SFAS No. 144

advertisement

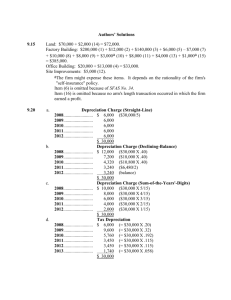

SFAS. No. 144 SFAS No. 144 Accounting for Asset Impairment Guidance on the accounting for asset impairment, using U.S. GAAP, is provided in FASB Statement No. 144, issued in 2001, which addresses the following four questions 8: 1. When should an asset be reviewed for possible impairment? 2. When is an asset impaired? 3. How should an impairment loss be measured? 4. What information should be disclosed about an impairment? 1. When should an asset be reviewed for possible impairment? Conducting an impairment review of every asset at the end of every year would be unlikely to provide sufficiently improved financial information to justify the cost of the reviews. Instead, companies are required to conduct impairment tests whenever there has been a material change in the way an asset is used or in the business environment. In addition, if management obtains information suggesting that the market value of an asset has declined, an impairment review should be conducted. 2. When is an asset impaired? According to the FASB, an entity should recognize an impairment loss only when the undiscounted sum of estimated future cash flows from an asset is less than the book value of the asset. Any recorded goodwill associated with the acquisition of an asset should be added to the book value of the asset in determining whether impairment exists. As illustrated in the following example, this is rather a strange impairment threshold—a more intuitive test would be to compare the book value to the fair value of the asset. Because the undiscounted cash flows do not incorporate the time value of money, the sum of undiscounted future cash flows will always be greater than the fair value of the asset. 3. How should an impairment loss be measured? The impairment loss is the difference between the book value of the asset and the fair value. The fair value can be approximated using the present value of estimated future cash flows from the asset. Any impairment loss amount should first be used to reduce the recorded value of goodwill associated with an asset purchase. Caution! The existence of an impairment loss is determined using undiscounted future cash flows. The amount of the impairment loss is measured using fair value, or discounted, future cash flows. 4. What information should be disclosed about an impairment? Disclosure should include a description of the impaired asset, reasons for the impairment, a description of the measurement assumptions, and the business segment or segments affected. An impairment loss should be included as part of income from continuing operations, and note disclosure of the amount should be made if the impairment loss is not shown as a separate income statement item. Application of the impairment rules is illustrated with the following example. Guangzhou Company purchased a building five years ago for $600,000. The building has been depreciated using the straight-line method with a 20-year useful life and no residual value. Several other buildings in the immediate area have recently been abandoned, and Guangzhou has decided that the building should be evaluated for possible impairment. Guangzhou estimates that the building has a remaining useful life of 15 years, that net cash inflow from the building will be $25,000 per year, and that the fair value of the building is $230,000. Annual depreciation for the building has been $30,000 ($600,000 ÷ 20 years). The current book value of the building is computed as follows: Original cost ............................................................................................................................... $600,000 Accumulated depreciation ($30,000 × 5 years).............................................................................. 150,000 Book value ................................................................................................................................. $450,000 The book value of $450,000 is compared to the $375,000 ($25,000 × 15 years) undiscounted sum of future cash flows to determine whether the building is impaired. The sum of future cash flows is less, so an impairment loss should be recognized. The loss is equal to the $220,000 ($450,000 – $230,000) difference 1 SFAS. No. 144 between the book value of the building and its fair value. The impairment loss would be recorded as follows: Accumulated Depreciation—Building ................................................................................ Loss on Impairment of Building ......................................................................................... Building ($600,000 – $230,000) .............................................................................. 150,000 220,000 370,000 The new recorded value of $230,000 ($600,000 – $370,000) is considered to be the cost of the asset. After an impairment loss is recognized, no restoration of the loss is allowed even if the fair value of the asset recovers. The odd nature of the undiscounted cash flow threshold can be seen if the facts in the Guangzhou example are changed slightly. Assume that net cash inflow from the building will be $35,000 per year, and that the fair value of the building is $330,000. With these numbers, no impairment loss is recognized, even though the fair value of $330,000 is less than the book value of $450,000, because the undiscounted sum of future cash flows of $525,000 ($35,000 × 15 years) exceeds the book value. In many cases, it is more appropriate to estimate a range of possible future cash flows rather than to make a specific point estimate. In the example above, assume that instead of estimating future cash flows of $25,000 per year, it is estimated that the following two cash flow scenarios are possible, with the indicated probabilities: Future Cash Inflows Probability Scenario 1 $20,000 per year for 15 years 85% Scenario 2 $50,000 per year for 15 years 15% In applying the impairment test, the weighted-average undiscounted cash flows are computed as follows: Probability-Weighted Undiscounted Future Cash Inflows Probability Future Cash Flows Scenario 1 $20,000 × 15 years = $300,000 85% $255,000 Scenario 2 $50,000 × 15 years = $750,000 15% 112,500 Total $367,500 The $367,500 probability-weighted sum of undiscounted future cash flows is compared to the $450,000 book value of the building, indicating that the asset is impaired ($367,500 < $450,000). Assume that in this case there is no observable market value of the building and that the market value must be estimated using present value techniques. If the risk-free interest rate is 6.0%, the expected present value is computed as follows: Present Value Future Cash Inflows Probability-Weighted (6.0% discount rate) Probability Present Value Scenario 1 $20,000 × 15 years $194,245 85% $165,108 Scenario 2 $50,000 × 15 years 485,612 15% 72,842 Estimated fair value $237,950 The impairment loss would be recorded as follows: 2 SFAS. No. 144 Accumulated Depreciation—Building ................................................................................ Loss on Impairment of Building ($450,000 - $237,950) ...................................................................... Building ($600,000 – $237,950) .............................................................................. 150,000 212,050 362,050 Classifying an Asset as Held for Sale Often a plan is made to dispose of an asset before the actual sale takes place. Special accounting is required if the following conditions are satisfied: Management commits to a plan to sell a long-term operating asset. The asset is available for immediate sale. An active effort to locate a buyer is underway. It is probable that the sale will be completed within one year. If these criteria are satisfied, two uncommon accounting actions are required. During the interval between being classified as held for sale and actually being sold: 1. no depreciation is to be recognized, and 2. the asset is to be reported at the lower of its book value or its fair value (less the estimated cost to sell). [Footnote: Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 144, “Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets,” Norwalk, CT: Financial Accounting Standards Board, August 2001, par. 34.] To illustrate the accounting for a long-term asset that is classified as held for sale, assume that as of July 1, 2005, Haan Company has a building with a cost of $100,000 and accumulated depreciation of $35,000. Haan commits to a plan to sell the building by March 1, 2006. On July 1, 2005, the building has an estimated fair value of $40,000, and it is estimated that selling costs associated with the disposal of the building will be $3,000. On July 1, 2005, Haan must make the following journal entry: Building -- Held for Sale Loss on Held-for-Sale Classification Accumulated Depreciation -- Building Building 37,000 28,000 35,000 100,000 After this journal entry is made, the building is recorded at its net realizable value of $37,000 ($40,000 selling price - $3,000 selling costs). If the net realizable value had been greater than the book value of $65,000 ($100,000 - $35,000), no journal entry would have been made. This measurement approach is exactly the same as that used to record inventory at the lower of cost or market, as illustrated in Chapter 9. ================= Caution: Recognition of this loss did NOT involve use of the two-step impairment test explained earlier. Instead, the net selling price of the asset held for sale is compared directly to the book value; no comparison is made to the sum of future undiscounted cash flows. ================== On December 31, 2005, no adjusting entry is made for depreciation of the building. As mentioned above, no depreciation expense is recognized on a long-term asset classified as held for sale. The rationale behind this approach is that because the asset is now designated for disposal, the key accounting point is no longer long-term cost allocation using depreciation but is instead proper current valuation of the asset. Accordingly, in the Haan Company example, the $37,000 carrying value of the building on December 31, 2005 would be compared to a revised estimate of the selling price (less selling cost) on that date. If this revised estimate is even lower than $37,000, an additional loss would be recognized. If the estimated net selling price had increased since the initial loss was recognized, a gain would be recognized to the extent of the $28,000 loss initially recognized. For example, if the estimated selling price as of December 31, 2005 was $58,000 (with $3,000 estimated selling costs), the following journal entry would be necessary: 3 SFAS. No. 144 Building Held-for-Sale Gain on Recovery of Value – Held for Sale 18,000 18,000 Computation of gain: ($58,000 - $3,000) - $37,000 = $18,000 A gain is recognized only to the extent that it offsets a previously-recognized loss. For example, if the net selling price of the building on December 31, 2005 was estimated to be $80,000, a gain of only $28,000 would be recognized, instead of the entire indicated gain of $43,000 ($80,000 - $37,000). ================= Caution: This partial recovery of the loss recognized on the held-for-sale classification is NOT the usual practice with impairment losses. For regular long-term assets (not being held for sale), no recovery of impairment losses is allowed. ================== Reporting Discontinued Operations A common below-the-line item involves the disposition of a separately identifiable component of a business either through sale or abandonment. The component of the company disposed of may be a major line of business, a major class of customer, a subsidiary company, or even just a single store with separately identifiable operations and cash flows. The size of the discontinued activity is not the factor that determines whether it is reported as a discontinued operation. Instead, to qualify as discontinued operations for reporting purposes, the operations and cash flows of the component must be clearly distinguishable from other operations and cash flows of the company, both physically and operationally, as well as for financial reporting purposes. For example, closing down one of five product lines in a plant in which the operations and cash flows from all of the product lines are intertwined would not be an example of a discontinued operation. Similarly, shifting production or marketing functions from one location to another would not be classified as a discontinued operation. There are many reasons why management may decide to dispose of a component of a business. For example: • • • • The component may be unprofitable. The component may not fit into the long-range plans for the company. Management may need funds to reduce long-term debt or to expand into other areas. Management may be fearful of a corporate takeover by new investors desiring to gain control of the company. Regardless of the reason for a company’s selling a business component, the discontinuance of a substantial portion of company operations is a significant event. Therefore, information about discontinued operations should be presented explicitly to readers of financial statements. 4 SFAS. No. 144 Reporting requirements for discontinued operations. When a company discontinues operating a component of its business, future comparability requires that all elements that relate to the discontinued operation be identified and separated from continuing operations. Thus, in the Techtronics Corporation income statement illustrated earlier in this chapter, the first category after income from continuing operations is discontinued operations. The category is further separated into two subdivisions: (1) the current-year income or loss from operating the discontinued component, in this case a $35,000 loss, plus any gain or loss on the disposal of the component, in this case a $16,000 loss, and (2) disclosure of the overall income tax impact of the income or loss associated with the component, in this case a tax benefit of $15,300. As previously indicated, the below-the-line items are all reported net of their respective tax effects. If the item is a gain, it is reduced by the tax on the gain. If the item is a loss, it is deductible against other income and thus its existence saves income taxes. The overall company loss can thus be reduced by the tax savings arising from being able to deduct the loss from otherwise taxable income. Frequently the disposal of a business component is initiated during the year but not completed by the end of the fiscal year. To be classified as a discontinued operation for reporting purposes, the ultimate disposal must be expected within one year of the period for which results are being reported. Accordingly, if a company made a decision in 2005 to dispose of a business component in April 2006, then in the 2005 income statement the results of the operations of that business component should be reported as discontinued operations. To illustrate the reporting for discontinued operations, consider the following example. Thom Beard Company has two divisions, A and B. The operations and cash flows of these two divisions are clearly distinguishable from one another, so they both qualify as business components. On June 20, 2005, it is decided to dispose of the assets and liabilities of Division B; it is probable that the disposal will be completed early next year. The revenues and expenses of Thom Beard for 2005 and for the preceding two years are as follows: Sales – A Total Non-Tax Expenses – A Sales – B Total Non-Tax Expenses – B 2005 $10,000 8,800 7,000 7,900 2004 $9,200 8,100 8,100 7,500 2003 $8,500 7,500 9,000 7,700 During the later part of 2005, Thom Beard disposed of a portion of Division B, and recognized a pre-tax loss of $4,000 on the disposal. The income tax rate for Thom Beard Company is 40 percent. The 2005 comparative income statement would appear as follows: 2005 2004 2003 Sales $10,000 $9,200 $8,500 Expenses 8,800 8,100 7,500 Income before Income Taxes $1,200 $1,100 $1,000 Income Tax Expense (40%) 480 440 400 Income from Continuing Operations $ 720 $ 660 $ 600 Discontinued Operations: Income (loss) from operations (including loss on disposal in 2005 of $4,000) (4,900) 600 1,300 Income tax expense (benefit) – 40% (1,960) 240 520 Income (loss) on discontinued operations (2,940) 360 780 Net Income ($2,220) $1,020 $1,380 Notice that this method of reporting allows users to distinguish between the part of Thom Beard’s business that will continue to generate income in the future and the part that will not. This reporting format makes it 5 SFAS. No. 144 much easier for financial statement users to attempt to forecast how Thom Beard will perform in subsequent years. The reporting requirements for discontinued operations are contained in FASB Statement No. 144, “Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets.”13 On the balance sheet, assets and liabilities associated with discontinued components that have not yet been completely disposed of as of the balance sheet date are to be listed separately in the asset and liability sections of the balance sheet. Also, in addition to the summary income or loss number reported in the income statement, the total revenue associated with the discontinued operation should be disclosed in the financial statement notes. The objective of these disclosures is to report information that will assist external users in assessing future cash flows by clearly distinguishing normal recurring earnings patterns from those activities that are not expected to continue in the future and yet are significant in assessing the total results of company operations for the current and prior years. 6