Badger Culling Strategy - Department of Agriculture

advertisement

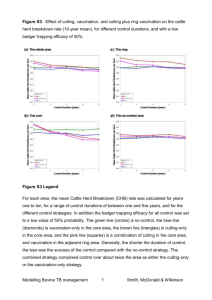

Bovine Tuberculosis Eradication Programme Department’s Wildlife Policy (Badgers) Research conducted over the years by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) and elsewhere has shown that the eradication of Bovine TB is not a practicable proposition in the short to medium-term because of the reservoir of infection in wildlife and, in particular, badgers which is seeding infection into the cattle population. This accords with the recommendation made by Francis(1) speaking of the difficulties in final eradication, that to achieve complete success tuberculosis had to be dealt with in all species. It is also consistent with a statement in December 2011 by the then Minister for the Environment, Agriculture and Rural Affairs in the UK, Mrs Spellman that “no country in the world where wildlife carries TB has successfully controlled the disease in cattle without tackling its presence in wildlife as well”. (2) In Ireland, the first major research project took place in East Offaly between 1989 and 1995. The risk of herd breakdowns in the removal area was significantly reduced, the risk of a TB breakdown in a herd being 14 times higher in the control area compared with the removal area. (3) In addition there was an association between the bovine tuberculosis status and the distance to badger setts. (4) The next significant study was conducted from 1997 to 2002 in four different areas of the country. This study, known as the Four Area Project, involved the intensive and proactive removal of badgers in four “removal” areas and “reactive” culling of badgers in matched reference areas. The published results of this project demonstrated that there was a significant reduction in TB levels in cattle following the removal of badgers. (5) The annual incidence of confirmed herd restrictions was lower in the removal area compared to the reference area in every year of the study period in each of the four counties. (6) In particular, the total number of herd restrictions in the removal areas for the study period was almost 60% lower than in the pre study period. (5) There appears also to be a relationship between breakdown severity and badger removal. When the pre-study and study periods were compared across all four counties, the reduction in the number of major confirmed restrictions was consistently greater than the reduction in all confirmed restrictions. (6) Further studies showed that badger removal in County Laois between 1989 and 2005 and in the Irish midlands during 1989–2004 had a significant beneficial impact on the risk of future breakdowns. Furthermore, these studies found no evidence of a negative impact on the risk of TB in cattle among herds in the surrounding area. (7, 8) Studies at a DNA level demonstrate that badgers and cattle share the same strains of TB (9, 10, 11) and that TB levels in cattle in a locality reflect the level of TB in the local badger population such that so called ‘greenfield’ areas where TB is very low in cattle also have a low TB prevalence in the local badger population. (12) The UK has also conducted significant research into the role of badgers in the spread of TB and the impact of the removal of badgers on the incidence of TB in cattle. The most recent research was conducted by the Independent Scientific Group, which directed the Radomised Badger Culling Trial (RCBT). The initial findings of the trial showed a 19% reduction in the incidence of TB in cattle in the removal areas but a 29% increase in the areas surrounding the removal area, due it was presumed to “perturbation” of the social groupings of badgers in the removal area. However, the effects of the cull continued to be monitored after the cessation of culling and a report by DEFRA in December 2011 stated that “Overall, from the first cull to five years after the last cull (i.e. up to July 2010) there was a 28% relative reduction in TB confirmed cattle herd incidence in the 100 square metres proactively culled areas when compared with the survey-only areas. Confirmed TB herd incidence on the land 2 km outside the culling area was comparable with that in the survey-only areas (9% increase in incidence).” (13) In view of the research in Ireland referred to above, the Bovine TB eradication programme implemented by the Department contains a comprehensive wildlife strategy in order to limit the spread of TB from badgers to cattle. Under this strategy, badgers are captured under licence issued by the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht where they are implicated in an outbreak of TB. Capturing is undertaken only in areas where serious outbreaks of Tuberculosis have been identified in cattle herds and where an epidemiological investigation carried out by the Department’s Veterinary Inspectorate has found that badgers are the likely source of infection. Despite considerable research in both Ireland and the U.K., no test on live badgers has proven efficacious in reliably detecting TB infected badgers and thus culling remains the only method of control currently available. Notwithstanding that in the Regional Red List of Irish mammals, the badger was considered of Least Concern status, and unlikely to become extinct in the foreseeable future(14). In addition, approval to capture a sett is contingent on the total area under capture nationally being maintained below 30% of the agricultural land in the country. In addition, the Irish Wildlife Trust recently submitted a complaint to the Council of Europe about the threat to the badger population posed by the Department’s culling policy. This complaint was rejected by the Council which concluded that: “Although badgers have gone down from around 95,000 in 2000 to around 70,000 at present, numbers are not expected to fall anymore. Those densities are higher than in mainland Europe and the species is not threatened nationally or locally. The policy is to keep population at safe low levels, far from causing the species to be threatened. Research is on-going on vaccines for badgers and trials are starting, which may hopefully provide appropriate alternative solutions to culling.” In order to ensure that the badger culling programme takes place as humanely as possible, the Department continually monitors damage and injury to badgers captured under this programme. Badgers are captured using a specifically designed stoppedbody restraint by trained Farm Relief Service contractors, monitored and supervised by DAFM staff. The restraints used in the capture of badgers are approved under Section 34 of the 1976 Wildlife Act and are specifically designed with a ‘stop’ so as not to tighten beyond a predetermined point and so will not cause death by strangulation(15). All restraints are monitored daily and any badgers are removed within a maximum of 24 hours of capture. A condition of the licence granted is that restraints are checked before noon the next day. Capturing of badgers is not permitted during the months of January, February and March in new capture areas. Research undertaken by Denise Murphy et al(15) at the Centre for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis (CVERA) in UCD has shown that damage/injury to captured badgers is none or minimal while in the stopped restraint and lower than with other capture methodologies. (16) The Department monitors the animal welfare aspects of badger culling on a continuous ongoing basis and is also satisfied that the existing culling arrangements and procedures result in minimal injury to badgers. Nevertheless, the intention is to replace badger culling with vaccination when research demonstrates that this is a practicable proposition. With this in mind, the Department has been collaborating for some years with the Centre for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis (CVERA) in UCD on research into a vaccine to control tuberculosis in badgers and to break the link of infection to cattle. Research to date has demonstrated that oral vaccination of badgers in a captive environment with the BCG vaccine generates high levels of protective immunity against challenge with bovine TB(17). Field trials are also being undertaken, involving the vaccination of several hundred badgers over 3 to 4 years, with continuous monitoring of the population to assess the impact of the vaccine on the incidence of disease in the vaccinated and non-vaccinated control badger populations(18). Success in the field trials will eventually lead to implementation of a vaccination strategy as part of the national TB control programme. However, it will be some years before the benefits of a vaccine can be seen and therefore targeted badger removals will continue in the medium term. The Department is satisfied that the introduction of the badger removal policy has contributed to a significant reduction in the incidence of TB over the past number of years. Herd incidence has fallen from 7.5% in 2000 to 4.2% in 2012. The number of reactors has fallen from approximately 40,000 to 18,430 during the same period. In fact, the incidence of bovine TB in Ireland has been at historically low levels in recent years. Notwithstanding the difficulty in attributing trends to a single factor and the cyclical nature of the disease, the Department is satisfied that the culling of infected badgers, which is underpinned by research studies and sound science, has led to a significant reduction in the incidence of TB in cattle over the past decade. April 2013 References (1) Francis J. 1958. Tuberculosis in animals and man: a study in comparative pathology. Cassell & Co. Ltd. (2) Statement made by UK Environment Secretary of State Caroline Spelman, on 14 December 2011 confirming that the Government is to allow a badger control programme including two pilot badger culls in early autumn 2012 to tackle the spread of bovine TB. (3) Eves, J.A., 1999. Impact of badger removal on bovine tuberculosis in east County Offaly. Ir. Vet. J. 52, 199–203. (4) Martin, S.W., Eves, J.A., Dolan, L.A., Hammond, R.F., Griffin, J.M., Collins, J.D., Shoukri, M.M., 1997. The association between the bovine tuberculosis status of herds in the East Offaly Project Area, and the distance to badger setts, 1988-1993. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 31, 113-125. (5) Griffin, J.M., Williams, D.H., Kelly, G.E., Clegg, T.A., O’Boyle, I., Collins, J.D., More, S.J. 2005. The impact of badger removal on the control of tuberculosis in cattle herds in Ireland. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 67, 237-266. (6) Griffin, J.M., More, S.J., Clegg, T.A., Collins, J.D., O’Boyle, I., Williams, D.H., Kelly, G.E., Costello, E., Sleeman, D.P., O’Shea, F., Duggan, M., Murphy, J., Lavin, D.P.T., 2005. Tuberculosis in cattle: the results of the four-area project. (2005) Irish Veterinary Journal (11) 629-636. (7) Olea-Popelka, F.J., Fitzgerald, P., White, P., McGrath, G., Collins, J.D., O'Keeffe, J., Kelton, D.F., Berke, O., More, S.J., Martin, S.W., 2009. Targeted badger removal and the subsequent risk of bovine tuberculosis in cattle herds in county Laois, Ireland. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 88, 178-184. (8) Kelly, G. E., Condon, J., More, S. J., Dolan, L., Higgins, I., Eves J. 2008, A long- term observational study of the impact of badger removal on herd restrictions due to bovine TB in the Irish midlands during 1989–2004. Epidemiol. Infect. 136, 1362– 1373. (9) Costello, E., O’Grady, D., Flynn O., O'Brien, R., Rogers, M., Quigley, F., Egan, J., Griffin, J. 1999. Study of restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and spoligotyping for epidemiological investigation of Mycobacterium bovis infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 3217–3222. (10) Olea-Popelka, F. J., Flynn, O., Costello E., McGrath, G., Collins, J.D., O'keeffe, J., Kelton, D.F., Berke, O., Martin, S.W. 2005. Spatial relationship between Mycobacterium bovis strains in cattle and badgers in four areas in Ireland,” Preventive Veterinary Medicine, vol. 71, no. 1-2, pp. 57–70. (11) Murphy, C., Costello, E., Murphy, D., Corner, L.A., Gormley, E. 2012. DNA typing of Mycobacterium bovis isolates from badgers (Meles meles) culled from areas in Ireland with different Levels of Tuberculosis prevalence. Veterinary Medicine International Volume 2012, Article ID 742478, 6 pages. doi:10.1155/2012/742478 (12) Murphy, D., Gormley, E., Collins D. M., McGrath, G., Sovsic, E., Costello, E., Corner, L.A. 2011. Tuberculosis in cattle herds are sentinels for Mycobacterium bovis infection in European badgers (Meles meles): the Irish greenfield study. Veterinary Microbiology, vol. 151, no. 1-2, pp. 120–125. The Government’s policy on Bovine TB and Badger Control in England, December 2011 www.defra.gov.uk (13) (14) Marnell, F., Kingston, N. & Looney, D. (2009) Ireland Red List No. 3: Terrestrial Mammals. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. (15) Murphy, D., O’Keeffe, J., Martin, S.W., Gormley, E., Corner, L.A.L., 2009. An assessment of injury to European badgers (Meles meles) due to capture in stopped restraints. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 45, 481-490. (16) Woodroffe R., FJ Bourne, DR Cox, CA Donnelly, G Gettinby, JP McInerney and WI Morrison, 2005. Welfare of badgers (Meles meles) subjected to culling: patterns of trap-related injury Animal Welfare 14: 11–17 (17) Corner, L.A.L., Costello, E., O’Meara, D., Lesellier, S., Aldwell, F.E., Singh, M., Hewinson, R.G., Chambers, M.A., Gormley, E., 2010. Oral vaccination of badgers (Meles meles) with BCG and protective immunity against endobronchial challenge with Mycobacterium bovis. Vaccine 28, 6265-6272 (18) Aznar, I., McGrath, G., Murphy, D., Corner, L.A.L., Gormley, E., Frankena, K., More, S.J.,Martin, W., O’Keeffe, J., De Jong, M.C.M., 2011. Trial design to estimate the effect of vaccination on tuberculosis incidence in badgers Veterinary Microbiology 151, 104-111.