Write a brief summary of chapters 1 to 3 of the Bhagavad Gita. Try to

advertisement

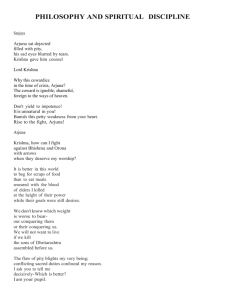

Write a brief summary of chapters 1 to 3 of the Bhagavad Gita. Try to put it into your own words. Before writing this essay, I did not read a great deal about the Gita. To expand my understanding a little, I have read the notes in the teacher training manual and the introduction to the GIta by Kknath Easwaran in the Nilgiri Press version. I also listened to a Radio Four programme with Melvyn Bragg about the Gita and its timeless message. The Bhagavad Gita – The Song of the Lord To write a brief summary of any part of the Gita seems to me, to be a near impossible task. Having read chapters one to three several times and considered them in the light of the rest of the Gita, I recognise that most paragraphs are filled with metaphors, imagery, analogies and invite deep and detailed philosophical discussion. Take, for example these lines from Chapter One; “Then Sri Krishna and Arjuna, who were standing in a mighty chariot yoked with white horses, blew their divine conchs. Sri Krishna blew the conch named panchjanya and Arjuna blew that called Devadatta.” For me this invites detailed literary discussion about the image of the white horses, perhaps representing purity or innocence; cleanliness before any blood has been shed? Or are the horses white because Krishna is there? The enlightened one, placed to ensure that Arjuna acts with integrity, in a righteous way and with spiritual awareness. I then question the symbolism of the conchs, why are they ‘divine’ and what meaning is there in the names they have been given? These few lines can be dissected and analysed in great detail and yet, as the text progresses, it becomes even more complex in the sense that the imagery and symbolism continues to appear in abundance but we are also invited to enter into a deep and philosophical musings. Concepts and notions are introduced which lead us to consider universal questions about life that, for thousands of years have been, and still are, at the heart of most religions and spiritual endeavours. Each concept invites further questioning and the discussion that sprouts from a short paragraph branches out in many directions, growing like a tree, blossoming at times and wilting at others depending often on the individual viewpoint and experience of the reader. To complicate things further, the reader needs to understand dharma and karma, the two concepts which are the essence of Hinduism. “The Gita, like other Hindu scriptures, takes them for granted, not as theoretical premises but as facts of life that can be verified in personal experience.” (Eknath Easwaran) So, before I try to summarise chapters one to three as briefly as possible, I first find it necessary to say that in doing this I feel that I am doing the text an injustice. I will leave much unsaid and unexamined but in my own time will return to the text and examine it more substantially and at greater length. Background The Bhagavad Gita is part of a text called The Mahabarata“. Many Historians surmise that the Mahabarata might well be based on actual events, culminating in a war that took place somewhere around 1000 B.C. The Gita is believed to be written sometime about the time of the start of the Common Era. It is often argued that The GIta was written in isolation from The Mahabarata, as an Upanishad and inserted into the epic at the appropriate place. It was adopted as a Hindu scripture and, like many of the Hindu texts is believed to be a record of a direct encounter with the divine. “Tradition calls these stories shruti: literally “heard”, as opposed to learned; they are their own authority. There is further debate amongst historians, philosophers and theologists as to whether or not the GIta set out to synthesise various beliefs and philosophies that were occurring at that time. Society was becoming increasingly pluralistic and there would have been major tensions amongst communities and within families. Many young people were leaving their homes, disappearing into forests, practising yoga and were focussed on trying to achieve moksha, (liberation, salvation, illumination). They would have been challenged by more traditional people concerned with society, duty and dharma. The Gita appears to embrace this diversity in the sense that Arjuna is in turmoil, not knowing the right way to act at this point in his life. Torn between his duty as a warrior, his duty as a family member and his instinct to live righteously, with integrity and compassion. Chapter One – The War Within Chapter One essentially sets the scene for The Gita. We are on a battlefield waiting for a war to begin which is a result of a struggle for power between two sets of brothers, the Pandavas and the Kauravas. There are good reasons why both sets of brothers can claim the throne. These are detailed in earlier sections of The Mahabharata. The scene is set through a description given to Dhritarashtra by Sanjaya. Dhritarashtra is the old, blind king who currently rules the kingdom of Hastinapura and who wants his son, Duryodhana, to succeed him on the throne. Sanjaya is not actually on the battlefield but has been given the gift of divine sight by Vyasa, the composer of The Gita to report all that is happening to the king. Duryodhana is on the battlefield ready to fight for the Kauravas. As is his cousin, Arjuna, who is fighting on the side of the Pandavas to defend his older brother’s claim to the throne. Alongside Arjuna is Krishna. Krishna is cousin to both sets of brothers and known as a great warrior, but in the latter parts of the Gita, he is gradually revealed to be God. In order to be neutral, he offered his army to one group of brothers and himself in a noncombative role to the others. The Kauravas took his army and the Pandavas accepted him. He is positioned as Prince Arjuna’s charioteer. In this role he can advise and encourage Arjuna without fighting himself. So, Sanjaya describes the scene on the battlefield to Dhritarashtra and explains that Duryodhana is poised and celebrating his army but also recognises the strength of the opposition. He describes the noise made by the opposition, Arjuna’s army, as they blow their conchs; “the noise tore through the heart of Duryodhana’s army. Indeed, the sound was tumultuous, echoing throughout heaven and earth.” By referring to ‘heaven and earth’, is Sanjaya alluding to the fact that the Gita is concerned with something far bigger than what is momentarily occurring on this battlefield, something more universal, eternal and spiritual? Infact, as Eknath Easwaran highlights in his notes in the Nilgiri Press version of the Gita, this is a concept that is hinted at in the Gita’s opening passage; “at Kurukshetra on the field of dharma”. The suggestion here being that the battle takes place “not only at Kurukshetra but also on the elusive “field of dharma”, the spiritual realm where all moral struggles are waged.” I will return to the concept of dharma and discuss it in greater detail shortly. Sanjaya goes on to explain that having blown his conch and seemingly psyched himself up to fight, Arjuna has serious misgivings. He asks Krishna to drive his chariot between the two armies so he can see those “assembled to fight”. Arjuna sees amongst the enemy “fathers and grandfathers, teachers, uncles and brothers, sons and grandsons, in-laws and friends,” and no longer feels he can fight. He has respect for these people. Amongst them are his relatives and old teachers. Many he does not know personally but he still values their place in society and sees their parallels in his own life. He has no desire to fight, “no desire for victory”. There is nothing that could make him want to kill these people and become a sinner. No matter what wrong they have done, many are still family and Arjuna believes that by killing members of his own family, “the family will decline, ancient traditions will be destroyed and the family will lose its sense of unity”. It is the duty of family members to be loyal to their family. Once again, the Gita is asking us to consider the concept of ‘dharma’. As touched upon in my introduction, dharma is a concept which lies at the heart of Hinduism. It is a difficult concept to translate concisely. In Sanskrit, dharma literally means ‘to support, to bear up’, but it has a much broader definition than this. “Dharma is divinely given; it is the force that holds things together in a unity, the centre that must hold if all is to go well. Dharma means the essential order of things, an integrity and harmony in the universe and the affairs of life that cannot be disturbed without courting chaos. Thus it means rightness, justice, goodness, purpose rather than chance.” (Eknath Easwaran) Your dharma is your duty, your duty in a descriptive sense, i.e. what you are, what you are like and, in a prescriptive sense, i.e. what you should be doing. In a descriptive sense, Arjuna is a warrior but he struggles with what this prescribes him to do. His duty as a warrior opposes his duty as a son, a brother, a husband, a cousin. Although, Arjuna is aware that it is his duty as a warrior to fight and that he has a duty to serve his brother (and honour his wife who has been wronged by the Kauravas), but he also knows he has a duty to his extended family to maintain equilibrium in the ‘process of spiritual evolution’ begun by his ancestors. This conflict is exacerbated no doubt by his certain ‘belief’ in the law of karma. “The law of karma states unequivocally that though we cannot see the connections, we can be sure that everything that happens to us, good or bad, originated once in something we did or thought. Karma is an educative force whose purpose is to teach the individual to act in harmony with dharma – not to pursue selfish interests at the expense of others, but to contribute to life and consider the welfare of the whole.” (Eknath Easwaran) Arjuna says, “These signs bode evil for us. I do not see that any good can come from killing our relations in battle.” He cannot fight, he believes he will be punished, he knows that killing his relations will bring him no personal happiness. He would rather die himself and so at the end of chapter one he throws down his bow and arrows in the middle of the battlefield and turns to Krishna with this enormous personal and social problem and looks to him for a solution. Therefore, the action of the Gita is actually a discussion; Krishna’s answer, a deeply philosophical discussion which is still resonant today, 2000 years after it was written. Chapter Two – Self Realisation “Arise with a brave heart and destroy the enemy.” Says Krishna. On one level, Krishna is saying, come on, get up, what’s your problem? Do not be weak, you are a warrior, get up and fight, but on a deeper level, he is challenging Arjuna to question this battle and his role in it. “As they stood between the two armies, Sri Krishna smiled and replied to Arjuna, who had sunk into despair.” For me, this line is particularly poignant as Krishna smiles. Perhaps because I know he will later be revealed as God, I read more into this, but even without this knowledge, one might question, what is there to smile about? To me, this smile gives him an air of serenity, an otherworldliness. The aura of one who is enlightened and can detach himself from the circumstances in a real sense, and view the situation from a more cosmic point of view. Infact, this is precisely what Krishna tells Arjuna to do. “Seek refuge in the attitude of detachment and you will amass the wealth of spiritual awareness.” Krishna basically tells Arjuna that he has nothing to worry about. He explains that beneath what Arjuna regards as himself is a metaphysical self called the Atman. This is eternal and the same in one and all. He insists that what Arjuna is concerning himself with (essentially, a physical body and the other physical bodies on the battlefield, embedded in social relationships with one another), is all superficial. Beneath this there is an unchanging reality. “The impermanent has no reality; reality lies in the eternal.” Krishna tells Arjuna that he should fight because the experiences of the battle will be only fleeting, they come and they will go. He is really telling Arjuna that whatever happens on the battlefield, whatever he and others experience, will not actually change or affect them; will not even hurt them, “The self cannot be pierced by weapons or burned by fire.” By some, the Atman may be interpreted to be like a soul or spirit. A life force that exists before birth and will continue to exist after death. However, I somehow imagine, that when people consider their spirit, especially in western society and religions, they give it some of their personality; it is still very much a part of them and who they are. There is a similar concept in Hindu philosophy, that is the ‘jiva’. This is a living soul within an individual but it is finite and will die with the physical body. In contrast, the self that Krishna refers to, the Atman or Purusha, is a bigger, more universal spirit which is the same in all and has been released from “the ego cage of “I”, “me” and “mine””. It is the innermost soul which “pervades the universe and is indestructible; no power can affect this unchanging, imperishable reality. The body is mortal, but that which dwells in the body is immortal and immeasurable.” Krishna even offers Arjuna reincarnation as consolation suggesting that if Arjuna really believes that “the self dies”, he still should not grieve as rebirth is inevitable. However, he does go on to explain that rebirth is in fact for the ignorant, those who have hearts are full of selfish desires and are motivated only by the fruits of their actions. I have often wondered how differently people would live their lives, particularly in the Western world, if they believed, beyond question, that rebirth was as certain as death. In many respects this could cheapen the value of life and so we may live more carelessly or less compassionately, but there is also the possibility that, with this belief, people would naturally be less attached to selfish desires, be more patient, no longer demanding instant gratification; freed from the need to fit so much into one life? Krishna’s message goes further than this though, he is not telling Arjuna to abandon selfish desires because he can pick them up again in another life, but is saying that by doing so he will discover “a place of deep joy and peace within himself – his true nature”. (Brian Cooper) He will then unify his consciousness, have peace of mind and pass from ‘death to immortality’. In this chapter, Krishna is encouraging Arjuna to practice Sankhya Yoga, the yoga of knowledge. He urges Arjuna to become ‘wise’ by withdrawing and controlling his senses. If he can achieve this he will no longer crave sense pleasures, will no longer lust after anything, desire possessions or results. Consequently, he will see more clearly, will not experience anger or frustration through disappointment or dissatisfaction and will be at peace, neither elated nor depressed but calm and balanced. Chapter Three – Selfless Service Arjuna is still perplexed. Whether or not Krishna has convinced him that he has an immortal soul, his concern is what he should do now and wonders if he should do anything at all. If he is to withdraw his senses and acquire spiritual wisdom perhaps he should only meditate and not act at all. However, Krishna has already told him that it is his duty as a warrior to fight so Arjuna knows that there is more to this argument and some dynamic action still has to be taken. What Krishna then explains is that of course, Arjuna must act. If only to survive, humans must act, but they should act selflessly. “Arjuna must work not for his own sake, but for the welfare of all. Krishna points out that this is a basic law underlying all creation. Each being must do his part in the grand scheme of things, and there is no way to avoid this obligation – except perhaps by complete enlightenment which loosens all the old bonds of karma.” (Diana Morrison) So here the Gita is concerned with the previously mentioned concepts of karma and dharma. Arjuna should act without attachment to the fruits of his actions. He must act as it is his duty and to not act will cause “cosmic chaos” and only have repercussions for him later. However, he must act without expectation; he should stay free “from the fever of the ego.” If he acts for himself and for personal gain, he will not act wisely, he will not make clear judgements and skilful decisions. However, if he devotes his actions to Krishna, to the devas, (the divine beings), he will act selflessly, sacrifice his actions and will then automatically be fulfilled, satisfied and nourished. The devas will meet his needs, everything will be just fine, everything will be as it is meant to be as he will be acting in accordance with the law of karma and within the boundaries of his own dharma. Krishna does touch upon his previous argument again. He reminds Arjuna that to act selflessly he must withdraw the senses, rise above the mind and the intellect and let his true self, the Atman, rule. If the Atman is a universal self, the same in one and all, being in touch with this, will mean that Krishna is in touch with the divine and will naturally act in the way that is right and true. Conclusions To conclude, I will try and put into words how I think one might interpret the Gita’s message for use as a guide in life today. This will also reflect how its message may influence me in my role as a teacher. Act in life because it is your duty and it is the right thing to do. Do not act because you alone have something to gain from your actions. Do not be selfish, be selfless. Focus on what you can do and should, not what you can’t and should not. “You have the right to action, but not to the fruits of action”. Be measured and considerate, act skilfully and not impulsively but listen to your instincts too. If you are calm and selfless, your instinct may be your true self talking? Take time to meditate. Rise above all that is unimportant; gossip, pettiness, scandal, negativity and ignorance. As a teacher or a parent, do what needs to be done for your students or children because it is what they need, not because it makes them an extension of yourself or a reflection of you. Meet their physical and emotional needs for their sake, to equip them with the necessary skills to carry them through life. Give them stability, security, love and peace of mind. Practice ahimsa, wish no harm. Be kind, be patient, dedicate your actions to others, to those you love and care for or those less fortunate. Be caring and conscientious but also do not be afraid to tell others to pull their weight. Everyone has a duty to do their bit. Work hard in your ‘job’ because you have chosen that as your role in life so it is now your duty. Fulfil your intentions but ensure these intentions are well thought out and set for the right reasons. Be an example to others. Of course we need money, shelter and clothes but do not be unnecessarily materialistic. Do not clutter your life and your mind with an excess of useless, confusing and impeding material. Accept that you may have or want ‘nice’ things in your life but question why you want them. Be clear about what really matters. When practising yoga, give all that you do 80 % of your effort, save something for your breath. Find a place to be soft, to relax and surrender. Practice without attachment to the final posture and apply this theory to everything you do in life. That is, you work hard, put the effort in, act with integrity and do the best you can, but also accept where you are and surrender when you need to. Know what the results of your actions will be but do not desire these results. Do not waste your time and energy on the unnecessary, work hard at what is necessary. Accept who you are, what you are and how others behave. Love and respect others in your life and do not act exclusively for personal gain. Enjoy the moment, take what you can from the moment that you are in, be satisfied with where you are and what you have.