2007 ECVIM Therapy of IBD(2)

advertisement

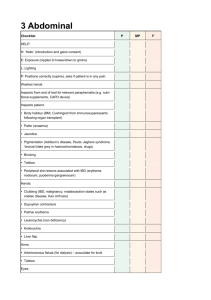

CURRENT AND EMERGING OPTIONS FOR IBD THERAPY Albert E. Jergens, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, ajergens@iastate.edu INTRODUCTION Arguably, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease is the most common histologic diagnosis in dogs and cats with histories of chronic vomiting and diarrhea. Uncontrolled studies and anecdotal reports from many clinicians and medical centers report a favorable response of IBD to several different forms of medical therapy. Unfortunately, the efficacy of these different forms of therapy has not been rigorously validated by randomized, controlled clinical trials.1 Evidencebased observations clearly imply a positive role for elimination dietary therapy of IBD alone or in combination with drug therapy; however, these data are limited. Non-traditional therapies including pre-/probiotic therapy for canine and feline IBD are in their infancy and have yet to be reported. Root causes for many of the deficiencies in our knowledge base of IBD therapy include poorly defined histopathologic criteria for IBD diagnosis and an absence of indices for defining clinical disease severity and the effect of therapy.2 This presentation will review current treatment strategies in human IBD, summarize drug/dietary therapies for canine and feline IBD, and review emerging therapies including the use of probiotics/prebiotics in experimental and companion animal IBD. MEDICAL THERAPY FOR HUMAN IBD The human inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis [UC] and Crohn’s disease [CD]) are complicated disease entities with a myriad of treatment options. Clinical studies must evaluate treatment strategies for UC versus CD; different stages of disease – induction vs. maintenance therapy and treatment of active vs. quiescent disease; single vs. multi-organ involvement; and disease flares. The treatment pyramid for UC includes 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA, most effective as a topical agent) and steroids as mainstays of therapy.3 For more severe disease, cyclosporine has become an accepted addition to the pharmacologic armamentarium.4 Immunosuppression with azathioprine (AZA) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) is quite effective in maintaining steroid-induced remission. There remains insufficient clinical evidence supporting the use of antibiotics or unique biologics (e.g., infliximab) in routine therapy of UC. Nutritional therapy for UC is indicated in patients with specific nutritional deficiencies or gross malnutrition. Considerably more clinical trial information is known concerning therapy for CD. Broadly, humans with mild-to-moderately active disease are treated in a step-wise fashion with oral mesalamine or sulfasalazine, adding antibiotics such as metronidazole or ciprofloxacin, then progressing to budesonide, and finally using oral corticosteroids in patients who fail to respond to initial first-line therapies.5 Budesonide is more useful with CD involving the ileum. AZA and 6-MP are indicated in steroid-dependent patients in an attempt to taper or withdraw steroids. Infliximab is used in patients with CD who do not achieve adequate clinical response despite treatment with conventional therapies. There is surprisingly little evidence for the use of elimination diets in CD as compared to their use in canine and feline IBD. Omega-3 fatty acids have been investigated in CD and UC with controversial results. Several studies have investigated probiotics (e.g., E. coli, Nissile, VSL#3) in human IBD where they have shown efficacy in the maintenance of UC and chronic pouchitis, respectively.6 PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY FOR CANINE AND FELINE IBD Management of IBD varies widely between clinicians. Well designed therapeutic trials have not been performed, and therapy remains largely empirical, being influenced by the rapidity of clinical remission, the severity of adverse effects, the acceptability by patients and clients, and drug costs. Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, prednisolone) are potent, rapidly acting oral or topical medications used as first-line therapy for canine and feline IBD. Budesonide is a poorly absorbed corticosteroid with limited bioavailability due to extensive first-pass metabolism (degraded by the liver) that may produce therapeutic benefit with reduced systemic toxicity. AZA and 6-MP are chemically-related immunomodulators. Their onset of full activity is slow and they may be associated with significant side effects (bone marrow toxicosis, hepatopathy) with chronic use. Oral cyclosporine inhibits T cell proliferation and has a rapid onset of action; however potential toxicity may limit its routine use. Salicylates, such as sulfasalazine, may be useful in cases of IBD colitis where the active moiety (5-ASA = mesalamine) provides topical anti-inflammatory actions. Antibiotics (metronidazole, tylosin) are widely prescribed for small and large intestinal IBD although there is little substantive clinical data supporting their use. Their mechanisms of action are unknown but may include modulation of resident microflora. Uncontrolled clinical trials attest to the fact that corticosteroids, used as a single agent or in combination with other medications, are effective in acute therapy of canine and feline IBD.1 One randomized controlled clinical trial of dogs having moderate-to-severe IBD showed that clinical remission rates, CIBDAI scores, and serum [CRP] were identical in dogs treated with prednisone alone versus dogs treated with a combination of prednisone and metronidazole.7 AZA/6-MP are predominantly used as a component of maintenance therapy to lower glucocorticoid doses. No data exists on controlled trials in the dog or cat. Oral cyclosporine @ 5mg/kg PO q 24 h has been reported in one small clinical trial to be useful in dogs with steroid-refractory IBD.8 Metronidazole has been reported to be effective as a single agent for mild feline IBD.9 Tylosin has been reported to be beneficial in dogs with chronic colitis.10 Enrofloxacin combined with other antimicrobials ameliorates clinical signs and histologic lesions in dogs with histiocytic ulcerative colitis.11 NUTRITIONAL THERAPY FOR CANINE AND FELINE IBD There is limited but good evidence-based data to support an important role for nutritional therapy in dogs and cats with IBD. Unfortunately, there are very few clinical trials where dietary treatments are compared to each other and to a control group (randomized, double-blind trials, etc). The use of moderately fermentable fiber supplements (psyllium, beet pulp) improves clinical signs in dogs and cats with IBD colitis. Potential mechanisms for these observations are numerous and may include binding of colonic irritants, normalization of dysmotility patterns, enhanced production of beneficial SCFA, and “prebiotic” restoration of normal microflora. Elimination dietary trials are beneficial in dogs and cats with chronic enteropathies (including IBD), and further serve to rule-out food-responsive causes for GIT signs. The optimal novel protein component and duration of feeding for control of clinical signs is debatable. Uncontrolled clinical trials attest to the fact that novel protein sources are beneficial in the treatment of canine/feline IBD. Additionally, these diets should be highly digestible, gluten-free, and nutritionally complete for long-term use.1 30% of cats with chronic GI signs were reported to have dietary sensitivity.12 Resolution or attenuation of clinical signs was observed in cats with lymphocyticplasmacytic colitis that were treated with fiber supplementation.13 In a separate study, 26/27 dogs having idiopathic colitis responded to a high fiber diet.14 PREBIOTICS AND PROBIOTICS IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE There is very little clinical data evaluating the use of probiotics to treat diarrheal disease in dogs or cats. Probiotic bacteria may reduce intestinal inflammation by diverse mechanisms including improved barrier function, modulation of the intestinal immune system, production of antimicrobials, and alteration of the intestinal microflora. Microencapsulated Enterococcus faecium SF68 strain is now commercially available as a dietary supplement (FortiFlora, Nestle Purina) for both dogs and cats. Clinical studies evaluating its use as a primary or adjunctive therapy for IBD have not been published to the author’s knowledge. Lastly, the addition of prebiotics such as fructooligosaccharides (FOS) for therapy of IBD has not been shown to be beneficial to date. The author is unaware of any dietary trials evaluating the effects of prebiotics in IBD. A probiotic cocktail was shown to reduce clinical severity (CIBDAI) and alter luminal floral numbers in a prospective, placebo-controlled trial in dogs with food-responsive diarrhea treated with an elimination diet.15 Using an ex vivo culture system derived from endoscopic biopsies, a probiotic cocktail was effective in reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine proteins and their expression in dogs with mild chronic enteropathy.16 Dietary FOS was shown to minimally impact beneficial fecal flora of healthy Beagles.17 Supplementation of the diet with FOS resulted in some alteration of the fecal flora of normal cats. Compared with samples from cats fed a basal diet, there was a trend for some beneficial bacteria to be increased after FOS supplementation although there was no change in total bacterial counts between diets.18 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS Although there is evidence-based data to support the use of elimination diets, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and some antibiotics in the treatment of dogs and cats with IBD, there are many aspects of therapy with these agents for which the data are lacking or inadequate. Additional prospective data are needed to resolve the areas of controversy. That said, further refinement in diagnosis of the “IBD syndrome” via improved histopathological criteria and use of robust clinical indices for assessment of disease activity will strengthen our understanding of how these therapies might provide optimal care to our patients. REFERENCES 1. Jergens AE. Vet Clin North Am: Small Anim Pract 1999; 29:501-521; 2. Jergens AE, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2003; 17:291-297; 3. Sutherland L, et al. Cochrane Database Systemic Rev 2005: issue 2; 4. Loftus CG, et al. Gut 2003; 52:172-173; 5. Sandborn WJ. Medical therapy for Crohn’s disease. In: Kirchner’s Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Sartor and Sanborn (eds), 2004 pp 531-554; 6. Ewaschuk JB, Dieleman LA. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12:5941-5950; 7. Jergens AE, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18:424; 8. Allenspach K, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20:239-244; 9. Jergens AE. Comp Cont Educ Pract Vet 1992; 14:509-518; 10. Westermarck E, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2005; 19:177-186; 11. Hostutler AR, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18:499-504; 12. Guilford WG, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2001; 15:7-13; 13. Dennis JS, et al. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993; 202:313-318; 14. Nelson RW, et al. J Vet Intern Med 1998; 2:133-137; 15. Sauter SN, et al. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2006; 90:269-277; 16. Sauter SN, et al. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2005; 29:605-622; 17. Willard MD, et al. Am J Vet Res 2000; 61:820825; 18. Sparkes AH, et al. Am J Vet Res 1998; 59:436-440.