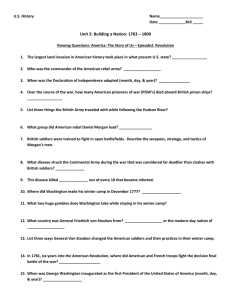

Mission Command: Genesis of a Command Philosophy

advertisement

THE ROAD TO MISSION COMMAND The Genesis of a Command Philosophy By Stephen Bungay In the course of nine hours on 14th October 1806, two Prussian armies were first shattered and then scattered by a French army at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt. In the 18th Century the Prussian Army built up by Frederick the Great had been the most admired and successful in Europe. Its defeat was militarily decisive and psychologically devastating. The Commander-in-Chief of the French forces that day has been described as ‘the most competent human being who has ever lived’1. It is well known that Napoleon Bonaparte changed the nature of warfare, the politics of Europe and the legal system of France. It is less well known, but equally important for us today, that he changed for ever the nature of organisations and how they are run, and specifically the nature of command. The French attributed the military successes they enjoyed under Napoleon to his genius, and hoped another genius would turn up to repeat them. In the wake of their defeat, the Prussians began a period of soul-searching and decided to analyse Napoleon’s methods to see what they could learn. They learned a lot. ‘We fought bravely enough,’ commented General Scharnhorst after Auerstedt, ‘but not cleverly enough.’ He championed far-reaching reforms of the Prussian Army. He was joined by Gneisenau and another colleague, Carl von Clausewitz, whose reflections on Napoleonic methods and their consequences were posthumously published in 1832 under the title ‘On War’. That work remains perhaps the most celebrated and influential military treatise ever written. The reforms of the Prussian Army were a direct consequence of the analysis carried out by Scharnhorst and the Prussian General Staff of the catastrophe it suffered at the twin battles.2 That analysis concluded that the Army had been run as a machine which required iron discipline to function because the underlying motivation of its men was low. Its training focussed on the wrong processes: it concentrated, for example, on perfecting marching drill rather than firing drill. Officers sought to counter the chaos of battle by handling troops according to mathematical principles. Nobody took any action without orders to do so. It was a highly centralised, process-dominated organisation based on Taylorian principles and assuming what Douglas McGregor has famously called the ‘Theory X’ of human motivation.3 The French Army had been raised from citizen conscripts. It had no time to practice drill and perfect discipline, so it turned this vice into a virtue. It made extensive use of light infantry or ‘tirailleurs’ who engaged the lines of Prussians in an unordered swarm in which each man took advantage of the terrain and fired as he saw fit. The French were highly motivated. Their Army was, in McGregor’s terms, a ‘Theory Y’ organisation. At the top level, Napoleon introduced mini-armies called Corps, containing a balance of 1 © Stephen Bungay 2003 infantry, cavalry and artillery, and so able to operate independently of each other. Each was commanded by a Marshal, a man picked on merit by Napoleon himself. In conducting the campaign, Napoleon was able to communicate very rapidly with the Marshals because they shared a basic operating doctrine, and he explained his intentions as well as what he wanted them to do. He expected them to use their initiative and act without orders in line with his intentions. They did. The result was an operational tempo which left the incredulous Prussians bewildered. The Prussian Army needed to get faster. It was clear that of the three classic variables in warfare - force, space and time - in modern warfare, only lost time could never be made good. It was essential to act quickly. The only way of doing so was to develop a professional officer corps with the authority and willingness to take decisions in real time at a low level. Meritocracy was a prerequisite. It was better to take a wrong decision immediately than to take no decision at all. Sins of omission were more serious than sins of commission. A Prussian officer was expected to share a set of core values, defining his ‘honour’, which took precedence over an order. If he acted in accordance with ‘honour’ (which constituted his integrity) disobedience was legitimate. It came to be recognised, moreover, that orders from above could not possibly give an officer all the direction he needed during a battle. The Commission set up in 1837 to revise the Field Service Regulations of 1788 set out a paragraph saying that if the execution of an order was rendered impossible, an officer should seek to act in line with the intention behind it.4 However, in the long peace which followed 1815, the reforms stagnated. Their spirit was kept alive by a few influential individuals. One was Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia, the nephew of the future Kaiser Wilhelm I, and a practising soldier. In a series of essays published in the 1850’s and 60’s, he reinforced the growing idea that what made the Prussian officer corps distinctive – and gave it an edge – was a willingness to show independence of mind and challenge authority.5 When Friedrich Karl replaced the octogenarian Field Marshal von Wrangel as commander of the Prussian Army in its successful war against Denmark in 1864, he was joined by a shadowy figure who had been Chief of the Prussian General Staff since 1857. Many operational commanders were not at all sure what the Chief of the General Staff was supposed to do, apart from handle administration and make sure the trains ran on time. When this Chief of Staff actually assumed command of the Prussian Army in the campaign against Austria in 1866, some of his subordinates were bemused. ‘This seems to be all in order,’ commented divisional commander General von Manstein on receiving an order from his Commander-in-Chief, ‘but who is General von Moltke?’6 Field Marshal Helmuth Carl Bernhard Graf von Moltke, a man born in the first year of his century, was the main builder of the German Army which emerged from it, and the man who established the General Staff as a body of professional soldiers pre-eminent in Europe. He was both a practitioner and thinker in the fields of strategy, leadership, organisation and what we would today call management. His thoughts are contained in numerous essays and memoranda, but his influence at the time was more direct, for he was the trainer and teacher of a generation of German generals. In that role, he could also be named as the true father of Auftragstaktik. It is perhaps his most lasting legacy. Von Moltke is known to have espoused subordinate autonomy almost to the point of abandoning central control altogether, and to have conceived of strategy as 2 © Stephen Bungay 2003 improvisation. In his appraisal of his own victory over the Austrians at Königgrätz in 1866, von Moltke observed that the independent actions of two Austrian generals, acting contrary to the orders of their commander Benedek, in fact facilitated his own victory over them. Remarkably, he exonerated them. It is easy enough to judge their actions now, he observed, but one should be extremely careful in condemning generals. In the confusion and uncertainty of war, people who exercise their own judgement run the risk of getting things wrong. That must be accepted. Fear of retribution should not curb their willingness to make those judgements. ‘Obedience is a principle,’ he memorably asserted, ‘but the man stands above the principle.’7 Von Moltke is clear about the value of independence of mind and initiative. The Prussian Army had by this time created a leadership culture within the officer corps in which this was becoming the norm, and he encouraged it. However, his ambition went further. He wanted to build on that culture and use it to create an effective system of command, one which also ensured cohesion and limited the impact of what might subsequently appear to be mistakes on the part of subordinates. In his self-critical Memoire on the 1866 campaign, written for the king in 1868, two things he singled out for particular criticism are ‘the lack of direction from above and the independent actions of the lower levels of command’.8 This may seem surprising at first, until we see where he was heading. He concluded from this that it was vital to ensure that every level understood enough of the intentions of the higher command to enable it to fulfil its goal. Von Moltke did not want to put a brake on initiative, but to steer it in the right direction. In 1869, the new Field Service Regulations, inspired and partially authored by von Moltke, made it official. Senior commanders should ‘not order more than is absolutely necessary’ but should ensure that the goal was clear. In case of doubt, subordinate commanders should seize the initiative. Meanwhile, while the French Army waited for another Napoleon it stagnated. Another Napoleon did indeed appear in the form of his nephew Louis. He assumed the title of Napoleon III, but unlike his uncle he was not a genius. When the French Army met the Prussian Army on the field again in 1870, the results of Jena-Auerstedt were reversed. A neutral observer of the campaign, the Russian General Woide, described the Prussian command doctrine as having the effect of a ‘newly perfected weapon’.9 It was indeed like a secret weapon, for it was invisible. The miracle was the way in which each man acted on his own accord, but in such a way that the actions of the army as a whole cohered. ‘Every German subordinate commander,’ wrote Woide, ‘felt himself to be part of a unified whole; in taking action, each one of them therefore had the interests of the whole at the forefront of his mind; none hesitated in deciding what to do, not a man waited to be told or even reminded.’10 The Prussian Army seemed to a remarkable degree to have mastered the fast-moving, ever-changing chaos which distinguished the modern battlefield. It appeared to have reconciled autonomy and alignment. That was not how things felt from the inside. It had won the war with France, but things had not gone smoothly. It coped better with the mess and confusion of war than its opponent had, but many of its own people were critical. After 1871, the victorious Army got into a furious argument with itself. Along with questions of tactics, the central issue under debate was how to retain control 3 © Stephen Bungay 2003 while encouraging independent action. Technology was making the issue more acute. In 1870, the Prussian infantry faced accurate fire from the French Chassepot rifles when still way beyond the range of their own needle guns, which had themselves, rendered muzzle loaders obsolete just a few years before. It marked a step in the ‘transformation of the infantry’ which meant that formations had to be loose. Control was rendered yet more difficult. Battles were often won or lost by the actions of company commanders. Sometimes they made up for mistakes committed by their superiors. Sometimes, though, their headstrong decisions led to unnecessary losses. Cohesion was on a knife-edge. Two ideas fomented the debate: the reinforcement of von Moltke’s observation that a higher intent had to unify action; and the realisation that every unit had to have a task or mission of its own to perform which made sense within that context.11 One incident in particular became a cause célèbre. On 14th August 1870, the Prussian First Army under Lieutenant General von Steinmetz approached the fortress of Metz. Just in front of it, near the town of Colombey, in accordance with von Moltke’s orders, it waited until the Second Army could reinforce it before investing the city. The commander of 26th Infantry Brigade, Major General von der Goltz, observed the French forces in front of him starting to withdraw. If the whole French army were to do so, Metz would not have to be subjected to a costly and lengthy siege, but could be by-passed, which is what von Moltke really wanted to do. There was no time for von der Goltz to ask his division, division to ask Corps, Corps to ask von Steinmetz and maybe even von Steinmetz to ask von Moltke what to do, and then relay the order back again. So von der Goltz attacked. His men got into trouble, but his neighbouring brigadier saw what was happening and joined in. So then did the two divisions of I Corps, against an express order to remain on the defensive. Von Steinmetz was furious with the lot of them, and ordered them to withdraw, so they sent back a few of their reserve troops to placate him. In the morning the King arrived and forbade any retreat, for now the French were retreating. Metz was indeed by-passed. Von der Goltz was accused of recklessness. The debate over his case continued for decades in numerous publications. The final judgement was passed in a tactical manual published in 1910: ‘His decision is one of the finest examples of spontaneous action taken within proper bounds.’12 Passing final judgement on tactical methods took almost as long. The argument started as a three-way contest. The first group were the conservatives who saw themselves as the upholders of the true Prussian tradition. They wanted to abandon the curse of loose-order tactics which allowed the battlefield to descend into chaos and re-establish disciplined close-order formations. Their voices soon melted away.13 The main debate was conducted by two schools, both demanding change. One, known as Normaltaktiker, wanted to establish coherence by training infantry leaders in the use of detailed tactical norms which specified methods of deployment and attack. The other school, the Auftragstaktiker, argued that no such recipes were possible. Tactical decisions should be left to junior leaders on the spot. Anything else would drive out the spirit of initiative. Junior leaders had to be trusted to make the right decisions. The Army had to learn to live with and exploit chaos, not seek to control it.14 The Auftragstaktiker of the Prussian Army, which after 1871 became the German Army, were developing a new concept of discipline. Discipline did not mean following orders but acting in accordance with intentions. The phrase ‘thinking obedience’ begins to 4 © Stephen Bungay 2003 appear. Distinctions were made between an ‘order’ (‘Befehl’) and a ‘task’ or ‘mission’ (‘Auftrag’). People started to talk about ‘directives’ (‘Weisungen’) as an alternative to orders. In 1877, General Meckel wrote that a directive had two parts. The first was a description of the general situation and the commander’s overall intention. The second was the specific task. Meckel stressed the need for clarity: ‘Experience suggests,’ he wrote, ‘that every order which can be misunderstood will be.’15 The intention should convey absolute clarity of purpose by focussing on the essentials and leaving out everything else. The task should not be specified in too much detail. Above all, the senior commander was not to tell his subordinate how he was to accomplish his task, as he would if were to issue an order. The first part of the directive was to give the subordinate freedom to act within the boundaries set by the overall intention. The intention was binding. The task was not. A German officer’s prime duty was to reason why. The debate peaked in the formulation of the new Field Service Regulations, the Exerziersreglement of 1888. It recognised that battle quickly becomes chaotic. It emphasised independence of thought and action, stating that ‘a failure to act or a delay are a more serious fault than making a mistake in the choice of means’. Every unit was to have its own clearly defined area of responsibility, and the freedom of unit commanders extended to a choice form as well as means, which depended on specific circumstances. The responsibility of every officer was to exploit their given situation to the benefit of the whole. The guiding principle of action was to be the intent of the higher commander. Officers were to ask themselves the question: ‘What would my superior order me to do if he were in my position and knew what I know?’ An understanding of intent was the sine qua non of independent action.16 It was clear that if individuals within the organisation were to tread along the narrow path between the Scylla of rule-book passivity and the Charybdis of random adventurism, and so unify autonomy and alignment, their selection and training were important. They had to be ready to make decisions and to accept responsibility for them. They must also have a shared understanding of how to behave and what they could expect of their peers and their superiors. They needed a common operational doctrine and shared values. The organisation had to have a high level of trust. Training was directed to these ends. The Auftragstaktiker had won through. But their opponents did not give up. The new regulations were subject to continual criticism in journals, and it is there in fact that the term Auftragstaktik is first found in the early 1890’s, coined by its opponents.17 The first attempt to define it in writing did not come until 1906, when Major Otto von Moser published a widely read but unofficial book about small unit tactics which devoted five pages to the concept. Von Moser emphasised its value as a means of reconciling independence and control.18 The arguments continued into the first decade of the 20th Century, which saw two events which finally drew the debate to a close. The first was the Boer War of 1899-1902, the second the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. Both were taken to illustrate the superiority of the new doctrine as mirrored in the tactics of the Boers in the one case and of the Japanese in the other. The Japanese had indeed adopted the principles of the 1888 Regulations. The new German Regulations of 1906 confirmed them.19 In 1914, the methods which had overcome the French in 1870 served to overcome the 5 © Stephen Bungay 2003 Russians at Tannenberg, but narrowly failed in the west. As the front became static, the principles of Auftragstaktik played a secondary role to principles of attrition, and so the First World War took its dreadful course until 1918. Even so, Auftragstaktik played its part in enabling the Germans to hold their lines against successive Allied offensives. In an environment in which communications between higher commanders and junior officers were uniquely fragile, the speed with which junior officers reacted to potential breakthroughs was critical to maintaining an effective defence. The willingness of German company commanders to change dispositions, commandeer reserves and launch local counter-attacks without further orders was one factor among many why so many Allied offensives stagnated.20 In March 1918, for the first time since late 1914, the German Army abandoned its reliance on artillery, machine guns and trenches and flung a body of infantrymen called ‘Stormtroopers’ who were imbued with the principles of Auftragstaktik at the British lines. They made the largest gains in territory ever achieved on the Western Front and were only slowed and finally halted by the resilience and firepower of their opponents, ordered by Haig to fight ‘with their backs to the wall’. On 18th July, the British counter-attacked, and having themselves achieved a skill and flexibility in the use of artillery unique at the time, joined their Allies to force them back until on 11th November, they signed an armistice. The 100,000 men the Allies allowed the Germans to keep as an army reexamined their 100-year-old traditions. The new German General Staff realised that in any future war of attrition they would always be overwhelmed in the end. There were several schools of thought. One was to defend Germany with a series of fortresses; another was to adopt guerrilla methods. The one which prevailed was to achieve rapid decision on the battlefield and use superior speed and manoeuvrability to compensate for lack of overall numbers.21 The lessons of the failed offensive of March 1918 were examined in detail. There had been no clear aim, the Army had out-run its logistical capability and its Stormtroopers had been left without proper artillery support. The answer was to mechanise the part of the Army tasked with achieving breakthrough, and provide it with mobile artillery. Thinking which at first revolved around armoured cars eventually embraced the medium tank as the best potential solution. Achieving breakthrough meant focussing energy at a decisive point, and in thinking which went back to Clausewitz and Napoleon, the concept of a Schwerpunkt, or ‘centre of gravity’ became central to a doctrine the world now recognises as ‘Blitzkrieg’. It would be impossible to realise this notion of manoeuvre warfare without a command and control system which had Auftragstaktik as its core. Speed became a weapon in itself, the psychology of the enemy commander as important a target as the forces he commanded. The objective now was not just to master a rapidly changing situation but to actually make the situation change as fast as possible so as to paralyse the enemy. The command and control advantages of Auftragstaktik were therefore put to operational use. Superiority in command capability had become part of the German Army’s arsenal. It had truly become a secret weapon. With an Army of 100,000 men, the Chief of the General Staff, Hans von Seeckt, a veteran of the mobile war in the East, decided to turn it into an Army of 100,000 officers. Training was centred on inculcating initiative and ‘thinking obedience’. To further this and create greater levels of trust, all NCO’s were trained as officers and officers were 6 © Stephen Bungay 2003 expected to master the tasks of two ranks higher up the hierarchy and to take their place if needs be. In 1933, the German Army produced a new guide to its leadership philosophy called ‘Truppenführung’ (literally ‘Troop Leadership’). The British Army’s equivalent was called ‘Field Service Regulations’. The titles alone point to a significant difference in mind-set. Like the German Army, the British Army had concluded that the battlefield was inherently chaotic. Rather than thriving on the chaos, the British sought to control it through a ‘masterplan’. The masterplan specified in great detail precisely what everyone was to do and how they were to do it. British training stressed obedience, and drill was used to inculcate its spirit. Initiative was effectively equated with insubordination. Being of a liberal disposition, however, the British did not impose a tactical doctrine. The result of that was that no-one at lower levels knew what anyone else was likely to do under any given set of circumstances. The British also allowed senior officers the freedom to interpret orders. The result of that was that high-level orders became debating topics. The debates would go on as the battle raged, and decision-making and action were very slow. Junior officers, on the other hand, were only allowed to depart from orders if circumstances changed so as to render them irrelevant. If they wished to do so, they had to seek permission from a higher authority before doing so, as opposed to informing their superiors about what they were going to do and getting on with it. So they were very slow as well.22 It was a low-trust doctrine. The 1933 Truppenführung marks the next stage in the maturity of Auftragstaktik. In accordance with Clausewitz, it accepts complexity, uncertainty, rapid change and stress as the battlefield norm. It defines the qualities demanded of an officer. ‘Next to a knowledge of men and a sense of justice’, it states, ‘he must be distinguished by a superiority of knowledge and experience.’23 In other words, leaders had to demonstrate social competence, integrity and task competence. British officers were expected to manage battles. German officers were expected to lead their men. The German command and control system had reached a new level of refinement. ‘The basis of leadership’, we read, ‘is to be found in the task (Auftrag) and the situation. They must constantly be held in view. A task including many objectives is always difficult to keep in mind. Uncertainty of the situation is the rule. Seldom will more accurate information be available. To clear up the situation is an obvious requirement. Waiting for information in strained situations is seldom an indication of good leadership however, and usually a grievous shortcoming.’ ‘From the task and the situation springs the plan. Where the plan no longer corresponds to the situation, or if it is obviated by events, so must the plan take these facts into consideration. Where anyone alters a task or does not carry it out he must report it, and he alone must be responsible for the consequences. He must always operate in the framework of the whole…The plan must be made against a clear objective with all the means available…In the changing fortunes of war, however, to hold stubbornly to a decision regardless of the situation may amount to a fault…A commander must give his subordinates a free hand in execution so far as it does not endanger his objective. He must not however pass on the responsibility for decisions which rightly should rest with him.’24 At 6am on 1st September 1939, Hitler unleashed the organisation built around these 7 © Stephen Bungay 2003 principles on Poland, and on 5th October the last fragment of the Polish Army surrendered. On 10th May 1940, he unleashed it on France and on 22nd June France surrendered, the British Army having in the meantime been evacuated from Dunkirk. On 22nd June 1941 he unleashed it on the Soviet Union, and it proceeded to gain the largest and most spectacular victories in the history of land warfare. In the end, of course, despite all the battles won by the German Army, Germany lost the war. However, it took the combined forces of the two post-war superpowers, the British Empire and the resistance of most of western Europe five years to defeat it. The war became a war of attrition like the previous one, and Hitler’s hideous ideology gathered against him an alliance wielding massive superiority of resources. Despite that, in its last battle, the Battle of Berlin in April-May 1945, what remained of the German Army inflicted 300,000 casualties on the three Soviet Army Groups which overcame it.25 In the historiography of the Second World War, attention has been increasingly been devoted to the performance of the German Army and what can be learned from it. It was remarkable, as any of those who fought against it will attest. As one American veteran of Normandy and the Rhineland puts it: ‘until you’ve fought the German army, you have never fought a real battle’.26 Scholars and researchers tried to analyse why this was so. In 1977 US Army Colonel Trevor Dupuy concluded: ‘On a man for man basis, the German ground soldier consistently inflicted casualties at about a 50% higher rate than they incurred from the opposing British and American troops under all circumstances. This was true when they were attacking and when they were defending, when they had a local numerical superiority and when, as was usually the case, they were outnumbered, when they had air superiority and when they did not, when they won and when they lost.’27 The reasons for this are many and various, but there can be little doubt that one of the major ones was Auftragstaktik.28 A contributing factor to the German defeat was Hitler’s contempt for its principles and his attempts to reverse its practice, particularly on the Eastern Front from 1942 onwards. Running through the whole conception is the principle of trust. Hitler had never trusted his generals, and as his mistrust grew, so did his interference and the level of detail he tried to manage.29 Despite this, the main body of the Army continued to use Auftragstaktik. After a while some of those who defeated the German Army began to realise that the Germans were on to something and began to devote the subject some attention. As it crossed both the Channel and the Atlantic, so Auftragstaktik slipped into English as ‘mission command’.30 If it is perilous to search for universal truths about leadership, then the hazards of seeking universal principles behind what makes effective organisations are at least as great. Yet the rewards of identifying some things which at the very least are very important most of the time could also be great. Indeed, to positively deny that there could be any such things seems to fly in the face of evidence. In the first book ever devoted specifically to the nature of command, one of the world’s leading military historians summarised his findings as follows: ‘The fact that, historically speaking, those armies have been most successful which did not turn their troops into automatons, did not attempt to control everything from the top, and allowed their subordinate commanders considerable latitude has been abundantly demonstrated. The Roman centurions and military 8 © Stephen Bungay 2003 tribunes; Napoleon’s marshals; Moltke’s army commanders; Ludendorff’s storm detachments; Gavish’s divisional commanders in 1967 – all these are examples, each within its own stage of technological development, of the way things were done in some of the most successful military forces ever.’ He goes on to cite the principles of sacrificing certainty for speed, specifying minimum objectives, granting freedom of action to junior officers on the spot and hands-off headquarters as ‘indispensable elements of what the Germans, following the tradition of Scharnhorst and Moltke, call Auftragstaktik, or mission-oriented command system.’ He concludes by showing how all these principles can be found in all the outstanding examples he cites and that all successful command systems reconcile autonomy and alignment.31 With great consistency, mission command allows an organisation to make rapid decisions in an uncertain, fast-changing environment and to translate them, without delay, into decisive action. Such an organisation can act faster than its opponents and keep on doing so, because speed is built into it structurally. By the same token, it can exploit unexpected opportunities and recover from setbacks. Mission command creates an organisation which is not only more thrusting, but more resilient. If they have a clear understanding of purpose, people understand what matters and can react fast to whatever is unexpected, be it good or bad. In war, the unexpected is normal, and it is often unpleasant. Beyond this, mission command unleashes human energy and acts a motivator. It demands, creates and fosters large numbers of leaders and enables them to stretch themselves whilst working within limits. None of this is theory or supposition. It is a set of practices with a couple of centuries experience behind it. If van Creveld is right, the experience base goes back a couple of millennia, though some parts of it are more accessible than others. The recent experience of the German Army is very accessible but for some time after the war nobody bothered to examine it. After all, what did the winners have to learn from the losers? With the formation of NATO, the losers became allies, but very junior ones. It was in any case beginning to look as if technology would allow masterplanners to control everything as perfect information became instantaneously available at the centre. As the brightest and the best assembled in Washington to run the Vietnam War under former Ford executive Robert McNamara, they revelled in vast amounts of data and superb communications. They measured bodycounts and then told the Generals in Vietnam what to do next. It created a ‘pathology of information’. 32 The business paradigms and management theory of the 1960s invaded the Pentagon and it all went horribly wrong. The impact of Vietnam on the US military bears some comparison with the impact of Jena on the Prussians. Digesting those lessons continued over a long period until, with the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s, the whole of NATO went through an identity crisis. NATO had been designed to fight the Red Army as it swarmed over the North German plain. There was a masterplan. Every NATO soldier knew exactly where he had to go and what he had to do when that happened. When it became clear that it was not going to happen, NATO had to prepare for something else, the nature of which no one could specify. Traditional methods of command and control clearly had to be replaced. The answer was mission command. 9 © Stephen Bungay 2003 In the British Army, the ground had already been prepared in the 1980’s by Field Marshal Sir Nigel Bagnall. He first introduced manoeuvrist doctrine when commander of 1st Corps in Germany. As commander of Northern Army Group from 1983 he argued that NATO’s ‘tripwire’ approach was an inadequate counter to current Soviet doctrine and his influence spread beyond the British Army to other NATO forces. From 1985-88 he was Chief of the General Staff. As such, he was to ‘mission command’ what von Moltke was to Auftragstaktik. Today, the operational manuals of organisations like the US Marine Corps or the British Army all contain passages which could have been lifted from Truppenführung. Mission command is part of official NATO doctrine. Something like it, though not necessarily with the same name, has long been practiced by élite forces. NATO has realised that something like it was not just a burdensome necessity given the flexibility it suddenly had to have, but actually turned regular army units into high performance organisations. It was first applied on a large scale in the Gulf War of 1991. It has been used on peacekeeping and security operations such as Operation ‘Palliser’ in Sierra Leone in 2000. It was last put to the test in Iraq in 2003. The techniques of mission command, such as the estimate process, continue to be refined. It affects recruiting, training, planning and control processes and how operations are conducted. But its core is the culture and values of an organisation and a specific philosophy of leadership. It crucially depends on factors which do not appear on the balance sheet of an organisation: the willingness of officers to accept responsibility; the readiness of their superiors to back up their decisions; the tolerance of mistakes made in good faith. Designed for an external environment which is unpredictable and hostile, it builds on an internal environment which predictable and supportive. At its heart is a network of trust binding people together up, down and across a hierarchy. Achieving and maintaining that requires constant work. It is under test every hour of every day. Mission command is a conception of command which unsentimentally places human beings at its centre. It does so because the most sophisticatedly over-engineered product of natural selection, the human mind, is still the best instrument for maintaining rationality in chaotic conditions. The main threat to mission command is the belief that technology will render it redundant by allowing command to be supplanted by control. Centres are always data-hungry. They tend to aspire to omniscience. Their secret desire is omnipotence, which is just a step behind. History suggests, circumstantially but firmly, that these are dangerous illusions. Technology should be the servant of doctrine. A Roman centurion of the 1st Century BC was animated by independence of mind, a sense of responsibility and commitment to achieving a collective goal. A British officer of the 21st Century AD faces greater unpredictability and needs even greater creativity to deal with it. He will need just the same qualities in even greater measure. Mission command grants him a framework within which he can develop them. The rest is up to him. The man stands above the principle. Dr Stephen Bungay is a writer, business teacher and management consultant. A Director of the Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, and former Vice President of The Boston Consulting 10 © Stephen Bungay 2003 Group, he is the author of The Most Dangerous Enemy, Aurum Press 2000, which one reviewer has called ‘the most exhaustive and detailed account of the Battle of Britain that has yet appeared’ and Alamein, Aurum Press 2002. He is currently working on a book on mission command and its value to business. 1 Martin van Creveld, Command in War, Harvard University Press 1985, p. 64. On what follows see Dirk Oetting’s superb Auftragstaktik – Geschichte und Gegenwart einer Führungskonzeption, Report Verlag 1993. All translations are the author’s. 3 Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprise, Penguin 1987 (first published by McGrawHill 1960). As an organisation, the Prussian Army which came to grief in 1806 was strikingly similar to many large western business corporations 150 years later. 4 Oetting, pp. 86-8. 5 Oetting, pp. 97-103. 6 Michael Howard, The Franco-Prussian War, Rupert Hart-Davis 1961, pp. 27-29. 7 Oetting, p. 112. 8 Oetting, p. 105. 9 Oetting, p. 13. 10 Oetting, p. 116. 11 Stephan Leistenschneider, Auftragstaktik im preußisch-deutschen Heer 1871 bis 1914, Mittler Verlag 2002, pp. 46-55. 12 Oetting p. 126. For an account of the incident see pp. 113-4 and more broadly the one in Michael Howard’s classic work, op.cit., pp. 139-144. Though tactically a French victory, the strategic consequences were to impose a vital delay on the French. Howard tellingly observes that ‘no officer in the French Army had, or was supposed to have, any insight into the intentions of the commander-in-chief’ (p. 145). It marched blindly to disaster. 13 Though they themselves and their followers presumably did not, as some German units employed these methods, with predictable results, in 1914. 14 Leistenschneider, op. cit., pp. 65-67. 15 Oetting p. 125. 16 Leistenschneider, op. cit., pp. 72-92. 17 Leistenschneider, op. cit., pp. 100-106. It was not officially defined until 1977. See Oetting p. 14. 18 Oetting, pp. 16-19. 19 Leistenschneider, op. cit., pp.123-137. 20 For an example of this see Martin Samuels’ analysis of the German defence of Thiepval and the Schwaben Redoubt on the Somme in Command or Control – Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies 1888-1918, Frank Cass 1995, pp. 149-157. The communications problem faced by the attackers was more severe still than that of the defenders. See Gary Sheffield, Forgotten Victory, Headline 2001, pp. 120-123. The inherent balance of advantage was nevertheless compounded by each side’s approach to command and control, and doctrine. 21 See James S. Corum, The Roots of Blitzkrieg – Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform, University Press of Kansas, 1992, pp. 55-66. 22 See David French, Raising Churchill’s Army, OUP 2000, pp. 17-59. 23 Truppenführung, PRO WO 287/124, § 7. Its main author was Ludwig Beck, who became Commander-in-Chief of the German Army and later organised the bomb plot against Hitler. It may be worth observing that the German Army, the main instrument of his destructive will, was the only institution in the Nazi state to offer organised resistance to Hitler. The legal system did not, industry did not, the universities did not, nor did the Protestant or the Catholic Church. Hitler mistrusted the Army from the first and sought gradually to replace it with the Waffen-SS. It may be that whilst most German generals accepted their personal oath of loyalty to Hitler as absolute and became his willing executioners in the East, the old concept of ‘honour’ implied by von Moltke’s words ‘Obedience is a principle, but the man stands above the principle’ continued to echo in the souls of a few men like Beck, von Stauffenberg and their co-conspirators in the 2 11 © Stephen Bungay 2003 General Staff. Their notion of honour would have sat easy with Enlightenment thinkers like Lessing. The motto of the Waffen-SS was ‘Loyalty is my Honour’ (‘Meine Ehre heißt Treue’), which would have been endorsed by the Nibelungen. 24 Truppenführung, §§ 36-7. 25 John Erickson, The Road to Berlin, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1983, p. 622. 26 Belton E. Cooper, Death Traps, Presidio Press 1998, p. 242. 27 Colonel Trevor Dupuy, A Genius for War, Macdonald & Janes 1977, pp. 253-4. Dupuy bases his claims on an analysis of data from actual engagements in North Africa, Italy and North West Europe. This analysis has predictably been challenged, in particular its methodology, but the broad conclusions are generally accepted. See David French, Raising Churchill’s Army, OUP 2000, pp. 8-10. 28 As argued by Martin van Creveld in his Fighting Power, Greenwood Press 1982. 29 Hitler’s perversion of the Army’s leadership philosophy is charted by Oberstleutnant Dr HansPeter Stein in ‘Führen durch Auftrag’, Truppenpraxis, Beiheft 1/85. 30 Some have followed Richard Simpkin in preferring the term ‘directive control’. Simpkin ably argues his case for rejecting the rendering ‘mission command’ as ‘disastrous’ in Race to the Swift, Brassey 1985, pp. 227-240. He seems nevertheless to have lost the battle over terminology. 31 Martin van Creveld, Command in War, Harvard University Press 1985, p. 270. 32 Van Creveld, pp. 258-60 12 © Stephen Bungay 2003