Appendix A: Criteria for Graphing Scientific Data

advertisement

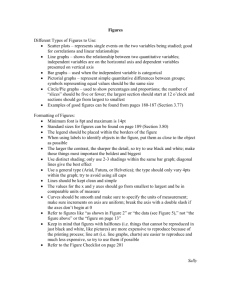

Appendix A: Criteria for Graphing Scientific Data Often the first step in analyzing the results of an experiment is the presentation of the data in the form of a graph. A graph is a visual representation of the data, which assists in bringing out and finding the possible relationship(s) between the independent and dependent variables. Examination of a graph makes it much easier to see the effect the independent variable has on the dependent variable(s). Accurate and clearly constructed graphs will assist in the interpretation and communication of your data, and when presenting a well-documented argument supporting or falsifying your hypothesis in the final steps of a scientific investigation. All graphs should be easy to interpret and labeled fully. The following guidelines will help you construct a proper graph. Graphing tips 1) Use graph paper of a high quality. 2) A ruler should be used to draw axes and to plot data neatly and accurately. 3) Always graph the independent variable on the x-axis (horizontal axis), and the dependent variable on the y-axis (vertical axis). 4) The scales of the axes should be adjusted so that the graph fills the page as much as possible. The axes often, but not always, start at zero. Choose your intervals and scales to maximize the use of the graph paper. Intervals should be logically spaced and easy to interpret when analyzing the graph (e.g. intervals of 1’s, 5’s, or 10’s are easily interpreted, but non-integer intervals (e.g. 3.25’s, 2.33’s, etc.) are not. To avoid producing a graph with a lot of wasted space a discontinuous scale is recommended for one or both scales if the first data point is a large number. Simply add two tic marks between the zero and your lowest number on one or both axes to show that the scale has changed. 5) Label both axes to indicate the variable and the units of measure. Write the specific name of the variable. Do not label the axes as the dependent variable and independent variable. Include a legend if different colors are used to indicate different aspects of the experiment. 6) Graphs (along with drawings, and diagrams) are called figures and are numbered consecutively throughout a lab report or scientific paper. Each figure is given a number, a title that describes contents, and an informative sentence giving enough information for the figure to be understandable apart from the text (e.g. Figure 1. Temperature and Leaf Color Change. The relationship between the change in vine maple leaf color and changes in ambient temperature). Generally, this information is placed below the figure or graph. 7) Choose the type of graph that best presents your data. Line and bar graphs are the most common. The choice of graph type depends on the nature of the variable being graphed. Line Graphs are used to graph data that only involves continuous variables. A continuous variable is capable of having values over a continuous range (i.e. anywhere between those that were measured in the experiment). For example, pulse rate, temperature, time, concentration, pH, etc. are all examples of continuous variables. See figure 1 on the next page. Biology 100 Laboratory Manual 1 Revised Summer 2004 Making Line Graphs 1) Plot data as separate points. Make each point as fine as possible and then surround each data point with a small circle. If more than one set of data is plotted on the same graph, distinguish each set by using circles, boxes, triangles, etc. 2) Generally, do not connect the data points dot to dot. Draw smooth curves, or if there appears to be a linear relationship between the two variables, draw a line of best fit. 3) If more than one set of data is plotted on a graph, provide a key of legend to indicate identify each set. Label the graph as a figure, give it an informative title, and a descriptive sentence. Rate of lactose digestion (mg lactose/min.) 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 0.0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0 8.0 9.0 pH of solution Figure 1. pH effects on lactase. Note that a line graph was used to graph the data because both variables, pH and the rate of digestion, are continuous variables. Bar Graphs are used if the data involves a discrete variable (non-continuous variable). A discrete variable, unlike a continuous variable, cannot have intermediate values between those measured. For example, a bar graph (Figure 2, below) would be used to plot the data in an experiment involving the determination of chlorophyll concentration (chlorophyll concentration is a continuous variable) found in the leaves of different tree species (The discrete variable is the species of tree). Bar graphs are constructed using the same principles as for line graphs, except that the vertical bars are drawn in a series along the horizontal axis (i.e. x-axis). In the example below, a bar graph was used to graph the data because tree species is a discrete variable since it is impossible to have a value or species between those used. Chlorophyll concentration (mg / gram of leaf ) 8.0 7.0 6.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 Dogwood Vine Maple Red Alder Figure 2. Chlorophyll Concentrations. The chlorophyll concentrations were measured mg/grams of leaf in the leaves of three tree species. Biology 100 Laboratory Manual 2 Revised Summer 2004