M&M`s Adaptation Lab

advertisement

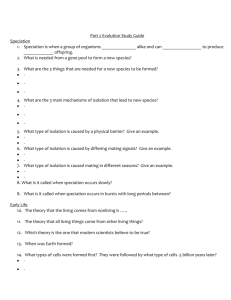

Natural Selection and Speciation Lab Speciation: What are species anyway, and how do new ones evolve? Defining a species A species is often defined as a group of individuals that actually or potentially interbreed in nature. In this sense, a species is the biggest gene pool possible under natural conditions. For example, these happy face spiders look different, but since they can interbreed, they are considered the same species: Theridion grallator. Also, many plants, and some animals, form hybrids in nature. Hooded crows and carrion crows look different, and largely mate within their own groups — but in some areas, they hybridize. Should they be considered the same species or separate species? QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Defining speciation Speciation is an event that produces two or more separate species. Imagine that you are looking at a tip of the tree of life that constitutes a species of fruit fly. Move down the tree to where your fruit fly twig is connected to the rest of the tree. That branching point, and every other branching p;oint on the tree, is a speciation event. At that point genetic changes resulted in two separate fruit fly lineages, where previously there had just QuickTime™ and a decompressor been one lineage. But why and how did it happen? are needed to see this picture. Causes of speciation Geographic isolation In the fruit fly example from our notes, some fruit fly larvae were washed up on an island, and speciation started because populations were prevented from interbreeding by geographic isolation. Scientists think that geographic isolation is a common way for the process of speciation to begin: rivers change course, mountains rise, continents drift, organisms migrate, and what was once a continuous population is divided into two or more smaller populations. It doesn't even need to be a physical barrier like a river that separates two or more groups of organisms — it might just be unfavorable habitat between the two populations that keeps them from mating with one another. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Question: How do different habitats affect speciation? Purpose: The purpose of this investigation is to model speciation through geographic isolation. Materials: 5 small pieces of paper of each color = ”the prey” 1 piece of fabric=”the habitat” 1 lab bin to hold small paper pieces Methods: 1. In a group of 4-5 people, pick 1 GAME WARDEN. The remaining people will be PREDATORS. 2. Record who in your group holds each job: GAME WARDEN ________________ HUNTERS ________________________________________________________ 3. Spread the fabric out on your team’s table. This will be your “prey’s’” habitat. 4. Have the HUNTERS turn around as the GAME WARDEN spreads out the “animals” in the habitat. Keep in mind: Do not group the animals by color, they should be mixed up Do not put the animals in rows or a pattern. 5. Have the HUNTERS turn back around to face the habitat and pick the first animals that they see within 20 seconds. 6. Count how many of each color survived and fill in the chart under “Surviving Population Generation 1.” 7. In this simulation, every survivor will have 2 offspring for the next generation. The baby animals will be the same color as the parent animal. Fill in how many offspring of each color you obtain under Offspring Generation 1. 8. Add the “Offspring” + “Surviving” to figure out how many total of each color you now have, and fill in the appropriate column. 9. Have the HUNTERS again turn away as the GAME WARDEN spreads out the surviving animals and their offspring on the fabric. 10. Repeat steps 5 through 9 filling out the 2nd and 3rd generation part of the chart. Results: 1) Which color had the most survivors the after the 1st hunt? Which color had the most survivors the after the 2nd hunt? After the 3rd hunt? 2) Which color is best adapted for this environment? How do you know? 3) Which is least adapted for this environment? How do you know? 4) Which colors are at risk for becoming extinct if you continued to play? Why? 5) Which colors would become more prevalent if you continued to play? Why? 6) Compare your data to the data of another habitat. What were the similarities? What were the differences? In your opinion, did this lab show evidence of speciation due to geographical isolation?