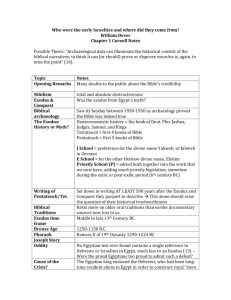

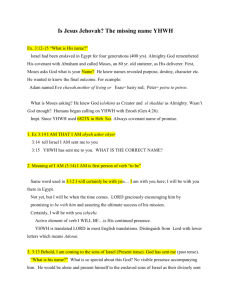

the_name - The Name Of God As Revealed In Exodus 3:14

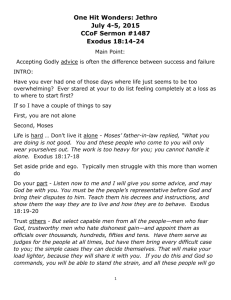

advertisement