A Chilly Classroom Climate?

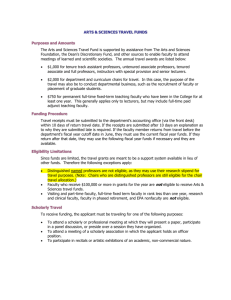

advertisement