Healthy Beginnings: Developing perinatal and infant mental

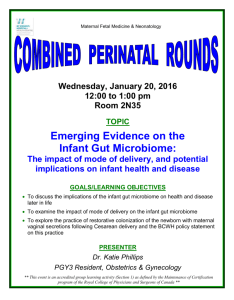

advertisement