Topic 5 notes

advertisement

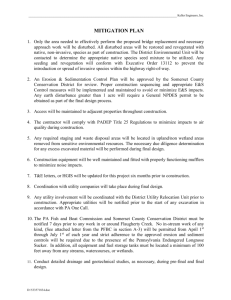

MSc Economic Evaluation in Health Care WELFARE ECONOMICS Topic 5. Resolving Pareto non-comparability: (i) The compensation principle (ii) Social Welfare Functions Pareto non-comparability The strength of the Pareto Principle lies in the fact that by making the weak assumption of ordinality, the desirability of certain social states can be determined. The weakness lies in the fact that the Pareto ranking of states is incomplete and that there exists Pareto noncomparability (remember that Pareto non-comparable states are ones in which some households are made better off but others are made worse off in moving from one state to another). This leads to two main deficiencies with the Pareto Principle: 1. The Pareto Principle is unable to rank every Pareto optimal allocation superior to a non-optimal allocation. 2. The Pareto Principle is unable to rank different Pareto optimal allocations relative to one another. (i) The compensation principle and the Pareto Principle An attempt to overcome the first deficiency and increase the power of the Pareto Principle is known as the compensation principle. Two different versions of the compensation principle have been proposed: 1. The compensation principle proposed by Kaldor says that state a is preferred to state b if, in state a, it is hypothetically possible to undertake a costless lump-sum redistribution and achieve an allocation that is superior to state b according to the Pareto Principle. In other words, if the gainers from the move to state a can hypothetically compensate the losers so that everyone is better off then state a is preferred to state b. 2. The compensation principle proposed by Hicks says that state a is preferred to state b if, in state b, it is not hypothetically possible to undertake a costless lump-sum redistribution and achieve an allocation that makes everyone as well off as in state a. In other words, if the losers from the proposed move cannot hypothetically bribe the gainers not to make the move then state a is preferred to state b. Two examples of the two compensation principles: 1. Gainers gain £2 million, losers lose £1 million 2. Gainers gain £1 million, losers lose £2 million 1 We will concentrate on the Kaldor compensation principle. The compensation principle will always rank a Pareto optimal allocation superior to a non-optimal allocation, thus negating the first deficiency of the Pareto Principle, outlined above. Problems with the compensation principle 1. The redistribution is hypothetical only (if it were a real distribution then the entire exercise would be a direct application of the Pareto Principle). 2. The hypothetical redistribution is assumed to be costless. 3. The Pareto Principle is still unable to rank different Pareto optimal allocations relative to one another (deficiency 2, outlined above). That is, there are still Pareto noncomparable states. 4. The compensation principle may lead to contradictions (as shown by the Scitovsky Paradox), where a move from state a to state b may satisfy the compensation principle, but so may a move from state b to state a. (ii) Social welfare orderings and social welfare functions The aim of welfare economics is to provide a framework that permits meaningful statements to be made about the desirability of certain social states (allocations of resources) to others. We would ideally like this social ordering to be: 1. complete, so that every social state can be compared to another; and 2. consistent, so that the ranking is reflexive and transitive. A complete and consistent ranking of social states is called a social welfare ordering (SWO). Just as with household preferences, if a continuity assumption is also made the SWO can be represented by a social welfare function (SWF) that assigns a number to each social state so that they might be ranked. We cannot achieve an SWO without someone making value judgements about the desirability of different social states (i.e. we have to come to some decision as to how household preferences are to be aggregated). Value judgements are statements of ethics that cannot be found to be true or false on the basis of factual evidence. The value judgements found in an SWO may be weak (i.e. broadly accepted) or strong (i.e. controversial). A weak value judgement that we have used up until now to rank social states is the Pareto Principle. However, as we have seen this does not provide a complete ranking of social states because some states are Pareto non-comparable. Therefore the Pareto Principle alone does not achieve the desirable properties of an SWO. 2 Another weak value judgement that is commonly made in welfare economics is individualism, which requires that the preferences of the individual households should matter when determining the SWO. Individualism imposes certain informational requirements on the choice of an SWO. These requirements concern each household’s preferences over social states (the measurability requirement), and how a given level of utility for any household compares with that of another household (the comparability requirement). The value judgements and informational requirements limit the set of SWO possibilities from which the decision-maker can choose. In summary, we are concerned with the ethical problem of resolving the conflict inherent in finding the normative solution to the distribution problem. Specifically, some households in the economy prefer state x to state y and others prefer to y to state x. Given that household preferences should be taken into account, how should the policy-maker aggregate such conflicting preferences into a single SWO? The framework A social state is identified by an allocation of N goods to the H households in the society. That is, an allocation x is an N*H vector where x ih is the amount of good i consumed by household h. The objective is to derive an SWO of social states from the households’ orderings of social states. The means of aggregating the household orderings into the SWO is called the social choice rule (SCR). The most general form of the SWF is called the Bergsonian SWF (sometimes called the Bergson-Samuelson SWF). This is simply a function f(Uh) of the utility levels of all households such that a higher value of the function is preferred to a lower one. For a twohousehold case the Bergsonian SWF is the unspecified function f(U1, U2). The function itself may take any form, and this will depend on the nature of the value judgements used. The Bergsonian SWF satisfies the following three properties: 1. Welfarism, which means that social welfare depends only on the utility levels of the households. 2. The strong Pareto Principle, which means that the social welfare function is increasing in each household’s utility level, ceteris paribus. 3. Convexity, which means that if one household is made better off then another household must be made worse off to maintain the same level of social welfare. The intensity of this trade-off depends on the desirability of inequality in utility across households. The effect of this is that SWFs are convex to the origin (just like indifference curves). Note that SWFs enable us to rank projects even when there are gainers and losers. Three common SWFs are: 3 1. The utilitarian SWF, where social welfare is the equal-weighted sum of household utilities. 2. The generalised utilitarian SWF, where social welfare is the weighted sum of household utilities. 3. The maximin SWF, where social welfare is identified with the utility of the worst-off household. Each of these types of SWF has different informational requirements in terms of the measurability and comparability of households’ utility. We may also combine the social welfare function with the utility possibilities frontier (UPF) that bounds the set of all feasible utility distributions that can be attained for a fixed endowment of goods. The equilibrium point occurs where the highest attainable SWF is tangential to the UPF. This equilibrium is also called the constrained bliss point because it represents the combination of exchange, production and distribution that leads to the maximum attainable social welfare. The bliss point is constrained by the available resources. Social Welfare Functions: comparability and measurability We wish to examine the social welfare orderings (SWOs) that are possible with different informational requirements. SWO possibilities with non-comparability (NC) NC means that none of the information measured for individual household utility can be used when making across-household comparisons so we cannot say whether one household is better off than another in a particular social state. Ordinal scale (OS) measurability OS measurability allows only the ordering or ranking of levels of utility by households (e.g. only statements like “Alice prefers state x to state y” are possible). Dictatorship (strong or lexicographic) is the only possible SWO (proved by the Arrow Possibility Theorem - to be covered in Topic 6 to follow). Cardinal scale (CS) measurability CS measurability gives information on the magnitude of the change in utility in going from one indifference curve to another. Therefore, CS allows the ordering of changes in utility as well as the ordering of levels of utility (e.g. “Alice has an increase in 5 units of utility in going from state x to state y”). However, for CS measurability combined with 4 NC, strong or lexicographic dictatorship is still the only possible SWO (the logic of the Arrow Possibility Theorem is unchanged with the introduction of CS). Ratio scale (RS) measurability RS gives information on the proportionate change in utility in going from one indifference curve to another (e.g. “Alice’s utility doubles in going from x to y). This cannot be combined with NC. No units of utility are now referred to (so there is no problem of non-commensurate utility across households), so proportionate changes must be fully comparable across households. Absolute scale (AS) measurability With AS measurability a unique real number is attached to each indifference curve of the household. This cannot be combined with NC. AS measurability implies full comparability of utility across households. SWO possibilities with full comparability (FC) FC means that all of the information available for the individual household is available for comparisons across households so we can say whether one household is better off than another in a particular social state. In all instances, the strong and lexicographic dictatorship admitted with OS measurability and NC are possible. OS measurability OS measurability means that utility levels only can be compared and ranked by the individual household. The fact that utility levels are comparable across households (FC) means that all households can be ranked by utility position for any social state. This now permits SWO possibilities based on the utility positions of the households. The ability to compare utility levels across households allows positional dictatorships, where the SWO is dictated not by a particular household but by the preferences of a household occupying a particular utility position. A common example is the Rawlsian maximin SWO, where the social welfare function (SWF) is dictated by the preferences of the household in the lowest utility position. According to maximin SWO, if the worst-off household in state x is better off than the worst-off household in state y then state x is preferred. Note that a maximax SWO is also possible (where if the best-off household in state x is better off than the best-off household in state y then state x is preferred), or any dictatorship by the nth well-off person. However, only by adding an additional equity axiom (i.e. determining who the positional dictator should be) does one narrow the positional dictatorship to one specific form. Also possible is the positional lexicographic SWO, where there is a hierarchy of households ranked according to their utility level in some way (though not necessarily going from the worst-off household to the best-off household or vice versa), such that the 5 SWO is dictated by the first household in the hierarchy providing it has a strict preference. If the first household does not have a strict preference (i.e. if it is indifferent), the strict preferences of the second household in the ranking dictate the SWO, etc.. Specific forms of the positional lexicographic SWO are the leximin SWO and the leximax SWO. The leximin SWO is a positional lexicographic SWO where the positional hierarchy runs from the worst-off to the best-off position. For the leximax case the hierarchy runs in the opposite direction. CS measurability CS measurability means that utility levels and increments in utility can both be compared by the individual household. By FC, comparisons can also be made across households. In addition to statements like “Alice has a 5 unit increase in utility in going from state x to state y” (arising from CS measurability) we can also make statements such as “the increment in Alice’s utility is greater than the increment in Bob’s utility”. The planner now has more information, and this increases the possible SWOs. All SWOs arising from OS measurability with FC are available, but now additional SWOs are admitted, specifically those relying on cross-household comparisons of changes in utility. These include the utilitarian SWO, where social welfare is the unweighted sum of household utilities, and the generalised utilitarian SWO, where social welfare is the weighted sum of household utilities. These are admitted because we can now say whether the (weighted) sum of the changes in utility in going from one social state to another is positive or negative (e.g. “is the [weighted] sum of changes greater than, less than or equal to zero?”). This is possible since (a+x)+(b+y)=(a+b)+(x+y). The utilitarian SWOs may be combined with the positional dictatorship (e.g., maximin, maximax, etc.). Generally we have social welfare W given by: W = Wu + (Wd – Wu) Where Wu is the (generalised) utilitarian form, Wd is a positional dictatorship form (maximin, maximax, etc.) and is a scalar between zero and one, representing the importance of the positional dictator’s utility to society’s welfare. The (generalised) utilitarian SWO may also be combined with the positional lexicographic SWO. RS measurability With RS measurability as with OS measurability, utility levels or rankings can be compared by the individual household. Additionally, proportional changes in utility can be compared by the individual household, and (by FC) utility levels and proportional changes in utility can be compared across households. This means that statements such as “the proportional change in Alice’s utility is greater than the proportional change in Bob’s utility” are possible. When utility is measurable on a ratio scale, still further SWOs 6 to those available with OS measurability and FC are possible. These include the Bernouilli-Nash SWO, where social welfare is the unweighted product of household utilities, and the generalised Bernouilli-Nash SWO, where social welfare is the weighted product of household utilities. These are admitted because we can now say whether the (weighted) product of the proportional changes in utility in going from one social state to another is positive or negative (e.g. “is the [weighted] product of changes greater than, less than or equal to one?”). This is possible since ax*by=ab*xy. AS measurability When utility is measured on an absolute scale and FC is assumed, the SWO possibilities are the widest possible. AS measurability and FC therefore permit the Bergsonian SWF, where the social welfare function may take any form. SWO possibilities with partial comparability (PC) PC means that only some of the households’ information is available for comparisons across households. OS measurability OS measurability allows only the ordering or ranking of levels of utility by households. Therefore, there is only one type of information available, so PC is not possible. There may be only NC or FC. CS measurability With CS measurability individual households can make comparisons of both their levels of utility and of increments in their utility. With PC, either levels or rankings of utility only can be compared across households (called level comparability, LC), or only the increments in utility can be compared across households (called increment comparability, IC). With CS measurability and LC we are in exactly the same position as with OS and FC, and therefore positional dictatorships and positional lexicographic SWOs are possible, as well as strong and lexicographic dictatorships admitted with OS measurability and NC. With CS measurability and IC the utilitarian and generalised utilitarian SWOs are possible (as well as strong and lexicographic dictatorships) since they rely only on being able to rank changes (increments) in utility across households. Positional dictatorships and the positional lexicographic SWOs are not possible since they require LC. RS measurability With RS measurability individual households can make comparisons of both their levels of utility and of proportional changes in their own utility. With PC, either levels of utility 7 only can be compared across households (this is LC), or only the proportional changes in utility can be compared across households (called proportion comparability, PrC). With RS measurability no units of utility are now referred to, so proportionate changes must be fully comparable across households (i.e. PrC must be achievable at least). Since PrC is possible, admissible SWOs are the Bernouilli-Nash SWO and generalised Bernouilli-Nash SWO, as well as strong and lexicographic dictatorships. AS measurability With AS measurability a unique real number is attached to each indifference curve of the household. This cannot be combined with PC. AS measurability implies FC across households. 8