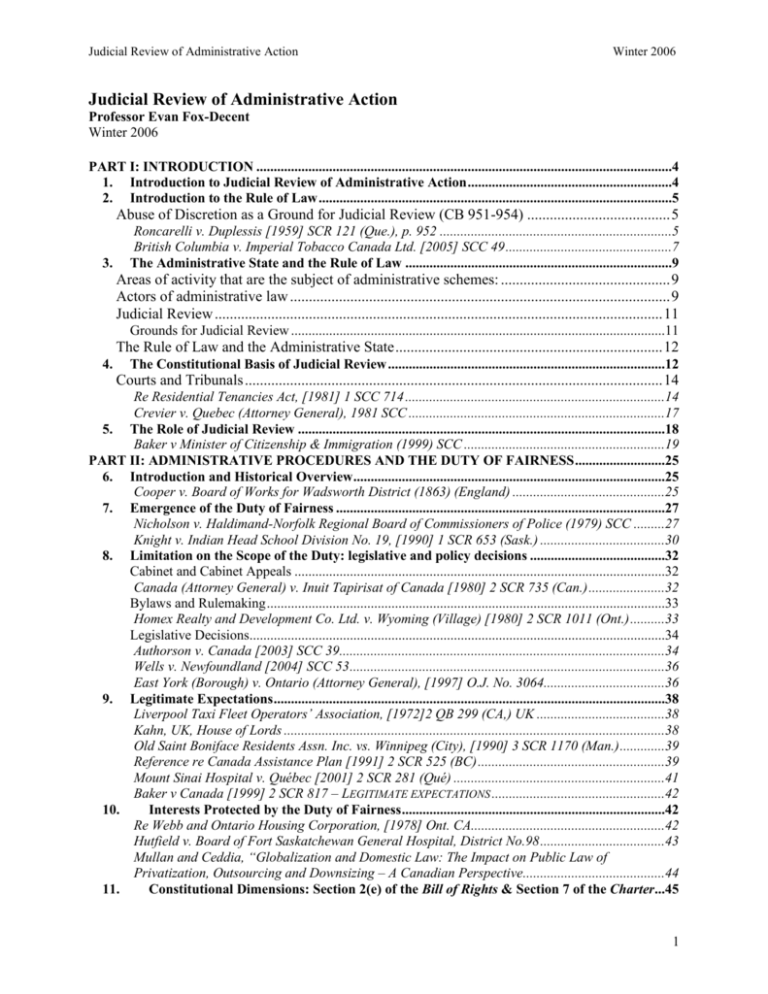

Judicial Review Of Administrative Action

advertisement