vitamin D - NHS Evidence Search

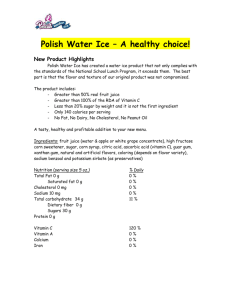

advertisement

Medicines Q&As Q&A 329.1 Which oral vitamin D dosing regimens correct deficiency in pregnancy? Prepared by UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists for NHS healthcare professionals Before using this Q&A, read the disclaimer at www.ukmi.nhs.uk/activities/medicinesQAs/default.asp Date prepared: January 2014 Summary During pregnancy, maternal vitamin D deficiency (defined here as less than 30nmol/L) can lead to deficiency in the infant, resulting in Rickets and other skeletal abnormalities. Testing: There is no consensus on exactly which pregnant women to test for vitamin D deficiency. However, if a pregnant woman is tested for deficiency and found to be deficient, then consideration should be given to correcting this deficiency. Safety: Vitamin D use in human pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformation, although the data are insufficient to confirm that there is unequivocally no risk. In the general population, an upper physiological limit of 10,000units of vitamin D/day has been suggested. Above this daily dose, adverse effects are theoretically more likely so bolus injections or oral doses of more than 10,000units per day should not be used. Dose for correction (vitamin D <30nmol/L): It would be rational to use an oral dose of 4000units per day for up to 11 weeks to provide a cumulative dose of around 300,000units in pregnancies that are in the 2nd or 3rd trimester . Correction should begin in the 2nd or 3rd trimester because of the lack of safety or outcome data in first trimester, and because the majority of skeletal growth and development is thought to occur in the 2nd or 3rd trimester. Dose for rapid correction: There is no consensus on what constitutes a very low vitamin D level, but a level of less than 15nmol/L, for example, would be considered as being very low by most clinicians. If the baseline vitamin D level is very low and the woman is in the 2nd or 3rd trimester of her pregnancy, then rapid correction may be required particularly if there are unmodifiable risk factors. In these cases it would be rational to use doses higher than 4000units/day (but not more than 10,000units/day) in the second or third trimesters (e.g. 7,000units/day for 6-7 weeks or 10,000units/day for 4-5 weeks to provide a cumulative dose of around 300,000 units). However, the higher doses should only be used with the input of an obstetrician and with monitoring of calcium levels. Large single doses of up to 120,000 units have been used from the 5th month of pregnancy onwards; but these large doses will only increase vitamin D levels for around 3 months and may need to be repeated. Other factors: When choosing a regimen, prescribers should also take into account: the severity of deficiency at baseline; whether unmodifiable risk factors (such as covering of the skin for religious/cultural reasons) remain an issue; the likelihood of compliance; the time of year; planned holidays in the sun; and product availability. Products: Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy should be managed with colecalciferol or ergocalciferol. There are licensed products that enable a dosing regimen of 4000units/day to be used and do not contraindicate use in pregnancy (e.g. five x 800units capsules of Fultium D3® or tablets of Desunin®). Products containing vitamin A (such as Cod Liver Oil) should be avoided because this is a known teratogen. Monitoring: To avoid maternal (and possibly foetal or neonatal) hypercalcaemia, we suggest that pregnant women being treated for vitamin D deficiency should have their serum calcium levels checked a month after starting treatment and then three months later, when steady state vitamin D levels have been achieved. Subsequent monitoring of calcium levels depends on duration of treatment and concerns about toxicity. If calcium levels are raised, then the prescriber should review the prescription for vitamin D or reduce the dose. Routine monitoring of vitamin D levels is not necessary but if they are re-checked, this should be 3 months after starting therapy, when steady-state has been reached. Calcium intake: Pregnant women should try to maintain an adequate calcium intake (700mg/day) through their diet. Background Pregnant women are at particular risk of vitamin D deficiency, with recent advice defining deficiency as being represented by a serum 25OHD level of <30nmol/L. (1) What constitutes an adequate level in pregnancy is still controversial and many suggest >50nmol/L to be adequate whilst some suggest >75nmol/L. (2-5) The consequences of vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy and breast-feeding are potentially quite stark. The developing infant is dependent on its mother for vitamin D, and since maternal vitamin D status determines the vitamin D status of the newborn, the development of rickets and other skeletal abnormalities is possible. (2;3;6-14) Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 1 Medicines Q&As Human breast milk contains low levels of vitamin D even when mothers are replete – therefore a fully breast-fed infant born to a mother who is deficient of vitamin D is likely to remain deficient and at risk of skeletal abnormalities unless an intervention is made. (6;10;12;14;15) There is therefore a good argument and support for correction of maternal vitamin D levels prior to and after delivery and whilst breast-feeding. (6;8;9;12) Indeed, in recent years a reemergence of rickets has been seen in the UK, with cases mainly affecting children from ethnic minorities. This reemergence is probably related to both maternal and infantile diet and lifestyle in particular groups (for example, in women who cover their skin). (6;11;14). In addition to the reasonably well described risks associated with vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy, observational research also suggests links between poor vitamin D status in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia, obstetric complications, gestational diabetes and bacterial vaginosis in the mother (16-18); transient hypocalcaemia and tetany in the new-born (19;20); and various diseases of childhood. (9) Conversely, a number of studies have reported that infants whose mothers had adequate vitamin D levels were larger at birth and had smaller fontanelles.(8;10;12;15) It is then widely accepted that for a variety of health reasons outlined above, pregnant women should have adequate vitamin D stores for their own requirements, for their developing foetus, and to build stores for early infancy particularly where they plan to breast-feed. Current DoH guidance makes recommendations in relation to routine supplementation in pregnancy and breast-feeding but does not address the issue of correction of vitamin D deficiency (i.e. 25OHD < 30nmol/L) in these situations.(13) This Q&A addresses specifically the issues associated with vitamin D dosing in pregnancy. It does not address identification of deficiency, and hence does not include information on screening and testing that might be necessary to determine vitamin D status in pregnant women. There is no consensus on exactly which pregnant women to test for vitamin D deficiency. However, if a pregnant woman is tested and found to be vitamin D deficient, then consideration should be given to correcting this deficiency. The Q&A answers the following questions using the best evidence we have been able to identify: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. What dose and treatment regimen could be used to correct vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy? When should vitamin D deficiency be corrected in pregnancy? Are high dose regimens (i.e. Up to 300,000 units cumulatively) safe for use in pregnancy? What available products are best to use to correct vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy? How often should a pregnant woman being treated for vitamin D deficiency be monitored? What is the role of calcium and vitamin D during pregnancy? 1. What dose and treatment regimens could be used to correct vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy? For routine supplementation, current DoH guidance recommends 10mcg (400 units) daily in all pregnant women (13); however, this will not correct deficiency in pregnancy where that has been identified. Consensus guidance on doses adequate to correct vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy does not exist and hence there is a need to interrogate the primary literature. We identified a number of studies investigating vitamin D dosing in pregnant women and these are summarised in the Appendix. (19;21-29) The majority of these studies were conducted in the second and third trimesters and as can be seen from the table they varied in design; duration; doses and products of vitamin D used; latitude, ethnicity, and sun exposure habits of participants; baseline maternal vitamin D levels and assay methods used to determine 25OHD. Differences in reported increases between one study (19) and the others with respect to rises in vitamin D levels may be explained by variations in the studies. As well as the range of outcomes reported varying between the studies, the range of doses investigated also varied significantly. The highest daily dose studied in pregnancy was 4000units/daily starting from weeks 12 – 16 and continuing to term (23) and the highest weekly dose was 35,000units/week, which was given between gestational weeks 26-29.(27) Single bolus doses used in later pregnancy ranged from 60,000units to 600,000units. (2426;28;29) The cumulative doses to which patients were exposed also varied between a range of 60,000 – 1,200,000 units, given as 600,000 unit doses at the 7th and 8th months in one study (26), and with no adverse pregnancy outcomes reported for this range.(19;21-29) Using the evidence base to determine recommendations for dosing is not easy given the variability outlined above and in the Appendix. The use of 1000units/day is too low a dose for correction of deficiency in pregnancy, particularly given that 10-15 minutes of direct exposure to sunlight can release up to 20,000 units of vitamin D into the circulation in Caucasians (though this time would be longer in people with pigmented skin). (6;15) Hence, many researchers Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 2 Medicines Q&As have logically inferred that doses similar to those used in the general (vitamin D deficient) population (i.e. around 300,000 units cumulatively)(1) are more likely to correct deficiency in pregnant women than the lower doses used for routine supplementation. The need for further research is widely acknowledged. (4;6;7;12;15;29). 2. When should vitamin D deficiency be corrected in pregnancy? Most of the studies cited involved women in the second or third trimesters of pregnancy; the majority of skeletal growth and development occurs during this period and hence treating particularly during this time is advisable. (8;14) In addition, since the first trimester is more likely to be associated with teratogenicity, treating during this time may be associated with greater theoretical risks. (30) A sensible overall dosing recommendation might, therefore, be a 300,000 unit cumulative dose given during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Whilst in the UK no specific guidance exists in relation to how best to achieve this cumulative dose in pregnant vitamin D deficient women, guidance does exist in other countries. (31-33) For example, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend a daily intake of 1000-2000 units with an upper limit of 4000 units/day; (32) the Italian Society for Osteoporosis recommends similar dosing and avoidance of single bolus doses >25,000 units;(31) and the French Society of Paediatrics recommends large single doses up to 80,000– 100,000 units, but only from the 7th month of pregnancy. (33) In our view, from the evidence base we have been able to identify, reasonable recommendations in relation to dosing for vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy might include: Using a low dose of vitamin D (e.g. 400 units (10mcg) as suggested by the DoH for routine supplementation) during the first trimester. (13) Consideration should be given to using corrective doses in the second and third trimesters, when skeletal growth and development occurs (8), if these are deemed necessary. Use of an oral corrective dose of 4000 units per day for up to 11 weeks to provide a cumulative dose of around 300,000units in the second or third trimester. There is no consensus on what constitutes a very low vitamin D level, but a level of less than 15nmol/L, for example, would be considered as being very low by many clinicians. If the baseline vitamin D level is very low and the woman is in the second or third trimester of her pregnancy then slightly faster or even rapid correction may be required particularly if there are unmodifiable risk factors. In these cases it would be rational to use doses higher than 4000units/day, but not more than 10,000units/day (1;34) in the second or third trimesters. E.g. a daily dose of 5000 units for 8–9 weeks or 7000 units for 6-7 weeks or 10,000 units for 4-5 weeks would provide a similar cumulative dose of around 300,000 units. The rationale for using no more than 10,000 units/day is due to the theoretical possibility of toxicity (1) and malformations (34) in humans if very high doses (i.e. >10,000 units/day) are used. However, it should be noted that this higher dose recommendation is not supported by any studies, but rather is an upper physiological limit for which limited safety data in pregnancy do not indicate a high possibility of harm. (34-37) Therefore we suggest that these higher doses should only be used with the input of an obstetrician and with monitoring of calcium levels. There is limited evidence to support the use of large single doses of vitamin D, such as 60,000 unit single doses used in the second trimester by two groups of researchers. (24;28) Though vitamin D levels were elevated for a time after dosing, they were not sustained throughout pregnancy and declined after 2-3 months. This means that there would be a need to repeat these large single doses. This, in addition to theoretical safety concerns about the use of large single doses of vitamin D mean that the daily dose regimens described above may offer a more reliable and theoretically, safer option. Once deficiency has been addressed and treatment moves on to maintenance, a dose consistent with that used in the general population is appropriate (i.e. 800units to 2000units/daily). (1) In determining the regimen to use the following are useful factors to consider: The severity of vitamin D deficiency (i.e. baseline vitamin D value) and the need for rapid correction. Whether there are un-modifiable risk factors (such as vegetarian diet or covering of the skin for cultural reasons) that may affect the ability to maintain vitamin D levels once deficiency is corrected. The trimester of pregnancy. Treatment should ideally begin after the first trimester because of the lack of data on its use in first trimester and also because the majority of skeletal growth and development is thought to occur after the first trimester. In addition, if a woman is already in her third trimester when vitamin D deficiency is identified, a higher dosing regimen over a shorter time period may be considered (e.g. up to 10,000units/day for 4-5 weeks to provide a cumulative dose of 300,000units). Whether tolerability and compliance issues are likely. For example, a high dose vitamin D regimen may involve taking a number of tablets to achieve the high dose and this could be problematic for some women. Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 3 Medicines Q&As Whether it is approaching summer or winter in the UK and/or whether any holidays in the sun are planned. In such cases it would be prudent to avoid using high doses used for rapid correction (i.e. 10,000units/day). Local availability of vitamin D products 3. Are there data to support the use of high dose regimens (i.e. up to 300 000 units cumulatively) during pregnancy? Safety data for high dose vitamin D regimens used during human pregnancy are limited. Of the studies in Appendix 1 that reported neonatal outcomes, none reported any adverse pregnancy outcomes. (19;23-27;29) The cumulative doses of vitamin D used by these studies were between 60,000 to 1,200,000 units given either as daily doses of up to 4000 units, weekly doses of up to 35,000 units or single bolus doses of up to 600,000 units). (19;23-27;29) Other human safety data that report neonatal outcomes are limited to case reports, usually relating to patients with concomitant conditions such as thyroid disease or patients who had taken a particularly high dose inadvertently. (34-37) These data suggest that vitamin D, used at high doses (up to 250,000 units/day) was not associated with an increased risk of congenital malformation, although obviously, the data are insufficient to confirm that there is unequivocally no risk. (34-37) The limited safety data that report neonatal outcomes in human pregnancy, relate to use in the second or third trimesters. (19;23-27;29;34-37) Use of high dose vitamin D in the first trimester should therefore be avoided as far as possible, due to the lack of safety data. In theory, high doses of vitamin D could cause maternal hypervitaminosis D and subsequently maternal, foetal and/or newborn hypercalcaemia. (34) Although it may also be true that the foetus is relatively well protected from excessive maternal levels by homeostatic mechanisms, the theoretical risk of maternal and foetal hypervitaminosis D or hypercalcaemia is a concern as it could lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes. In animal studies where extremely high relative doses were given to pregnant mice, rats, pigs or rabbits, facial and skeletal malformations, degradation of coronary smooth muscle, decreased rate of ossification of the proximal phalanges and supravalvular aortic stenosis were reported. Although there was no statistical analysis of the findings, a theoretical possibility of malformations in humans was raised if very high doses are used. (34) Therefore, it is suggested that single high doses of vitamin D are avoided (i.e. >10,000 units/day). (1;15) 4. What available products would be best to use to correct vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy? Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy should be managed with colecalciferol or ergocalciferol; however, no licensed high dose oral vitamin D products were available on the UK market at the time of writing (i.e. products giving >800units per unit dose). There are licensed products that enable a dosing regimen of 4000units/day to be used and do not contraindicate use in pregnancy (e.g. five x 800units capsules of Fultium D3® or tablets of Desunin®).(38;39) Products containing vitamin A (such as Cod Liver Oil) should be avoided because this is a known teratogen. More information on product selection is available from http://www.medicinesresources.nhs.uk/en/Communities/NHS/SPSE-and-SE-England/Medicines-Information/Discontinuation-Supply-Shortage-Memos/Vitamin-D-deficiency-andinsufficiency-available-products/ 5. How often should a pregnant women being treated for vitamin D deficiency be monitored? For non pregnant patients, the National Osteoporosis Society suggests that serum calcium should be checked a month after completing the loading regimen in case subclinical primary hyperparathyroidism has been unmasked. They state that routine monitoring of serum vitamin D levels is unnecessary (unless there are concerns about compliance or malabsorption) and that steady-state levels for vitamin D are reached three months after treatment begins.(1) In pregnancy, maternal, foetal or neonatal hypercalcaemia is of particular concern as it is hypothesised to result in an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. (34) Regular monitoring of serum calcium levels, as well as an awareness of the signs and symptoms of hypercalcaemia will help to prevent toxicity and allow timely intervention to be made if needed. (34) However, there is no consensus or guidance on exactly how often a pregnant woman being treated for vitamin D deficiency, or her neonate, should be monitored. Therefore we suggest that, for pregnant women being treated for vitamin D deficiency, it may be prudent to check maternal calcium levels a month after starting the regimen and then three months after starting the treatment (when steady state levels for vitamin D are likely to have been attained) as is suggested for the general population. (1) If the pregnant woman is still taking the treatment dose of vitamin D thereafter, calcium levels could be checked again three months later or sooner if there are concerns about toxicity. If calcium levels are raised, then the prescriber should review the prescription for vitamin D or reduce the dose. In the general population, re-checking of vitamin D levels is only suggested if there are concerns about malabsorption or compliance. (1) However, if there is a need to check serum vitamin D levels in pregnant or non pregnant individuals, it stands to reason that this should be done 3 Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 4 Medicines Q&As months after the last dose when steady state levels have been achieved. It might also be sensible to check neonatal calcium and vitamin D levels at delivery. 6. What is the role of calcium and vitamin D during pregnancy? Combined calcium and vitamin D products should not routinely be used to correct deficiency due to the risk of hypercalcaemia; instead pregnant women should try to have an adequate calcium intake (700mg) through their diet.(1;40) Calcium calculators (e.g. http://www.rheum.med.ed.ac.uk/calcium-calculator.php) are available to help patients and clinicians determine whether dietary modification and/or supplementation should be used. Limitations It is important to provide pregnant women and new mothers with advice on modifying their lifestyle to improve their vitamin D status. This document has not focussed on this aspect. The potential differences in efficacy between vitamin D2 and D3 are not addressed in this document Information on the management of vitamin D deficiency in the general population as well as a discussion about risk factors and target levels is available from National Osteoporosis Society Guidance This Q&A does not make recommendations on specific vitamin D products for a number of reasons. However, the reader is directed to NHS Evidence so that they can make a judgement on this. There are no current UK guidelines on treating vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy. This document does not provide information or guidance about the management of vitamin D deficiency in women who are breast-feeding or for their breast-fed infants. References (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) Vitamin D and Bone Health: A practical clinical guideline for patient management. Version 1.1. Accessed via www.nos.org.uk on 21/01/2014. National Osteoporosis Society Dror DK, Allen LH. Vitamin D inadequacy in pregnancy: biology, outcomes, and interventions. Nutr Rev 2010; 68(8):465477. Committee on Obstetric Practice. Vitamin D: Screening and supplementation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 118(1):197-198. Finer S, Khan SK, Hitman GA et al. Inadequate vitamin D status in pregnancy: evidence for supplementation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011; 91:159-163. Nassar N, Halligan GH, Roberts CL et al. Systematic review of first trimester vitamin D normative levels and outcomes of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205:208.e1-7. Dawodu A, Wagner CL. Mother-child vitamin D deficiency: an international perspective. Arch Dis Child 2007; 92:737740. Hyppönen E, Boucher BJ. Avoidance of vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy in the United Kingdom: the case for a unified approach in National policy. Br J Nutr 2010; 104:309-314. Leffelaar ER, Vrijkotte TGM, van Eijsden M. Maternal early pregnancy vitamin D status in relation to fetal and neonatal growth: results of the multi-ethnic Amsterdam Born Children and their Development cohort. Br J Nutr 2010; 104:108-117. Lucas RM, Ponsonby A-L, Pasco JA et al. Future health implications of prenatal and early-life vitamin D status. Nutr Rev 2008; 66(12):710-720. Pettifor JM, Prentice A. The role of vitamin D in paediatric bone health. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2011; 25:573-584. Shenoy SD, Swift P, Cody D. Maternal vitamin D deficiency, refractory neonatal hypocalcaemia, and nutritional rickets. Arch Dis Child 2004; doi: 10,1136/adc.2004.065268. Wagner CL, Greer FR, Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 2008; 122:1142-1152. Vitamin D - advice on supplements for at risk groups. Ref: CEM/CMO/2012/04. Gateway ref: 17193. Welsh Government., Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety., The Scottish Government., and Department of Health. Wharton B, Bishop N. Rickets. Lancet 2003; 362(9393):1389-1400. Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Assessment of dietary vitamin D requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79:717-726. Christesen HT, Falkenberg T, Lamont RF et al. The impact of vitamin D on pregnancy: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012; 91:1357-1367. Grundmann M, von Versen-Höynck F. Vitamin D - roles in women's reproductive health. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2011; 9:146-157. Poel YHM, Hummel P, Lips P et al. Vitamin D and gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2012; 23:465-469. Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 5 Medicines Q&As (19) (20) (21) (22) (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28) (29) (30) (31) (32) (33) (34) (35) (36) (37) (38) (39) (40) Brooke OG, Brown IRF, Bone CDM et al. Vitamin D supplements in pregnant Asian women: effects on calcium status and fetal growth. Br Med J 1980; 280:751-754, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.280.6216.751. Camadoo L, Tibbott R, Isaza F. Maternal vitamin D deficiency associated with neonatal hypocalcaemic convulsions. Nutrition Journal 2007; 6:23. Datta S, Alfaham M, Davies DP et al. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant women from a non-European ethnic minority population - an interventional study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; 109:905-908. Delvin EE, Salle BL, Glorieux FH et al. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: Effect on neonatal calcium homeostasis. The Journal of Pediatrics 1986; 109(2):328-334. Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC et al. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double-blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26(10):2341-2357. Kalra P, Das V, Agarwal A et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on neonatal mineral homeostasis and anthropometry of the newborn and infant. Br J Nutr 2011; 108:1052-1058. Mallet E, Gügi B, Brunelle A et al. Vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy: a controlled trial of two methods. Obstet Gynecol 1986; 68:300-304. Marya RK, Rathee S, Lata V et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1981; 12:155-161. Roth DE, Al Mahmud A, Raqib R et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of high-dose prenatal third-trimester vitamin D3 supplementation in Bangladesh: the AViDD trial. Nutrition Journal 2013; 12:47-doi:10.1186/1475-2891-12-47. Sahu M, Das V, Aggarwal A et al. Vitamin D replacement in pregnant women in rural north India: pilot study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009; 63:1157-1159. Yu CKH, Sykes L, Sethi M et al. Vitamin D deficiency and supplementation during pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009; 70:685-690. Introduction. In: Schaefer C, Peters P, Miller RK, editors. Drugs during pregnancy and lactation. Second Edition. London, UK: Academic Press, Elsevier, 2007: 2. Adami S, Romagnoli E, Carnevale V et al. Linee guida su prevenzione e trattamento dell' ipovitaminosi D con colecalciferolo. Guidelines on prevention and treatment of vitamin D deficiency. Reumatismo 2011; 63(3):129-147. Vitamin D deficiency: Evidence, safety and recommendations for the Swiss population. March 2012. Federal Department of Home Affairs FDHA., Federal Office of Public Health FOPH, and Consumer Protection Directorate Vidailhet M, Mallet E, Bocquet A et al. Vitamin D: Still a topical matter in children and adolescents. A position paper by the Committee on Nutrition of the French Society of Paediatrics. Arch Pediatr 2012; 19:316-328. Use of vitamin D in pregnancy. May 2013. Version 1.1. Accessed via www.toxbase.org on 21/01/2014. UK Teratology Informaton Service (uktis). Vitamin D. REPROTEXT® Database (electronic version). Truven Health Analytics, Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (cited: December 2012). Vitamin D. In: Briggs GG, Freeman RF, Yaffe SJ, editors. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation. Ninth edition. Philadelphia, USA.: Wolters Kluwer Health; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins., 2011: 1577-1579. Vitamin D group. In: Schaefer C, Peters P, Miller RK, editors. Drugs during pregnancy and lactation. Second edition. London,UK.: Academic Press, Elsevier., 2007: 475-476. Summary of Product Characteristics. Desunin 800 IU tablets. Date of revision of the text: 13/06/2013. Accessed via www.emc.medicines.org.uk on 21/01/2014. Meda Pharmaceuticals. Summary of Product Characteristics. Fultium-D3 800IU capsules. Date of revision of the text: 29/06/2013. Accessed via www.emc.medicines.org.uk on 21/01/2014. Internis Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Patient Information Leaflet: Healthy Bones - facts about food. National Osteoporosis Society. June 2011. Accessed via from www.nos.org.uk, 31/10/2013. Bibliography National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2008). Antenatal Care CG6. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chappell LC. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 16. Vitamin supplementation in pregnancy 2009. Available via http://www.rcog.org.uk/ Quality Assurance Prepared by Sheena Vithlani, Principal Medicines Information Pharmacist, London Medicines Information Service, Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow. Date Prepared 30th January-July 2013 Contact: nwlh-tr.medinfo@nhs.net Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 6 Medicines Q&As Checked by Alexandra Denby, Regional MI Manager, London Medicines Information Service, Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow. Date of check January 2014 Search strategy Medline: 1950 to present: (exp COLECALCIFEROL/ or exp ERGOCALCIFEROLS/ or exp VITAMIN D/) and (PREGNANCY OUTCOME/ or PREGNANCY/ or PREGNANT WOMEN/ or exp PREGNANCY TRIMESTERS/). Limit to: Humans and Female and English Language. EMBASE 1980 to present; (PREGNANCY/ or REPRODUCTION/ or MOTHER FETUS RELATIONSHIP/ or PREGNANT WOMAN/ or FIRST TRIMESTER PREGNANCY/ or SECOND TRIMESTER PREGNANCY/ or THIRD TRIMESTER PREGNANCY/ or TERATOGENICITY/) and (*ERGOCALCIFEROL/ or *COLECALCIFEROL/ or *VITAMIN D/; or VITAMIN D DEFICIENCY/). Limit to: Human and English Language] Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 7 Medicines Q&As Appendix 1 Studies of vitamin D use during pregnancy There are limitations to these studies, such as small patient groups, none provide data for use in first trimester, not all provide anthropomorphic data for the newborns and exact treatment durations/cumulative doses Dose and regimen Average vitamin D levels Other endpoint(s)/outcomes/major Estimated during pregnancy limitations 25(OH)D (nmol/L) cumulative (week/month of (values reported as mean Values quoted as mean or median averages vitamin D gestation of dose) or median) Unless specified, values are quoted for Study details dose in Oral dosing unless intervention vs. placebo/control group at pregnancy specified baseline (before vitamin D) and at delivery. After (maximum Baseline *route unclear from (ns=not statistically significant vs. (change) iu vitamin D) literature placebo/control) The only significant difference was in fontanelle size, which was greater in the Vitamin D2 Brooke (1980) (19) control group (p<0.05). 1000units/day (from 28,000 to 168 20.2 Randomised, double Hypocalcaemia occurred in 5 infants in the week 28-32 to term). 56,000 to (+150) blind study. Women from control group and none in the treatment group N=59 Indian subcontinent living (p<0.01). in the UK (latitude 51.5o, Incidence of infants considered small for all seasons). Mean gestational age was 28.6% vs. 15.3% in Matched placebo. 16 vitamin D values stated control vs. treatment group (ns). 0 20.0 N=67 (-4) Cord blood vitamin D: 10.2nmol/l vs. 137.9nmol/l Only 58 women (73%) had their levels rechecked at delivery. Vitamin D levels were Datta (2002) (21) Vitamin D considered ‘normal’ at delivery for 60% of Interventional programme 800unitswomen (35/58) using this regimen. for women from Asia, 1600units/day for 6 Middle/ Far East and Max Choice of dose depended on level at week 36. months of Africa living in Cardiff, UK possible 14 28 (+14) There are many limitations to this study, such pregnancy. (latitude 51.4o). Mean 288,000 as lack of detail regarding how many women Trimester at point of levels stated. Study were treated with each dose, when treatment initiation not period/season was started, and the loss of 27% to follow-up. documented. N=80 not documented. No neonatal outcome measures were presented. Delvin (1986) (22) Infant vitamin D and calcium levels (measured Vitamin D3 Randomised study in at 4 days) were significantly higher those born 1000units/day (from 56,000 65 French Caucasian to mothers who were treated with vitamin D week 27-term).N=20 women living in Lyon, Not noted (45 vs. 17.5nmol/L, p<0.0005). Rate of infant France (latitude 45.7o). weight gain was similar. Study period; December No neonatal outcome measures were Control. N=20 0 33 to June. Mean values presented. stated. Neonatal vitamin D levels were 45.5nmol/L, 57nmol/L and 66nmol/L respectively in the 67,000 to 400units/day N=166 79 (+17) 400units/day, 2000units/day and 78,400* 4000units/day groups respectively (p<0.0001). Sufficient vitamin D levels were seen in Hollis (2011) (23) 39.7%, 58.2% and 78.6% of the neonates Randomised, double2000units/day 336,000 to respectively (p<0.0001). 98 (+36) blind study in women of N=167 392,000* There were no differences between the groups Hispanic, African and 58-61 in terms of gestational age or birth weight, or Caucasian descent living level of care required for the newborn. in the USA (latitude 32o). 39.4 (Black) Baseline levels of vitamin D (approximately Study period covered all 59.3 60nmol/L) indicated that the women included 672,000 to seasons. Treatment was (Hispanic) could not be considered vitamin D deficient. 784,000* started from between 74.6 There was a high correlation between vitamin week 12-16 and (Caucasian) D levels one month prior to delivery and at continued through to 4000units/day 111 delivery, and these values were used for the *cumulative term. Mean values N=169 (+49) 92 women missing delivery values. Levels of dose stated. ≥ 80nmol/L were achieved by 52.3%, 79.5% dependant and 83.9% taking 400IU, 2000IU and 4000IU on delivery respectively (p<0.0001 for 2000IU and 4000IU date vs. 400 IU). Kalra (2011) (24) Prospective longitudinal cohort. Indian women living in North India (latitude 26.8o). All were treated with 1g elemental calcium. Median values stated. Study period (season) not documented Vitamin D3 60,000units as a stat dose in the second trimester N=48 Vitamin D3 120,000units as a stat dose in the second and third (28 weeks) trimesters N=49 60,000 32 26 (-6) 120,000 32 59 (+27) Statistically significant differences in birth weight (~0.3kg), birth length (0.85cm), head circumference (0.85cm, all greater in the treatment groups) and diameter of anterior fontanelle (0.75cm smaller in the treatment group) were seen between the treatment and control groups at birth and persisted until 9 months of age. Single large doses increase vitamin D levels Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 8 Medicines Q&As Marya (1981) (27) Interventional study in Indian women living in North India (latitude 28.8o). Season not documented. Mallet (1986) (25) Randomised study in French Caucasian women living in the North of France (latitude 49.4o). Study period: winter. Sahu (2009) (28) Randomised study in Indian women living in North India (latitude 26.8o). Pooled results for summer and winter All women were given 1g elemental calcium/day and advised to get at least 60mins sunexposure/day on face, forearms and hands. Median values stated. Roth (27) Randomised study in women living in Bangladesh (latitude 23o). Mean values stated.Study period; autumn. . Yu (2009) (29) Randomised, controlled study in the UK (latitude 51.5o) with women from mixed ethnicity (Indian Asian, Middle Eastern, Black, and Caucasian). Women randomised within each ethnic group. Vitamin D deficiency was seen in 47%, 64%, 58% and 13% respectively. Median vitamin D values stated. Study period over several seasons. Not reported Control N=43 0 Vitamin D3 1200units/day (from week 28-term).N=25 75,000 Vitamin D2 600,000 units as a stat dose in months 7 and then 8. N=20 1,200,000 Control. N=75 0 Vitamin D3 1000units/day (from week 28-term).N=21 90,000 Vitamin D2 200,000units as a stat dose *(7th month). N=27 200,000 26 (+16 vs. control) Control. N=29 0 9 Vitamin D3 120,000units as a stat dose at 5th and then the 7th month. N=37 (group C) Vitamin D3 60,000units as a stat dose at 5th month. N=35 (group B) 39 Maternal and cord blood calcium levels higher in treatment groups compared to control. Statistically significant only for stat dose group (primary outcome). Cord blood vitamin D levels not tested. Increased neonatal birth weight in both treatment groups (2.89kg in daily dose group and 3.14kg in stat dose group) compared to control group (2.73kg) (p≤0.05). Not tested 25 (+15 vs. control) Not noted 240,000 40 53 (+13) 60,000 33 31 (-2) Control N=14 (group A) 0 26 24 (-2) 35,000units/week (26-29 weeks to term). N=80 378,760 (range 35,000560,000) 134 (+90) 44 Placebo. N=80 0 Vitamin D2 800units/day (from week 27-term). N=60 72,000 26 Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 45% 42 (+16) Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 13% Vitamin D3 200,000units as a stat dose at week 27. N=60 200,000 26 Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 42% 34 (+9) Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 7% 25 27 (+2)Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 40% Control. N=59 0 39 (-5) Vitamin D <25nmol.L: 50% for around 2.5-3 months, hence the apparent lack of effect in the 60,000unit group. However, both doses appeared to have positive effects on neonatal outcomes. Cord blood vitamin D levels similar across active treatment groups. Cord blood levels of vitamin D at delivery were greater in mothers who had been treated; 1518nmol/L vs. 5nmol/L. Infant birth weights were not significantly different between groups. Treatment regimens were equally effective. One case of delayed neonatal hypocalcaemia was observed in the control group (on day 6). Mean daily sun exposure was 2.5 hours in the summer and 4 hours in the winter. Target level of 80nmol/L achieved by 34% of women in group C, 5.7% in group B and 7% in group A. A single dose of 60,000 in the second trimester was not able to significantly increase the maternal vitamin D concentration at delivery. Neither dose induced hypercalcaemia. No neonatal outcome measures were presented. Cord blood levels of vitamin D at delivery were greater when mothers who had been treated; 103nmol/L vs. 39nmol/L. Vitamin D levels >50nmol/L were attained by100% of mothers (97% of mothers had levels ≥80nmol/L) and 95% of neonates in the treatment group compared with 21% (6.3%) and 19% respectively in the placebo group. There were no significant between-group differences in birth weight, birth length or head circumference. 35,000 units/week did not induce hypercalcaemia. Cord blood levels of vitamin D at delivery were greater in the treatment groups mothers; 26-27nmol/L vs. 17nmol/L. No differences in infant birth weights between groups. Target level of 50nmol/L achieved by 30% of women in the treatment groups at term and only 8% of babies at birth. This suggests that 800 units/day may be inadequate to raise the levels sufficiently Available through NICE Evidence Search at www.evidence.nhs.uk 9