Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general

advertisement

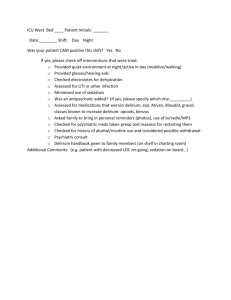

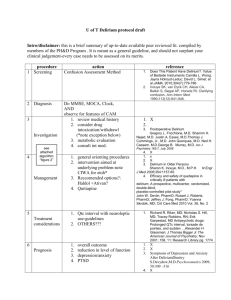

Guidelines for the diagnosis and Management of Older People with Delirium in a general hospital setting Reference Number N/A Version 1 Name of responsible (ratifying) committee Vulnerable Adults Committee Date ratified 07.07.2010 Document Manager (job title) Matron - Department of Medicine for Older People Consultant Geriatrician Date issued 17.09.2010 Review date July 2011 Electronic location PHT Multi-Professional Guidelines Related Procedural Documents Key Words (to aid with searching) Acute Confusion Drug Policy Falls Policy Delirium; Confusion Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 1 of 21 CONTENTS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. APPENDIX I APPENDIX II APPENDIX III APPENDIX IV APPENDIX V APPENDIX VI APPENDIX VII QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE INTRODUCTION PURPOSE SCOPE DEFINITIONS DUTIES AND RESPONSIBLITIES PROCESS TRAINING REQUIREMENTS REFERENCES AND ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTATION MONTORING COMPLIANCE WITH AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF, PROCEDURAL DOCUMENTS 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 12 12 FLOW CHART FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF DELIRIUM MINI MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION ABBREVIATED MENTAL TEST SCORE (AMT) SOME OF THE DRUGS / GROUPS THAT MAY PRECIPITATE DELIRIUM (THIS LIST IS NOT EXHAUSTIVE) DELIRIUM ADUIT TOOL DELIRIUM INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS AND RELATIVES THE CONFUSION ASSESSMENT METHOD (CAM) 37 14 15 16 13 17 18 19 21 Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 2 of 21 DELIRUIM Acute confusion is a sign that someone is physically unwell 1) SPOT IT • Sudden change in behaviour • More confused over the past few hours or days • Difficulty in following a conversation • Rambling and jumping from topic to topic • More sleepy or agitated than usual IF ANY ANSWERS ARE "YES" IT COULD BE DELIRUIM IF IN DOUBT CHECK IT OUT Risk factors for Delirium • Cognitive impairment • Sleep Deprivation • Immobility • Visual/hearing impairment • Dehydration Treat all the underlying causes 2) TREAT IT Remember the six common causes of Delirium: "Pinch me" Pain - Infection - Constipation - Hydration Medication - Environment • Withdraw all incriminating drugs • Correct biochemical abnormalities • Treat underlying infection 3) STOP IT EXPLANATION AND REASURANCE • Introduce yourself and explain what you are doing • Be calm and patient, avoid being confrontational • Use personalised care plans to communicate needs • Validate the persons feelings REORIENTATIONS • Gently reorient, reassure the patient of the time and date LOOK AFTER PHYISCAL NEED • Ensure dietary in take and fluids may need IV/Sc fluids • Check for signs of dehydration or pain • Ensure sensory aids are in good working order • Indentify and treat constipation Drugs AVOID SEDATION IF POSSIBLE – INCREASED RISK OF FALLS/DEATH • If severe agitation or hallucinations then See separate drug guidelines • If needed then start at low dose and review • Promote a normal sleep pattern ENVIRONMENT • Where possible avoid intra / inter hospital transfers • Avoid the use of bed rails or restraints • Reduce noise - Bed away from ward entrance/exit MONITOR DAILY If not improving seek expert medical and psychiatric advice. Record symptoms and AMTS/MMSE DISCHARGE PLANING Involve MDT and carers where appropriate. Ensure discharge AMTS/MMSE and Barthel recorded. Explain what has happened to the patient where appropriate Quick guide to the management of Delirium. Adapted from the unpublished work of Featherstone and Hopton university of Leeds 2007 Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 3 of 21 1. INTRODUCTION Delirium is common in hospitalised patients with a range between 10 and 50% reported in different studies1,2,3. It occurs most frequently in older people (up to 30% of older inpatients) but also commonly in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients4, in the alcohol dependent 5 and in the terminally ill6. It can occur in a wide variety of medical situations. Delirium is often not recognised by clinicians (missed in up to 2/3 of cases) and is frequently poorly managed7. Lack of recognition is important and may occur for a number of reasons including the fluctuating nature of it, overlap with dementia, lack of formal cognitive assessments being used, failure to appreciate the clinical consequences and failure to consider the diagnosis important7. It is vital that delirium is recognised and appropriately managed because patients who develop delirium have high mortality (twice as likely to die), institutionalisation and complication rates, and have longer lengths of stay than non-delirious patients (up to 8 days has been described)8. There is potential to prevent the onset of delirium in up to 30% of older in-patients9, 10. The National Service Framework for Older People (DOH 2001)11 identifies a fundamental requirement for the NHS to ensure the good and effective management of patients with mental health needs wherever they are being cared for. This document has been designed to assist clinicians in the achievement of this standard. The guidance contained within this document has been developed in line with the Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of Delirium in Older People, Royal College of Physicians, 200612, and also draws on the guidelines from the Isle of Wight health care trust 200513. Note: Clinician is used in reference to Doctors, Nurses and all members of the Multi-disciplinary team (MDT) 2. PURPOSE The following guideline aims to provide support for clinicians in the recognition, diagnosis and management of older people presenting with the symptoms of Delirium within the acute hospital environment, it is important to remember that patients with delirium can be found in all specialties of the hospital These guidelines do not specifically cover the management of withdrawal of alcohol. Appendix II provides quick reference guides to the guideline. 3. SCOPE This document is intended for the use of all staff involved in the care of patients identified as at risk or with a confirmed diagnosis of Delirium. The primary focus of the document has been developed around the care of older people, who are particularly prone to developing this condition. However the guidance may also be broadly applied to the treatment of acute confusion in younger patients. 4. DEFINITIONS Since it’s inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorder in 1987, Delirium has been the consensus term for the syndrome although it is also known as acute confusion. Delirium, is a disturbance of consciousness and cognition, with rapid onset (over hours to days usually), fluctuating course due to a cause such as a general medical condition, drug withdrawal or drug intoxication15. It is important to remember that Delirium is dangerous. Delirium can be treated and Delirium may be the only manifestation of severe disease (eg myocardial infarction) in an older person Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 4 of 21 There are four core features (which should all be present to make the diagnosis, although these may not always be easy to find) 1. Disturbance of consciousness (reduced awareness, reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention) 2. Disturbance of cognition such as a memory problem, disorientation or language problem 3. Develops over a short period of time and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day 4. Evidence from history, examination or laboratory results that it is caused by a general medical problem, substance intoxication or withdrawal16. In practice it is often the disturbance of cognition that is noticed and the other features, although present may not be identified by the clinician. Those with acute confusion should be managed in the same way as those fulfilling all the core features of delirium There are several subtypes of delirium recognised. These are hyperactive (pulling at clothing, restless, wandering, aggressive); hypoactive (more common, sleepy, difficulty following conversation, behaviourally not difficult and therefore the most common type to be missed) or a mixed picture where the patient may fluctuate between the two types described above17. It is important to recognise behaviours that can be associated with an underlying delirium which include: illusions/hallucinations, psychomotor disturbances as outlined above, altered sleep wake cycle, disorientation, restlessness, wandering, stripping off clothes, verbal aggression, physical aggression, refusal to eat/drink, inappropriate behaviour including sexual, an inability to co-operate or participate in care17. 5. DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Detail the duties, accountabilities and responsibilities (including level) of Directors, individuals, specialist staff, departments and committees. It is the responsibility of all clinical staff involved in the caring for patients with Delirium to follow the recommendations of this guideline. It is the responsibility of the Consultants, Matrons and Divisional Nurses to ensure that systems exist to enable staff to receive the training they require. 6. PROCESS 6.1 Causes of Delirium Up to a third of delirium is preventable9,16. Therefore awareness of risk factors, likely precipitating factors and the appropriate avoidance of these wherever possible are essential to reduce the development of the syndrome. Delirium is usually the result of the complex interaction of multiple conditions and risk factors. There is often a balance between risk factors and precipitating factors. For example, an older person with dementia may only require a relatively minor precipitant to become delirious, whereas in a young and usually fit person a major precipitant, such as severe sepsis, would need to occur before that person developed delirium. Table 118,19, outlines some of the major known risk factors and possible precipitants of delirium. These are not exhaustive lists Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 5 of 21 Table 1. Risk factors and precipitating factors Risk Factors Older age Existing chronic cognitive impairment or dementia Post General Anaesthesia Pain Polypharmacy Renal impairment Hepatic impairment Drug/ Alcohol withdrawal Surgery e.g fracture neck of femur Significant environmental change Multiple co morbidities Sensory impairment such as deafness, visual problems Precipitating factors for delirium Infection Drugs (any but particularly psychoactive drugs and drugs with anticholinerigic properties) Immobility, including the use of physical restraint Use of Bladder catheter Constipation Urinary retention Malnutrition Dehydration Electrolyte disturbance Pain Metabolic disturbance Severe illness Environmental change (ward transfer, lack of clock/watch) Sensory deprivation (hearing aid not working, glasses dirty/missing etc) (Adapted from Inouye et al 1993 and Inouye 2000) 6.2 Management of a patient with delirium This should include: Recognition of the condition Identification of underlying causes Treatment of underlying causes Management of the confusion and behaviour associated with delirium Recognition of the condition Diagnosing delirium can be difficult, and as previously highlighted, the diagnosis is frequently missed. In view of this the following are suggested12: Cognitive testing should be carried out on all older patients on to admission hospital and be entered into the patient’s notes. Serial measurements in patients at risk may help detect the new development of delirium or its resolution. Information, to include prior cognitive status wherever possible, should be sought from all available sources to include the patient’s carer or supporter, GP or anyone who knows them well. Clinicians are encouraged to make an initial assessment of the cognitive function by the use of a recognised screening tool such as the: Mini Mental State Examination20 (MMSE, see Appendix II), or the Abbreviated Mental Test score21 (AMTS see Appendix III). Clinicians are encouraged to support the test with information for the patient and their cares in the form of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) - a guide for people with dementia and their carers can be found on the Alzheimer’s Society website (www.alzheimer.org.uk/factsheet/436)22. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 6 of 21 However cognitive tests by themselves cannot distinguish between delirium and other causes of cognitive impairment. Dementia and delirium frequently occur together and it can be particularly difficult to distinguish between them when a patient presents acutely. It is frequently the situation that underlying confusion from dementia is worsened by an episode of delirium. IT SHOULD BE ASSUMED THAT ALL PATIENTS PRESENTING ACUTELY WITH CONFUSION ARE DELIRIOUS UNTIL PROVEN OTHERWISE TO AVOID TREATABLE CONDITIONS BEING MISSED. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) can be used to formally diagnose delirium (see Appendix VII). In many cases patients suffering from Delirium will be unable to provide a complete and detailed history. Therefore an exploration of pre-admission state from a relative or carer may prove invaluable and is an essential part of the assessment. Having established a baseline, further serial measurements should be undertaken as a means to detect any improvement or deterioration in the status of cognitive function (suggested at least twice a week or when there are significant changes in the condition) Identification of the underlying cause(s) History Common causes of delirium include any physical illness, medication (particularly those with anticholinergic side effects) or withdrawal from alcohol or drugs23. See appendix IV for a list of some of the drugs that may precipitate delirium. Many patients with a confused state are unable to provide the necessary information. Therefore information should always be sought from someone who knows the patient well to contribute to a more comprehensive assessment. In addition to standard questions in the history, the following information should be specifically sought. Full drug history including non prescribed drugs and recent changes Alcohol history Benzodiazepine use (avoid rapid withdrawal) Previous intellectual function (e.g. ability to manage household affairs) Functional status (e.g. actives of daily living) Onset and course of confusion Previous episodes of acute or chronic confusion Symptoms suggestive of underlying cause (e.g. infection) Sensory impairments Bowel habits Examination Physical examination can be difficult and may be needed to be completed in stages. Be aware of your approach to the patient (see section 7.4 management of confusion). Full examination should be undertaken with particular reference to the following: Neurological examination, level of consciousness Nutritional status (clinical evidence plus MUST score) Clinical evidence of dehydration Evidence of pyrexia or hypothermia (beware that older patients with sepsis do not always mount a pyrexia) Evidence of alcohol/ substance use or withdrawal PR Examination for constipation should be considered Cognitive function using a standardised screening tool e.g AMTS, MMSE Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 7 of 21 Investigations The following investigations are almost always indicated in patients with delirium in order to identify the underlying cause: Full blood count, C Reactive Protein or ESR, urea and electrolytes, calcium and phosphate, liver function tests, glucose Chest X-ray and pulse oximetry ECG Urinalysis Thyroid function tests (if not done within the last six months) Other investigations may be indicated according to the findings from the history and examination. These include: Blood cultures, B12 and folate, Magnesium, Arterial blood gases, Specific cultures eg urine, sputum CT head (see below) Lumbar puncture (see below) EEG (see below) CT Scan Although many patients with delirium have an underlying dementia or structural brain lesion (e.g previous stroke), CT has been shown to be unhelpful on a routine basis in identifying a cause for delirium18 and should be reserved for those patients in whom an intracranial lesion is suspected. Indications for the use of CT scanning should be discussed with a senior clinician (SpR level or Consultant) Focal neurological signs Confusion developing after head injury Confusion developing after a fall Evidence of raised intracranial pressure Lumbar puncture Routine Lumbar puncture is not helpful in identifying an underlying cause for the delirium 24. It should therefore be reserved for those in whom there is reason to suspect a cause such as meningitis or encephalitis. This might include patients with the following features: Meningism Headache and fever EEG Although the EEG is frequently abnormal in those with delirium, showing diffuse slowing 25, its routine use as a diagnostic tool has not been fully evaluated. However it can be useful when a medical cause cannot be found; if the EEG is abnormal it will identify the need to carry on looking for a cause EEG may also be useful where there is difficulty in the following situations (after discussion with an Spr or Consultant): Differentiating delirium from non-convulsive status epilepticus and temporal lobe epilepsy Differentiating delirium from dementia Identifying those patients in whom delirium is due to a focal intracranial lesion Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 8 of 21 Treatment of underlying cause The most important approach to the management of delirium is the identification and treatment of underlying cause(s). It is common for there to be more than one contributing factor. Therefore it is important that all possible causes are actively managed concurrently. Incriminating drugs should be withdrawn wherever possible26. Many drugs can precipitate delirium and any recent changes/additions should be considered a possible contributing factor. Appendix IV outlines some of these but is not exhaustive Drugs with anticholinergic activity (many drugs in common use, including benzodiazepines, have some anticholinergic effects and it is not always possible to avoid them all and their contribution to delirium should be balanced with their other required effects. Appendix IV outlines some drugs that may precipitate or worsen delirium, many of them through anticholinergic activity Correct biochemical abnormalities promptly27 Treat underlying infection (please refer to the guidelines from Microbiology with regard to potential prescription of antibiotics). Avoid Constipation – monitor bowel habit daily Avoid Catheters- where possible Management of Confusion Non Pharmacological Management In addition to treating the underlying cause, management should also be directed at the relief of the symptoms of confusion/delirium. The patient should be nursed in a good sensory environment with a multi-disciplinary approach to individualised care7,8,9,16,18,28-33. This includes:Improve communication Be aware of the person’s life biography – this may give you cues for conversational topics and prevent anxiety Verbal – Do not confront. Confused people are more likely to become agitated and aggressive if they feel threatened. Communicate clearly, calmly, simply and express your wish to help with their situation to reduce their distress/confusion. Introduce and personalise yourself to the person. Listen to the person, observe the behaviour and try to interpret the message, emotion and feelings being communicated. Try to avoid commands and the words ‘don’t’ and ‘why’. Explain to the person what you want them to do – not what not to do. Acknowledge their feelings and show concern. More than one member of staff talking to the person at the same time will add to the confusion and lose the thread of intervention. It may also serve to make the person feel threatened. Try to orientate the person and highlight visual clues for them to acknowledge. If the patient insists they are somewhere else, e.g. show other patients in beds. Validate/acknowledge their feelings and do not proceed with reality orientation as this could provoke a confrontation. Engage with the person in meaningful interaction offer distraction and diversions Explain unfamiliar noises/equipment/personnel to the person to avoid misinterpretation. Do not label a person or their behaviour in a negative way to others. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 9 of 21 Non-verbal – Open-handed gestures are seen as non-threatening, whereas pointed gestures are invariably seen as aggressive. Offering a handshake will be recognised by a confused person as a friendly gesture. If a person refuses to shake hands, this may indicate to the nurse that hostility and potential aggression are likely. Approach the person from the front, slightly off-centre to avoid feelings of confrontation. Maintain good eye contact and initial distance of approx. three feet, so as not to invade personal space. If the person is in bed or seated, avoid standing over them and, where possible, crouch down to their eye level. Non-verbal clues such as facial expression, body posture and eye contact will be taken on board by the patient and will override verbal communication Favour high-quality sleep Non pharmacological sleep promotion; noise reduction; use of low level lighting; avoidance of constant lightening; Maintenance of a normal sleep- wake cycle. If liked use milky drinks at bedtime. Limit sensory underload or overload Screen for visual and hearing impairment; provision of visual and hearing aids; Lighting level appropriate for time of day; avoidance of rooms with no windows. Where possible elimination of unexpected and irritating noise e.g. pump alarms. Involve and inform significant others Explain the cause of the confusion to relatives. Encourage family to bring in familiar objects and pictures form home and participate in rehabilitation Avoid malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies Nutritional support and/ or vitamin supplements of high-risk groups. Good diet, fluid intake and mobility to prevent constipation. Favour mobilisation Avoidance of immobilisation; Limit the use of Catheter and intravenous line. Early mobilisation evaluation by physiotherapist if appropriate. Check the physical needs of the patient Do they need to use the toilet, are they hungry, thirsty, constipated, in urinary retention, or in pain? Wandering People wander for a variety of reasons. Patients that wander require close observation within a safe and reasonably closed environment. Wandering is a meandering activity that appears to some observers to be aimless or repetitive that may expose the person to harm. This could be a pleasurable or distressing experience and can take the form of lapping, pacing, seeking, searching or foraging19. The least restrictive option should always be used when acting in the best interest of the patient20. Avoid physical restraint whenever possible 35 Environment Inter and intra ward transfers should only be considered for clinical management reasons. Specifically patients with delirium should NOT be moved to outlying areas without senior medical consultation (SPR and above) Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 10 of 21 Pharmacological management of confusion For information on drug use refer to drug guidelines for acute confusion in the older person Drug sedation may be necessary in the following circumstances12 In order to carry out essential investigations or treatment To prevent the patient endangering themselves or others To relieve distress in a highly agitated or hallucinating patient 6.3 Capacity Assessment and the Mental Capacity Act The Mental Capacity Act 2005 came into full force in October 2007 and provides a framework for decision making when a patient lacks capacity. Some patients with delirium may lack capacity and this will need to be assessed Under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, someone lacks capacity when the following criteria are met: Does the person have an impairment of, or a disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain? Does the impairment or disturbance mean that the person is unable to make a specific decision when they need to? For this test, a person is unable to make a decision (i.e. lacks capacity) if they cannot: Understand information about the decision to be made; Retain information about the decision to be made; Use or weigh that information as part of the decision-making process; Communicate their decision. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 states that an action or intervention is lawful if the decision maker has a reasonable belief that the patient lacks capacity and that the action is in the patient’s best interests (assuming there is not a valid advance decision by the patient, or a relevant lasting power of attorney or court appointed deputy) Under the Mental Capacity act, a patient lacking capacity can be restrained where there is a reasonable belief that it is necessary to prevent harm to them and the restraint used must be proportionate to the risk and of the minimum level necessary to protect the incapacitated person If a health professional needs to sedate a patient without capacity then they should document their belief that the patient does not have capacity in the medical records, document why the intervention is in the patient’s best interests and date, time and sign the entry. 6.4 Discharge arrangements The discharge documentation should clearly state that the patient has had an episode of delirium and all the likely precipitants of this. Cognitive testing should be done close to discharge (AMTS or MMSE) and recorded on the discharge documentation. Some patients with delirium may be traumatised by the experience12 and where possible the diagnosis should be explained to the patient (and or next of kin where appropriate) and verbal support and advice offered. Appendix VI outlines a some information from the Royal College of Psychiatrists 36 which may be useful for patients who have experienced delirium and their relatives. It emphasises the importance of spending time with a patient who has experienced delirium to explain to them what has happened and why which can be of relief to patients. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 11 of 21 7.TRAINING REQUIREMENTS All staff will need to show evidence of having read the guideline. Each department will need to evidence a roll out program for the guideline supported by inter-department training. Training sessions will be run by DMOP practice educator and will feed into DMOP RN induction and the trust RN induction. The guideline will also need to feed into the doctors trust induction. 8. REFERENCES AND ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTATION 8.1 References 1. Bhat, R.S., Rockwood, K. (2002). The prognosis of delirium. Psychogeriatrics, 2 (3): 165179. 2. Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN. (1990). A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA; 263:1097-1101. 3. Lindesay, J., Rockwood, K. and Rolfson, D. The epidemiology of delirium. In Delirium in Old Age. Eds. Lindesay, J., Rockwood, K., Macdonald, A. (2005). Oxford University Press; 2002 pp 27-50. 4. Jackson, J.C., Mitchell, N, & Hopkins R.O.(2009) Cognitive functioning, mental health, and quality of life in ICU survivors: an overview .Critical Care Clinics. 25:3 615-628. 5. DeBellis, R, Smith, BS, Choi, S & Malloy, M. (2005). Management of Delirium Tremens. Journal of Intensive Care Med. 6. Plonk, W M Arnold R M. (2005). Terminally ill. Journal of palliative medicine. 8:1042-1054 7. Young L & George j (1999) Guidelines for the management of Delirium in the Elderly. British Geriatric Society: London. 8. Marcantonio (2002) The management of delirium. In Delirium in Old Age. Eds. Lindesay, J., Rockwood, K., Macdonald, A. Oxford University Press. p.p. 123-151. 9. Marcantonio, E.R., Flacker, J.M., Wright, R.J., Resnick, N.M. (2001). Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomised trial. JAGS 2001; 49: 516-522. 10. Inouye, S.K., van Dyck, C., Alessi, C.A., Balkin, S., Siegal, A.P. and Horwitz, R.I.(1990) Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine;113: 941-8. 11. The national service framework for older people. (2001) Department of Health. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidanc e/DH_4003066 12. British Geriatrics Society (2006) Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people in hospital. Retrieved September 2006, from the British Geriatric Society website: www.bgs.org.uk 13. Peck, S. (2005) (2nd Ed) Clinical Guideline for the are and Treatment of OlderPeople with Delirium in a General Hospital Setting. Isle of White Healthcare NHSTrust. 14. Siddiqi N, Stockdale R, Britton AM, Holmes (2007) Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Issue 2:CD005563 15. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, Leo-Summers L, Acompora D, Holford TR and Cooney LM. A multi-component intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalised older patients. NEJM 1999; 340:669-676 16. Britton AM,Hogan-Doran JJ Siddiqi N (2006) Multidisciplinary Team interventions for the management of delirium in hospitalized patients (protocol). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Issue 2:CD005995 17. Inouye S, Viscoli C, Horowitz R, Hurst L, Tinetti M. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Int Med 1993;119:474-481. 18. Inouye, S. Prevention of delirium in hospitalised patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine.2000;13: 204 – 212. 19. Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. “Mini Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12: 189 – 198. 20. Jitapunkul S, Pillay I, Ebrahim S. The abbreviated mental test: its use and validity. Age & Ageing 1991;20:332-336. 21. Alzhemiers (2202) The mini mental Stte examination (MMSE) a guide for people with dementia and their carers. Retrieved July 2007, from the Alzhemiers society website: www.alzheimer.org.uk/factsheet/436 Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 12 of 21 22. Warshaw G, Tanzer F. The effectiveness of lumbar puncture in the evaluation of delirium and fever in the hospitalized elderly. Arch Family Med 1993;2:293-297. 23. Jacobsen SA, Leuchter AF, Walter DO. Conventional and quantitative EEG in the diagnosis of delirium among the elderly. J Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1993;56:153-158. 24. Casarett, D.J., Inouye, S.K. Diagnosis and Management of Delirium near the end of life. Ann. Intern. Med 2001;135: 32-40. 25. George, J., Bleasdale, S. and Singleton, S.J. Causes and prognosis of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a district general hospital. Age and Ageing 1997; 26: 423-427. 26. Landefield CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowel J. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. NEJM 1995;332:1338-1344. 27. Milisen, K., Foreman, M.D., Abraham, I.L., DeGeest, S., Godderis, J., Vandermeulen, E., Fischler, B., Delooz, H.H. A nurse led interdisciplinary programme for Delirium. JAGS 2001;49 (5): 523-532. 28. Philp I,and Appleby L Securing better mental health for older adults. 2005. Department of Health, London 29. Lundstrom, R.N., Edlund, A., Karlsson, S., Brunnstrom, B., Bucht, G., Gustafson, Y. A multifactorial intervention program reduces the duration of delirium, length of hospitalisation and mortality in delirious patients. JAGS 2005; 53: 622-628. 30. Britton, A., Russell, R. (2003). Multidisciplinary team interventions for delirium in patients with chronic cognitive impairment (Cochrane Review) in The Cochrane Library, Issue 4; Chichester UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. 31. McClusker, J., Cole, M., Abrahamowicz, M., Han, L., Podoba, J., Ramman-Haddad, L. Environmental risk factors for delirium in hospitalised elder people. JAGS 2001; 49: 1327 – 1334 32. Naughton, B., Saltzman, S., Ramaan, F., Chadha, N., Priore, R., Mylotte, J. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the prevalence of delirium and shorten hospital length of stay. JAGS 2005; 53: 18 – 23. 33. O’Keeffe, S.T. Down with bedrails? Lancet 2004; 363; 343-4 34. Mental Capacity Act (2005) the Stationery Office London 35. Featherstone, I & Hopton, A (2007). Stop Delirium! Liaison Psychiatry for Older People Conference. 36. Delirium Factsheet (2009). Royal college of Psychiatrists. Retrieved Nov 2009, from the Royal college of Psychiatrists website: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mentalhealthinfo/problems/physicalillness/delirium.aspx 37. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. Am Coll Phys 1990;113:941-8 8.2 Relating policy and guidelines – to read in association with this guideline Decision-making for people who lack mental capacity Policy Acute confusion and aggression in Older People on Medicine for Older People wards – Guidelines on management Clinical policy & associated guideline for the assessment, prevention and management of adult in-patients at risk of falling or who have already fallen Clinical policy for the use of bedside rails Acute Alcohol withdrawal 9. MONITORING COMPLIANCE WITH, AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF, PROCEDURAL DOCUMENTS A base line audit (appendix V) should be completed before implication of the guideline and a subsequent audit should be completed every six months to ensure that standards are improving. The responsibility for monitoring should be identified with in each department and audit reports fed in to divisional governance structures. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 13 of 21 APPENDIX I: FLOW CHART FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF DELIRIUM PATIENT IDENTIFIED WITH POSSIBLE ACUTE CONFUSION/DELIRIUM MAKE A COGNITIVE ASSESSMENT – AMTS/MMSE/CAM Confusion is a symptom not a diagnosis. Delirium/acute confusion can occur in a patient with knwn dementia. Delirium is dangerous (mortality and institutionalisation doubled, LOS increased). Delirium can be treated. Delirium may be the only manifestation of significant acute disease in an older person Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 14 of 21 APPENDIX II: MINI MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION20 Assessment Part One 1. Orientation for time Day, Date, Month, Season, Year 2. Orientation for place Country, County, City/Town, Hospital, Name of ward/unit 3. Registration of three words Please repeat 3 words, eg, ball, jar, fan. Repeat 3 words up to 5 times until they are learned Spell WORLD backwards 4. Attention/concentration 5. Short term memory Part Two Method 6. Language 7. Construction Task Tell me the three items we named a few minutes ago a) Point to a pen, a wrist watch and ask the patient to name them b) Repeat the phrase, `no ifs, ands or buts’ c) Tell the patient to follow the instructions: `Take this piece of paper in your right hand, fold in half and put on the floor’ d) Show the patient a piece of paper with the words, `CLOSE YOUR EYES’ written on it and ask them to follow the instructions e) Ask the patient to write a short sentence Ask the patient to copy the diagram below, e.g two 5 sided shapes that intersect to create a 4 sided figure Scoring Score 1 point for each Total of 5 1 point for each Total of 5 1 point for each Score first attempt only. Total of 3 Count the number of letters to first mistake, eg, DLORW counts 2. Total 5 1 point for each Total of 3 1 point for each Total 2 1 point 1 point for each Total 3 1 point 1 point for a complete sentence 1 point Maximum Score 30 (Cut off is below 25) Reference: Folstein, M., Folstein, S., McHugh, P. (1975). `Mini Mental State’ practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res., 12: 189-198. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 15 of 21 APPENDIX III: ABBREVIATED MENTAL TEST SCORE (AMT)21. A score of less than 8/10 is abnormal 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Age Time (to nearest hour) Address for recall at end of test (42 West St – need to recall all to gain point) Year Name of hospital/place Recognition of 2 persons (eg doctor, nurse) Date of Birth Year of 1st World War Name of present monarch Count backwards 20-1 (this tests attention) Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 16 of 21 APPENDIX IV: – SOME OF THE DRUGS / GROUPS THAT MAY PRECIPITATE DELIRIUM (THIS LIST IS NOT EXHAUSTIVE) • • • • • • • • • • • Benzodiazepines eg lorazepam Analgesics such as codeine, tramadol and other opiates Dopamine agonists eg ropinirole Anticonvulsants eg carbamazepine Antidepressants eg amitryptilline Diuretics eg furosemide Anti-arrhytmics eg digoxin Corticosteroids eg prednisolone Oxybutinin Lithium Methyldopa Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 17 of 21 APPENDIX V: DELIRIUM AUDIT TOOL To be completed on any patients that are admitted to hospital with a new diagnosis of confusion or increase confusion Male Female Age 1. What was the patient’s length of stay? (Number of days) 2. Where were they admitted from? Own Home Rest home Nursing home Other, please state 3. What was the discharge destination? Own home Rest Home Nursing home Other, please state 4. Is there evidence of cognitive testing on admission Yes No 5. Is an MMSE or AMT completed on admission Yes No 6. Is pre admission state documented Yes No 7. Is a cognitive test repeated during the patients stay Yes No 8. Is there evidence of a physical examination Yes No 9. Is there evidence of a clear history within 48 hrs This Yes No should include considerations of the following factors:Full drug history Sensory impairments Alcohol history Bowel habits Drug History Previous intellectual function (e.g. ability to manage household affairs) Functional status (e.g. actives of daily living) Onset and course of confusion Previous episodes of acute or chronic confusion Symptoms suggestive of underlying cause (e.g. infection) 11. Is there adequate assessment of causes:Yes No Full blood count including C Reactive Protein Urea and electrolytes, Calcium, blood cultures Glucose Chest X-ray ECG Pulse oximetry Urinalysis Liver function tests Thyroid function tests 12. Has emergency IM sedation been used Yes No 13 Is there a clear medical treatment plan Yes No 14 Is there evidence of evaluation of this treatment plan Yes No 15 Is there an absence of labelling words Yes No 16 Is there evidence of psychological care planning Yes No 17 Is there evidence of person centred care Yes No 18 Is there evidence of discussion with family / friends re patients condition 19 Did the patient experience any non clinical ward moves Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 18 of 21 APPENDIX VI: Delirium information for patients and relatives – Adapted from the Royal College of Psychiatrists36 About this leaflet You may find this leaflet useful if : You have experienced delirium You know someone with delirium You are looking after someone with delirium What is delirium? Delirium is a state of mental confusion. It is also known as an ‘acute confusional state’. It often starts suddenly, but usually lifts when the condition causing it gets better. It can be frightening – not only for the person who is unwell, but also for those around him or her. What is it like to have delirium? You may: Be less aware of what is going on around you Be unsure where you are or what you are doing there Be unable to follow a conversation or to speak clearly Have vivid dreams which are often frightening and may carry on when you wake up Hear noises or voices when there is nothing or no-one to cause them See people or things which aren’t there Worry that other people are trying to harm you Be very agitated or restless, unable to sit still and wandering about Be very slow or sleepy Sleep during the day but wake up at night Have moods that change quickly. You can be frightened, anxious, depressed or irritable Be more confused at some times than at others, often in the evening or at night How common is it? Up to one in three hospital patients have a period of delirium. Delirium is more common in people who: Are older Have memory problems, poor hearing or eyesight Have recently had surgery Have a terminal illness Have an illness of the brain such as an infection, a stroke or a head injury Why does it happen? Many conditions and circumstances can cause or contribute to delirium Being in an unfamiliar place Infections Having a high body temperature Constipation Side effects of drugs like pain killers or steroids Chemical problems in the body such as dehydration or low salt levels Liver or kidney problems Suddenly stopping drugs or alcohol Major surgery Brain injury (such as stroke), epilepsy Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 19 of 21 Terminal illness There is often more than one cause and sometimes the cause is not found. How is delirium treated? If someone suddenly becomes confused, they need to see a doctor urgently. The person with delirium may be too confused to describe what has happened to them so it’s important that the doctor can talk to someone that knows the patient well. To treat delirium you need to treat the cause, for example an infection may be treated with antibiotics. Can sedative medication (tranquilisers) help? Not everyone with delirium will need sedatives but they may be needed in the following situations: To calm someone enough to have investigations or treatment To stop someone endangering themselves or other people When someone is very agitated, anxious or distressed as a result of delirium When someone who drinks a lot of alcohol stops suddenly they may need a regular dose of a sedative medication that is reduced over several days. This will help with withdrawal symptoms but should be done under close medical supervision. Sometimes sedatives may make delirium worse and this will be monitored by the medical and nursing team How can I help someone with delirium? You can help someone with delirium feel more calmer and in control if you: Stay calm Talk to them in short simple sentences Check they have understood you. Repeat things if necessary Try not to agree with any unusual or incorrect ideas but tactfully disagree or change the subject Reassure them Remind them of what is happening and how they are doing Remind them of the time and date Make sure that they can see a clock or calendar Try to make sure that someone they know well is with them. This is often important during the evening when confusion often gets worse If they are in hospital bring in some familiar objects from home Make sure they have their glasses and hearing aids Help them to eat and drink Have a light on at night so that they can see where they are if they wake up How long does it take to get better? Delirium gets better when the cause is treated. You can recover very quickly but it can take several days or weeks and some may not completely recover. People with dementia can take a particularly long time to get over delirium. How do you feel afterwards? You may not remember what has happened particularly if you have had memory problems beforehand. However you may be left with unpleasant and frightening memories and even worry that you are going mad. It can be helpful to sit down with someone who can explain what happened. This might be a family member, a carer or your doctor. They can go through a diary of what happened each day. Most people relieved when they understand what happened and why. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 20 of 21 Will it happen again? You are more likely to have delirium again if you become medically unwell. Someone needs to keep an eye out for the warning signs that you are getting unwell again – whatever the original cause was. If they are worried they should get a doctor as soon as possible. If medical problems are treated early this can prevent delirium from happening again. APPENDIX VII: – THE CONFUSION ASSESSMENT METHOD (CAM) 37 The diagnosis of delirium requires a present or abnormal rating for criteria 1 and 2 plus either 3 or 4. The patient should have a cognitive test such as AMTS or MMSE. 1. Acute onset and fluctuating course – is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? Did this behaviour fluctuate during the past day – that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity? (Usually requires information from a family member or carers) 2. Inattention – does the patient have difficulty focusing attention – for example, are they easily distracted or do they have difficulty keeping track of what is being said? (Inattention can be detected by the digit span test or asking for the days of the week to be recited backwards) 3. Disorganised thinking – is the patient’s speech disorganised or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable switching between subjects? (Disorganised thinking and sleepiness can also be detected during conversation with the patient) 4. Altered level of consciousness – overall, would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness as alert (normal), vigilant (hyperalert), lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused), stupor (difficult to arouse), or coma (cannot be roused)? All ratings other than alert are scored as abnormal. Delirium diagnosis and management in Older People in a general hospital setting. Issue 1. 17.09.2010 15/02/2016 (Review date: July 2011) Page 21 of 21