2. Understanding Touch - People at VT Computer Science

advertisement

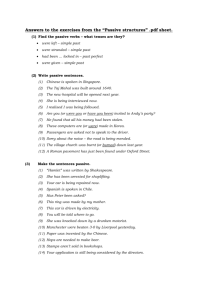

Touch Over A Distance: A Review of Affective Haptic Interface We present a review of literature regarding the digital mediation of social touch. We first explore the nature of touch as a physiological phenomenon, involving cutaneous and kinesthetic components. We proceed to examine the literature of the psycho-social aspects of touch. These literature generally agree that touch has meaning only within context. With context, touch is a direct medium for expressing intimacy and affection. Because of the importance of touch in interpersonal intimacy, researchers have proposed many haptic interfaces to mediate social touch. We reviewed a set of applications that have shown that mediated social touch has potentials in supporting interpersonal intimacy, enhancing a feeling of connectedness between individuals. Most applications, however serve to communicate simple ideas using symbolic haptic icons. A deficiency is that most affective haptic applications simply assume these benefits with little carefully designed empirical study. Based on physiological and social psychological literature on touch, we assess the current research and design efforts and propose future directions for the field of affective haptic interfaces. We propose that contextualizing touch with other interaction modalities, like voice and video, will help people to express affection more direct and accurate. 1. Introduction 1. Touch plays a very important role in the development of human perception and cognition. Besides, touch is particularly significant in social interactions. 2. However, the research of mediating touch in HCI is far from sufficient. Though there exists a set of empirical applications and design already[1-4], most of the applications and designs are lack theoretic support [5, 6]. Many fundamental questions are still under exploration. It is due to the complex of touch [7-9]. 3. In order to understand the meaning of touch in interpersonal communication and address affective haptic interfaces as a design problem, it is important for us to have a profound understanding of nature of touch as a physiological phenomenon as well as its psycho-social aspects. Paper Layout. 2. Understanding Touch 2.1 Touch as a physiological phenomenon 1. The modality of touch includes distinct cutaneous, kinesthetic and haptic systems that are distinguished on the basis of the underlying neural inputs [9]. The cutaneous receptors are embedded in the skin; the kinesthetic receptors lie in muscles, tendons, and joints; and the hpatic system uses combined inputs form both. In functional terms, the cutaneous sense provides an observer with information ab out stimulation of the skin surface; and kinesthesis provides static and dynamic information about the relative positioning of the head, torso, limbs and effectors used in touching [7]. The haptic system uses combined inputs from both the cutaneous and kinesthetic systems. 2. Another widely discussed distinction is between active and passive modes of touch in J.J. Gibson’s work[7, 10, 11]. Active touch is sensed by the person who initiates the touch, whereas passive touch is sensed by the person being touched. The difference between is the presence or absence of motor of control. It has been stated in Cullen’s work [12] that the reason of distinguishing these two modes is that human processes them differently in order to precisely guide motor control and achieve perceptual stability. 3. Loomis and Lederman proposed a taxonomy of touch which requires three important factors. They are (1) the type of information available to the observer, (2) the degree of control exerted by the observer in picking up stimulus information, and (3) the transparency of the linkage between efference and reafference. Loomis and Lederman combined Gibson’s criterion—active or passive mode of touch with the classification of sensory systems (cutaneous, kinesthetic and haptic system) [7] and yielded five “modes of touch”: cutaneous perception, passive kinesthetic perception, passive haptic perception, active kinesthetic perception, and active haptic perception. They summarized many of the studies that had investigated performance in active and passive conditions. Their summary indicates whether cutaneous information was used in the performance of task, if so the body locus and tactile mode of stimulation, whether kinesthetic information was available, if so, which body part was moved and whether the observer had control over sensing. The experiments on estimation and discrimination of roughness clearly show that roughness perception depends only upon cutaneous information. Similarly, the experiments on Braille reading indicate that active control and kinesthetic information are quite unimportant for the sensing characters. In most of the 2-dimensional pattern recognition studies, active touch has resulted in superior performance than passive touch, but in all such studies the passive touch condition involved only cutaneous stimulation. Thus one doesn’t know whether the superiority of active touch resulted from the control over sensing or the availability of kinesthetic information. Only in studies by Magee and Kennedy and by Bairstow and Laszlo was he comparison between active and passive conditions, in both of which afferent kinesthesis was available. Based on evidence so far, there seems to be no advantage in permitting the observer to control the pickup of the information. 2.2 Touch as a Psychological and Social phenomenon 1. Touch is important to the development of human [13, 14] 1.1 Touch is important in early childhood development. 1.2 Human need to touch or be touched throughout their adult years. 1.3 Some Systematic studies showed that being touched are beneficial for those who are ill. 1.4 Touching is also related to social and psychological adjustment among normal, healthy adults. 2. Touch Categories by Heslin 1974 [15] 2.1 Functional/professional 2.2 Social/polite 2.3 Friendship/warmth 2.4 Love/intimacy 2.5 Sexual/arousal 3. Meanings of touch [13] (haptics, wikipedia) Touch research conducted by Jones and Yarbrough (1985) revealed 18 different meanings of touch, grouped in seven types: Positive affect (emotion), playfulness, control, ritual, hybrid (mixed), task-related, and accidental touch. 4. Touch and context [13] Contextual factors are critical to the meanings of touch. The same behavior may have different meanings, depending on the context and different behaviors might have the same or similar meanings. The role of context in shaping meanings of touch has been ignored in the past research. In these researches, they conclude that ”specific touch gestures do not have universal meanings”. However, the meaning of touch could be uncovered if the context of each touch, including accompanying verbal statements and other elements of the social situation were examined. 2.3 Touch as a nonverbal communication modality 1. Touch, as a nonverbal behavior, has been studied using a nonverbal communication framework. Senders encode his information into the nonverbal behavior behavior while receivers decode the information 2. Research on the relationship between nonDifferent research efforts in defining “communication” [16, 17] 3. Mediated Touch Applications Examine the existing applications with focus on what kind of touch meaning is intended to be provided, how and the evaluation. Important: compare the existing applications with the research in psychology and communication. 4. Mediated Touch As A Design Problem References: 1. M. Adcock, M. Boch, V. Harden, D. Harry, and R.V. Poblano, “Tug n' Talk: A Belt Buckle for Tangible Tugging Communication,” Proc. CHI, 2007. 2. L. Bonnanni, J. Lieberman, C. Vaucelle, and O. Zucherman, “TapTap: a haptic wearable for asynchronous distributed touch therapy,” Proc. Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '06), 2006. 3. A. Chang, B. Resner, B. Koerner, X. Wang, and H. Ishii, “LumiTouch: an emotional communication device,” Proc. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2001. 4. C. Dodge, “The bed: a medium for intimate communication,” Proc. CHI '97 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems: looking to the future 1997, pp. 371 - 372 5. V. Hayward, O.R. Astley, M. Cruz-Hernandez, D. Grant, and G. Robles-De-LaTorre, “Haptic Interfaces and Devices,” Sensor Review2004. 6. A. Haans, and W. Ijsselsteijn, “Mediated Social Touch: A Review of Current Research and Future Directions,” Virtual Reality 2006, pp. 149-159. 7. J.M. Loomis, and S.J. Lederman, “What utility is there in distinguishing between active and passive touch,” Proc. Psychonomic Society meeting, 1984. 8. G. Collier, “Touch,” Emotional expression, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1985. 9. R.L. Kaltzky, and S.J. Lederman, “Touch,” Experimental Psychology, Handbook of phychology 4, A.F.a.P. Healy, R. W. ed., Wiley, 2002, pp. 147-176. 10. J.J. Gibson, “Observations on active touch,” Psycholgical Review 1962, pp. 477490. 11. J.J. Gibson, The senses considered as perceptual systems, Houghton Mifflin, 1966. 12. K.E. Cullen, “Sensory signals during active versus passive movement ” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2004, pp. 698-706 13. S.E. Jones, and A.E. Yarbrough, “A naturalistic study of the meanings of touch,” Communication monographs1985. 14. V.S. Clay, “The Effect of Culture on Mother-Child Tactile Communication,” The Family Coordinator1968, pp. 204-210. 15. R. Heslin, “Steps toward a taxomony of touching,” Proc. The annual meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, 1974. 16. P. Watzlawick, and J. Beavin, “Some formal aspects of communication,” ABI/INFORM Global 1967, pp. 4-8. 17. M. Wiener, S. Devoe, S. Rubinow, and J. Geller, “Non-verbal behavior and nonverbal communication,” Psychological review1972.