Prose Passage Practice Test: Family, Wealth, and Religion

advertisement

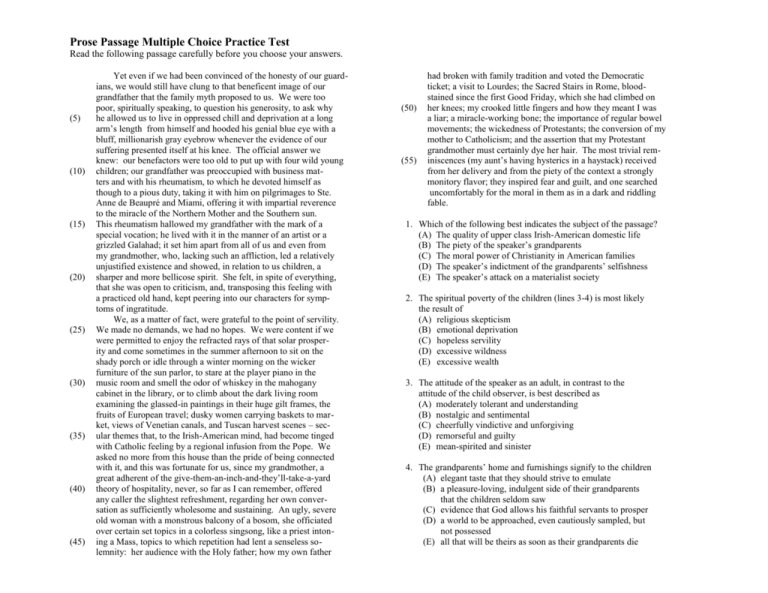

Prose Passage Multiple Choice Practice Test Read the following passage carefully before you choose your answers. (5) (10) (15) (20) (25) (30) (35) (40) (45) Yet even if we had been convinced of the honesty of our guardians, we would still have clung to that beneficent image of our grandfather that the family myth proposed to us. We were too poor, spiritually speaking, to question his generosity, to ask why he allowed us to live in oppressed chill and deprivation at a long arm’s length from himself and hooded his genial blue eye with a bluff, millionarish gray eyebrow whenever the evidence of our suffering presented itself at his knee. The official answer we knew: our benefactors were too old to put up with four wild young children; our grandfather was preoccupied with business matters and with his rheumatism, to which he devoted himself as though to a pious duty, taking it with him on pilgrimages to Ste. Anne de Beaupré and Miami, offering it with impartial reverence to the miracle of the Northern Mother and the Southern sun. This rheumatism hallowed my grandfather with the mark of a special vocation; he lived with it in the manner of an artist or a grizzled Galahad; it set him apart from all of us and even from my grandmother, who, lacking such an affliction, led a relatively unjustified existence and showed, in relation to us children, a sharper and more bellicose spirit. She felt, in spite of everything, that she was open to criticism, and, transposing this feeling with a practiced old hand, kept peering into our characters for symptoms of ingratitude. We, as a matter of fact, were grateful to the point of servility. We made no demands, we had no hopes. We were content if we were permitted to enjoy the refracted rays of that solar prosperity and come sometimes in the summer afternoon to sit on the shady porch or idle through a winter morning on the wicker furniture of the sun parlor, to stare at the player piano in the music room and smell the odor of whiskey in the mahogany cabinet in the library, or to climb about the dark living room examining the glassed-in paintings in their huge gilt frames, the fruits of European travel; dusky women carrying baskets to market, views of Venetian canals, and Tuscan harvest scenes – secular themes that, to the Irish-American mind, had become tinged with Catholic feeling by a regional infusion from the Pope. We asked no more from this house than the pride of being connected with it, and this was fortunate for us, since my grandmother, a great adherent of the give-them-an-inch-and-they’ll-take-a-yard theory of hospitality, never, so far as I can remember, offered any caller the slightest refreshment, regarding her own conversation as sufficiently wholesome and sustaining. An ugly, severe old woman with a monstrous balcony of a bosom, she officiated over certain set topics in a colorless singsong, like a priest intoning a Mass, topics to which repetition had lent a senseless solemnity: her audience with the Holy father; how my own father (50) (55) had broken with family tradition and voted the Democratic ticket; a visit to Lourdes; the Sacred Stairs in Rome, bloodstained since the first Good Friday, which she had climbed on her knees; my crooked little fingers and how they meant I was a liar; a miracle-working bone; the importance of regular bowel movements; the wickedness of Protestants; the conversion of my mother to Catholicism; and the assertion that my Protestant grandmother must certainly dye her hair. The most trivial reminiscences (my aunt’s having hysterics in a haystack) received from her delivery and from the piety of the context a strongly monitory flavor; they inspired fear and guilt, and one searched uncomfortably for the moral in them as in a dark and riddling fable. 1. Which of the following best indicates the subject of the passage? (A) The quality of upper class Irish-American domestic life (B) The piety of the speaker’s grandparents (C) The moral power of Christianity in American families (D) The speaker’s indictment of the grandparents’ selfishness (E) The speaker’s attack on a materialist society 2. The spiritual poverty of the children (lines 3-4) is most likely the result of (A) religious skepticism (B) emotional deprivation (C) hopeless servility (D) excessive wildness (E) excessive wealth 3. The attitude of the speaker as an adult, in contrast to the attitude of the child observer, is best described as (A) moderately tolerant and understanding (B) nostalgic and sentimental (C) cheerfully vindictive and unforgiving (D) remorseful and guilty (E) mean-spirited and sinister 4. The grandparents’ home and furnishings signify to the children (A) elegant taste that they should strive to emulate (B) a pleasure-loving, indulgent side of their grandparents that the children seldom saw (C) evidence that God allows his faithful servants to prosper (D) a world to be approached, even cautiously sampled, but not possessed (E) all that will be theirs as soon as their grandparents die 5. Which of the following best describes the grandfather? (A) Cruel (B) Conservative (C) Deceitful (D) Long-suffering (E) Self-absorbed 10. The passage presents an ironic juxtaposition of (A) the grandfather and the grandmother (B) virtue and youth (C) innocence and egotism (D) wealth and poverty (E) Catholicism and Protestantism 6. The chief effect of such contrasts as “business matters and . . . rheumatism” (lines 10-11) and “Ste. Anne De Beaupré and Miami” (lines 12-13) is to (A) intensify the speaker’s sense of the ridiculous (B) reveal the speaker’s ambivalent attitude (C) emphasize the cynicism of the grandparents (D) reduce the grandparents to the level of low comic characters (E) glamorize the grandparents as worldly sophisticates 11. Which of the following best sums up the contrast between the attitude of the adult speaker and the attitude of the the observing child? (A) Accusatory. .awed (B) Romantic..realistic (C) Religious..secular (D) Guilty..innocent (E) Tranquil..anxious 7. The comparison of the grandfather to Galahad (line 17) is ironic primarily because the grandfather? (A) is old and ailing (B) has less pure ideals, less noble pursuits (C) recognizes no master but wealth (D) seeks little in his travels, receives no rewards at home (E) is more like a king than a knight 8. All of the following help sustain a pattern of religious imagery in the passage EXCEPT (A) “pilgrimages (lines 12) (B) “Hallowed” (line 15 (C) “vocation” (line 16) (D) “officiated” (line 43) (E) “reminiscences” (line 54-55) 9. Which of the following is the most credible reason for the kind of attention the grandmother paid to the grandchildren? (A) She had no purpose in life: she “led a relatively unjustified existence” (lines 18-19) (B) She had been mistreated so that she had a “sharper and more bellicose spirit” (line 20) (C) She had feelings of inadequacy: “She felt. . . that she was open to criticism (lines 20-21) (D) She was embarrassed by her appearance: she was an “ugly, severe old woman” (lines 42-43) (E) She was concerned about the state of their souls: her reminiscences “inspired fear and guilt” (line 57) 12. Which of the following do the children bring to their examination of the “glassed-in paintings in their huge gilt frames” (line 32)? (A) The assurance that they are civilized Christians because of the association of Italian culture with Catholicism (B) A sensitivity to the vision of great artists (C) An awareness that appearances, like gilt frames, count for little (D) The belief that Italian art is inherently religious (E) The knowledge that life in their grandparents’ home will always be as static as the figures in the paintings 13. The speaker’s attitude toward the grandparents is one of (A) bitterness tempered by maturity (B) respect strengthened by distance (C) servility imparted by discipline (D) perplexity compounded by resentment (E) gratitude made richer by love 14. The grandmother’s regard for her own conversation as “sufficiently wholesome and sustaining” (line 42) is evidence of her (A) smugness and inhospitality (B) religious prejudice (C) faith in other people (D) skill as a teacher (E) ironic sense of humor 15. The principal device used by the speaker to satirize the grandmother’s conversation (lines 46-54) is (A) mingling the serious and the trivial indiscriminately (B) including both religious and political views (C) using repetition to emphasize similar characteristics (D) introducing it with a description of the grandmother’s hospitality (E) cataloging a number of religious beliefs (45) Read the following passage carefully before you choose your answers. (5) (10) (15) (20) (25) (30) (35) (40) To his patients he gave three-quarters of an hour; and if in this exacting science which has to do with what, after all, we know nothing about – the nervous system, the human brain – a doctor loses his sense of proportion, as a doctor he fails. Health we must have; and health is proportion; so that when a man comes into your room and says he is Christ (a common delusion), and has a message, as they mostly have, and threatens, as they often do, to kill himself, you invoke proportion; order rest in bed; rest in solitude; silence and rest; rest without friends, without books, without messages, six months’ rest; until a man who went in weighing seven stone six1 comes out weighing twelve2. Proportion, divine proportion, Sir William’s goddess, was acquired by Sir William walking hospitals, catching salmon, begetting one son in Harley Street by Lady Bradshaw, who caught salmon herself and took photographs scarcely to be distinguished from the work of professionals. Worshipping Proportion, Sir William not only prospered himself but made England prosper, secluded her lunatics, forbade childbirth, penalised despair, made it impossible for the unfit to propagate their views until they, too, shared his sense of proportion – his, if they were men, Lady Bradshaw’s if they were women (she emBroidered, knitted, spent four nights out of seven at home with her son), so that not only did his colleagues respect him, his subordinates fear him, but the friends and relations of his patients felt for him the keenest gratitude for insisting that these prophetic Christs and Christesses, who prophesied the end of the world, or the advent of God, should drink milk in bed, as Sir William ordered: Sir William with his thirty years’ experience of these kinds of cases, and his infallible instinct, this is madness, this sense; in fact, his sense of proportion. But Proportion has a sister, less smiling, more formidable, a Goddess even now engaged – in the heat and sands of India, the mud and swamp of Africa, the purlieus of London, wherever in (50) (55) (60) (65) (70) short the climate or the devil tempts men to fall from the true belief which is her own – is even now engaged in dashing down shrines, smashing idols, and setting up in their place her own stern countenance. Conversion is her name and she feasts on the wills of the weakly, loving to impress, to impose, adoring her own features stamped on the face of the populace. At Hyde Park Corner on a tub she stands preaching; shrouds herself in white and walks penitentially disguised as brotherly love through factories and parliaments; offers help, but desires power; smites out of her way roughly the dissentient, or dissatisfied; bestows her blessing on those who, looking upward, catch submissively from eyes the light of their own. This lady too . . . had her dwelling in Sir William’s heart though concealed, as she mostly is, under some plausible disguise; some venerable name; love, duty, selfsacrifice. How he would work – how toil to raise funds, propagate reforms, initiate institutions! But Conversion, fastidious Goddess, loves blood better than brick, and feasts most subtly on the human will. For example, Lady Bradshaw. Fifteen years ago she had gone under. It was nothing you could put your finger on; there had been no scene, no snap; only the slow sinking, waterLogged, of her will into his. 1 2 – 104 pounds – 168 pounds 16. The speaker’s attitude toward “Proportion” and “Conversion” can best be described as one of (A) careful objectivity (B) intelligent respect (C) warm affirmation (D) elegant disdain (E) thoughtless contempt 17. The effect of the phrases “(a common delusion),” “as they mostly have,” and “as they often do” (lines 8-10), is to (A) ridicule the doctor’s diagnosis of serious human problems (B) belittle the illnesses common to mankind (C) intensify the acuity and quality of the doctor’s skill (D) reveal the doctor’s bias against religious convictions (E) emphasize the foolishness of the doctor’s patients 18. In lines 14-15, “a man who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing twelve,” the speaker suggests that the doctor’s patients (A) have benefited greatly from his medical skills (B) are not likely to suffer from delusions again (C) have gained weight in proportion to their improved health (D) are cured mentally but now suffer physical illness (E) have become heavier but not necessarily healthier 19. Of the things mentioned in the first paragraph, which of the following would the speaker probably feel was the most essential to the recovery of one’s health? (A) Routine and religious faith (B) Solitude, rest, and silence (C) Friends, books, and messages (D) A doctor with a sense of proportion (E) A doctor with a good knowledge of the nervous system 20. In the second paragraph, Lady Bradshaw is presented in terms that emphasize (A) the triviality of her accomplishments (B) her independence and self-interest (C) the gentle qualities appropriate for an aristocrat (D) her elegant style and gracious manners (E) the spirit of charity that motivates her 21. The families of Sir William’s patients approved of his treatments primarily because (A) they generally cured the patient without great cost (B) they were gentle and humane, requiring rest and good food (C) they silenced the patient and his alarming delusions (D) Sir William inspired everyone with confidence (E) Sir William’s record of cures was impressive 22. Which of the following best defines “Proportion” as the term is used by the speaker in paragraph 2? (A) Humility and self-discipline (B) Cultivated artistic sensibilities (C) The size of things, relative to other things (D) Order imposed by authority (E) The development of a healthy mind and body 23. Which of the following best describes the way in which Lady Bradshaw functions in paragraph 2? (A) A reflection of the vanities and values of her husband (B) A spokeswoman for the speaker’s opinion of the doctor (C) A messenger from the goddess of proportion (D) A defender of her husband’s patients (E) An exception to the doctor’s scheme of orderly, sensible habits 24. The chief characteristic of Sir William’s personality is (A) a marked capacity for charity (B) a weakness for the sentimental (C) a blinding self-righteousness (D) an irascible temper (E) a subtle perceptiveness 25. Which of the following does the speaker imply about Lady Bradshaw’s personality? (A) It has flourished under her husband’s guidance. (B) It has remained firm and strong in spite of pressure to change (C) It has effectively humanized her husband’s personality. (D) It is in constant conflict with and slowly poisoning her husband’s personality. (E) It is a travesty of what it could have become. 26. The chief characteristic of “Conversion” as portrayed in paragraph 3 is (A) a realistic humility and submissiveness (B) an unshakeable conviction of her own rightness (C) a radiant countenance and an air of holiness (D) a capacity to inspire self-sacrifice (E) an ability to survive and endure miserable conditions 27. In lines 63-64, “love, duty, self-sacrifice” are best understood as (A) ideals that Lady Bradshaw preaches in Hyde Park (B) virtues abandoned long ago by society (C) political slogans used in fund-raising campaigns (D) masks that hide a willful ambition (E) the code of ethics that the upper middle class lives by 28. Throughout the passage, the speaker uses Lady Bradshaw to illustrate the (A) source of Sir William’s self-confidence (B) dominance of women in Sir William’s life (C) similarity between Sir William’s two goddesses (D) effects of Sir William’s influence on others (E) sentimental aspects of Sir William’s nature 29. Throughout the passage, the speaker alerts the reader to the contrast between (A) honesty and secretiveness (B) prosperity and power (C) intelligence and creativity (D) feeling good and doing good works (E) helpful guidance and insensitive domination 30. An important aspect of the style of this passage is the use of repetitive phrases that tend to hide the subject and verb, leading to a final resolution in the syntax that produces surprise. Which of the following best illustrates this aspect? (A) “until a man who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing twelve” (lines 14-15) (B) “. . . this is madness, this sense; in fact, his sense of proportion” (lines 39-40) (C) “Conversion is her name and she feasts on the wills of the weakly” (lines 49-50) (D) “concealed . . under. . . some venerable name; love, duty, selfsacrifice” (lines 61-64) (E) “Conversion . . . loves blood better than brick” (lines 66-67) 31. Which of the following best describes the passage and its general theme? (A) A character analysis of two professional people which emphasizes the elements of idealism and selflessness that motivate them. (B) A special explication of the concepts of “proportion” and “conversion” as they are embodied in particular social classes. (C) A narrative treatment of the conflict inherent in the structure of social classes. (D) A logical analysis of the social ideals of “conversion” and “proportion” as they influence politics and religion. (E) A reasoned defense of personal values like “conversion” and “proportion” in the face of threats from unknown social forces.