An Empirical Investigation of Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand

advertisement

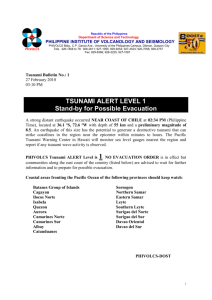

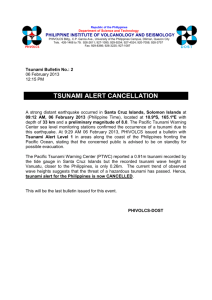

10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 The Impact of the December 2004 Tsunami: An Empirical Investigation of Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand Shamila A. Jayasuriya * *Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA. Contact information: phone: +1 740-593-2094, fax: +1 740-593-0181, email: jayasuri@ohio.edu. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 1 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 ABSTRACT This paper tests the hypothesis that the December 2004 tsunami has had a significant short term impact on the equity markets and trade behavior of the three worst affected economies of Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Using monthly data from February 1985 to July 2007, we estimate pooled cross-section and time-series regression models to examine direct and indirect effects of the tsunami. Our findings suggest that neither equity markets nor net exports are significantly different in the post- versus pre-tsunami time periods. However, results indicate that an appreciation of the U.S. dollar exchange rate in the post-tsunami period is significantly associated with increased stock market returns. Also, a real exchange rate appreciation is significantly correlated with lower net exports particularly in the post-tsunami era. JEL Classification: F14; G15 Keywords: Tsunami; Exchange rates; Net exports; Stock market returns; South Asian economies October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 2 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 INTRODUCTION The December 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami had a devastating impact on several Asian and African economies. In particular, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand were three of the worst affected countries that experienced extensive damage to human life, infrastructure and private property, and economic activity. The negative impact on economic activity was expected to be felt especially in sectors such as fisheries and tourism. However, as the January 2005 Bulletin of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka also points out, part of the negative impact was expected to be dampened by the reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts in the affected areas. There has been an outpouring of funds from foreign donors ranging from private individuals and organizations to national governments that has greatly facilitated the reconstruction and rehabilitation activities in the aftermath of the tsunami. In a September 2007 report by the United Nations’ Humanitarian Affairs division, the total funding received by affected countries is approximately 1.2 billion U.S. dollars and total humanitarian assistance received is approximately 6.2 billion U.S. dollars.1 Private donors consisting of individuals and organizations are the leading donors and Japan, U.K. and U.S. are among the six leading donor governments. This paper is based on the idea that the December 2004 tsunami had a significant short term impact on equity markets and trade behavior of Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. It is also partly based on the idea that the receipt of large foreign inflows in the post-tsunami period would have affected the domestic exchange rate with respect to foreign currencies in the aid recipient countries.2 In particular, the domestic currency is expected to have appreciated in value following the massive foreign capital inflows. Subsequently we investigate whether the tsunami has had a direct impact, and an indirect impact via the exchange rate on the aggregate equity October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 3 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 markets of the three countries. We also examine the impact on overall net exports and on the exports of a primary commodity for which data is available. Our empirical analysis uses monthly data for the time period from February 1985 to July 2007, which may vary based on data availability. We believe that a period of two and a half years from December 2004 to July 2007 reasonably captures the short term period immediately following the Tsunami. In the existing literature, an econometric investigation of the economic impacts of the tsunami has not yet been done for these three economies. Our study therefore takes steps in this direction with a focus on testing the hypothesis that the tsunami has had a significant effect on the equity markets and trade performance of Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Figure 1 motivates the analysis by plotting the U.S. dollar exchange rates for the 12 months before and after the month of December 2004. For Indonesia and Sri Lanka, we observe an appreciation of the exchange rate immediately after December 2004 whereas the exchange rate continues on a path of increasing value for Thailand. Based on estimation results that we will discuss later in the paper, our findings suggest that equity markets have not been directly affected by the tsunami. However, we do observe an indirect effect via the U.S. dollar exchange rate. Specifically, an appreciation of the U.S. dollar exchange rate in the post-tsunami period is associated with increased stock returns. In addition, overall net exports are not significantly different in the post- versus pre-tsunami periods. But there is clear evidence that an appreciation of the real exchange rate in the post-tsunami phase, regardless of whether the domestic prices are increasing relative to those in Japan, U.K., or the U.S., is linked with lower net exports. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we provide a brief review of the existing literature on the December 2004 tsunami. It will also contain a general October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 4 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 review of existing work on equity market returns and net exports in developed and emerging markets. Section 3 describes the estimation methodology and the data used in the analysis. Empirical results are provided in Section 4. And Section 5 concludes. LITERATURE REVIEW Athukorala and Resosudarmo (2005) provide a comprehensive analysis of the December 2004 tsunami with a focus on Indonesia and Sri Lanka. The nature and extent of the disaster are discussed first. The authors then provide an analytical discussion of the economic impact and the disaster management process immediately following the tsunami. A key focus is the international donor response and the limited aid absorptive capacity of affected countries. Nidhiprabha (2006) discusses the impact of three different shocks including the impact of the tsunami on the Thai economy. The author documents that the tsunami’s impact on the Thai tourism industry has not been as severe as initially expected. However, the long term negative impact on the environment has been underestimated. This includes the damages inflicted on the coastal ecosystems and the socioeconomic activities of local communities. Kurien (2005) discusses the devastating impact of the tsunami specifically on the fishing communities of Asia. The author raises several questions that deal with the safety and welfare of coastal fishing communities. A set of policy proposals that address the immediate rehabilitation of survivors and the future growth of fishing communities is also presented. Thorburn (2009) provides a qualitative study on how effective the livelihood recovery programs in Aceh, Indonesia have been since the 2004 tsunami. Based on survey results, the author finds that the degree and type of follow-up guidance and support that program beneficiaries received have been the main reasons for a successful livelihood recovery program in the Aceh communities. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 5 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Rajasingham-Senanayake (2005) analyzes the politics of representation that is set in the international development and reconstruction process following wars and natural disasters. With an application to Sri Lanka, the author emphasizes the importance of politically and culturally sensitive reconstruction policies without which renewed conflict and violence may be inevitable. On a similar note, Liddle (2005) also examines political interests and responses that emerge in the wake of natural disasters such as the tsunami and peace agreements in Aceh, Indonesia. Bandara and Naranpanawa (2007) use a computable generalized equilibrium (CGE) model to analyze the effects of the tsunami and reconstruction aid package on various macroeconomic variables and industry level output in Sri Lanka. Based on simulation results, the authors conclude that it is important to consider the combined effects of the tsunami and the reconstruction aid package. For example, despite the clear negative economic effects due to the tsunami there was evidence that the reconstruction package would in fact stimulate the economy. Using a quantitative approach, Lee et al (2007) examine whether the December 2004 tsunami affected the correlation structure in stock and foreign exchange markets for 26 countries. The authors first compute the conditional correlation coefficients that account for heteroskedasticity in market returns for both a stable and turmoil time period. They then compare the difference in correlations between the two periods and measure contagion as the significance of adjusted correlation coefficients for pair-wise countries. The authors find that the international stock markets did not suffer contagion. However, several foreign exchange markets experienced limited contagion effects up to three months after the tsunami. Our paper is also quantitative in nature and contributes to the existing work by providing an econometric investigation of the impact of the tsunami on two aspects of the economy, the equity markets and trade behavior, for the three most severely affected countries of the tsunami. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 6 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 In the existing literature, studies of aggregate stock market returns in both developed and emerging markets are abundant. Many models of equity returns are built primarily on autoregressive and moving average (ARMA) terms especially if the empirical analysis is based on high frequency data. Some, especially the emerging market studies, have included other potential determinants of stock return behavior such as foreign stock market returns, growth rates of domestic macroeconomic fundamentals, and variables that account for stock market liberalization and development policies to name a few. See Bekaert and Harvey (1997, 2000), De Jong and De Roon (2005), Henry (2000), and Jayasuriya (2005, 2006) for select studies. Evans and Speight (2006) study the impact of real time macroeconomic data on the U.K. stock returns and find that unexpected inflation and economic uncertainty are key determinants of U.K. stock returns over the business cycle. Also, Cauchie et al (2004) examine the developed stock market of Switzerland and find that both global and domestic economic conditions such as unexpected changes to industrial production and inflation in the G7 countries and the Swiss term structure influence stock market returns. Madsen (2006) finds a link between factor shares, in particular the labor share of income, supply shocks and technological innovations as important determinants of stock returns for a group of sixteen industrialized economies. There is an extensive literature on the determinants of bilateral trade between countries since the inception of the gravity model by Tinbergen (1962) modified later by others including Anderson and Van Wincoop (2003) in more recent years. While there is still debate on the theoretical appropriateness of the gravity model, it has been used widely and generated accurate results in empirical analyses over the years. See Deardorff (1998) for a good review of the existing works that provide a theoretical justification for the gravity model. In this paper, our focus is not on bilateral trade but on total trade of countries. Studies of overall trade typically October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 7 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 follow a partial equilibrium analysis based on the hypothesis of imperfect substitution between domestic and foreign goods. In this type of set up, the key determinants of export demand identified are relative prices and a measure of economic activity in the trading countries. See for example Arize (1990), Reinhart (1995), and Senhadji and Montenegro (1999). A good survey of related early empirical work is provided by Goldstein and Kahn (1985). Many studies have also investigated the role of exchange rate volatility on trade and found largely inconclusive evidence. See McKenzie (1999) and Choudhry (2005) for good discussions of the existing work. In recent years, the link between foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade has received much attention too and FDI has been increasingly incorporated into general equilibrium trade models such as those of Markusen and Venables (1998). The empirical literature on the role of FDI on trade is also inconclusive. In a comprehensive study, Sharma (2003) examines the link between FDI flows and export performance for India and is unable to detect a significant link between the two variables. METHODOLOGY AND DESCRIPTION OF DATA Methodology We use a pooled cross-section and time-series estimation methodology with White crosssection standard errors and covariances for all estimations. Fixed effects are used to account for country specific effects as appropriate. Equations (1) and (2) are estimated in order to analyze the equity market and trade behavior, respectively. Ri,t = i + Ri,,t-1 + ForeignStockReturnt + InterestRatei.t + InflationRatei,t + ExchangeRatei,t + TsunamiDummyt + InteractionDummyt + i,t October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 8 (1) 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 NXi,t = i + RERi,t + TsunamiDummyt + InteractionDummyt + DomesticStockPricei,t + ForeignStockPricei,t + Trendt + i,t (2) The dependent variable Ri,t in regression equation (1) is the real stock return for country i in month t. The intercept specification i allows for individual country effects that do not vary over time. Following previous work we add relevant ARMA terms to the model. We find that a parsimonious AR(1) term or, in other words, a one-month lagged stock return provides the best fit based on the Schwarz Information Criterion (BIC). Co-movements with foreign stock markets could largely explain the behavior of emerging market returns. The estimation therefore includes stock returns for Japan, U.K., and the U.S. which are three main developed markets of the world.3 The U.K. and U.S. equity market returns are somewhat highly correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.70 and we include only the one that better fits the model. Growth rates of domestic macroeconomic fundamentals such as the interest rate, inflation rate, and exchange rate are also considered because they may be good indicators of prevailing economic conditions. We look at three different exchange rates in the analysis, which are the national currency per U.S. dollar, U.K. pound, and the Japanese yen. The rationale here is that Japan, U.K. and the U.S. are three leading donors in the reconstruction and rehabilitation process following the tsunami and there is reasonable expectation that large inflows of these currencies may have affected the value of the domestic currency of aid recipient countries. The levels and growth rates of the three exchange rates are highly correlated with the correlation coefficient estimates ranging anywhere from 0.85 to 0.99. As a result, separate regressions are estimated for each exchange rate. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 9 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 A dummy variable that accounts for the tsunami is also included in the estimation. This variable is constructed by setting equal to 0 the months preceding the tsunami and setting equal to 1 all remaining months starting from December 2004. A significant negative coefficient on the dummy variable would suggest that equity market returns were considerably lower in the post tsunami era. We also create an interaction variable of the tsunami dummy and the relevant exchange rate variables. By construction, we obtain three interaction variables based on the three different exchange rates. The interaction variables as constructed are able to capture the effect of exchange rate changes on equity market returns specifically in the post tsunami period. This would allow us to investigate whether equity markets have been especially sensitive to exchange rate changes in the post tsunami time period. We then repeat regression estimation (1) by replacing the exchange rate variable with the real exchange rate (RER), which is defined as the ratio of foreign to domestic prices measured in the same currency. A decrease in RER therefore indicates an appreciation of the real exchange rate. A decreasing real exchange rate lowers the external competitiveness of the economy via the trade balance and has a negative impact on aggregate income. To that extent, a real exchange rate appreciation may be reflected in lower equity returns. The use of three exchange rates in the model necessitates the computation of three different real exchange rates and a new set of interaction variables as well. The levels and growth rates of the real exchange rates are also highly correlated with the correlation coefficients ranging from 0.81 to 0.99. Therefore, as was done earlier, separate regressions will be estimated for each real exchange rate. The dependent variable NXi,t in regression equation (2) is the overall net exports in millions of U.S. dollars for country i in month t. Here, too, the intercept specification i allows for individual country effects that do not vary over time. Following previous work, we add the October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 10 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 real exchange rate as a key determinant of net exports. A real exchange rate appreciation is expected to have a negative impact on net exports because it would make exports more expensive and imports less expensive, which will lead to a decrease in the trade balance. In this estimation, too, we add the tsunami dummy variable to examine net exports in the post- relative to the pre-tsunami era. A significant negative coefficient estimate would suggest a decline in net exports following the tsunami. As before, the interaction variables would capture the effect of real exchange rate changes on net exports particularly in the post-tsunami time period.4 Several proxy variables for economic activity are also added to the estimation model. In the absence of a monthly measure of production, the aggregate stock price index of an economy may in fact be a good proxy. For example, the aggregate stock price indexes for Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand are used as approximate measures of domestic economic activity. A well performing stock price index can be a reasonable indicator of good economic conditions. Better economic conditions would also mean a higher demand for imports and, therefore, a negative impact on net exports. The aggregate stock price indexes for the U.S., U.K. and Japan are also used to proxy the economic conditions of the trading partners.5 The conjecture here is that better performing stock prices in the foreign countries would imply better economic conditions abroad that would in turn lead to a higher demand for exports. The aggregate stock price indexes for the U.S. and U.K. are highly correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.98 and we, therefore, use only one of the two that provides the better fit for our estimations. We also add a time trend to our estimation equation (2). A visual inspection of the net exports data series raised the potential issue of non-stationary data. As a result, we conducted the Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) test to formally detect a unit root in the series. The hypothesis of a unit root is rejected at the one percent critical level when a time trend is included October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 11 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics in the alternative hypothesis of the test. ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Adding a time trend to the estimation therefore eliminates a potential spurious regression problem in our model.6 Lastly, we repeat regression estimation (2) by replacing net exports with the exports of a primary commodity measured in millions of U.S. dollars for which monthly data is available. Overall net exports may not effectively isolate the impact of the tsunami on the sectors that were affected the most. For example, the fisheries and tourism sectors are undoubtedly two key sectors that were affected the most. And we can reasonably expect the export earnings related to these two industries to have decreased dramatically following the tsunami even if there was no apparent decline in overall net export earnings.7 In the absence of data for such sectors, we can still raise an interesting question. That is, could the export earnings of a primary commodity have been affected especially via real exchange rate changes? Primary commodities have traditionally played a major role in the export performance of emerging market economies and, therefore, of growth and development prospects. Here, we consider petroleum exports for Indonesia, tea exports for Sri Lanka, and rice exports for Thailand. In the early 1980s the export earnings of these three commodities were about 60, 35, and 20 percent of total export earnings respectively but have decreased to about 10 percent or even less in the most recent years. 8 The Europa World Yearbook 2005-2006 indicates that machinery and transport equipment are in fact among the principal exports for Indonesia in 2003. Data also indicates that textiles and garments are the main commodity exports for Sri Lanka in 2005, which made up approximately 43.30 percent of total export earnings. On the other hand, machinery was the primary export for Thailand in the year 2005 making up about 44.70 percent of total export earnings. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 12 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Description of the data and preliminary statistics All estimations are based on monthly data from February 1985 to July 2007, which may vary based on data availability.9 The equity prices are obtained from the Datastream database for all the markets.10 All returns are measured as the log difference of equity prices denominated in the local currency. All returns are deflated by the relevant Consumer Price Index (CPI) in order to obtain real returns. The CPI data is from the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) International Financial Statistics (IFS) database. Data for macroeconomic fundamentals such as the domestic interest rate, inflation rate, nominal and real exchange rates are also from the IFS database.11 The net exports and primary commodity exports data in millions of U.S. dollars are from the IFS database as well. As discussed earlier, the motivation of our paper stems partly from the idea that foreign aid flows after the tsunami are expected to have appreciated the domestic currency with respect to the relevant foreign currencies. Table 1 presents some informal evidence to this regard especially for Sri Lanka and Thailand. In particular, Table 1 documents the national to the foreign, which is the U.S., U.K., and Japanese, currency exchange rates for Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand for selected months before and after the tsunami. For both Sri Lanka and Thailand, all three exchange rates indicate a relative increase in value of the domestic currency for at least 12 months following the December 2004 tsunami. This, however, is not the case for Indonesia. We observe that the Indonesian Rupiah to the U.K. pound exchange rate appreciated in value during the one month immediately following the tsunami relative to the one month preceding it. All other cases indicate a depreciation of the Indonesian currency relative to the foreign currencies. We are nevertheless able to test the hypotheses that changes to the nominal and real October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 13 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 exchange rates, despite an appreciation or depreciation, have had a significant impact on equity markets and trade behavior for the three economies in the post tsunami time period. EMPIRICAL RESULTS Table 2 presents the results for the impact of the tsunami on real stock returns. 12 We observe that real returns are not significantly different in the post- versus the pre-tsunami period. We observe however that an appreciation (depreciation) of the U.S. dollar exchange rate is associated with increased (decreased) real returns in the post-tsunami era. That is, equity market behavior appears to be sensitive to the U.S. dollar exchange rate in the aftermath of the disaster such that an increase in the value of the domestic currency relative to the U.S. dollar is linked with a positive response of the equity markets. Interestingly, the exchange rate does not appear to have a significant effect on equity returns unless the tsunami is accounted for. The domestic interest rates, on the other hand, indicate a significant negative impact on equity returns. That is, higher interest rates are associated with lower equity returns, which is a phenomenon that is also observed in the U.S. stock markets. For example, an interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve Board often triggers a decrease in stock prices because of the contractionary economic conditions a higher interest rate typically entails. In addition, the lagged stock returns and foreign stock returns also appear to be significant determinants of equity market behavior in general. In particular, the domestic equity markets react positively to better past performance of their own as well as better concurrent performance of major developed markets of the world. Table 3 presents results for the impact of the tsunami on real stock returns while replacing the nominal with the real exchange rate in the estimation model. As before, results do not indicate an apparent distinction in equity returns in the post- relative to pre-tsunami periods. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 14 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 We also observe that changes to the real exchange rate do not significantly affect equity returns in the post-tsunami time period or otherwise. The interest rate however is still a significant determinant as are the lagged stock returns and foreign stock market movements. A possible interpretation of our results is that a strengthening of the domestic currency against the U.S. dollar is observed immediately in the currency markets and perceived as positive to the economy perhaps due to the implications on short term capital inflows. The impact of a real exchange rate appreciation on the economy via the trade balance however is of a longer term nature and is not felt immediately in the equity markets. Table 4 documents the impact of the tsunami on net exports.13 Clearly, net exports are not significantly different in the post- versus pre-tsunami time periods. The interaction variable suggests however that a real exchange rate appreciation (depreciation) in the post-tsunami period is significantly associated with lower (higher) net exports. The impact of the real exchange rate on net exports is visible even if the tsunami is not accounted for but, interestingly, the magnitude of the real exchange rate effect is greater following the tsunami. That is, net exports have become more sensitive to real exchange rate changes after the disaster. Also, the domestic stock prices have a significant negative impact on net exports. To the extent that increasing domestic stock prices imply improving economic conditions, there would be a higher demand for imports leading to a decrease in net exports. On the other hand, increasing stock prices in foreign equity markets may reflect better economic conditions of trading partners that would lead to a higher demand for domestically produced goods and, therefore, increased exports. For the most part, we do observe a significant positive link between foreign stock prices and net exports. Although, the significant negative link observed between the Japanese Nikkei index and net exports is contrary to what we expect. A possible explanation is that the import demand for October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 15 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 some goods originating in Japan is now being met by exports from emerging markets other than Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand as the Japanese economy continues to become wealthier. This could be due to changes in consumer tastes and preferences and possibly due to new developments in trade agreements. Lastly, Table 5 shows the impact of the tsunami on the exports of a primary commodity. In general, primary commodity exports are lower in the post- versus the pre-tsunami time period. Given that the production capacities of petroleum, tea, and rice in the respective countries were not substantially affected by the tsunami, it is difficult to attribute the decline in these exports to the tsunami alone. An alternative explanation is that there have been structural changes to the composition of exports of these countries with primary commodities decreasing as a percentage share of total exports over time. And such structural changes may have coincided with the time around the December 2004 tsunami. Data from the International Trade Statistics database show that fuel exports were the leading merchandise exports for Indonesia in the mid 1980s. However, manufactures especially machinery and transport equipment have been the main exports for Indonesia in the recent years. For Sri Lanka, agricultural products were the primary merchandise exports in the mid 1980s whereas manufactures especially clothing have been the key exports in the last few years. For Thailand, too, agricultural products were the leading merchandise exports in the mid 1980s but these have been replaced by manufactured items including machinery/transport equipment and office/telecommunications equipment in the recent years. The interaction variable suggests that primary commodity exports are sensitive to real exchange rate changes in the post-tsunami period. In particular, a real exchange rate appreciation (depreciation) is associated with decreased (increased) exports. Unless the tsunami October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 16 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 is specifically accounted for, a real exchange rate depreciation is in fact associated with decreased primary commodity exports. It is very likely that we are observing a crowding-out effect in which a real exchange rate depreciation benefits exports other than primary commodities. For example, manufacture exports such as machinery/transport equipment and textiles/garments have gained momentum for these countries in recent years and, as a result, the export demand for primary commodities may continue to decline even in the midst of a relative fall in domestic prices. The negative coefficient estimates on the domestic and some of the foreign stock prices provide further evidence that the commodity exports considered here are no longer the primary exports as they may have been in the past. The Japanese stock prices are however mostly consistent with our expectations. Therefore, better economic conditions in Japan appear to be linked with higher primary commodity exports from the three countries. CONCLUSION In this paper, we examined the impact of the December 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami on the three most severely affected economies of Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Specifically, we investigated the research hypothesis that the tsunami has had a significant short term impact on the equity market and trade behavior of the three Asian economies. Using monthly data from February 1985 to July 2007 in a pooled cross-section and time-series analysis, we found that equity market returns and net exports are not significantly different in the postversus pre-tsunami time periods. However, we did observe an indirect effect via exchange rates. In particular, an appreciation of the U.S. dollar nominal exchange rate in the post-tsunami period is associated with increased stock returns. Also, an appreciation of the real exchange rate is associated with lower net exports especially in the post-tsunami era. In addition, we found October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 17 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 evidence that primary commodity exports are lower in the aftermath of the tsunami, which is a result that we have argued may not be attributed to the devastating impacts of the tsunami alone. Therefore, even though a direct impact of the tsunami was not felt on the equity markets or net exports, we did observe an indirect effect via exchange rate changes. Provided that sufficient data is available, an investigation of the fisheries and tourism sectors is likely to reveal a direct negative impact of the tsunami on the production capacities of these sectors. The indirect effects on overall net exports that we observed in the post-tsunami period could very well reflect a drop in export earnings in the fisheries and tourism industries on the one hand and an increase in import expenditures for emergency relief goods needed for reconstruction and rebuilding efforts on the other hand. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 18 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 References Anderson, J. E. and Van Wincoop, E. (2003). Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review, 93(1), 170-192. Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions 2005-2006, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Arize, A. C. (1990). An econometric investigation of export behavior in seven Asian developing countries. Applied Economics, 22(7), 891-904. Athukorala, P. and Resosudarmo, B. P. (2005). The Indian Ocean tsunami: Economic impact, disaster management and lessons. Asian Economic Papers, 4(1), 1-39. Bandara, J. S. and Naranpanawa, A. (2007). The economic effects of the Asian tsunami on the ‘tear drop in the Indian Ocean’: A general equilibrium analysis. South Asia Economic Journal, 8(1), 65-85. Bekaert, G. and Harvey, C. R. (1997). Emerging equity market volatility. Journal of Financial Economics, 43(1), 29-77. Bekaert, G. and Harvey, C. R. (2000). Foreign speculators and emerging equity markets. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 565-613. Cauchie, S., Hoesli, M., and Isakov, D. (2004). The determinants of stock returns in a small open economy. International Review of Economics and Finance, 13(2), 167-185. Choudhry, T. (2005). Exchange rate volatility and the United States exports: Evidence from Canada and Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 19(1), 51-71. De Jong, F. and De Roon, F. A. (2005). Time-varying market integration and expected returns in emerging markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 78(3), 583-613. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 19 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Deardorff, A. V. (1998). Determinants of bilateral trade: Does gravity work in a neoclassical world? In J. A. Frankel (Ed.), The Regionalization of the World Economy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Evans, K. P. and Speight, A. E. H. (2006). Real-time risk pricing over the business cycle: Some evidence for the UK. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33(1-2), 263-283. Goldstein, M. and Kahn, M. S. (1985). Income and price effects in foreign trade. In R. W. Jones and P. B. Kenen (Eds.), Handbook of International Economics 2. Amsterdam: North-Holland. Henry, P. B. (2000). Stock market liberalization, economic reforms, and emerging market equity prices. Journal of Finance, 55(2), 529-564. Jayasuriya, S. A. (2005). Stock market liberalization and volatility in the presence of favorable market characteristics and institutions. Emerging Markets Review, 6(2), 170-191. Jayasuriya, S., A. (2006). A closer look at frontier markets. Journal of Emerging Markets, 11(2), 50-58. Kurien, J. (2005). Tsunamis and a secure future for fishing communities. Ecological Economics, 55(1), 1-4. Lee, H.-Y., Wu, H.-C., and Wang, Y.-J. (2007). Contagion effect in financial markets after the south-east Asia tsunami. Research in International Business and Finance, 21(2), 281-296. Liddle, R. W. (2005). Year one of the Yudhoyono-Kalla Duumvirate. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 41(3), 325-340. Madsen, J. B. (2006). The dynamic interaction between equity prices and supply shocks. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 45(3-4), 3-30. Markusen, J. and Venables, J. (1998). Multinational firms and the new trade theory. Journal of International Economics, 46(2), 183-203. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 20 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 McKenzie, M. D. (1999). The impact of exchange rate volatility on international trade flows. Journal of Economic Surveys, 13(1), 71-106. Nidhiprabha, B. (2006). The buffeting of Thailand by the unholy trinity of avian influenza, tsunami, and the oil price shock. Asian Economic Papers, 5(2), 117-129. Rajasingham-Senanayake, D. (2005). Sri Lanka and the violence of reconstruction. Development, 48(3), 111-120. Reinhart, C. M. (1995). Devaluation, relative prices, and international trade: Evidence from developing countries. IMF Staff Papers, 42(2), 290-312. Senhadji, A. S. and Montenegro, C. E. (1999). Time series analysis of export demand equations: A cross-country analysis. IMF Staff Papers, 46(3), 259-273. Sharma, K. (2003). Factors determining India’s export performance. Journal of Asian Economics, 14(3), 435-446. The Europa World Yearbook 2006, Vol. I (A-J), 47th edition, London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. The Europa World Yearbook 2006, Vol. II (K-Z), 48th edition, London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Thorburn, C. (2009). Livelihood recovery in the wake of the tsunami in Aceh. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 45(1), 85-105. Tinbergen, J. (1962). Shaping the World Economy. New York, NY: The Twentieth Century Fund. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 21 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Table 1: Exchange rates (national per foreign currency) for selected months before and after the tsunami Month 1-mo 2-mo 3-mo 4-mo 5-mo 6-mo 12-mo 18-mo 24-mo National Currency to the US Dollar Indonesia pre post 9179.80 9109.33 9104.15 9117.28 9147.10 9130.25 8963.14 8796.13 8736.92 National currency to the UK Pound Indonesia pre post 9240.67 9229.05 9255.55 9307.60 9355.49 9381.34 9686.13 9562.81 9468.59 17630.46 17176.76 16924.42 16799.65 16806.67 16780.46 16407.04 15696.97 15218.93 pre post pre post pre post 104.84 104.68 104.36 104.06 103.89 103.76 101.21 99.42 98.79 100.80 99.99 99.76 99.67 99.67 99.67 100.22 100.87 101.52 201.28 197.32 193.94 191.70 190.88 190.71 185.29 177.46 172.12 190.72 188.47 188.99 188.56 188.70 187.67 183.49 182.23 185.01 1.01 1.00 0.98 0.97 0.96 0.96 0.93 0.91 0.89 0.97 0.96 0.96 0.95 0.95 0.95 0.92 0.91 0.90 pre post pre post pre post 39.30 39.89 40.36 40.62 40.79 40.83 40.32 40.22 40.72 38.88 38.68 38.57 38.72 38.87 39.09 40.11 39.85 39.33 75.48 75.18 74.96 74.77 74.89 75.00 74.85 72.39 71.29 73.66 72.96 73.11 73.29 73.63 73.62 73.39 71.99 71.64 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.37 0.37 0.37 0.38 0.37 0.37 0.37 0.37 0.37 0.37 0.36 0.35 Sri Lanka 1-mo 2-mo 3-mo 4-mo 5-mo 6-mo 12-mo 18-mo 24-mo 8952.15 8898.46 8892.95 8878.16 8903.51 8891.62 8883.76 8580.26 8419.84 Sri Lanka Thailand Thailand Source: Datastream database. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 8830.66 8703.84 8581.02 8515.99 8494.89 8450.46 8269.44 8057.54 7847.69 Sri Lanka Thailand 1-mo 2-mo 3-mo 4-mo 5-mo 6-mo 12-mo 18-mo 24-mo 17500.97 17396.29 17535.87 17605.66 17713.00 17658.66 17713.65 17278.10 17249.90 National currency to the Japanese Yen Indonesia pre post 22 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Table 2: The impact of the tsunami (direct, and indirect via the nominal exchange rate) on real stock returns Variables (1) National currency per US dollar exchange rate (2) National currency per UK pound exchange rate (3) National currency per Japanese Yen exchange rate 0.1703*** (0.0436) 0.0984 (0.0616) 0.1393*** (0.0554) 0.2716** (0.1290) 0.3322*** (0.1228) Lagged Stock Returns Stock Returns_US Stock Returns_UK 0.3573*** (0.0719) Stock Returns_Japan 0.1341* (0.0699) 0.2597** (0.1111) 0.1548 (0.1076) Interest Rate -0.0448*** (0.0170) -0.0723*** (0.0274) -0.0552** (0.0217) Inflation Rate -0.0001 (0.0006) 0.0001 (0.0007) 0.0002 (0.0008) Exchange Rate -0.1717 (0.1652) -0.1844 (0.1513) -0.0949 (0.1173) Tsunami Dummy Variable -0.0025 (0.0072) 0.0063 (0.0086) 0.0051 (0.0082) Interaction Dummy Variable -0.9344** (0.4322) 0.1133 (0.2472) -0.1727 (0.2360) R-squared Log Likelihood Observations 0.1145 803.3260 761 0.1419 436.7270 405 0.0954 506.5028 490 Note: White-cross section standard errors are given in parentheses. Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels are indicated by ***, **, and * respectively. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 23 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Table 3: The impact of the tsunami (direct, and indirect via the real exchange rate) on real stock returns Variables (4) National currency per US dollar exchange rate (5) National currency per UK pound exchange rate (6) National currency per Japanese Yen exchange rate 0.1758*** (0.0443) 0.1364*** (0.0510) 0.1443** (0.0564) 0.3751*** (0.1194) 0.3254*** (0.1228) Lagged Stock Returns Stock Returns_US Stock Returns_UK 0.3554*** (0.0723) Stock Returns_Japan 0.1425** (0.0704) 0.1339 (0.0947) 0.1626 (0.1072) Interest Rate -0.0455*** (0.0170) -0.0500*** (0.0184) -0.0554** (0.0217) Inflation Rate -0.0003 (0.0006) 0.0001 (0.0008) 0.0001 (0.0008) Real Exchange Rate -0.1324 (0.1501) -0.1433 (0.1249) -0.0629 (0.1049) Tsunami Dummy Variable -0.0005 (0.0082) 0.0064 (0.0083) 0.0076 (0.0083) Interaction Dummy Variable 0.0605 (0.4026) 0.2943 (0.2110) 0.0815 (0.2082) R-squared Log Likelihood Observations 0.1070 800.1052 761 0.1032 567.9568 542 0.0914 505.4263 490 Note: White-cross section standard errors are given in parentheses. Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels are indicated by ***, **, and * respectively. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 24 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Table 4: The impact of the tsunami (direct, and indirect via the real exchange rate) on net exports (7) National currency per US dollar exchange rate (8) National currency per UK pound exchange rate (9) National currency per Japanese Yen exchange rate 0.0950*** (0.0189) 0.0384*** (0.0139) 0.0343 (0.0284) 50.6549 (123.3941) -137.4104 (144.4793) -87.9421 (153.6488) Interaction Dummy Variable 0.1091*** (0.0192) 0.0432*** (0.0109) 0.1036*** (0.0288) Domestic Stock Prices -0.5774*** (0.0620) -0.5740*** (0.0639) -0.5598*** (0.0872) Foreign Stock Prices_US 0.5080*** (0.0993) 0.3329*** (0.0971) 0.3683*** (0.1027) Foreing Stock Prices_Japan -0.0056*** (0.0020) 0.0172** (0.0077) 0.0133 (0.0085) 1.0514* (0.5867) 4.5909*** (1.0851) 3.9004*** (1.2789) 0.7000 -5972.0390 798 0.7093 -4316.0740 569 0.6604 -3923.0000 514 Variable Real Exchange Rate Tsunami Dummy Variable Trend R-squared Log Likelihood Observations Note: White-cross section standard errors are given in parentheses. Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels are indicated by ***, **, and * respectively. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 25 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Table 5: The impact of the tsunami (direct, and indirect via the real exchange rate) on primary commodity exports (10) National currency per US dollar exchange rate (11) National currency per UK pound exchange rate (12) National currency per Japanese Yen exchange rate -0.0130*** (0.0032) -0.0102*** (0.0016) -0.0267*** (0.0044) Tsunami Dummy Variable -2.0258 (8.3283) -24.3551** (9.4741) -16.7627* (9.1784) Interaction Dummy Variable 0.0310*** (0.0068) 0.0170*** (0.0038) 0.0337*** (0.0086) Domestic Stock Prices -0.0063 (0.0044) -0.0115*** (0.0041) -0.0083* (0.0044) -0.0720*** (0.0138) -0.0624*** (0.0134) Variable Real Exchange Rate Foreign Stock Prices_US Foreign Stock Prices_UK -0.0074** (0.0031) Foreign Stock Prices_Japan -0.0014** (0.0006) 0.0040*** (0.0006) 0.0038*** (0.0007) Trend 0.5030*** (0.1047) 1.1447*** (0.1405) 0.9943*** (0.1415) 0.8912 -4315.3570 759 0.9359 -2857.9550 533 0.9395 -2569.6530 478 R-squared Log Likelihood Observations Note: White-cross section standard errors are given in parentheses. Significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels are indicated by ***, **, and * respectively. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 26 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Figure 1: Exchange rates (national currency to the US dollar) for 12 months around the tsunami Indonesia 10400 10000 9600 9200 8800 8400 8000 2004M01 2004M07 2005M01 2005M07 Sri Lanka 105 104 103 102 101 100 99 98 97 96 2004M01 2004M07 2005M01 2005M07 Thailand 42 41 40 39 38 2004M01 2004M07 2005M01 2005M07 Note: The solid line in all three graphs indicates the month of December 2004 when the Indian Ocean tsunami occurred. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 27 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 Endnotes 1 The relevant data are available at http://www.reliefweb.int/fts (Table ref: R5 and Table ref: R24). 2 The 2005 and 2006 Annual Reports on the Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) indicate that all three countries had at the time of the December 2004 tsunami an exchange rate system where exchange rates are determined by supply and demand conditions in the foreign exchange markets. The exact classifications are managed floating with no pre-determined path for the exchange rate for both Indonesia and Thailand, and an independently floating exchange rate for Sri Lanka. 3 The choice of Japan, U.K., and the U.S. is appropriate also because they are among the leading donors of tsunami relief to the affected countries. 4 Here, too, separate regressions will be estimated for the different real exchange rates and their respective interaction variables. 5 The International Trade Statistics database made available at www.wto.org documents that the U.S. and Japan are among the top three destinations for merchandise exports for Indonesia and Thailand. For Sri Lanka, the main destination for its merchandise exports is the U.S. with the European Union and India ranking second and third, respectively. 6 Some measure of trade policy would also be a good choice of an explanatory variable to the model. Because of the lack of data, however, we are not able to account for the impact of trade restrictions on net exports. Data for import tariffs made available by the International Trade Statistics database provide an indication of the extent of trade restrictions in the three countries. For example, the simple average ad-valorem duties applied on all goods in the year 2007 were 6.9, 11.2, and 10.5 percent for Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand respectively. Also, exports to October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 28 10th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9830452-1-2 the U.S. faced simple average duties of 4.8, 6.6, and 4.3 percent for non-agricultural products in the year 2007. 7 One may argue that even the most affected sectors can have only a minimal impact on overall production and export capacities if production in these sectors constitutes only a small percentage of aggregate production in the economy. 8 The relevant commodity export earnings as a percentage of total export earnings is based on data that is obtained from the International Financial Statistics (IFS) database. 9 For example, the monthly exchange rate data for Japan and the U.K. are available starting only in mid 1995. 10 The equity price data is based on the Jakarta SE Composite index for Indonesia, the Colombo SE All Share index for Sri Lanka, and the Bangkok S.E.T. index for Thailand. The equity prices for Japan, U.K., and the U.S. are based on the Nikkei 225 Stock Average, FTSE 100, and the S&P 500 Composite index respectively. 11 For the interest rate, we use the 3-month deposit rate for Indonesia and the money market rates for both Sri Lanka and Thailand. 12 Based on likelihood ratio tests, we find that the individual country effects are not necessary for all equity market estimations. Table 2 and Table 3 results therefore do not include fixed effects. 13 Likelihood ratio tests indicate that the individual country effects are significant to the model when the dependent variable is a measure of trade. Subsequently, Table 4 and Table 5 take into account fixed effects in the estimations. October 15-16, 2010 Rome, Italy 29