The Buildings of the Mycenaeans

advertisement

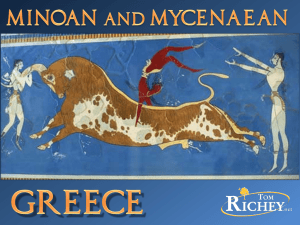

The Buildings of the Mycenaeans The history of man in Greece goes far back in time. Perhaps as early as 6000 B., there were Neolithic settlements. Sometime around 2500 B.C. bronze began to be used by the people living there, beginning a period of history called the Early Helladic or Early Bronze Age. The Early Helladic people refined their techniques in metalwork, particularly in gold, and raised cities girded with walls and towers. Through trade with the Cretans and others in the Aegean they prospered. Then disaster overcame them. Sometime around 2000 B.C. some Indo-European tribes swept down on the Greek peninsula, conquering the Early Helladic people and destroying their cities. Gradually the Mycenaean civilization developed. The period from the Mycenaean conquest to about 1600 B.C. is known as the Middle Helladic or Middle Bronze Age in Greece. From about 1600 to 1100 B.C. a remarkable civilization developed in the period known as the Late Helladic or Late Bronze Age. This civilization spread throughout Greece, around the Aegean westward to Sicily and Italy, and elsewhere in the Mediterranean. A Mycenaean dagger has been found in Cornwall, on the west coast of England, and there is a carving of one of these daggers on the ancient monument at Stonehenge, which is located in southern England. According to existing evidence, it appears that the Mycenaeans spoke the earliest form of what we know as Greek. In 1939, Carl Blegen, an American archaeologist, found 600 clay tablets in a palace at Pylos, a Mycenaean city, on the southwestern coast of Greece. These tablets were written in a script called Linear B, a script which had earlier been discovered on tablets in the Cretan city of Knossos by an Englishman, Sir Arthur Evans. In 1953 two Englishmen, Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, published a work identifying the script as old Greek. Tablets bearing this same script have since turned up in other parts of Greece. About 1100 B.C. the Mycenaeans were overcome by invaders who came by land and possibly also by sea. Historians usually refer to these invaders as Dorians, but their identity is not yet certain. It is known, however, that these new Greeks built a new civilization on the remains of the old, a civilization which continues to have its impact. The following selection describes some of the accomplishments of the Mycenaeans.* * * * * INQUIRY: What conclusions might you draw about the Mycenaean’s from their architecture? * * * * This growing civilization was truly Mycenaean by the middle of the sixteenth century B.C. By then great wealth existed in Greece, and soon after, if not already, palaces and walled citadels rose above towns which had long been settled in important strategic and commercial locations. In the succeeding four hundred years, scores of small and large towns flourished in even the remotest parts of Greece. The remains of many towns show that major works of architecture and large-scale engineering projects were conceived and carried to completion. The later Greeks, the Hellenes, were so staggered by the traces of Mycenaean masonry that they assumed that the walls must have been built by semi-divine giants, the Cyclopes, and the term Cyclopaean survives today to denote the Mycenaean method of building walls with monumental blocks of stone. These walls, parts of which still stand, point to the centers of power all through Greece. At Mycenae, at nearby Tiryns, at Pylos on the west coast of the Peloponnesus, at Thebes in Boeotia, and at Lolkos in Thessaly the Mycenaeans settled and built communities. It seems, from what we know today, that the Mycenaeans established towns in all the places which were to be significant for one reason or another in the later classical period, and in many others besides. In Mycenaean times Greece was probably as heavily settled and prosperous as it ever was to be again, and the general level of culture may have been far higher than the silent stones would ever lead us to assume. The palaces were decorated by magnificent frescoes of great artistic and technical quality… The Mycenaean builder's skills and his mastery of engineering appear again and again in the structures which still stand. When the architects turned to the construction of tombs, they showed their genius in the creation of structures as brilliant as they are different from palaces. The tholos tomb, a large round chamber with a domed roof, is almost a hallmark of Mycenaean civilization. The so-called Treasury of Atreus, an underground tomb outside the citadel of Mycenae and below the lower town, exemplifies the Mycenaean mastery of complex problems in structural engineering. A cement-paved approach, flanked by walls lined with huge well-cut blocks of stones, runs directly into the tomb. A door, capped by an enormous lintel weighing over a hundred tons, opens into the depths of the hill. Above the door, shadowed in black, an open triangular arch relieves the weight of stone pressing down upon it. A short corridor leads to the main chamber, a circular room almost fifty feet in diameter. Its walls, successive courses of smoothly cut stone, rise almost forty-five feet, curving with mathematical exactness to finish in a perfect dome. This masterpiece of precision, built about 1330 B.C., reveals perhaps more clearly than any other single structure the technical accomplishment of the Mycenaean builder. He was no mere piler of stones, but an engineer and architect in every sense of the terms. His control of weight and stress in the construction of the great dome shows a technical mastery which would have done credit even to the Romans. Nor was this tomb an accidental flash of genius. Although it is the largest tomb of its type, other tholos tombs dot the mainland of Greece. The Mycenaeans were capable of reproducing this complex structure again and again, and it might well be supposed that Mycenaean architects were specialists whose professional lives were devoted to building and to training technicians for the future. *Alan E Samuel, THE MYCENEANS IN HISTORY, © 1966. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.