Feldman and Tyler

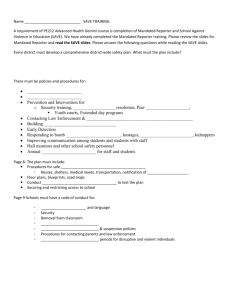

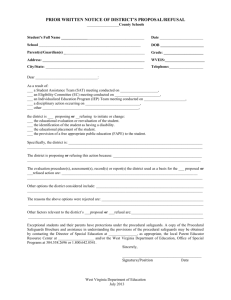

advertisement