assessment-of-damages-in-tort-and-contract

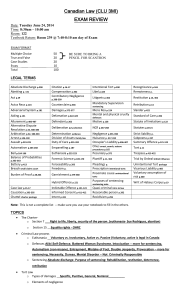

advertisement

The Differing Principles of Assessment of Damages in Tort and Contract By Raphael Kok 1. Introduction For those in the legal fraternity, the question of whether a legal wrong has been committed in various situations predominantly occupies their concentration. This holds true, even purely in the civil context. When confronted with a problem, the question that immediately blazes in their mind is this: “Is there a breach of tortious duty or a breach of contract here?” However, the layman’s perspective is a stark contrast. He is not interested in knowing whether it is a case of breach of tortious duty, or a breach of a contractual duty, or both. He is not interested in knowing how does a tortious or contractual liability arises. Instead, he is only interested in a single thing: compensation. His mind is only focused on a single question: “How much can I get out of this?” This is why the law of damages deserves meticulous analysis in any given civil case. And why any legal practitioner, wishing to serve his clients’ interest best, must command a firm grasp of the principles of assessment of damages in tort and contract. More importantly, he must appreciate the reality that there are essential theoretical and practical differences between the two. As Scrutton L.J. noted in The “Arpad”1: “It is often said that the measure of damages in contract and tort is the same; I do not think that this is strictly accurate”. Indeed, such differences affect both the question of recoverability and quantum. Conveniently, the approach in assessing damages in tort and contract are mainly identical. Thus, any differences in their principles can be analysed in parallel. Such principles can be divided into three categories i.e. (1) basis of compensation; (2) principles limiting compensatory damages; and (3) types of loss. They are by no means mutually exclusive, but instead may overlap each other. They are merely categorised as such to ease understanding to the law of damages and arguably, provide a practical step-by-step methodology for legal practitioners to approach the question of “How much can I get out of this?”. Next, the issue of concurrent liability arises. This issue has become more pertinent in light of the recent House of Lords decision of Henderson v Merrett Syndicates Ltd,2 where Lord Goff stated that ‘the common law is not antipathetic to concurrent liability, and that 1 2 [1934] P. 189 (CA), p. 216. [1995] 2 AC 145, p. 193-194. there is no sound basis for a rule which automatically restricts the claimant to either a tortious or a contractual remedy’. Also, concurrent liability cases are becoming more prevalent, due to the recent liberalisation of the tort of negligence to allow the recovery of pure economic loss (which has traditionally been confined to the contract realm) in not only situations of negligent misstatement,3 but also for negligent acts (particularly in cases of defective building liability) across the Commonwealth4 including Malaysia,5 but for the notable exception of England.6 In light of the progressive expansion of concurrent liability cases, the question of practical differences between assessment of damages in tort and contract becomes crucial. This is because understanding such differences would enable legal practitioners to determine how best to recover maximum damages i.e. either through an action in tort or contract. In short, this assignment analyses the different legal principles of assessing damages in tort and contract, and the resulting practical differences when such principles collide in concurrent liability cases. 2. Basis of Compensation Generally, the basis of awarding damages, in both an action in tort or contract, is ‘to give the claimant compensation for the damage, loss or injury he has suffered’ 7 or alternatively, ‘to put the claimant in the position that he would have occupied if the wrong had not been done’.8 Such an overarching proposition is not wrong. However, it overlooks the fundamental premise of all contractual claims i.e. the existence of an enforceable contract.9 In such light, and for practical purposes, we can narrow our outlook to distinguish the compensatory aims for damages in tortious and contractual breaches. 2.1. Tort 3 See, for example, Hedley Bryne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners [1964] AC 465 (HL); Caparo Industries plc v Dickman [1990] 1 All ER 568 (HL); White v Jones [1995] 2 AC 207 (HL). 4 In Australia, see Bryan v Maloney [1995] ALR 163 (HC); in Canada, see Winnipeg Condominium Corporation v Bird Construction Co Ltd [ 1995] 121 DLR 193 (SC); in New Zealand, see Invercargill City Council v Hamlin [1996] All ER 756. 5 See Majlis Perbandaran Ampang Jaya v Steven Phoa [2006] 2 MLJ 389 (FC) and Dr Abdul Hamid Abdul Rashid v Jurusan Malaysia Consultants [1997] 1 AMR 637 (HC). 6 See Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1991] 1 AC 398 (HL). 7 McGregor H., McGregor on Damages, 17th ed, London: Sweet & Maxwell, , 2003 (“McGregor”), p. 12. 8 Waddams, S.M., The Law on Damages, Toronto: Canada Law Book Limited, 1983 (“Waddams”), p. 684. See also Burrows A., Remedies For Torts and Breach of Contract, 3rd ed., Oxford University Press, 2004 (“Burrows”), p. 33. 9 Ibid. In damages for tortious breaches, its compensatory aim is ‘to put the claimant into as good a position as it would have been in if no tort has been committed’.10 A classic statement of this is found in Livingstone v Raywards Coal Co,11 where Lord Blackburn explained that the measure of damages in tort is ‘to put the party who has been injured in the same position as he would have been in if he has not sustained the wrong for which he is now getting his compensation’. 2.2. Contract In damages for contractual breaches, its compensatory aim is ‘to put the claimant into as good a position as it would have been in if the contract has been performed’. As Parke B in Robinson v Harman12 succinctly puts it: ‘the rule of common law is that where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract, he is to be placed in the same situation with respect to damages as if the contract has been performed’. Such a view was echoed in the Malaysian case of Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat v Plenitude.13 2.3. Practical Differences in Concurrent Liability Cases Such theoretical differences between the compensatory aims for damages in tortious and contractual breaches can give rise to practical differences, in terms of the recoverable quantum of damages, in concurrent liability cases. In short, pursuing an action in tort or contract in such cases may produce different results in the total quantum of recoverable damages. Burrows illustrates this emphatically in the case of a contract entered in reliance of a tortious misrepresentation:14 Imagine that a claimant buys a car for $5,000 from a salesman who falsely misrepresents that the car is one-year old (which, if true, has a market value of $5,500), when it is actually four-years old (which has a market value of $4,000). If the claimant keeps the car and sues in tort, he should be put into ‘as good a position as if he had never entered the contract’. His damages would be $5,000 - $4,000 = $1,000. If the claimant instead sues in contract, he should be put into ‘as good a position as the contract had been performed based on the statement’. His damages would be $5,500 - $4,000 = $1,500. If, however, the market value of a one-year old car is $4,500 instead, the claimant would gain more in damages if he 10 Burrows, p. 33. (1880) 5 App Cas 25, p. 39. 12 (1848) 1 Exch 850, p. 855. 13 [1995] 1 AMR 41; [1994] 3 MLJ 777 (FC). 14 Burrows, p. 34. 11 sued in tort as his damages would still be $1,000, but reduced to $4,500 - $4,000 = $500 if he sued in contract. This clearly shows that in specific concurrent liability cases, different quantum of damages are recoverable, depending on whether a claimant sues in tort and contract. The example also shows that when a claimant makes a good bargain, as in the first situation, he would be better off suing in contract. But when he makes a bad bargain, as in the second situation, he would be better off suing in tort.15 3. Principles in Limiting Compensatory Damages Although it is a ‘general rule’ for the compensatory aim of damages in tort and contract to put the claimant in a position as if the wrong was never committed,16 this does not automatically result into the defendant bearing all the burden of restoring him into such a position.17 Instead, the law places limitations to ‘reduce damages that full adherence to the compensatory aims would dictate’, based on certain principles i.e. (1) remoteness; (2) intervening cause; (3) duty to mitigate; and (4) contributory negligence.18 3.1. Remoteness Whether a breach is tortious or contractual, a principal restriction on compensatory damage is that the loss sought to be claimed by the claimant must not be too remote from the breach of such duty.19 The essential rationale behind this principle is that ‘it is unfair to a defendant, and imposes too great a burden, to hold it responsible for losses that it could not have reasonably contemplated or foreseen’.20 3.1.1. Tort The test of remoteness used in tort is none other than the famous ‘reasonable foresight’ test.21 Propounded by Viscount Simonds in Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Morts 15 Ibid McGregor, p. 15 17 Id, p. 15 and 75. 18 Burrows, p. 73. 19 Id, p. 76. 20 Ibid. 21 Although primarily a test used in the tort of negligence, it has been also applied in cases of nuisance (see Overseas Tankship (UK) v Miller SS Co Pty Ltd (The Wagon Mound No 2) [1967] 1 AC 617) and strict liability (see Cambridge Water Co v Eastern Counties Leather plc. [1994] 2 AC 264). Its applicability to intentional torts is yet debatable (see Burrows, p. 81). 16 Dock & Engineering Co Ltd, The Wagon Mound,22 it is a ‘principle of civil liability that a man must be considered to be responsible for the probable consequences of his act’23 and as such, ‘it is the foresight of the reasonable man which alone can determine responsibility’.24 Such a test only ‘bars recovery for unreasonable types of damage’.25 Thus, so long the damage is a type which is foreseeable, it can be recovered even if the degree of damage is unforeseeable26 or if the precise manner in which the damage occurs is unforeseeable.27 So what degree of likelihood of the loss occurring is required under the test? Rarely addressed in tort cases themselves,28 the answer can be found instead in contract cases. In Koufos v Czarnikov Ltd, The Heron II,29 the House of Lords held, in contrast with the contract test of remoteness, that the tort test requires only a low degree of likelihood of loss to be reasonably foreseeable. Similarly in H Parsons Ltd v Uttley & Co Ltd, 30 Lord Denning described the degree of likelihood as ‘a slight possibility’. 3.1.2. Contract The contract test for remoteness is commonly known as the ‘reasonable contemplation’ test. It originated from Hadley v Baxendale,31 where Alderson B held that losses from contractual breaches can only be recovered if they ‘arise naturally, i.e. according to the usual course of things from such breach of contract’ or when they ‘may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties at the time they made the contract as the probable result of the breach of it.’ The Court of Appeal in Victoria Laundry (Windsor) Ltd v Newman Industries Ltd32 later combined both rules into a single rule based on ‘reasonable contemplation’, but seemed to suggest that it was similar to the ‘reasonable foresight’ test. Predictably, the latter view was subsequently criticised in Heron II,33 where Lord Reid stated that the proper test was whether the loss is ‘of a kind which the defendant, when he made the contract, ought to have realised was not unlikely to result from the breach’, and Lord Upjohn similarly reiterating that damages ‘should depend on assumed common 22 [1961] AC 388 (PC) Id, p. 422-423 24 Id, p. 424. 25 McGregor, p. 150. 26 See, for example, Vacwell Engineering Co Ltd v BDH Chemicals Ltd [1997] 1 QB 88 27 See, for example, Hughes v Advocate [1963] AC 837. 28 Burrows, p. 80. 29 [1969] 1 AC 350. 30 [1978] QB 791. 31 [1854] 9 Exch 341, p. 354 32 [1949] 2 KB 528, 539-540 33 [1969] 1 AC 350, p. 382-383 (per Lord Reid), p. 422 (per Lord Upjohn) 23 knowledge or contemplation and not on foreseeable but most unlikely consequence’. In short, a stricter test than the ‘reasonable foresight’ test should be applied. This then begs the question: how different is the degree of likelihood of loss required for both tests? Despite the Law Lords’ best efforts in Heron II, there was no coherent, definitive answer to this. Burrows’ educated guess is that ‘while a slight possibility of the loss occurring is required in tort, a serious possibility of the loss occurring is required in contract’.34 The rationale for applying a stricter remoteness test for contract is essentially an issue of contractual relationship and knowledge. As explained by Lord Reid in Heron II, ‘in contract, if one party wishes to protect himself against a risk which to the other party would appear unusual, he can direct the other party’s attention to it before the contract is made’, whereas ‘in tort, there is no opportunity for the injured party to protect himself in that way’.35 But this was not the end of judicial development of the contract test of remoteness just yet. In Parsons v Uttley Ingham,36 Lord Denning added a new spin to the law. He felt there was not just a single test, but instead two tests. The two tests is applied depending on the nature of the loss i.e. (1) physical harm or incidental expense; and (2) loss of profit or opportunities for gain.37 Where damages for physical harm is sought (as was the case here), Lord Denning held that the ‘reasonable foresight’ test applied, in that the degree of likelihood of loss required was ‘a possible consequence even if it was only a slight possibility’. 38 In contrast, only when damages for loss of profits is sought should the stricter ‘reasonable contemplation’ test apply, in that the degree of likelihood of loss required was contemplated by the parties ‘as a serious possibility or real danger’.39 As the cases of Hadley, Victoria Laundry and Heron II all dealt with loss of profits, this was why, in Lord Denning’s opinion, the latter test was applied in such cases. Why this novel way of distinguishing the remoteness test based not on the cause of action (tort or contract), but on the nature of loss? Lord Denning reasoned that ‘where a defendant is liable for his negligence to one man in contract and to another in tort, each suffers like damage’ and thus, ‘the test of remoteness is, and should be, the same in both’ 40. Also, according to Hart (of whom Lord Denning drew his analysis from) and Honore, both such losses should be treated separately as they essentially deal with different causation 34 Burrows, p. 88. [1969] 1 AC 350, p. 385-386. See also p. 411 (per Lord Hodson) and p. 422-423 (per Lord Upjohn) 36 [1978] QB 791. 37 See Hart H.L.A and Honore T., Causation In Law, 2nd ed., Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985 (“Hart and Honore”), p. 313-314. 38 [1978] QB 791, p. 802. 39 Ibid. 40 Id, p. 804. He also cited examples like product liability, occupier’s liability and medical negligence 35 considerations.41 As loss of profits are concerned with ‘hypothetical gains’, it is ‘reasonable to limit these to gains which would be made in circumstances likely to occur or contemplated by the parties’. In contrast, for physical harm (which would not have occurred but for the defendant’s earlier wrongful act), the question of damages is ‘more reasonably determined by considering not hypothetical events’, but the surrounding causal circumstances.42 In short, it is reasonable to use a stricter test for hypothetical pure economic losses, but not for actual physical harm caused by a contractual breach. Despite the force of such arguments, the majority in Parsons declined to adopt such a ‘dual’ remoteness test in contract. Scarman LJ stated, with whom Orr LJ concurred, that all losses are only recoverable in contract ‘provided the parties contemplated as a serious possibility the type of consequence that ensued the breach’.43 And recently in Brown v KMR Services Ltd., the majority’s view was affirmed.44 At any rate, both approaches to the remoteness test in contract are equally compelling. In Malaysia, Section 74 of the Contracts Act 1950 has been consistently held by the courts45 to encapsulate the Hadley v Baxendale rule. Unfortunately, the courts have made no definitive judicial pronouncement on which approach to be adopted. In light of strong judicial support in England, it appears that the Heron II approach would prevail. Nevertheless, it is submitted that Lord Denning’s and Hart’s approach is more sensible. 3.1.3. Practical Differences in Concurrent Liability Cases Due to the different remoteness tests applied in tort and contract, many interesting implications can result from concurrent liability cases. Firstly, let us take the prevailing law as it stands today i.e. that the Wagon Mound ‘reasonable foresight’ test is used in tort, while the Heron II ‘reasonable contemplation’ test is used in contract. The most obvious question which arises is this: in concurrent liability cases, which test is to be applied? The answer to this can be drawn from Lord Reid’s statements justifying the use of the ‘reasonable contemplation’ remoteness test in contract i.e. in a contractual relationship, parties have the opportunity to inform each other of any unusual risks requiring protection.46 It thus necessarily follows that when a tort action is brought in the context of a contractual relationship, the stricter ‘reasonable contemplation’ remoteness test should also apply, as the 41 Hart and Honore, p. 313. Id, p. 321. 43 [1978] QB 791, p. 813. 44 [1995] 4 All ER 598, p. 621 (per Stuart-Smith LJ) 45 See, for example, Toeh Kee Keong v Tambun Mining Co Ltd [1968] 1 MLJ 39 (FC); Malaysian Rubber Development Corp Bhd v Glove Seal Sdn Bhd [1994] 3 AMR 2407. 46 Refer to the third paragraph of Part 3.1.2. 42 parties have such a similar opportunity.47 In short, the stricter remoteness test in contract prevails over that in tort in concurrent liability cases. If, however, Lord Denning’s approach is to be considered, different implications are reached. As different remoteness tests are applied depending on the nature of loss, it is no longer even necessary to speculate what test to be used in tort, contract, or in concurrent liability. The only issue is whether the loss is of physical harm, or loss of profits. If the former loss is sought to be claimed, the Wagon Mound ‘reasonable foresight’ test applies, regardless of whether the loss is consequent to a contractual breach, tortious breach, or both.48 Similarly, if loss of profits is sought to be claimed, the Heron II ‘reasonable contemplation’ test applies, regardless the nature of the breach. Thus, in concurrent liability cases, as in purely a tort or contract case, the remoteness test to be used depends solely on the nature of the loss. 3.2. Intervening Cause Another limiting principle is that a claimant cannot recover damages for loss if an intervening cause, combining with the defendant’s breach of duty, breaks the chain causation between the loss and the breach.49 There are three main types of intervening causes i.e. (1) natural events; (2) conduct of third party; and (3) conduct of the claimant. The limiting principles of all such types of intervening causes are generally similar both in tort and contract. Thus, as there are neither any substantial theoretical nor practical differences between the two, no further discussion on this point will be pursued. 3.3. Duty to Mitigate The duty to mitigate is essentially a duty imposed upon the claimant to ‘take all reasonable steps to mitigate the loss consequent on the breach’50. He is thus debarred ‘from claiming any part of the damage which is due to his neglect to take such steps’. 51 Similarly like intervening cause, its basic principles are applicable in tort and contract, without any substantial differences. Thus, no further discussion on this principle will be pursued. 3.4. Contributory Negligence 47 See Burrows, p. 92. Id, p. 89. 49 Id, p.97. 50 British Westinghouse Electric v Underground Electric Rlys Co of London Ltd [1912] AC 673, p. 689. 51 Ibid. 48 As its name suggest, contributory negligence originated as a creature of tort. Where it once operated as a complete defence to many torts,52 it has now been relegated to a partial defence due to the passing of the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945 (‘LRCNA’) in England. Section 1(1) of the LRCNA provides that where a claimant suffers damage due to partly his own fault, his claim shall not be defeated, but the damages recoverable shall be reduced to such extent as the court thinks just and equitable having regard to the claimant’s share in the responsibility of the damage. In Malaysia, such a pari materia provision is found in Section 12(1) of the Civil Law Act 1956.53 3.4.1 Contract The applicability of contributory negligence as a defence in tort is axiomatic. The crucial question, instead, is whether it is similarly applicable as a defence in contract to enable the defendant to reduce the damages resulting from his contractual breach. For a long time, the courts were uncertain of the LRCNA’s applicability to contracts, and cases moved to either direction.54 It was only until the Court of Appeal case of Forsikringaktieselskapet Vesta v Butcher55 in 1989 that the uncertainty was resolved. Even then, the decision raised many criticisms and intensified the debate further. The Court of Appeal essentially adopted Hobhouse J’s solution and reasoning in the court below56 to the issue. In determining the applicability of the LRCNA, Hobhouse J firstly identified three categories of cases:57 (1) breach of a strict contractual duty; (2) breach of a contractual duty of care; (3) breach of contractual and tortuous duty of care.58 As such, it was held that contributory negligence can only be a defence for breaches of contract falling under category (3) cases (as was the case in Vesta). After Vesta, the English courts59 have consistently approved such an approach. In Malaysia, the High Court in Karintina Trading v Cornelder’s (Sabah) Sdn Bhd60 similarly 52 Id, 129. Although yet to be confirmed either by definitive judicial pronouncements or legislation, there are strong reasons, mainly due to policy, not to extend the principle to intentional torts. See McGregor, p. 90; Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping Corp (No 2) [2002] UKHL 43 (HL) (no defense for the tort of deceit). 53 Act 67 54 McGregor, p. 92. For support of LRCNA’s applicability to contracts, see Quinn v Burch Bros (Builders) [1966] 2 QB 839. For support of the contrary view, see Basildon District Council v J. E. Lesser (Properties) [1985] QB 839. 55 [1989] AC 852. The case went on appeal to the House of Lords, but the issue of contributory negligence was not addressed. 56 [1986] All ER 488. 57 Id, p. 508; affirmed in the Court of Appeal at [1989] AC 852, p. 860. 58 Burrows, p. 137 59 For an example of a category (1) case where contributory negligence was applied, see UCB Bank plc v Hepherd Winstanley and Pugh [1999] Lloyd’s Rep PN 963 (CA). In contrast, for examples of category (2) and followed Vesta, and held that since the wrong gave an action both in tort and contract, contributory negligence applied. Despite the law now being settled, serious criticisms can be levelled against such an approach. Essentially, such criticisms call for contributory negligence to apply as a defence to not only category (3) cases, but all other contract cases. 61 The first criticism is that it perpetuates an odd reversal of roles where a blameworthy claimant will be better off establishing that a defendant is only in breach of a strict contractual duty or a contractual duty of care, but not liable for negligence.62 Secondly, there should be nothing inherently wrong with reducing a claimant’s recoverability of damages because he was also partly at fault for his loss. As the law already provides that a blameworthy claimant can recover no damages due to his failure to mitigate his losses or his own actions constituting an ‘intervening cause’, it naturally follows that he should recover less damages due to his partial blameworthiness in causing his own loss.63 The final, and perhaps the most compelling criticism is that such an approach forces an ‘all-or-nothing’ injustice upon either the claimant or defendant.64 A perfect example where a claimant suffers from unfairness is the unreported Court of Appeal case of Schering Agrochemicals Ltd v Resibel NV SA.65 The facts were that the defendants breached their contractual duty by supplying defective equipments which caused a serious fire to break out at the claimant’s factory. However, the court held that as the plaintiff had either failed in their duty to mitigate their loss or broken the chain or causation by not properly maintaining their safety procedures in the factory, damages were irrecoverable Indeed, such a harsh result could have been avoided if the court was able to award damages reduced due to the claimant’s contributory negligence.66 Also, if the court had chosen to award full damages to the claimant, this then causes injustice to the defendants. In short, contract cases does not allow courts to choose a ‘mid-position’ which can best serve fairness in situations where both parties are blameworthy. Thus, it is submitted that the law needs to be reformed to allow contributory negligence to be used as a defence in contract cases. (3) case where it was not applied, see Raflatac Ltd v Eadie [1999] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 506 and Barclays Bank Plc v Fairclough Building Ltd [1995] QB 214 respectively. 60 [1995] 2 CLJ 604. 61 Support for the non-applicability of contributory negligence to purely contract cases is grounded upon fears that allowing its applicability would make contractual breach claims as complex disputes of comparative blameworthiness: See Burrows, p. 143 62 Burrows, p. 141. Much more discussion will be dealt in the next part. 63 Id. 64 McGregor, p. 95; Burrows, p. 141 and 143. 65 (26 November 1992, unreported). See Burrows, p. 141 for a summary of the facts and decision. 66 Burrows, p. 142. 3.4.2. Practical Differences in Concurrent Liability Cases Clearly, category cases (3) under Vesta refer to cases of concurrent liability. This would appear to bode well for the defendant in such cases. It does not matter if the claimant chooses to frame his action solely in contract, or if he also frames it in tort, but subsequently succeeds only in his action in contract. According to Vesta, the defence of contributory negligence would still apply in such cases.67 More interestingly is the role-reversal dilemma that a claimant faces. In contract cases closely resembling a category (3) case, the defendant will attempt to prove that the he was also liable in tort, while the plaintiff will attempt to prove the contrary.68As explained supra,69 the claimant gains more from denying that the defendant’s contractual breach is also a breach of tortious duty. It becomes truly a dilemma to a blameworthy claimant considering that he also has good reasons to pursue an action both in tort and contract as it would maximise his chances of establishing liability. In short, a blameworthy claimant in such a situation is faced with the dilemma of whether to: (1) play it safe i.e. sue both in tort and contract but risk recovering less damages than his actual loss; or (2) go for broke i.e. sue only in contract and stand to recover damages equivalent to his actual loss, but risk recovering nothing at all. 4. Types of Loss Lastly, it should be noted that there are restrictions on the recoverability of certain types of loss. The two types of losses which deserve discussion are: (1) loss of reputation; and (2) mental distress. 4.1. Loss of Reputation Loss of reputation is a non-pecuniary loss. It deals with society’s perception and feelings towards the claimant.70 Nevertheless, a claimant complaining of loss of reputation is generally not only concerned with the loss of reputation itself, but also the pecuniary loss flowing from it.71 67 See Burrows, p. 138; Palmer and Davies (1980) 29 ICLQ 415, p. 445. Burrows, p. 141. 69 Refer to the fourth paragraph of Part 3.4.2. 70 Burrows, p. 343 71 Ibid. 68 4.1.2. Tort Both loss of reputation and pecuniary loss flowing from it are recoverable for some torts.72 This is especially true for defamation, where its very basis is the protection of persons’ reputation,73 and for malicious prosecution.74 Generally, pecuniary loss flowing from loss of reputation is recoverable in all torts,75 but for some torts, notably negligence,76 loss of reputation itself is irrecoverable. 4.1.3 Contract For breach of contract, Addis v Gramophone Co Ltd77 is the leading authority that damages are irrecoverable for loss of reputation and any pecuniary loss flowing from it. Subsequently, cases have continued to deny recovery for the former, but allowed recovery for the latter, for certain types of cases.78 The first type is where the breach causes the claimant to suffer a ‘loss of income flowing from the loss of chance to enhance his reputation’,79 including the refusal to allow an actor’s appearance80 and to publish an author’s book.81 The second type is where the contractual breach causes a mismanagement of advertising.82 The third type is where a bank refuses to honour the claimant trader’s cheque.83 And the last type is where the defendant supplies goods below the standard required of the claimant’s customers.84 4.2. Mental Distress Mental distress covers, inter alia, frustration, anxiety, displeasure, vexation or tension.85 It is to be distinguished from psychiatric illness, and any mental distress consequent on personal injury or death.86 As will be explained infra, it is also closely related, but not identical, to physical inconvenience. 72 Id, p. 317. See McCarey v Associated Newspapers Ltd [1965] 2 QB 86, p. 108. 74 See Savile v Roberts (1969) 2 Ld Raym 374. 75 Burrows, p. 319. 76 See Calveley v Chief Constable of Merseyside [1989] AC 1228, p. 1238 77 [1909] AC 488. 78 See Aerial Advertising Co v Batchelors Peas Ltd [1938] 1 KB 269 where the court clearly distinguished the two types of loss. 79 Burrows, p. 313. 80 See Marbe v George Edwardes (Daley’s Theatre) Ltd [1928] 1 KB 269. 81 See Tolnay v Criterion Film Productions Ltd [1936] 2 All ER 1625. 82 See Aerial Advertising Co v Batchelors Peas Ltd [1938] 1 KB 269 83 See Robin v Steward (1854) 14 CB 595 84 See Anglo-Continental Holidays Ltd v Typaldos Lines (London) Ltd [1967] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 61. 85 Watts v Morrow [1991] 1 WLR 1421, p. 1445. 86 Burrows, p. 323-324. 73 4.2.1. Tort Mental distress is only recoverable if it is consequent on physical inconvenience in certain torts (e.g. false imprisonment and nuisance).87 However, it is irrecoverable most notably for negligence.88 4.2.2 Contract Again, Addis is the leading authority that damages are irrecoverable for mental distress for contractual breach. However, later cases have developed two exceptions to this general rule. Bingham LJ neatly identifies them in Watts v Morrow:89 (1) ‘when the very object of a contract is to provide pleasure, relaxation, peace of mind or freedom from molestation’; and (2) ‘mental suffering directly related to physical inconvenience’. The first exception includes most notably ruined holiday cases.90 The second exception includes cases of defective houses causing physical inconvenience (as was the case in Watts).91 4.2.3. Practical Differences in Concurrent Liability Situations As noted supra, mental distress for negligence is irrecoverable. However, it is possibly recoverable in concurrent liability situations. For example, in Watts, damages for both physical inconvenience and resulting mental distress were recoverable in an action in negligence and contractual breach. It is of course uncertain whether mental distress is recoverable if solely an action in tort was brought. But as long as there is a contract in which its object was to provide mental satisfaction, or that the mental distress is directly consequent on physical inconvenience, it is submitted that it should be recoverable. 5. Conclusion It should be appreciated that assessing damages in tort and contract is like navigating through a mazy labyrinth. Thus, it is paramount to know of the correct paths to take, and the traps that lurk in the shadows. Firstly, that the quantum of recoverable damages differs according to the perceived ‘position’ which the claimant seeks to be restored to. Secondly, that the remoteness test which limits recoverability of loss varies in tort and contract; the latter is stricter, and prevails in concurrent liability cases. Thirdly, that contributory 87 Burrows, p. 333. See McLoughlin v O’Brian [1983] 1 AC 410, p. 431. 89 [1991] 1 WLR 1421, p. 1445. 90 See Jarvis v Swan’s Tours [1973] QB 233 and the local case of Abdul Karim v T & R United [1987] Butterworth’s Law Digest 91 Watts v Morrow [1991] 1 WLR 1421 88 negligence cannot be used to reduce the quantum of damages in contract, except in concurrent liability cases, and this arguably produces injustice to contracting parties, and strange results in concurrent liability cases. And lastly, that there are additional restrictions of recoverability for certain types of loss. Nevertheless, the law of damages is still evolving. Lord Denning beckons us to depart from such well-trodden paths, and it may be that the better starting point to take, as suggested by Lord Hoffmann in Banque Bruxelles Lambert v Eagle Star Insurance,92 is by looking at the type of loss, rather the ‘position’ of the claimant. At any rate, all such eventualities must be known to the legal practitioner. For when approached by a lost wanderer, he must be ready to light the torch, and lead the way forward through the labyrinth. And he must be able to say, with confidence: “And that is how much you can get out of this.” 92 [1997] AC 191, p. 211