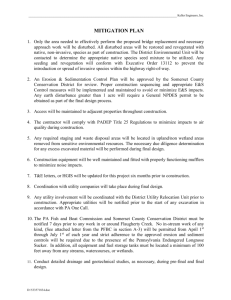

Common Legal Principles of Advanced Regulatory

advertisement