Friar Lawrence: - Mrs

advertisement

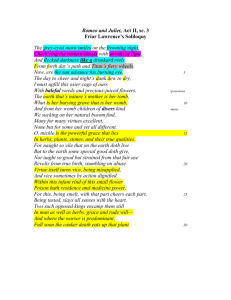

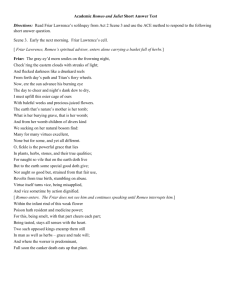

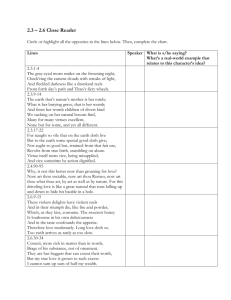

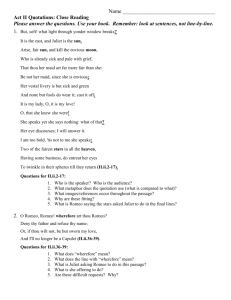

Friar Lawrence: With a friend like Friar Lawrence, who needs enemies? The Friar, a Franciscan monk in Verona, is a priest who has taken the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. As the confidante and confessor to both Romeo and Juliet, he is privy to their innermost thoughts and desires. It is the Friar who agrees to marry Romeo and Juliet in secrecy, though he knows their parents would not consent. He also concocts the plan for Juliet to play dead and is supposed to get the word out to Romeo. He fails. Nothing that Friar Lawrence touches turns out right. What are his motivations for getting so deeply involved with the star-crossed lovers? Friar Lawrence's first appearance onstage suggests a framework for understanding his character. While gardening, he contemplates the coexistence of good and evil in nature and in people. The Friar's Duality In his first appearance in the play, Friar Lawrence contemplates the balance of good and evil in all things natural. The Friar's speech suggests that good and evil exist everywhere and that nature is a precarious balance between the two. Good things can turn bad if misused, and bad things can do some good if the intent is right. This paradox sheds light on the Friar's own character and actions in the play. If he truly believes that bad can turn to good (under the right circumstances), his own deeds seem merely misguided and he becomes a victim, rather than a cause, of the tragedy. Friar Lawrence The grey-ey'd morn smiles on the frowning night, Chequering the eastern clouds with streaks of light, And flecked darkness like a drunkard reels From forth day's path and Titan's fiery wheels. Now, ere the sun advance his burning eye, The day to cheer and night's dank dew to dry, I must up-fill this osier cage of ours With baleful weeds and precious-juiced flowers. The earth that's nature's mother is her tomb; What is her burying grave, that is her womb; And from her womb children of divers kind We sucking on her natural bosom find, Many for many virtues excellent, None but for some, and yet all different. O, mickle is the powerful grace that lies In herbs, plants, stones, and their true qualities: For nought so vile that on the earth doth live But to the earth some special good doth give; Nor aught so good but, strain'd from that fair use, Revolts from true birth, stumbling on abuse. Virtue itself turns vice, being misapplied, And vice sometime's by action dignified. [Enter Romeo] Within the infant rind of this weak flower Poison hath residence and medicine power: For this, being smelt, with that part cheers each part; Being tasted, stays all senses with the heart. Two such opposed kings encamp them still In man as well as herbs, grace and rude will; And where the worser is predominant, Full soon the canker death eats up that plant. (2.3.1-30) The duality he ponders is emblematic of the Friar's own nature. If he is "virtue," then surely his good acts — helping Romeo and Juliet — turn to "vice" because he goes them the wrong way. And if his motivations are "vice" — perhaps currying favor with the Prince by helping to unite the families and end the feud — a positive result might have justified his self-interest. Unfortunately, for the Friar and everyone else involved, there is no good outcome in this tragedy. Friar Lawrence Virtue itself turns vice, being misapplied, And vice sometime by action dignified. (2.3.21-22) Romeo greets the Friar "Good morrow, father" (2.3.31), and Friar Lawrence responds by calling Romeo "young son" (2.3.33). Though these appellations are appropriate because of the religious context, this interchange has greater resonance. It is not just the exchange between the priest and the penitent. The Friar also stands in for Romeo's own father since there are no scenes between Romeo and his parents. The Friar is the only person to whom Romeo turns for advice, and he is the last person to whom Juliet turns after all others have forsaken her. In this sense, he is father to them both and responsible for upholding order. The Friar is suspicious of Romeo's sudden change of heart. He knows that Romeo has been pining for Rosaline and he tells Romeo that Rosaline did not return his love because she could tell that it "did read by rote, that could not spell" (2.3.88). Basically, he tells Romeo that he was never really in love with Rosaline and that he was just repeating empty words he didn't really understand. After such a quick turnabout, the Friar has good reason to be suspicious of Romeo's new love. Perhaps the Friar is right. But why does he agree to help Romeo? Friar Lawrence But come, young waverer, come, go with me, In one respect I'll thy assistant be; For this alliance may so happy prove To turn your households' rancor to pure love. (2.3.89-92) He consents to be a conspirator in the strange alliance because he thinks it might end the feud between the brawling households. That's a pretty bad plan and a lot to ask of a marriage — particularly a hasty and secretive one. Yet in the framework that Shakespeare has erected, the Friar's motivation might be "action dignified" (2.3.22) and can perhaps be understood as balancing vice and virtue. Obviously, he hopes that this bad plan will work out. At the same time, the Friar recognizes that the use of the sacrament of matrimony in such a stealthy manner may very well have terrible consequences. He worries that a sad ending will result. Friar Lawrence (2.6.1-2) So smile the heavens upon this holy act, That after hours with sorrow chide us not! The Friar tries to act as a voice of reason to temper the mounting hysteria as the tragedy unfolds. After slaying Tybalt, Romeo flees to the relative safety of the Friar Lawrence's cell. When Romeo bemoans his banishment and refers to it as a fate less merciful than death, the Friar seems irritated. Friar Lawrence O deadly sin! O rude unthankfulness! Thy fault our law calls death; but the kind Prince, Taking they part, hath rush'd aside the law, And turn'd that black word "death" to "banishment." This is dear mercy, and thou seest it not. (3.3.24-29) Translation: "Pull yourself together, Romeo. You're lucky you haven't been sentenced to death." The priest admonishes Romeo for behaving so melodramatically. He wants Romeo to pull himself together and behave rationally. He also tells Romeo to stop crying, to stop acting like a girl, and to count his blessings. In the Friar's Cell After he slays Tybalt, Romeo hides in the sanctuary of the Friar's cell. The Friar seems disgusted by Romeo's behavior. He tells him he is lucky not to have received a death sentence, but Romeo will not be persuaded. He feels that the Friar can't possibly understand: living without Juliet is like dying. He wishes he were dead; it would be easier. The Friar isn't impressed with these histrionics. Perhaps the Friar thinks this blubbering is similar to Romeo's overly dramatic pining for Rosaline. When the Nurse comes and reports that Juliet is also hysterical, Romeo becomes even more workedup. He wishes to kill himself because he has wounded Juliet. Then the Friar gets really irritated. He reprimands Romeo for his "unmanly" behavior and tells him he is being an idiot. He urges Romeo to pull himself together. And the Friar lists all the things Romeo has to be happy about. Juliet is alive and still loves Romeo. Tybalt wanted to kill Romeo, but Romeo killed Tybalt instead. The law decreed Romeo should die, but he has been given leniency. Then the Friar concocts the plan for Romeo to go to Juliet for the honeymoon night. He tells Romeo to go to Mantua for a little while until everything in Verona smooths over, the marriage can be announced, and Romeo can be pardoned. Is this realistic? Is the Friar just trying to calm Romeo down, or does he really believe he can make everything come out right? Friar Lawrence Enter Romeo Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo, come forth; come forth, thou fearful man. Affliction is enamour'd of thy parts, And thou art wedded to calamity. Father, what news? What is the Prince's doom? What sorrow craves acquaintance at my hand, That I yet know not? Too familiar Is my dear son with such sour company. I bring thee tidings of the Prince's doom. Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo What less than doomsday is the Prince's doom? A gentler judgment vanish'd from his lips: Not body's death, but body's banishment. Ha, banishment? Be merciful, say 'death;' For exile hath more terror in his look, Much more than death. Do not say 'banishment.' Here from Verona art thou banished. Be patient, for the world is broad and wide. There is no world without Verona walls, But purgatory, torture, hell itself. Hence 'banished' is banish'd from the world, And world's exile is death; then 'banished,' Is death mis-term'd. Calling death 'banished,' Thou cutt'st my head off with a golden axe, And smil'st upon the stroke that murders me. O deadly sin! O rude unthankfulness! Thy fault our law calls death; but the kind Prince, Taking thy part, hath rush'd aside the law, And turn'd that black word 'death' to 'banishment.' This is dear mercy, and thou seest it not. 'Tis torture, and not mercy. Heaven is here Where Juliet lives, and every cat and dog And little mouse, every unworthy thing, Live here in heaven and may look on her, But Romeo may not. More validity, More honourable state, more courtship lives In carrion flies than Romeo. They may seize On the white wonder of dear Juliet's hand And steal immortal blessing from her lips, Who, even in pure and vestal modesty, Still blush, as thinking their own kisses sin; But Romeo may not, he is banashed. Flies may do this, but I from this must fly: They are free men, but I am banished. And sayst thou yet that exile is not death? Hadst thou no poison mix'd, no sharp-ground knife, No sudden mean of death, though ne'er so mean, But 'banished' to kill me? 'Banished'? O friar, the damned use that word in hell; Howlings attend it. How hast thou the heart, Being a divine, a ghostly confessor, A sin-absolver, and my friend profess'd, To mangle me with that word 'banished'? Thou fond mad man, hear me but speak a word. O, thou wilt speak again of banishment. I'll give thee armour to keep off that word, Adversity's sweet milk, philosophy, To comfort thee, though thou art banished. Yet 'banished'? Hang up philosophy! Unless philosophy can make a Juliet, Displant a town, reverse a prince's doom, It helps not, it prevails not. Talk no more. O, then I see that madmen have no ears. How should they, when that wise men have no eyes? Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Romeo Friar Lawrence Nurse Friar Lawrence Enter Nurse. Nurse Friar Lawrence Nurse Romeo Nurse Romeo Nurse Romeo Friar Lawrence Let me dispute with thee of thy estate. Thou canst not speak of that thou dost not feel. Wert thou as young as I, Juliet thy love, An hour but married, Tybalt murdered, Doting like me and like me banished, Then mightst thou speak, then mightst thou tear thy hair, And fall upon the ground, as I do now, Taking the measure of an unmade grave. [Knocking within.] Arise; one knocks. Good Romeo, hide thyself. Not I, unless the breath of heart-sick groans, Mist-like, infold me from the search of eyes. [Knocking.] Hark, how they knock! — Who's there? — Romeo arise; Thou wilt be taken. — Stay awhile! — Stand up; [Knocking.] Run to my study. — By and by! — God's will, What simpleness is this! — I come, I come! [Knocking.] Who knocks so hard? Whence come you? What's your will? [Within.] Let me come in, and you shall know my errand. I come from Lady Juliet. Welcome, then. O holy friar, O, tell me, holy friar, Where is my lady's lord, where's Romeo? There on the ground, with his own tears made drunk. O, he is even in my mistress' case, Just in her case! O woeful sympathy! Piteous predicament! Even so lies she, Blubbering and weeping, weeping and blubbering. Stand up, stand up; stand, an you be a man. For Juliet's sake, for her sake, rise and stand! Why should you fall into so deep an O? Nurse! Ah, sir, ah, sir! Death's the end of all. Spak'st thou of Juliet? How is it with her? Doth she not think me an old murderer, Now I have stain'd the childhood of our joy With blood remov'd but little from her own? Where is she? And how doth she? And what says My conceal'd lady to our cancell'd love? O, she says nothing, sir, but weeps and weeps, And now falls on her bed, and then starts up, And Tybalt calls, and then on Romeo cries, And then down falls again. As if that name, Shot from the deadly level of a gun, Did murder her, as that name's cursed hand Murder'd her kinsman. O, tell me, friar, tell me, In what vile part of this anatomy Doth my name lodge? Tell me, that I may sack The hateful mansion. [Drawing his sword.] Hold thy desperate hand! Art thou a man? Thy form cries out thou art; Thy tears are womanish, thy wild acts denote The unreasonable fury of a beast. Unseemly woman in a seeming man, And ill-beseeming beast in seeming both! Thou hast amaz'd me. By my holy order, I thought thy disposition better temper'd. Hast thou slain Tybalt? Wilt thou slay thyself? And slay thy lady that in thy life lives, By doing damned hate upon thyself? Why rail'st thou on thy birth, the heaven, and earth, Since birth, and heaven, and earth, all three do meet In thee at once, which thou at once wouldst lose? Fie, fie, thou sham'st thy shape, thy love, thy wit, Which, like a usurer, abound'st in all, And usest none in that true use indeed Which should bedeck thy shape, thy love, thy wit. Thy noble shape is but a form of wax, Digressing from the valour of a man; Thy dear love,sworn but hollow perjury, Killing that love which thou hast vow'd to cherish; Thy wit, that ornament to shape and love, Misshapen in the conduct of them both, Like powder in a skilless soldier's flask To set a-fire by thine own ignorance, And thou dismember'd with thine own defence. What, rouse thee, man! Thy Juliet is alive, For whose dear sake thou wast but lately dead; There art thou happy. Tybalt would kill thee, But thou slew'st Tybalt; there art thou happy. The law that threaten'd death becomes thy friend And turns it to exile; there art thou happy. A pack of blessings light upon thy back; Happiness courts thee in her best array; But, like a mishaved and sullen wench, Thou pout'st upon thy fortune and thy love. Take heed, take heed, for such die miserable. Go, get thee to thy love, as was decreed; Ascend her chamber, hence and comfort her. But look thou stay not till the watch be set, For then thou canst not pass to Mantua, Where thou shalt live, till we can find a time To blaze your marriage, reconcile your friends, Beg pardon of the Prince, and call thee back. With twenty hundred thousand times more joy Than thou went'st forth in lamentation. Go before, nurse. Commend me to thy lady, And bid her hasten all the house to bed, Which heavy sorrow makes them apt unto. Romeo is coming. (3.3.1-158) All of this advice makes sense, but then the Friar suggests something strange. After counseling Romeo to stop behaving in such a melancholy manner, he tells him to go to Juliet for his honeymoon night, and then straight to Mantua to fulfill the Prince's edict of exile. He says that Romeo can come back to Verona when the coast is clear. This advice is a marked difference from the advice the Nurse gives to Juliet. The Nurse counsels Juliet to give up Romeo and go for Paris instead. She thinks it is a safer and better choice for Juliet. But the Friar tells Romeo to consummate the marriage before leaving for Mantua. Going to the Capulet home was risky before Tybalt's death. After his banishment, being discovered at the Capulet home is a certain death sentence for Romeo. The Friar's advice leaves the audience wondering whose interest he is watching at this point. Is he looking out for Romeo, Juliet, or himself? Does he want to make sure this union is consummated so the two feuding households must unite? Why Does the Marriage Need to Be Consummated? In Catholicism, a marriage can be annulled (ended) if it has not been consummated. Romeo kills Tybalt and is banished before he and Juliet consummate their vows. Had they not spent the night together, the marriage could have been annulled. The Nurse thinks Juliet could still marry Paris, and she is right technically (although Juliet loves Romeo.) The Friar, however, sends Romeo to consummate his union before he leaves for Mantua. This action eliminates the possibility for annulment. Why is the Friar making sure that the marriage lasts? The bad advice keeps coming. When Juliet turns to Friar Lawrence in desperation because her parents are forcing her to marry Paris, the Friar concocts the crazy scheme for Juliet to feign her own death. He tells her that if she has the strength to take her own life rather than marry Paris, than she should have the strength to pretend she's dead to avoid the shame of the second wedding. Friar Lawrence Hold, daughter. I do spy a kind of hope, Which craves as desperate an execution As that is desperate which we would prevent. If, rather than to marry County Paris, Thou hast the strength of will to slay thyself, Then is it likely thou wilt undertake A thing like death to chide away this shame, That cop'st with Death himself to 'scape from it; And, if thou dar'st, I'll give thee remedy. (4.1.68-76) Is faking death a "vice sometime by action dignified" (2.3.22)? How can the Friar believe that this sort of deception is a good idea? He suggests that Juliet lie to her parents by consenting to marry Paris and then drink the sleeping potion. It gets worse. Why Does Shakespeare Dis the Friar? Romeo and Juliet ends with Friar Lawrence looking pretty responsible for the deaths of the play's protagonists. Is it possible that Shakespeare placed the blame on the Catholic priest because of the general attitude toward Catholicism and its clergy during the reign of Queen Elizabeth? This idea may seem like a bit of a stretch at first, but a closer look reveals that it has some merit. Being a Catholic under Elizabeth was not officially illegal, but any form of practiced Catholicism was. Thus, it was against the law to go to Mass, to make confession, to be married by a priest, and to actively practice the religion in any number of other ways. Lands owned by Catholic parishes were confiscated and made the property of the monarch, who was also the head of the Church of England. Most appalling, however, was the systematic persecution of Catholic dissenters in Elizabethan England. Ostensibly convicted of treason against England, Catholics could be tortured and even executed for not conforming to the Anglican Church. One historian estimates that 189 Catholics — 128 of them priests — were tortured at the Tower of London during Elizabeth's rule. Another source adds that 32 Franciscans, the order to which Friar Lawrence belonged, were starved to death in England at this time. So while Shakespeare avoids an overt anti-Catholic sentiment in Romeo and Juliet, it is certainly possible to understand why his audience may have readily accepted the implication that the bumbling priest deserves to be blamed for the lovers' deaths. In the play's grim final scene, Friar Lawrence discovers the bodies of both Paris and Romeo. He then turns to the awakening Juliet and advises her that he'll help her escape to a convent. He is desperate that she leave the tomb before she is discovered. Is the Friar worried about Juliet, or does he fear that his own role in the tragedy will be discovered when the truth comes out? Friar I hear some noise. Lady, come from that nest Lawrence Of death, contagion, and unnatural sleep. A greater power than we can contradict Hath thwarted our intents. Come, come away. Thy husband in thy bosom there lies dead; And Paris too. Come, I'll dispose of thee Among a sisterhood of holy nuns. Stay not to question, for the watch is coming. Come, go, good Juliet. [Noise again.] I dare no longer stay. Exit (5.3.151-59) Does the Friar Try to Save His Own Skin? By the time Juliet has drunk the potion, Friar Lawrence is in too deep. He continues to "dignify vice" when he pretends to believe that Juliet is dead in her bedroom. He lies to the grief-stricken parents and tells them to prepare Juliet for the church. It seems heartless to keep the truth from this grieving family, but Friar Lawrence takes deception one step further. He tells the Capulets that Juliet is better off dead because her ascent to heaven is an even greater glory than the marriage they had planned for her. Friar Lawrence Heaven and yourself Had part in this fair maid; now heaven hath all, And all the better is it for the maid. Your part in her you could not keep from death, But heaven keeps his part in eternal life. The most you sought was her promotion, For 'twas your heaven she should be advanc'd; And weep ye now, seeing she is advanc'd Above the clouds, as high as heaven itself? O, in this love, you love your child so ill That you run mad, seeing that she is well. (4.5.66-76) It's interesting that the Friar mentions the marriage to Paris in this context. Perhaps he is trying to justify his own motives. If he believes that this scenario is truly better than a second marriage to Paris, then maybe he does believe that Juliet is better off dead. The Friar does worry about Juliet's fate when he learns that Friar John has been unable to deliver the message (about Juliet's faked death) to Romeo. Friar Lawrence Now must I to the monument alone. Within this three hours will fair Juliet wake. She will beshrew me much that Romeo Hath had no notice of these accidents; But I will write again to Mantua, And keep her at my cell till Romeo come -Poor living corse, clos'd in a dead man's tomb! [Exit.] (5.2.24-30) Though he is concerned that Juliet will wake up in the crypt, the Friar thinks only in terms of his next strategy, which will include more deception. This situation is already a mess and it is unclear if the Friar takes any of the blame upon himself. When Juliet declines his counsel to flee, Friar Lawrence decides to save himself. He runs away leaving Juliet alone in the tomb. But, he doesn't get very far. The watchman apprehends the Friar, who is still holding the crowbar and spade in his hands. The Prince demands that Friar Lawrence explain himself and the bloody scene. Friar All this I know, and to the marriage Lawrence Her nurse is privy; and, if aught in this Miscarried by my fault, let my old life Be sacrific'd, some hour before his time, Unto the rigour of severest law. (5.3.265-69) The Friar tells the whole sad tale and concludes by implicating the Nurse and himself in the debacle. He does not apologize for his role, but says that if anything that has transpired is his fault, he should be punished. If? That's a big question. Though Prince Escalus does not punish the Friar, the audience must decide whether such leniency is appropriate. Apparently, the Friar still believes that his actions were justified. What do you think: Is the play’s tragic ending Friar Lawrence’s fault?