Weight Gain - Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences

advertisement

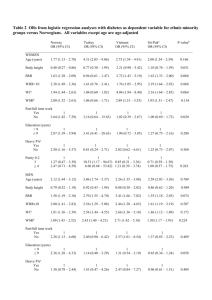

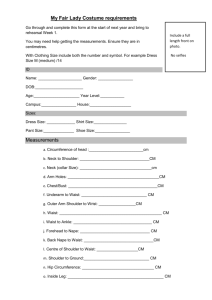

Weight gain Over half (54%) of the adult Australian population are overweight or obese (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007), up from 45% a decade ago. People with low incomes and education levels, from rural areas and male are more likely to be overweight and obese (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007). Catapano and Castle (2004) report that individuals with schizophrenia are three times more likely to be obese than the general population. Being overweight or obese poses a major risk to the long term health of people with a mental illness by increasing their risk of chronic illness (Marder et al., 2004) and appears to lessen life expectancy markedly, especially among younger adults (Fontaine, Redden, Wang, Westfall, & Allison, 2003). Psychotropic medications contributing to weight gain Anti-psychotics Atypical Highest risk Clozapine Olanzapine Moderate risk Risperidone Minimal risk Ziprasidone Typicals Chlorpromazine – dose dependent Mood stabilisers Lithium (more than half on long term treatment gain weight) Chen and Silverstone (1990) cited in Malhi, Mitchell and Caterson (2001). Sodium valproate Antidepressants Tricyclic Amitriptyline Imipramine MAOI phenelzine Other factors contributing to weight gain in individuals with a mental illness Diet high in fat and low in fibre (Brown, Birtwistle, Roe, & Thompson, 1999) Lack of exercise (Brown, Birtwistle, Roe, & Thompson, 1999) – sedentary lifestyle, may have to stop work due to symptoms, restricted activity due to hospitalisation or pharmacotherapy Hypothyroidism (mood stabilisers can produce thyroid dysfunction) Family history of obesity or diabetes (Marder et al., 2004) Patho-physiology of weight gain Obesity is caused by a calorie intake which exceeds energy output. Saturated fats and high sugar levels in food are high calorie while a sedentary life style will not burn up the high calorie intake thus the excess is stored as adipose tissue or fat. In addition a family history of obesity, impaired endocrine function (hormones), fluid retention and psychotropic medication all contribute to weight gain see figure 1. Figure 1. Factors important in maintaining weight and the effects of psychotropic medications. (Malhi, Mitchell, & Caterson, 2001, p. 316) MAOIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants. + facilitation; - inhibition Physical health risks of obesity Obesity is associated with increased rates of: Osteoarthritis (increased weight on weight bearing joints exacerbates arthritis resulting in pain which in turn leads to reduced activity) Sleep apnoea (increased risk with BMI of 30 or greater) Gallbladder disease Liver disease Polycystic ovarian disease Cancer (oesophageal, colon, endometrial, kidney, breast) Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Cardiovascular disease (CVD) Hypertension Stroke Hyperlipidemia Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and Metabolic syndrome Metabolic syndrome is a collection of factors (excess abdominal fat, high blood pressure, abnormal blood cholesterol and fats, abnormal blood sugar metabolism) which combine to increase the risk of T2DM and CVD (Lumby, 2007). Weight related illnesses are also increased in those who smoke Psychological health risks of obesity Altered body image Depression Restricted lifestyle and quality of life Significant factor in non compliance with psychotropic medication thus increasing the risk of relapse Assessment There are 3 main measures including the Body Mass Index (BMI), waist circumference and the waist to hip ratio (WHR). Measuring the Body Mass Index (BMI) Weight (kilograms) ÷ Height (metres) squared or Weight (pounds) ÷ Height (inches) squared X 704.5 Online BMI Calculator: Better Heath Channel Victoria http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/bhcv2/bhcsite.nsf/pages/bmijs The BMI is more reliable than scales because weight varies with height Classification of body fatness based on BMI BMI Classification ≤ 18.5 Underweight 18.5 – 24.9 Healthy 25.0 – 29.9 Overweight 30 – 39.9 Obese ≥ 40.0 Morbidly obese (World Health Organisation, 2000) Measuring the waist circumference and the waist to hip ratio (WHR) The location of fat is more important than the BMI. The waist circumference and specifically the waist to hip ratio (WHR) are a better indicator of the risk for heart disease, as even small increases in the WHR increases the risk of heart disease by accelerating atherosclerosis (joAcardiology). The WHR is a measure of how much weight is around the abdomen as opposed to the hips. Run a tape measure around the waist at the narrowest point (usually just above the umbilicus (belly button), after breathing out and do not hold in the stomach, then run tape around the hips at the widest point (usually around the bony prominences). Divide the waist circumference by the hip circumference to get the WHR. Waist to Hip Calculator: MyDr http://www.mydr.com.au/tools/ToolFrame.asp?ToolId=44 The ideal WHR in men is 0.90 or less and 0.80 or less in women. Level of health risks associated with waist circumference in white men/women Men Women Health risk* < 94 cm < 80 cm Low ≥ 94 – 101.9 cm ≥ 80 – 87.9 cm Increased ≥ 102 cm ≥ 88 cm High * Risk for type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, or hypertension. Asians and Indians cut off 10 cm lower (World Health Organisation, 2000) Comparison of relative strengths and weaknesses of BMI versus Waist circumference BMI Waist circumference Predictor of total body fat and related Predictor of total body fat and related health risks at a population level health risks at a population level Weak relation to visceral fat Best simple marker for visceral fat Modest predictor of multiple health risks in Strongest predictor of multiple health risks individuals in individuals Large existing data bases Data bases accumulating rapidly Less reliable in discriminating health risk Less reliable in discriminating health risk when BMI < 30 when BMI > 40 Potentially confounded by differences in Larger measurement error than BMI muscle mass Requires shoes off Requires upper clothing off Sex differences ignored Cut-offs different for men and women Needs calculation or chart for clinical use; Easy home monitoring (no calculation is conceptually complex needed); is easily understood (Han, Sattar, & Lean, 2006, p. 698) Prevention (avoidance of weight gain) Focus on prevention as “subsequent weight loss is very difficult to achieve and existing interventions to promote weight loss are often ineffective” (Marder, et al., 2004, p. 1336). Take a full health history – if patient has a family history of obesity, diabetes or has a BMI of 25 or higher, the prescriber should consider the weight gain profile of different medication (Marder, et al., 2004) before prescribing. Monitor and chart the BMI and waist circumference of every patient on psychotropic medication. For those on medication’s known to be associated with weight gain, weigh, measure and chart at each outpatient visit (or admission) for 6 months, or after any medication change. Encourage the patient to monitor and chart their own measurement and weight. Unless a patient is underweight (BMI ≤ 18.5), a weight gain of one BMI unit indicates the need for an intervention. If the waist circumference is ≥ 102 cm (men) or ≥ 88 cm (women) an intervention is needed (Marder et al., 2004). Aim to maintain therapeutic effects while minimising weight gain and consider substituting with a suitable antipsychotic with a low weight gain profile. This is not always straightforward as the following personal account illustrates. Personal Perspective: Olazepine induced weight gain “It did settle my psychotic symptoms a bit but not totally, I still experienced delusional thinking, and my voices never went away entirely anyway. But what I noticed was I started putting on weight. I'd go out with friends to restaurants and stuff and I would invariably eat more than anyone else at the table, I just had this ravenous appetite I just couldn't control. And then I asked my doctor if I could change because I was really concerned about running around the hockey field like an elephant, and she said fine, fine, no worries. I went on to Abilify and that was disastrous…That was two years ago and it actually sent me more psychotic than I already was, and I went into a mania, chronic insomnia. It was the most awful experience, I have to say, and since that time, two years ago, I've been very, very unwell for the entire two years, with lots of psychosis and depression and you name it, I've had it. It's been a mind hell…I blame myself for wanting to change the medication in the first place and upsetting the whole stability I sort of had? I sort of blame myself. But then what's wrong with wanting to look at your body weight and your body image, now we are driven by body image in this society? Because I felt really bad, I felt cumbersome in my own body, I hated it. So I did change but it was disastrous, absolutely disastrous. And now I'm on Clozapine… I sort of describe it as the monster got out of its cage, the monster Madness got out of its cage, and I haven't been able to put it back in and secure the lock to lock it away. It keeps creeping from its cage and ... plus melancholia has emerged as well and she sort of trails behind me in her dowdy gown, you know, waiting to assail me with her darkness and her drear drear horrible nothingness. I keep wondering, when is it going to stop, when will I wake up one morning and feel OK about getting up? It's really, really awful, I feel as though I've gone back 30 years” (Jeffs, 2007). Management: Reducing weight gain A multidisciplinary approach is recommended Mortality and morbidity can be reduced by the loss of 5% to 10% of body weight. If the WHR is over the recommended limits a medical review by a General Practitioner (GP) is indicated. Address issues underlying weight gain for example, if weight gain is related to medication reduce the dose to minimise weight gain while maintaining therapeutic effect or substitute with another psychotropic. Educate the patient and carers on how to implement lifestyle changes. Patients are often economically disadvantaged and need low cost or no cost programs Caloric reduction diet of 5 or more servings of fresh food and vegetables daily and reduce saturated and trans fatty acid intake ≤ of total energy intake (National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2007). Regular exercise by gradually building up tolerance to at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise for most days of the week (National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2007). Reduction in alcohol intake Self monitoring, stress management and cognitive restructuring Bolster self-efficacy Emotional and moral support Weight loss medications are a last resort as they may reduce the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication (Green, Canuso, Brenner, & Wojcik, 2003). Severe cases surgical intervention may be considered. Conclusion Weight gain is common and a significant health hazard. Psychotropic medications and the unhealthy lifestyles of people with a mental illness both contribute to weight gain. The focus on management is prevention as once weight has been gained it is very difficult to lose, however even small reductions can result in improved morbidity and mortality. Weight management programs require a multidisciplinary approach to maximise successful outcomes. References Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). Overweight and obesity (No. 4102.0). Canberra. Brown, S., Birtwistle, J., Roe, L., & Thompson, C. (1999). The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine, 29(3), 697-701. Catapano, L., & Castle, D. (2004). Obesity in schizophrenia: What can be done about it? Australasian Psychiatry, 12(1), 23-25. Fontaine, K. R., Redden, D. T., Wang, C., Westfall, A. O., & Allison, D. B. (2003). Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA, 289(2), 187-193. Green, A. I., Canuso, C. M., Brenner, M. J., & Wojcik, J. D. (2003). Detection and management of comorbidity in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26(1), 115-139. Han, T. S., Sattar, N., & Lean, M. (2006). ABC of obesity. Assessment of obesity and its clinical implications. BMJ, 333(7570), 695-698. Jeffs, S. (2007). The Zyprexa story. All in the mind. ABC Radio National, from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/allinthemind/stories/2007/1860792.htm Lumby, B. (2007). Guide schizophrenia patients to better physical health The Nurse Practitioner, 32(7), 30-37. Malhi, G. S., Mitchell, P. B., & Caterson, I. (2001). 'Why getting fat, Doc?' Weight gain and psychotropic medications. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(3), 315-321. Marder, S. R., Essock, S. M., Miller, A. L., Buchanan, R. W., Casey, D. E., Davis, J. M., et al. (2004). Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(8), 1334-1349. National Heart Foundation of Australia. (2007). Reducing risk in heart disease 2007 World Health Organisation. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic (No. 894). Geneva: WHO.