors need training in pronunciation, intonation,

and different elements of grammar in order to sound like real speakers of a language

or dialect. They may even need to know how to make mistakes to sound like an

authentic nonnative speaker.