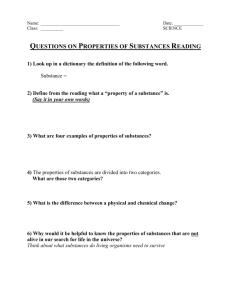

table 1: initial screening criteria for a potential pop

advertisement

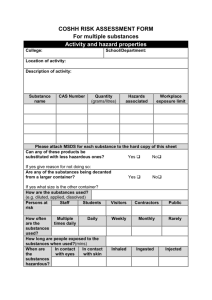

Technical Issue Brief II WWF Paper Prepared for Delegates’ Consideration at POPs INC3 August 1999 PERSISTENT ORGANIC POLLUTANTS: CRITERIA AND PROCEDURES FOR ADDING NEW SUBSTANCES TO THE GLOBAL POPS TREATY persistence in water, the bioaccumulation potential of the substance based on its log Kow, and the toxic properties of the substance. PART I: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND This briefing follows an earlier Technical Issue Brief on criteria and procedures published by WWF in March 1999, after the first meeting of the Criteria Expert Group (CEG1) held in Bangkok in 1998. It outlines recommendations for dealing with several issues which were not resolved at the second and final meeting of the Criteria Expert Group (CEG2), which was held in Vienna in June 1999. Further international negotiations on these matters will take place at the third meeting of the POPs Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC3) to be held in September 1999 in Geneva. Another issue which is likely to discussed at INC3 is where the precautionary principle should feature in the treaty. This was the topic of some heated debate at CEG2, and it is of vital importance because it will determine how much weight is actually given to the precautionary principle. Important procedural issues will no doubt be further debated at INC3. These include issues such as how other Parties and NGOs and IGOs can be kept informed of a substance’s progression in the system once it has been nominated for consideration as a POP under the treaty, and how those other Parties and observers can provide further data to support (or contradict) a proposal to designate a substance as a POP. There is also likely to be some discussion at INC3 about how to deal with data gaps on suspect chemicals. One of the most important areas to be addressed at INC3 will be the scope of the treaty, and particularly whether it will include compounds which undergo regional rather than global transport. Another issue relating to the scope of the treaty, which may be re-opened at the INC3, is whether organometallic compounds will be able to be included as future POPs under the treaty. WWF’s views on these issues are detailed below under the following four headings: scope of the treaty; screening criteria; the precautionary approach; and procedural issues. While recommendations are presented as the issues are addressed in the text, the complete list of recommendations are also appended as an annex at the end of this report. Some other criteria for identifying future POPs also need to be finalized. For example, with regard to the initial screening criteria to identify future potential POPs under the treaty, the three criteria which were not agreed at CEG2 included those relating to the substance’s 1 c) [Environmental transport of a substance on a global or transregional scale such that global action is warranted;] PART II: SCOPE OF THE TREATY Long Range Environmental Transport Some countries want to be able to bring substances which are transported within regions under the scope of the treaty, rather than to restrict it to only those pollutants which undergo global transport of several hundred miles. However, other countries prefer that the treaty embrace substances which are at least transported across regional boundaries, but only when this causes a problem in several regions, or when regional agreements have not been able to deal with the problem. These definitions may look similar in that all require less than global movement, but there are significant differences. In definition (a), proposed by the Swedish delegate, the substance could be transported just within regions, although not just short distances as the transport would have to be on a regional scale. This implies distances at least greater than neighboring countries and potentially up to regional boundaries. However, as a clarification, Sweden felt that regional transport should include substances which led to environmental exposure at distances more than 100 kilometers from the source of release. In this option, even if the substance did not cross regional boundaries, but it was transported within several regions, the substance would best be controlled by taking global action. This definition could potentially allow countries access to global legislation to control the polluting activities of countries up-river from them. The EU countries include the main proponents for including regional transport and highlighted that according to the Governing Council decision 19/13C, paragraph 9, the “potential for regional and global transport” should be taken into account. The need to consider regional and global transport is also repeated in the terms of reference of the CEG. This matter will need to be resolved by the INC. By the end of the CEG, three definitions of long range environmental transport were in square brackets, indicating lack of consensus (paragraph 51, UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3): In definitions (b) and (c) the substance must move beyond one region. In definition (b) action could focus on substances causing transregional problems if regional action by itself was not sufficient, for any reason. It could, for example, include cases where bilateral regional action was attempted but was not successful because one region was not willing to take action. Alternatively, it could require action if two or more regions were involved, and one or more of them did not have the domestic legislative capabilities or lacked the necessary a) [Environmental transport of a substance on at least a regional scale occurring in different regions of the world;] b) [Environmental transport of a substance globally or trans-regionally and at a distance where regional action is not sufficient alone to address the problem;] 2 regulatory authorities to take action. In definition (c), action within the global treaty would only take place if multiple regions were involved, and they were willing to take action on a global scale. This definition implies the involvement of more than two regions. there were problems in some other areas. It was argued that regional problems would be better addressed at a more local scale, as required by the principle of subsidiarity. The case of nonyl phenol ethoxylates was used as an example, since the EU might be considering regulating these substances, but they were not considered to be a serious problem in the U.S. Arguing in support of including substances with just regional transport, the Netherlands delegate used the analogy of the “well” theory, noting that it was best to cover the well before the child fell in. He noted that many of the chemicals currently ear-marked for global controls had been in use for around 50 years and during this time their ability to be transported globally had gradually become apparent. However, a chemical which had been used for a shorter period and which had already become a regional problem, might, in time, become a global problem - but it was better to take action before it did. The PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl ethers) were used as an example, since these flame retardants are now found in most areas of the globe, but it would be difficult to prove that there was global transfer because they are so widely used and goods containing them are found throughout the globe. To support this argument it was noted that with DDT it had only become absolutely clear that global transfer had occurred after it had been banned in certain areas and subsequently found in areas remote from existing sources. Austria raised a pertinent question as to what was the usual definition of a region. It was suggested that it would be up to the INC to agree on such a definition, although it was thought to be perhaps smaller that the five regions of the UN. WWF Recommendation No. 1: Substances causing regional problems in several areas should be able to be covered under the treaty, even if there is no proof of environmental transport on a global scale. Organo-metallic Substances Organic compounds are generally defined in chemistry textbooks as compounds that contain carbon and in some cases other elements as well. If this definition were to be embraced in the treaty, then organometal compounds could come within its remit. Consistent with this approach, the final report of CEG2 stated that it was “agreed that organo-metallic chemicals were organic chemicals and therefore fell within the scope of the future convention” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3). Provided this issue is not re-opened during INC consideration, this will stand as the official guidance, such that organo-metallic compounds can be proposed for inclusion in the treaty. The U.S. was against allowing pollutants to be covered by the global treaty if the substances were only causing regional problems, arguing that it would infringe on national sovereignty if a country were to lose the ability to use a chemical with which it had no problems just because 3 In support of the arguments for the value of 2 months WWF notes the following: WWF Recommendation No. 2: Organometal compounds should be able to be added to the treaty in future. 1. Data shown in Table 2, page 15 indicate that it is not strictly correct that the water half-life data for all existing POPs far exceeds 6 months. 2. Since water is a transport medium, the half-life should be more comparable to the half life in the other transport medium, namely, air. As an approximate rule, which is used in the prediction of oil spills, water in the upper few meters of the water column moves at 2.5 - 3.0% (i.e. 1:33 or 1:40) of the wind speed, and lipophilic (fatloving) pollutants implicated in global transfer may be found in the surface micro-layer. Therefore, a pollutant which traveled two days in air might be expected to travel the same distance in 66-80 days in the upper layers of the ocean. This ratio is noted in several publications including the UK Ministry of Defence Hydrographic Department publication on Ocean Passages for the World (1973) which puts forward an average empirical value of about 1:40 for the ratio of the speed of the surface current and the speed of the wind responsible. 3. The UN ECE POP protocol lays down a half-life in water of greater than 2 months as a criterion. 4. Persistence can vary according to climatic conditions. For example, chemicals are liable to persist longer in colder countries, where the summer season is short, because this leads to reduced breakdown in water (hydrolysis). Similarly, chemicals may persist longer in the more acidic waters that are found in Finland. For a POP, PART III: SCREENING CRITERIA The criteria for identifying future POPs will be crucial to determining the effectiveness of the treaty in regulating dangerous chemicals beyond the initially agreed dozen substances. Listed in Table 1, page 14 are the screening criteria which CEG2 has proposed that a substance must fulfil before it can progress to a more detailed evaluation as to whether it might warrant consideration for inclusion in the treaty. The numerical criteria are to be applied in a transparent, flexible, and integrated way. Therefore, the door will be left open for expert judgement to play an important role. Persistence in Water Agreement was not reached at CEG2 as to whether a value of 2 months or more vs. 6 months or more should be chosen as the screening criteria for persistence in water. Countries proposing the adoption of a 6 months or more value for persistence in water presented a bullet-point list of reasons to support that longer time period (reproduced in Box 1 below). Many other countries, including those of the EU, favored the adoption of a 2 month value and their reasons are also reproduced in Box 1. WWF supports the two month value for the reasons listed. 4 Box 1: Written arguments for water half-life values as submitted by experts at CEG2 “Preliminary arguments for a half-life in water of 6 months Water half-life data for existing POPs far exceeds 6 months. Data on soil and water half-life show that they are approximately the same (Boethling et al., Federle et al.). Sediment and water tests indicate that these half-lives in the two compartments are inexorably linked. Experimental data under laboratory conditions show that the half-life in water is longer than the half-life in soil (water-covered soil - Japanese data). The 2 month proposal is inherently based on a transport/dissipation argument – general definition of persistence relates to degradation not dissipation. Although the EU guidance document argues that sorption would make the substance unavailable for degradation and thus support different half-life criteria, recent experimental data indicate that sorbed substances can be degraded. Field data for ocean transport of POPs indicates that movement is much slower than in air (i.e., several order of magnitude) - AMAP and SETAC workshop. Risk Assessors consider a half-life of greater than 6 months to be persistent. Practical aspects Precaution should not be applied to selection of criteria values but rather in risk management phase. Consistent with global priorities - This is a Convention for those substances warranting international action because they cannot be controlled by local or regional action. 6 months will capture fewer substances; therefore there will be less need to prioritise chemicals for review or action ensuring greater possibility that global management will occur. 6 month half life will allow flexibility in application of the guideline based on data quality and representativeness.” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.15) The arguments in favor of the value of 2 months were submitted as follows: “Preliminary argument for a half-life in water of 2 months The half-life in water should be 2 months because of the following reasons: For many substances, the degradation in water and in soil and sediment is roughly similar, but for lipophilic substances, like POPs, which sorb to soil or sediment, and are less bioavailable, are likely to have longer half-lives in soil and sediment than in water. This has been already adopted in international regulatory evaluation procedures. Water is, in contrast to soil and sediment, a mobile transport medium like air. During transport in water, aquatic organisms are exposed to the POP. The velocity of transport in water is significantly slower than in air. A criteria value of 2 months for half-life in water seems to correspond well with the proposed half-life in air of 2 days.” 5 (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.15) 6 compound’s concentration in octanol to its concentration in water, the more fat soluble the compound and the more likely it is to bioconcentrate. Thus, the log Kow is used as an indication of a chemical’s potential for bioconcentration. The bioconcentration factor or BCF is based on laboratory studies and is defined as “the concentration of a substance in or adsorbed on an organism or specified tissues thereof divided by the concentration of the substance in the surrounding medium at steady state” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3). When the ratio is derived from accumulation through both the medium and the food chain, it is called the bioaccumulation factor (BAF) and this is generally based on field studies. The BAF is defined as “the concentration of a substance in an organism divided by the concentration of the substance in the surrounding medium” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3). In determining what weight to put on such data, BAFs are generally preferred to BCFs because BCFs are only evaluating partial bioaccumulation. the persistence in the receiving environment should be an important consideration, and this should be taken into account in determining screening values for half-lives. The CEG included a footnote to the effect that the conditions and methods of measurement of half-lives need to be defined. Nevertheless, because substances may persist longer than predicted in ecosystems in colder regions and may be bound to particles, it is argued that opting for the least restrictive value would be the best option. 5. Precaution should be applied to the selection of criteria values in order that suspected substances can be considered at greater depth at the risk profile stage. 6. If a 2 month value is adopted, more substances will potentially be captured. If several substances are deemed to possess the characteristics of a POP for possible inclusion under the treaty, then resource limitations will dictate that the most problematic ones will receive priority consideration. Bioaccumulation Potential Based on Log Kow It is much simpler to perform tests on substances to obtain log Kow values as compared to undertaking tests to obtain BCFs. The log Kow is thus a useful screening tool. However, at the risk profile stage, measured BCFs or BAFs must be provided because log Kow values are not always reliable indicators of the ability to bioconcentrate. The Kow or octanol-water partition coefficient is a way of measuring a substance’s propensity to bioconcentrate. It relies on dissolving the substance in a mixture of water and a solvent called octanol. The greater the ratio of the At CEG2, opinions were still divided as to whether a log Kow value of 4 or 5 should be used at the initial screening stage. The EU countries put forward detailed arguments in favor of adopting a log Kow value of 4 and WWF supports this WWF Recommendation No. 3: The criterion of a half-life in water of greater than 2 months should be chosen in preference to a half-life of greater than 6 months. 7 Because of the uncertain measurement and uncertain predictive value of log Kow and the fact that only actual bioaccumulation data or BCF studies will be relied upon in the final analysis, the lower proposed criterion of a log Kow of 4 or more should be accepted. The adoption of a log Kow screening criterion of 4 could also be an important indication of whether there is a political will to actually test some substances for their potential to bioconcentrate, and therefore how far the treaty will be of use in future to control substances which might be predicted to cause harm. To date, only a very small proportion of substances have been tested for their potential to bioconcentrate. Therefore, the more inclusive lower value should be adopted at the screening stage. The arguments put forward by national experts at CEG2 in support of each of the values under consideration are reproduced in Box 2. position. WWF Recommendation No. 4: For screening a log Kow value of 4 should be adopted in preference to a log Kow of 5. This recommendation is based on several reasons. First, it is well known that log Kow values are a poor tool to predict the bioaccumulation potential of substance, and therefore at the evaluation stage, a log Kow value will not be sufficient. Before a substance can be added to the treaty there must be a BCF study or BAFs which confirm the predicted potential for bioaccumulation. However, at the screening stage, it would certainly be unwise to dismiss substances with recorded log Kow values of less than 5 because a few substances with Kow values of considerably less than 5 appear to be extensively bioaccumulated. For example, some organotin compounds with log Kow values of around 3.3-3.6 have been found to have BCFs over 5000. Similarly, lindane has a log Kow in the range 3.2-3.7, and yet field measurements for bream in the River Elbe suggest a BCF of 10,00050,000 and a BCF of 26,198 was found in one study for the common mussel. Although the use of a log Kow of 5 might be seen to be a useful screen to indicate those substances which are likely to have a BCF over 5000, it can not be relied upon to pick out all such substances. There may also be substantial errors in some of the values put forward for log Kow. For example, chlordane has a BCF greater than 5000, yet in the Data Bank of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, a log Kow of 2.78 is quoted, which is significantly at odds with the value of 6.00 reported by other workers. With regard to data availability, it is interesting to note that even for chemicals traded in high volumes there is a great lack of actual measured data on their ability to bioconcentrate or bioaccumulate. The U.S. delegation presented details of the availability of test data for some 4620 chemicals of which 4103 were traded in high volumes. This showed that for 66% of these chemicals there were no available data on their BCFs or BAFs, and for 64% there were no log Kow values. Similarly, the German delegation found that even 25% of 2217 “new” substances (notified since 1981 and with a EU production level of more than .99 tonnes) did not have log Kow values. Interestingly, of the substances for which Kow values were available and for which there were data showing that they were not inherently biodegradable, 14 8 Box 2: Written arguments for log Kow values as submitted by experts at CEG2 “Preliminary arguments for a log Kow of 5 Japanese data indicate BCF > 5000 5000 Total Log Kow 4 to < 5 0 22 22 Log Kow 5 12 8 20 Consistent with all other POPs international treaties of a regional scale The existing POPs have log Kow > 5 The relationships between log Kow and BCF show that log Kow of 5 is equivalent to BCF of 5000 – logical connection. (Log Kow of 4 is equivalent to a BCF of approx. 500.) BCF must be greater than 5000, and log Kow greater than 5 for biomagnification to occur. Practical aspects Precaution should not be applied to selection of criteria values but rather in risk management phase. Consistent with global priorities - This is a Convention for those substances warranting international action because they cannot be controlled by local or regional action. Log Kow of 5 will capture fewer substances; therefore there will be less need to prioritize chemicals for review or action ensuring greater possibility that global management will occur. Log Kow of 5 allows for flexible application of guideline based on data quality and representativeness” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.15). The arguments put forward in support of a log Kow of 4 were as follows: “Preliminary arguments for a log Kow of 4 A log Kow value of 4 is needed only for the screening stage in cases when valid experimental BCF/BAF data are missing. It is not sufficient for the evaluation stage. Thus a log Kow of 4 is an incentive to generate lacking measured BCF/BAF data. At the screening stage it is important that the log Kow value is set sufficiently low so that its application will include all substances which bioaccumulate to an extent within the scope of the Convention and not to exclude potentially bioaccumulating substances. Bioaccumulation of substances in living organisms is dependent on the species and the environmental conditions; also, log Kow values may vary according to the methods of measurement. Even though generally accepted correlations between log Kow and BCF in fish have been established, it would be unwise to use the average correlation equations as a trigger. This may especially be the case when bioaccumulation concerns other aquatic species than fish. It should furthermore be recognized that there are even some already acknowledged POPs which are significantly more bioaccumulative in aquatic species than predicted by their log Kow values” (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.15). 9 had a log Kow greater than 4, and 7 had a log Kow greater than 5. However, data to determine whether these substances had a water half-life of 2 or 6 months were not available. This shows that many of the data which are essential for identifying POPs are just not available, even for the newer chemicals on the market. Therefore, there is a need for national and international regulatory regimes to address this data deficit. However, others felt that agreed text should not be re-discussed. Therefore, the final proposal from the CEG was to leave the heading in square brackets to allow for further debate at the INC. The currently proposed text for this section of Annex D is therefore: “(e) [Reasons for concern] [Adverse effects]: Evidence that toxicity or ecotoxicity data indicate the potential for damage to human health or the environment. This evidence [needs to] [should] [, where possible] include comparison of toxicity or ecotoxicity data with the detected or predicted levels of a substance resulting or anticipated from longrange environmental transport.” WWF Recommendation No. 5: Mandatory national and international testing programs should be instigated to determine the ability of substances to bioconcentrate and persist in the environment. Such testing programs should be tailored to determine whether substances meet the criteria necessary to be considered POPs under the treaty. To this end, organizations such as the International Standards Organization (ISO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) should be encouraged to develop and improve relevant test methods. There are three main issues here of concern. First, the extensive data which may be required could deter some countries from nominating a substance. Second, the wording may imply a high burden of proof. For example, it could be construed that in order for there to be potential for damage, actual or predicted levels in far away locations must exceed currently accepted lowest observable effect levels (LOELs) or no observable effect levels (NOELs). Third, if only toxicological and ecotoxicological effects are able to be considered, it could mean, for example, that if fish in a remote area were contaminated such that people no longer ate them, this would not be sufficient for this criteria to be met. Toxic Properties of the Substance At the first meeting of the CEG, delegates agreed that before a substance could be considered to meet the screening criteria, there should be some “reasons for concern” with regard to the toxicity of the substance. At CEG2, several experts proposed that the reasons for concern should relate to all the criteria, namely persistence, bioaccumulation, and potential for long range environmental transport, as well as the toxicity of the substance. They suggested that the heading for this paragraph should be “adverse effects.” With regard to the first issue, it needs to be recognized that making the data requirements too onerous might deter some countries, particularly developing countries, from nominating substances. 10 This would be a regrettable outcome, as global legislation should be able to achieve its aims and encourage participation from all nations. It could be argued that it would be very difficult for all countries to provide data comparing the current toxicity or ecotoxicity data with either modeling results predicting levels in far away places or with the detected levels found in far away locations. The information listed in paragraph (e), quoted above, must be submitted by a country proposing that a substance should be considered for inclusion in the treaty. More detailed evaluation will be needed at the evaluation stage. Therefore, any comparisons of toxicity data with actual or predicted levels in locations remote from the sources should not be mandatory. The colloquial meaning of the wording “where possible” should be retained, although this might be better phrased as, “countries wishing to provide comparison of toxicity or ecotoxicity data with the detected or predicted levels of a substance resulting or anticipated from long-range environmental transport are encouraged to do so.” However, regulatory action should not have to wait until a substance, by itself, is found in the environment at levels which might be predicted to cause harm. This approach is necessary because it is likely that many substances could act together to cause the threshold for effects to be exceeded. It is usually impossible to accurately predict the long-term effects on higher predators and man from a few shorter-term tests on a few selected species. Therefore, it is important that a precautionary approach is taken when evaluating the potential for toxicity. Consistent with this lower threshold, the Tolerable Daily Intakes of substances such as dioxins and PCBs have had to be revised downwards over time as new information on their effects has come to light. Global regulatory action should be able to be taken if the substance is believed to exert its effects via certain biochemical modes of action which give cause for concern, and that action should be taken even if the measured or predicted levels in the remote environment are below those known to cause harm at the present time. If the substance is biologically active, then at the screening stage, available toxicity data should only be used to prioritize the progression of substances to the more detailed evaluation stage. Recognizing that many countries are adamant that substantial concerns about toxicity must already be manifest, there is a need to clarify the burden of proof. WWF Recommendation No. 7: The substance should be able to meet the screening criteria if it is believed to exert effects via certain biochemical modes of action which give cause for concern. WWF Recommendation No. 6: At the screening stage, comparison of toxicity or ecotoxicity data with actual or predicted levels in far away locations should not be mandatory. With regard to the burden of proof, the wording might imply that the predicted environmental concentration (PEC) in the remote area must be compared to the predicted no effect concentration (PNEC), and be shown to be likely to exceed it, before it is accepted that there is evidence indicating potential for damage. 11 passes on to the review stage. The purpose of this is, Regulatory action should not have to wait until there are data showing that the substance has the potential to exceed, in the remote environment, the levels currently known to cause damage human health or the environment. “to evaluate whether the substance is likely to lead to significant adverse human health and/or environmental effects as a result of its long-range environmental transport, such that global action is warranted.” Another concern with regard to paragraph 1(e) relating to the toxicity of the substance is the narrowness of the reasons for concern. If only toxicological or ecotoxicological data can be considered, this would potentially exclude effects on fishing industries, unless it could be shown that the fish were actually likely to be damaged. For example, it could be envisaged that fish in a remote region might become contaminated such that people no longer wanted to eat them, which would have serious economic and social implications for indigenous people. However, the fish might not show signs of damage, and in fact their numbers may increase as people would no longer be eating them. Similarly, the people themselves would not be harmed because they no longer ate the fish, and the levels might be below those known to cause effects in humans. However, the effects of long-term exposure to low levels of pollutants may take many years to become apparent. Therefore, there is a need to ensure that the precautionary approach is taken when considering the likelihood of adverse effects. The precautionary approach (as laid down in Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration) states that, “where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.” The weight that is given to the precautionary approach will depend on where reference is made to it in the treaty. The U.S. delegation believes that it should only be in the preamble. However, in the preamble it will carry far less weight than if it was in the main body of the text, which is where some delegates, including those from most of the EU countries, feel it would be more appropriate. Norway would like the precautionary approach to be explicitly referred to in the criteria for identifying additional POPs. WWF Recommendation No. 8: At the screening stage, even in the absence of convincing toxicological data, a substance should be able to meet the criteria if adverse social or economic impacts have occurred due to concerns about the toxicity of the substance. PART IV: THE PRECAUTIONARY APPROACH WWF Recommendation No. 9: The precautionary approach should relate to all decisions taken as to whether or not If the substance is judged to have met the criteria of the initial screening stage then it 12 expertise with regard to those proposals. This would be in line with Principle 10 of the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development Rio Declaration, which states that “environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level,” and that “each individual shall have … the opportunity to participate in decisionmaking processes.” a proposed substance meets the screening criteria and the requirements for listing under the treaty, and the risk management objectives of the treaty. It should therefore be stated in the main body of the treaty text, in addition to being in the preamble. At the review stage, some testing of the substance (e.g. BCF) may be required, and hence there is a real need to ensure that such tests are undertaken in a timely fashion. Where tests are required, major producers should be contacted and informed of the situation in order to allow them to carry out the necessary testing, but if these are not undertaken within the time allotted, then the worst case should be assumed. The times allotted for various tests should be prescribed at the outset of the treaty by the Secretariat or a Technical Group. Such measures are needed if the treaty is to be seen as an effective tool for dealing with internationally suspect chemicals in a timely manner. WWF Recommendation No. 11: Governments should put in place mechanisms to enable members of the public and public interest/ environmental groups to make suggestions as to potential candidate substances for nomination. Assessing the Proposal and the Need for Full Transparency The Secretariat assesses whether the proposal contains all the data elements necessary for the Persistent Organic Pollutant Review Committee to evaluate whether the screening criteria have been met. In the event that the proposal is lacking certain necessary information, the Secretariat informs the Party or Parties proposing the substance. WWF concurs with the CEG that Parties and observers should be informed if the POP Review Committee considers that the screening criteria have not been met. There is also a need for transparency, so that the reasons for setting aside a proposal can be ascertained. WWF Recommendation No. 12: If a proposal to list a substance does not contain the information required at the screening stage, the Secretariat should inform all the Parties and WWF Recommendation No. 10: After an appropriate time period lack of data should be dealt with by using the worst case scenario. PART V: PROCEDURAL ISSUES Nomination of Substances as Potential Future POPs The CEG suggested that only a Party or Parties (that is countries which are a party to the treaty) would be able to propose a substance for screening and evaluation as to whether it should be considered for global action. However, there is a need to enable the public to contribute views and 13 evaluation stage because such considerations should not cloud sound scientific judgment as to whether a substance should be considered to be a POP requiring global action. However, there are extremely important socioeconomic considerations, and those must be thoroughly evaluated once a POP has met the evaluation criteria. Clearly socioeconomic considerations may dictate the need for time-limited derogations for the use of a particular POP in prescribed circumstances in certain areas. Even in those situations, though, for the longerterm WWF maintains that ultimate phase out is necessary due to the inherent characteristics of POPs. observers and indicate which data were missing in order that assistance can be provided in filling the data gaps. There is also a need for transparency in the evaluation of the risk profile. In the event that the POP Review Committee decides that a proposal shall not proceed, this document and a summary of the reasons why the proposal has been set aside should be available to the public. Similarly, the report to the Conference of the Parties (COP), which makes a recommendation as to whether or not the substance should be considered for listing based on the risk profile and the risk management evaluation, should be communicated to all Parties and observers and made available to the public. WWF Recommendation No. 14: Socioeconomic factors are important for determining appropriate time scales for the elimination of a POP, but should be given consideration only after the evaluation stage has determined that the substance is a candidate POP under the treaty. WWF Recommendation No. 13: At all stages in the process of establishing whether or not a proposed substance should be listed under the treaty, there should be full transparency of the decision making process. A summary of the reasons for the decisions taken, or recommendations made by the POP Review Committee, and all written documentation supporting such decisions or recommendations should be available to Parties, observers, and the public. When available, the report to the COP (making a recommendation as to whether or not the substance should be considered for listing under the treaty), should be communicated to all Parties and observers. Socio-economic Considerations WWF concurs with the output of CEG2 which suggests that socio-economic aspects should not play a role in the 14 TABLE 1: INITIAL SCREENING CRITERIA FOR A POTENTIAL POP (Taken from the final report of CEG2 (UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3) A future POP would be expected to meet at least one of the criterion laid down in each column. This table is therefore to be read downwards only. PERSISTENCE BIOACCUMULATION Half life in water is [>2 months] [>6 months] BCF or BAF in aquatic species >5000 ...or ...or Half-life in soils >6 months In the absence of BCF/BAF data log Kow > [4][5] ...or ...or Half-life in sediments >6 months Evidence that a substance presents other reasons for concern, such as high bioaccumulation in other species or high toxicity or ecotoxicity. ...or ...or Evidence that the substance is otherwise sufficiently persistent to be of concern within the scope of the Convention. Monitoring data in biota indicating that the bioaccumulation potential of the substance is sufficient to be of concern within the scope of the Convention. 15 POTENTIAL FOR LONG RANGE TRANSPORT TOXICITY CONCERNS Measured levels of potential concern in locations distant from the sources of release of the substance ...or [Reasons for concern] [Adverse effects] Evidence that toxicity or ecotoxicity data indicate the potential for damage to human health or the environment. This evidence [needs to][should][,where possible,] include comparison of toxicity and ecotoxicity data with the detected or predicted levels of a substance resulting or anticipated from long-range environmental transport. Monitoring data showing that long-range environmental transport of the substance, with the potential for transfer to a receiving environment, may have occurred via air or water or migratory species ... or Environmental fate properties and/or model results that demonstrate the potential for long range environmental transport, ... with the potential to transfer to a receiving environment in locations distant from the sources of release of the substance. For substances that migrate significantly through air, the air half-life should be > 2 days. TABLE 2: PERSISTENCE OF THE TWELVE POPS Taken from International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) paper 7/97 (revised 29 April 1998) Procedure for identifying further POP candidate substances for international action. Substance Half-life in air Half-life in water (temperate climate) Half-life in soil (temperate climate) Half-life in sediment (temperate climate) DDT 2 days > 1 year > 15 years no data Aldrin < 9.1 hours < 590 days approximately 5 years no data Dieldrin < 40.5 hours > 2 years > 2 years no data Endrin 1.45 hours > 112 days up to 12 years - Chlordane < 51.7 hours > 4 years approximately 1 year no data Heptachlor No data < 1 day 120-240 days no data HCB < 4.3 years > 100 years > 2.7 years Mirex No data > 10 hours > 600 years Toxaphene < 5 days 20 years 10 years - PCBs 3 - 21 days > 4.9 days > 40 days - Dioxins (2,3,7,8And 1,2,3,4-TCDD) around 9 days > 5 years 10 years > 1 year Furans (2,3,7,8-) 7 days > 15.5 days no data no data 16 > 600 years TABLE 3: LOG KOW VALUES AND BIOACCUMULATION DATA AND VAPOR PRESSURE OF THE 12 POPS Taken from International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) paper 7/97 (revised 29 April 1998) Procedure for identifying further POP candidate substances for international action. Substance Log Kow BCF (wet) Vapor pressure (Pa)4 DDT and metabolites 6.5 3,900 to 91,000 0.00002 Aldrin 5.1 - 7.4 10,710 0.01 Dieldrin 5.4 2,100-34,700 0.005 Endrin 5.2 4,200-49,800 0.003 Chlordane 6.0 7,100-37,800 0.0011 Heptachlor 4.3 - 5.3 1,100-20,000 0.01 HCB 5.9 7,800-22,000 0.0015 Mirex 7.1 18,100-20,400 0.0001 Toxaphene > 5.0 19,500-70,800 0.002 PCBs 6.9 57,000-800,000 0.2 to 0.00003 Dioxins (2,3,7,8-) 7.0 7,900-344,000 0.12 to 1.1E-10 (decreases with increasing chlorination Furans (2,3,7,8-) 5.82 2,570-66,000 0.00039-5.0E-10 (decreases with increasing chlorination) 17 United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Submission by the Delegation of Germany, POPs data availability study regarding new chemicals. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.3. 14 June 1999. SOURCES International POPs Elimination Network (IPEN). Background statement and POPs elimination platform. See www.worldwildlife.org/toxics and access POPs section. United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Submission by the Delegation of The United States of America. POPs data availability analysis (draft). UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.8. 14 June 1999. Persistent Organic Pollutants: Criteria and Procedures for Adding New Substances to the Global POPs Treaty, Technical Issue Brief, World Wildlife Fund, March 1999. UK Ministry of Defence Hydrographic Department. Ocean Passages for the World, 3rd edition, Taunton, Somerset, Ministry of Defence, 1973. United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Views expressed during discussions by the contact group on Annex D, Annex E, and Working Definitions. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.15. 18 June 1999 United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Comments submitted by Governments on the report of the Criteria Expert Group on the work of its first session. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/INF/3. 25 May 1999. For further information contact: World Wildlife Fund 1250 24th Street, NW Washington DC, 20037-USA Tel: 202/778-9625 Fax: 202/530-0743 Email: toxics@wwfus.org or www.worldwildlife.org/toxics United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Report of the second session of the Criteria Expert Group for persistent organic pollutants. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3. 18 June 1999. United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Submission by the Contact Group on Annex D, Annex E, and Working Definitions. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.14. 17 June 1999. UNEP Access their Web site at http://irptc.unep.ch/pops/ Report of the second session of the Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/3 United Nations Environment Programme Criteria Expert Group for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Second Session, Vienna, 14 - 18th June 1999, Submission by the Delegation of Denmark. Use of QSARs for the selection of persistent organic pollutants. UNEP/POPS/INC/CEG/2/CRP.4. 14 June 1999. ENB: Earth Negotiations Bulletins published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. Access their Web site at http://www.iisd.ca. Coverage of the second session of the POPs CEG can be found at http://www.iisd.ca/linkages/vol15/enb1512e.html. 18 Annex I WWF Recommendations for POPs INC Delegates On Criteria and Procedures for Adding New POPs to the Global POPs Treaty 1. Regional Scope of Coverage: Substances causing regional problems in several areas should be able to be covered under the treaty, even if there is no proof of environmental transport on a global scale. 2. Organo-metals: Organo-metal compounds should be able to be added to the treaty in future. 3. Half-life in Water: The criterion of a half-life in water of greater than 2 months should be chosen in preference to a half-life of greater than 6 months. 4. Log Kow of 4: For screening a log Kow value of 4 should be adopted in preference to a log Kow of 5. 5. Testing Programs: WWF Recommendation No. 5: Mandatory national and international testing programs should be instigated to determine the ability of substances to bioconcentrate and persist in the environment. Such testing programs should be tailored to determine whether substances meet the criteria necessary to be considered POPs under the treaty. To this end, organizations such as the International Standards Organization (ISO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) should be encouraged to develop and improve relevant test methods. 6. Toxicity Screening Criteria-Part I: At the screening stage, comparison of toxicity or ecotoxicity data with actual or predicted levels in far away locations should not be mandatory. 7. Toxicity Screening Criteria-Part II: The substance should be able to meet the screening criteria if it is believed to exert effects via certain biochemical modes of action which give cause for concern. Regulatory action should not have to wait until there are data showing that the substance has the potential to exceed, in the remote environment, the levels currently known to cause damage to human health or the environment. 8. Toxicity Screening Criteria-Part III: At the screening stage, even in the absence of convincing toxicological data, a substance should be able to meet the criteria if adverse social or economic impacts have occurred due to concerns about the toxicity of the substance. 9. Precautionary Approach: The precautionary approach should relate to all decisions taken as to whether or not a proposed substance meets the screening criteria and the requirements for listing under the treaty, and the risk management objectives of the treaty. It should therefore be stated in the main body of the treaty text, in addition to being in the preamble. 10. Lack of Data/Worst Case: After an appropriate time period lack of data should be dealt with by using the worst case scenario. 11. Non-party Suggestions on Substances: Governments should put in place mechanisms to enable members of the public and public interest/environmental groups to make suggestions as to potential candidate substances for nomination. 12. Missing Data: If a proposal to list a substance does not contain the information required at the screening stage, the Secretariat should inform all the Parties and observers and indicate which data were missing in order that assistance can be provided in filling the data gaps. 13. Transparency: At all stages in the process of establishing whether or not a proposed substance should be listed under the treaty, there should be full transparency of the decision making process. A summary of the reasons for the decisions taken, or recommendations made by the POP Review Committee, and all written documentation supporting such decisions or recommendations should be available to Parties, observers, and the public. When available, the report to the COP (making a recommendation as to whether or not the substance should be considered for listing under the treaty), should be communicated to all Parties and observers. 14. Socioeconomic Factors: Socioeconomic factors are important for determining appropriate time scales for the elimination of a POP, but should be given consideration only after the evaluation stage has determined that the substance is a candidate POP under the treaty. 20 Global Toxics Initiative The overall goal of the Global Toxics Initiative (GTI) is to end the production, release, and use of chemicals that are endocrine disruptors, bioaccumulative, or persistent within one generation – by no later than 2020. GTI consists of three interrelated components: Wildlife and Contaminants, Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), and Agriculture Pollution Prevention. While each three components have unique characteristics, they are all closely linked. Many POPs are endocrine disruptors and several pesticides are both endocrine disruptors and POPs. The main difference among the three components is in their approach to the global problem of toxic chemicals – The POPs program centers its work on policy development and advocacy, such as aiming for the phaseout and elimination of the most deadly, persistent pollutants like DDT, PCBs, and dioxins. The Wildlife and Contaminants program (WCP) focuses on the evolving science of endocrine disruptors and other toxic substances. The Agriculture Pollution Prevention (APP) program, in collaboration with farmers and growers, promotes integrated pest management (IPM) and other ecologically-sound alternatives to the use of pesticides. The Global Toxics Initiative is one of several initiatives that WWF has launched to address global threats to the Earth’s environment posed by unsustainable timber trade, overexploited fisheries, profligate used of toxic chemicals that harm wildlife, and unrestrained emissions of greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming. Addressing global threats is one of the three strategies pursued by WWF in its Living Planet Campaign— a call to action to make the close of this century and the opening of the next a turning point in the worldwide struggle to safeguard the critically endangered species, conserve endangered spaces—the world’s most important harbors of biological diversity that WWF calls the Global 200, and encourage changes in international policies and markets that contribute to environmental threats. To learn more about WWF’s Global Toxics Initiative, visit our Web site at: http://www.worldwildlife.org/toxics. World Wildlife Fund 1250 24th Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 www.worldwildife.org This publication was made possible through the generous support of the Jenifer Altman Foundation. Printed on recycled chlorine-free paper