Trauma and Resuscitation MCQs

advertisement

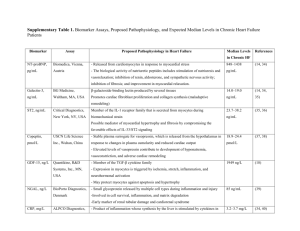

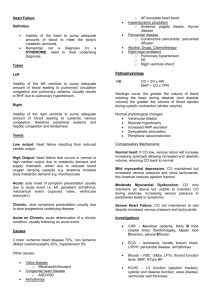

TRAUMA & RESUSCITATION (http://stgan.com/mcqmain.asp) The recommended dose of vasopressin for the treatment of refractory pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF) is: (15) A. 10 IU. B. 20 IU. C. 40 IU. D. 80 IU. E. 160 IU. Ans: C Vasopressin is emerging as an important 'new' drug for the treatment of refractory VT or VF. - In their current guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, the American Heart Association and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation have made major changes to the recommendations for advanced cardiovascular life support. One of these changes is that a single 40IU dose of intravenous vasopressin can be used as an alternative to adrenaline for the management of ventricular fibrillation /pulseless VT. This change is based on limited but reasonably persuasive evidence that vasopressin is an effective vasoconstrictor and has a good safety profile; it is unlikely to cause beta stimulation and or postarrest adrenergic storm. However, adrenaline also remains acceptable. See: Forrest P. Vasopressin and shock.Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001 Oct;29(5):463-72. The American Heart Association and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. An international consensus on science. Circulation. 2000;102(suppl 1):1-384. A 70 kg adult is persistently hypotensive following recent coronary artery grafting. The systemic vascular resistance has been measured and been found to be extremely low. Current therapy includes the use of high dose noradrenaline. The decision is made to switch the vasopressor to vasopressin. Used in these circumstances: (9) 1. An appropriate initial dose rate for infusion of the drug would be 0.1 IU/minute. 2. The drug is likely to have potent anti-diuretic effects. 3. The drug is unlikely to cause arrhythmias. 4. The drug is likely to cause hyperglycaemia. Ans: 1,3 Forrest has recently written an excellent, comprehensive review of the role of vasopressin in the treatment of shock. According to this author: " The vasopressin doses typically used post CPB were </= minute.? In contrast to DDAVP, the drug is not likely to have potent anti-diuretic effects when used in this way. Again, according to Forrest: "The antidiuretic properties of vasopressin result from an increase in the capillary permeability of the distal tubule and collecting duct of the nephron. The vasopressin analogue desmopressin (DDAVP) is primarily a V-2 agonist, with only 0.05% of the pressor activity of arginine vasopressin. Although vasopressin is antidiuretic, it has been shown to increase urine output during haemorrhage, sepsis` and severe heart failure. Possible explanations are that vasopressin may increase renal perfusion pressure secondary to increased systemic pressure and it may also increase glomerular filtration rate by selectively constricting the glomerular efferent arteriole. Finally, renal sympathetic innervation is also involved in the modulation of the renal vascular response to vasopressin. In response to renal denervation, vasopressin produces a marked constrictor response." The absence of major side-effects of the drug has been commented on by many authors. In particular, cardiac arrhythmias have rarely been reported when the drug is used in the circumstances described above. The drug does not interfere with glucose metabolism. See: Forrest P. Vasopressin and shock.Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001 Oct;29(5):463-72. The best single indicator of the severity of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning is: (129) A. Alveolar:arterial oxygen tension difference. B. Mixed venous PO2. C. Arterial base deficit. D. Carboxyhaemoglobin level. E. Arterial PCO2. Ans: C There is no really satisfactory measure of the severity of CO poisoning. COHb levels do not correlate particulalry well - possibly because, under some circumstances, the half-life of COHb breathing 100% oxygen at 1 atmosphere can be as short as 30 minutes. Turner et al have recently concluded that "that initial acidosis is a better predictor of treatment requirements and severity than initial COHb." See: J Accid Emerg Med 1999 Mar;16(2):96-8: Carbon monoxide poisoning treated with hyperbaric oxygen: metabolic acidosis as a predictor of treatment requirements. Turner M, Esaw M, Clark RJ. The Australian Resuscitation Council recommendation for an initial shock in an adult patient with ventricular fibrillation is: (465) A. 25 Joules B. 50 Joules C. 100 Joules D. 200 Joules E. 360 Joules Ans: D 200 Joules In patients who are successfully resuscitated from ventricular fibrillation, the proportion who require 3 shocks or less is approximately: (466) A. 30% B. 40% C. 60% D. 80% E. 90% Ans: D 80% BMJ 1991 Jun 22;302(6791):1517-20 "Heartstart Scotland"--initial experience of a national scheme for out of hospital defibrillation. Cobbe SM, Redmond MJ, Watson JM, Hollingworth J, Carrington DJ OBJECTIVE--To determine the outcome of out of hospital defibrillation in Scotland during the year after the introduction of automated external defibrillators in October 1988. DESIGN--Retrospective analysis of ambulance service reports and hospital records. SETTING--Scottish Ambulance Service and acute receiving hospitals throughout Scotland. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Delay from cardiac arrest to first defibrillator shock; vital state on arrival at hospital accident and emergency department; survival to hospital discharge. RESULTS--During the study period 268 defibrillators were purchased by public subscription and 96% of the 2000 ambulance crew underwent an eight hour training programme in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation. A total of 1111 cardiac arrests were recorded, and defibrillation was indicated and undertaken in 602 (54%) patients, mean age 63 (range 14-92) years. A spontaneous pulse was present on arrival at hospital in 180 (30%) of the defibrillated patients, and 75 (12.5%) were subsequently discharged alive. As expected, the likelihood of survival was inversely related to the delay from the onset of cardiac arrest to the time of the first shock and was greater in the case of witnessed arrest. If ventricular fibrillation occurred after the arrival of the ambulance, survival to discharge was 33%. CONCLUSIONS--An effective scheme for out of hospital defibrillation can be introduced rapidly, and with limited training implications and costs, by the use of automated external defibrillators in ambulances. Tunstall-Pedoe H. et al, Survey of 3765 cardiopulmonary recuscitations in British hospitals (the BRESUS study). BMJ 1992;304:1347-51. The Australian Resuscitation Council recommendation for an initial dose of amiodarone given by intravenous injection during a cardiac arrest is: (467) A. 1 mg/kg. B. 2 mg/kg. C. 3 mg/kg. D. 4 mg/kg. E. 5 mg/kg. Ans: E 5 mg/kg. A recent review of the role of amiodarone has been published by Gonzalez. Intravenous amiodarone for ventricular arrhythmias: overview and clinical use. Resuscitation 1998 Oct-Nov;39(1-2):33-42 Gonzalez ER, Kannewurf BS, Ornato JP Numerous pharmacological agents with varying cellular electrophysiological effects are available to treat cardiac arrhythmias. Amiodarone is predominantly a Vaughan Williams Class III agent, but also possesses electrophysiological characteristics of the other three Vaughan Williams classes (Class I and IV and minor Class II effects). Amiodarone's primary mechanism is to prolong the cardiac action potential and repolarization time leading to an increased refractory period and reduced membrane excitability. The efficacy and tolerability of intravenous (IV) amiodarone for acute treatment of recurrent and refractory ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation has been demonstrated in clinical trials. The ARREST trial, a randomized trial comparing IV amiodarone to placebo, found a significant improvement in the proportion of patients surviving to the emergency department following out-ofhospital cardiac arrest in amiodarone-treated patients. Intravenous amiodarone is an effective antiarrhythmic agent for the acute treatment of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and represents an important treatment option for emergency anti-arrhythmic therapy for patients suffering from cardiac arrest. In a patient whose temperature has fallen to 31 degrees centigrade, the activity of clotting factors will be reduced: (469) A. Not at all B. By about 20% C. By about 50% D. By about 80% E. None of the above Ans: D Hypothermia induces marked reductions in the activity of all clotting factors. At 31 degrees, the activity of the various factors is: II - 17%. V - 22%. VII - 34%. VIII - 16%. IX - 7%. X - 20%. XI - 16%. XII - 10%. By the time temperature has fallen to 25, all factors are virtually inactive. Johnson TD, Chen Y, Reed RL: Functional equivalence of hypothermia to specific clotting factor deficiencies. J Trauma 37:413, 1994. The Glascow Coma Score of a head-injured patient who opens his eyes and withdraws his arm in response to a painful stimulus and who is groaning unintelligibly is: (503) A. 6 B. 7 C. 8 D. 9 E. 10 Ans: C ? Eye Opening: 4 Spontaneous, 3 To Voice, 2 To Pain 1 Nil Verbal Response: 5 Orientated, 4 Confused, 3 Words, 2 Groans, 1 Nil Motor Response: 6 Obeys Commands, 5 Localises Pain, 4 Withdraws from Pain, 3 Abnormal Flexion, 2 Extension, 1 Nil An unconscious man is brought into hospital suffering from methyl alcohol poisoning: (540) 1. Kussmaul's breathing could be expected to be a feature of the condition. 2. Papilloedema would be consistent with this form of intoxication. 3. His plasma bicarbonate might be very low. 4. The methyl alcohol would metabolised to acetaldehyde. Ans: 1,2,3 Early manifestations of poisoning are caused by methyl alcohol, whereas the late manifestations are due to the metabolites formaldehyde and formic acid. The late manifestations include an increased anion gap, metabolic acidosis, and retinal injury. Impairment of vision due to methyl alcohol intoxication is abrupt in onset and is characterised by large symmetric central scotomata. The lesion is in the retinal ganglion cells and their axons, which constitute the optic nerve. Papilloedema is often present. The acidosis of methyl alcohol poisoning is profound, in part because it is metabolised to formaldehyde and formic acid. A patient presents to an emergency room with a six hour history of chest pain suggestive of myocardial infarction. Which of the following tests is the most sensitive and specific predictor of myocardial necrosis? (562) A. Troponin I B. CK MB fraction C. Troponin T D. 12 lead ECG. E. Sestamibi scan. Ans: A The recent development of monoclonal antibodies to cardiac troponin I and troponin T has resulted in cardiac-specific assays which appear to be the most sensitive and specific indicators of myocardial necrosis. Troponin I appears to be slightly more precise than Troponin T. See, for example: N Engl J Med 1997 Dec 4;337(23):1648-53 Emergency room triage of patients with acute chest pain by means of rapid testing for cardiac troponin T or troponin I. Hamm CW, Goldmann BU, Heeschen C, Kreymann G, Berger J, Meinertz T BACKGROUND: Evaluation of patients with acute chest pain in emergency rooms is time-consuming and expensive, and it often results in uncertain diagnoses. We prospectively investigated the usefulness of bedside tests for the detection of cardiac troponin T and troponin I in the evaluation of patients with acute chest pain. METHODS: In 773 consecutive patients who had had acute chest pain for less than 12 hours without ST-segment elevation on their electrocardiograms, troponin T and troponin I status (positive or negative) was determined at least twice by sensitive, qualitative bedside tests based on the use of specific monoclonal antibodies. Testing was performed on arrival and four or more hours later so that one sample was taken at least six hours after the onset of pain. The troponin T results were made available to the treating physicians. RESULTS: Troponin T tests were positive in 123 patients (16 percent), and troponin I tests were positive in 171 patients (22 percent). Among 47 patients with evolving myocardial infarction, troponin T tests were positive in 44 (94 percent) and troponin I tests were positive in all 47. Among 315 patients with unstable angina, troponin T tests were positive in 70 patients (22 percent), and troponin I tests were positive in 114 patients (36 percent). During 30 days of follow-up, there were 20 deaths and 14 nonfatal myocardial infarctions. Troponin T and troponin I proved to be strong, independent predictors of cardiac events. The event rates in patients with negative tests were only 1.1 percent for troponin T and 0.3 percent for troponin I. CONCLUSIONS: Bedside tests for cardiac-specific troponins are highly sensitive for the early detection of myocardial-cell injury in acute coronary syndromes. Negative test results are associated with low risk and allow rapid and safe discharge of patients with an episode of acute chest pain from the emergency room. Myocardial perfusion imaging with technetium 99m sestamibi, will reveal a defect in most patients during the first few hours after development of a transmural infarct. However, although perfusion scanning is extremely sensitive, it cannot distinguish acute infarcts from chronic scars and thus is not appropriate for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. With regard to the use of adrenaline during cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR): (592) 1. The typical initial dose in adults is 0.5 - 1.0 mg. 2. It is occasionally useful to administer doses of up to 10 mgs in divided doses to an adult. 3. The typical initial dose in children is 10 micrograms / kg 4. Adrenaline's beta effects appear to be more important that its alpha effects during CPR. Ans: 1,2,3 During CPR, the improved perfusion as a result of epinephrine's alpha-mediated constriction is far more valuable than its beta-receptor stimulation. In fact, the beta-adrenergic effects are potentially deleterious since they increase oxygen consumption. The typical initial dose in adults is 0.5-1.0 mg, whereas that in children is 10 micrograms / kg. Unusually large doses of adrenaline may be required in beta-blocked patients, those in whom receptor down-regulation has occurred (eg asthmatics), or adults with obstructed coronary vessels. A 17 year old is admitted to a large, inner city emergency department having collapsed at a 'rave' party. On admission, he has a pulse rate of 180 bpm and a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg. Shortly after admission he goes into ventricular fibrillation which responds to treatment with a counter-shock of 300 Joules and a single dose of lignocaine. An ECG performed after this shows sinus tachycardia with occasional ventricular ectopic beats. A transthoracic echo suggests mild, global hypokinesia, but no other obvious abnormality. The most likely cause for this scenario is: (657) A. Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. B. Mitral Valve Prolapse. C. Cocaine-induced cardiac toxicity. D. Viral myocarditis. E. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Ans: C All of these options can be associated with sudden cardiac arrest. Given the context, cocaine is probably the most likely. - The subject has been recently reviewed (Richman PB, Nashed AH. The etiology of cardiac arrest in children and young adults: special considerations for ED management. Am J Emerg Med. 1999 May;17(3):264-70.). Acute doses of cocaine suppress myocardial contractility, reduce coronary calibre and coronary blood flow, induce electrical abnormalities in the heart, and in conscious patients increase heart rate and blood pressure. These effects will decrease myocardial oxygen supply and may increase demand (if heart rate and blood pressure rise). Thus, myocardial ischaemia and/or infarction may occur, the latter leading to large areas of confluent necrosis. Increased platelet aggregability may contribute to ischaemia and/or infarction. Young patients who present with acute myocardial infarction, especially without other risk factors, should be questioned regarding use of cocaine. Acute depression of LV function by cocaine may lead to the presence of a transient cardiomyopathic presentation. Chronic cocaine use can lead to the above problems as well as to acceleration of atherosclerosis. Direct toxic effects on the myocardium have been suggested, including scattered foci of myocyte necrosis (and in some but not all studies, contraction band necrosis), myocarditis, and foci of myocyte fibrosis. These abnormalities may lead to cases of cardiomyopathy. Left ventricular hypertrophy associated with chronic cocaine recently has been described. Arrhythmias and sudden death may be observed in acute or chronic use of cocaine. Miscellaneous cardiovascular abnormalities include ruptured aorta and endocarditis. Most of the cardiac toxicity with cocaine can be traced to two basic mechanisms: one is its ability to block sodium channels, leading to a local anesthetic or membrane-stabilizing effect; the second is its ability to block reuptake of catecholamines in the presynaptic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous system, resulting in increased sympathetic output and increased catecholamines. Other potential mechanisms of cocaine cardiotoxicity include a possible direct calcium effect leading to contraction of vessels and contraction bands in myocytes, hypersensitivity, and increased platelet aggregation (which may be related to increased catecholamine). The correct therapy for cocaine cardiotoxicity is not known. Calcium blockers, alpha-blockers, nitrates, and thrombolytic therapy show some promise for acute toxicity. Beta-Blockade is controversial and may worsen coronary blood flow. In patients who develop cardiomyopathy, the usual therapy for this entity is appropriate. Which of the following signs is NOT suggestive of a cervical spinal cord injury? (672) A. Flaccidity. B. Increased rectal sphincter tone. C. Diaphragmatic breathing. D. Priapism. E. Hypotension with warm extremities. Ans: B Signs of injury to the cervical spinal cord include flaccidity (particularly of the rectal sphincter), diaphragmatic breathing, priapism, and hypotension. A 20 year old female weighing about 55 kgs is admitted to an emergency department having consumed 10 g of paracetamol (acetaminophen), together with alcohol, 6 hours earlier. An urgent paracetamol level is reported as 400 micrograms/ml. With regard to this scenario: (721) 1. Gastric lavage and administration of activated charcoal is indicated. 2. Administration of N-acetylcysteine is indicated. 3. Abnormalities of liver function are likely to be present at this time. 4. Hepatotoxicity is likely to occur. Ans: 2,4 Paracetamol causes severe centrilobular hepatic necrosis when ingested in large amounts. A single dose of 10 to 15 g, occasionally less, may produce clinical evidence of liver injury. Fatal fulminant disease is usually associated with ingestion of 25 g or more. Blood levels of paracetamol correlate with the severity of hepatic injury (levels above 300 ug/ml 4 hours after ingestion are predictive of the development of severe damage, while levels below 150 ug/ml suggest that hepatic injury is highly unlikely). Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and shock are early manifestations occurring 4 to 12 hours after ingestion. The features of hepatic injury do not usually become apparent until about 24 hours after ingestion. Maximal abnormalities and hepatic failure may not be evident until 4 to 6 days after ingestion, and aminotransferase levels approaching 10,000 units are not uncommon. Paracetamol hepatotoxicity is mediated by a toxic reactive metabolite formed from the parent compound by the cytochrome P450 mixed-function oxidase system of the hepatocyte. The toxic metaboliteis believed to be N-acetylimidoquinone which is detoxified by binding to glutathione. When excessive amounts of the metabolite are formed, glutathione levels in the liver fall, and the metabolite is covalently bound to nucleophilic hepatocyte macromolecules. This process is believed to lead to hepatocyte necrosis. Hepatic injury may be potentiated by prior administration of alcohol or other drugs or by conditions that stimulate the mixed-function oxidase system. In chronic alcoholics, the toxic dose of paracetamol may be as low as 2 g. N-acetylcysteine appears to act by providing a reservoir of sulfhydryl groups to bind the toxic metabolites or by stimulating synthesis and repletion of hepatic glutathione. Therapy should be begun within 8 hours of ingestion but may be effective even if given as late as 24 to 36 hours after overdose. The Rumack-Matthew nomogram can be used in deciding whether or not administration of Nacetylcysteine is indicated. Gastric lavage and administration of activated charcoal is unlikely to be of benefit more than 1-2 hours after ingestion. In a recent review from Pittsburgh, acetaminophen toxicity was the second most common cause of acute liver failure (~20% of cases) - after viral hepatitis (~30% of cases). The Australian Resuscitation Council recommend that external cardiac compression (ECC) in neonate be carried out at a rate of: (797) A. 140 bpm. B. 120 bpm. C. 100 bpm. D. 80 bpm. E. 60 bpm. Ans: C The Australian Resuscitation Council (and the Pediatric Working Group of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation) recommend a rate of 100 bpm. The patient should be placed on a firm surface, and compression directed to the lower sternum to a depth approximating a third of the anteroposterior diameter of the chest, or at a depth of 2-3 cm and rate of 100/min for a newborn or infant; depth of 3-4 cm and rate of 100/min for a small child; depth of 4-5 cm and rate of 80-100/min for a large child. ECC for a newborn or infant can be performed with two fingers, although a better technique is to encircle the chest with both hands, compressing the sternum anteriorly with the thumbs while stabilising the vertebral column posteriorly with the fingers. The rescuer's hands must encircle the chest freely and not restrict chest expansion. ECC for a small child can be performed with the heel of one hand and, for a large child or teenager, with two hands. A cycle should be 50% chest compression and 50% relaxation. The half-life of carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb t(1/2)) in carbon monoxide (CO) poisoned patients treated with 100% oxygen at atmospheric pressure is approximately: (805) A. 10 minutes. B. 30 minutes. C. 75 minutes. D. 125 minutes. E. 250 minutes. Ans: C Weaver et al recently examined a group of 93 CO-poisoned patients and concluded that the COHb t(1/2) when treated with 100% O(2) at atmospheric pressure was 74 +/- 25 min. This was considerably shorter than the COHb t(1/2) reported in prior clinical reports (approximately 130 +/- 130 min) and was influenced only by the patient's PaO2. See: Chest 2000 Mar;117(3):801-8: Carboxyhemoglobin half-life in carbon monoxide-poisoned patients treated with 100% oxygen at atmospheric pressure. Weaver LK, Howe S, Hopkins R, Chan KJ. A similar result has also been reported by Takeuchi et al. This group also examined the effect of normocarbic hyperventilation on COHb t(1/2) and were able to show that the half-life could be reduced from 78 to 30 minutes when the technique was used. See: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000 Jun;161(6):1816-9: A simple "new" method to accelerate clearance of carbon monoxide. Takeuchi A, Vesely A, Rucker J, Sommer LZ, Tesler J, Lavine E, Slutsky AS, Maleck WH, Volgyesi G, Fedorko L, Iscoe S, Fisher JA. A young man is found unconscious in a motor vehicle. The engine is running and a hose has been connected from the exhaust pipe to the interior of the vehicle. He is brought to the emergency department by ambulance while breathing 100% oxygen. On arrival he is conscious but drowsy. An arterial blood gas analysis performed at this time shows: PaO2: 560 mm Hg PaCO2: 33.7 mm Hg pH: 7.13 BXS: -16.3 COHb: 25% Hb: 150 Gm/L Given this scenario: (806) 1. Hyperbaric therapy is definitely indicated. 2. Neuropsychiatric sequelae are unlikely to occur. 3. The COHb level suggests that the poisoning is severe. 4. The base deficit suggests that the poisoning is severe. Ans: 4 The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) in the treatment of CO poisoning appears to be controversial. Scheinkestel et al have recently concluded that "HBO therapy did not benefit, and may have worsened, the outcome." and a recent meta-analysis has also cast doubt upon the use of HBO as a means of preventing neurological sequelae. See: Med J Aust 1999 Mar 1;170(5):203-10: Hyperbaric or normobaric oxygen for acute carbon monoxide poisoning: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Scheinkestel CD, Bailey M, Myles PS, Jones K, Cooper DJ, Millar IL, Tuxen DV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD002041: Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning. Juurlink DN, Stanbrook MB, McGuigan MA. (See website) If HBO is used, it should probably be implemented as early as possible in patients with a carboxyhaemoglobin level of 40% or greater; or in those with a history of loss of consciousness, persistent neurological deficits (including coma), or cardiac abnormalities. Management should consist of two treatments separated by 24 hours. 2. The incidence of neuropsychiatric sequelae following this degree of intoxication is very high probably in the order of 30-50% who survive the insult. See: Anaesth Intensive Care 1992 Aug;20(3):311-6: A longitudinal study of 100 consecutive admissions for carbon monoxide poisoning to the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Gorman DF, Clayton D, Gilligan JE, Webb RK. Smith JS, Brandon S: Morbidity from acute carbon monoxide poisoning at three-year follow-up. Br Med J 1973;1:318-321. 3. The COHb level has been consistently found to be an unreliable indicator of the severity of intoxication. The fact that the patient has been unconcscious is of much greater significance. - It should be remembered that the decrease in the oxygen carrying capacity of blood is only one of several pathophysiological 'lesions' which develop when a person is exposed to CO. Others include: Alteration of the dissociation characteristics of oxyhaemoglobin, further decreasing oxygen delivery to the tissues; Decrease in cellular respiration by binding with cytochrome a3; Binding to myoglobin, potentially causing myocardial and skeletal muscle dysfunction. Furthermore, a significant 'reperfusion injury' probably occurs as the COHb level falls. 4. A large base deficit is certainly suggestive of severe intoxication. See, for example: J Accid Emerg Med 1999 Mar;16(2):96-8: Carbon monoxide poisoning treated with hyperbaric oxygen: metabolic acidosis as a predictor of treatment requirements. Turner M, Esaw M, Clark RJ. The most appropriate first-line anticonvulsant therapy for a known epileptic in status epilepticus is: (895) A. Diazepam 0.15 mg/kg. B. Lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg. C. Phenobarbital 5 mg/kg. D. Phenytoin 18 mg/kg. E. Thiopentone 5 mg/kg. Ans: B See the excellent review by Chapman, Smith and Hirsch. These authors make the point that "Unfortunately, there is no ideal drug and a compromise between effective therapy and its inevitable side-effects often has to be accepted. " However, of the options which are presented, Lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg is likely to be the most effective. (Note that the correct dose of phenobarbital is 15 mg/kg.) See: Chapman MG, Smith M, Hirsch NP. Status epilepticus. Anaesthesia. 2001 Jul;56(7):648-59. and: Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY et al. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine 1998; 339: 792–8 The plasma half-life of vasopressin is approximately: (922) A. 20 seconds. B. 2 minutes. C. 10 minutes. D. 20 minutes. E. 1 hour. Ans: D The plasma half-life of vasopressin has been reported to be 24 minutes. See: Baumann G, Dingman JF. Distribution, blood transport, and degradation of antidiuretic hormone in man. J Clin Invest. 1976 May;57(5):1109-16. See also, the excellent, comprehensive review of the role of vasopressin in the treatment of shock by Forrest. ( Forrest P. Vasopressin and shock.Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001 Oct;29(5):463-72.) The likelihood of the diagnosis of acute coronary ischaemia being missed by staff of the emergency department (ED) in a major metropolitan hospital is approximately: (935) A. 0.2% B. 2% C. 5% D. 10% E. 20% Ans: B Pope et al recently reviewed the records of over 10000 patients who attended the ED's in the US with presenting symptoms suggestive of acute coronary ischaemia. (Chest, left-arm, jaw, or epigastric pain or discomfort; shortness of breath; dizziness; palpitations; syncope; or other symptoms suggestive of acute ischemia. ). Of these patients, 17 percent ultimately met the criteria for acute cardiac ischaemia. Of the 889 patients with acute myocardial infarction, the rate of missed diagnosis 2.1 percent. Of the 966 patients with unstable angina, the rate of missed diagnosis was 2.3 percent. Women were at particular risk of misdiagnosis. See: Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, Woolard RH, Feldman JA, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Selker HP. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000 Apr 20;342(16):1163-70. A 70 year old man presents to an emergency department with full-thickness burns to 50% of his body In the region of the head and thorax. He has clinical evidence of an airway burns. The predicted mortality for this patient is approximately: (978) A. 10%. B. 30%. C. 50%. D. 70%. E. 90% Ans: E Ryan et al conducted a retrospective review of 1665 patients with acute burn injuries admitted from 1990 to 1994 to Massachusetts General Hospital and the Shriners Burns Institute in Boston. Using logistic-regression analysis, they developed probability estimates for the prediction of mortality based on a minimal set of well-defined variables. They identified three important risk factors for death: Age greater than 60 years; More than 40 percent of body-surface area burned; and inhalation injury. These factors predicted 0.3 percent, 3 percent, 33 percent, or approximately 90 percent mortality, depending on whether zero, one, two, or three were present. The presence of an airway burn was of particular importance in predicting mortality. See: Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, Sheridan RL, Cassem EH, Tompkins RG. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998 Feb 5;338(6):362-6. A 45 year old patient suffers a subarachnoid haemorrhage and becomes clinically brainstem dead. Tests of brainstem death are carried out in compliance with the guidelines issued by the Conference of Medical Royal Colleges of the United Kingdom Given this scenario, which of the following statements are correct? (985) 1. If an EEG is performed, there will be no activity. 2. The patient will have diabetes insipidus. 3. The patient will not develop hypertension in response to a surgical incision. 4. The oculovestibular reflexes will be absent. Ans: 4 Readers are referred to the editorial by Young and Matta in the journal 'Anaesthesia'. Although brainstem death (properly diagnosed by independent experts under appropriate conditions) is widely accepted as one of the criteria which must be fulfilled before organ donation can be undertaken, it should be understood that such patients may exhibit considerable evidence of other neurological activity. For example, Grigg et al reviewed 56 'brain dead' patients and found EEG activity in about 20% of cases. Howlett et al examined anterior and posterior pituitary function in 31 brainstem dead patients and found that diabetes insipidus was NOT present in about 25% of the patients. Wetzel et al examined the haemodynamic response to organ donation in 10 brainstem dead patients and found that systolic pressure increased by a mean of 31 torr, diastolic pressure by 16 torr, and heart rate by 23 beats/min in response to surgical stimulation. The oculovestibular reflexes MUST be absent before the diagnosis of brainstem death can be made.. See: 1. Young PJ, Matta BF. Anaesthesia for organ donation in the brainstem dead--why bother? Anaesthesia. 2000 Feb;55(2):105-6. 2. Grigg MM, Kelly MA, Celesia GG, Ghobrial MW, Ross ER. Electroencephalographic activity after brain death. Arch Neurol. 1987 Sep;44(9):948-54. 3. Howlett TA, Keogh AM, Perry L et al. Anterior and posterior pituitary function in brain-stem-dead donors: a possible role for hormone replacement therapy. Transplantation 1989; 47: 828–34. 4. Wetzel RC, Setzer N, Stiff JL et al. Hemodynamic responses in brain dead organ donor patients. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1985; 64: 125-8.