WHAT ARE FOSSILS AND WHAT IS PALEONTOLOGY

advertisement

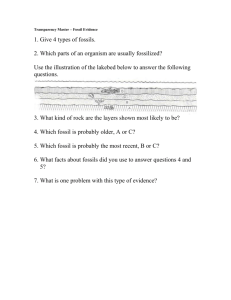

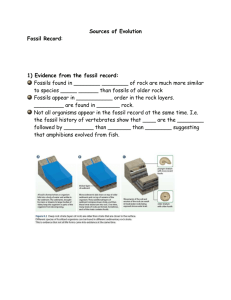

WHAT ARE FOSSILS AND WHAT IS PALEONTOLOGY? The only direct way we have of learning about dinosaurs is by studying fossils. Fossils are the remains of ancient animals and plants, the traces or impressions of living things from past geologic ages, or the traces of their activities. Fossils have been found on every continent on Earth, maybe even near where you live. The word fossil comes from the Latin word fossilis, which means "dug up." Most fossils are excavated from sedimentary rock layers . Sedimentary rock is rock that has formed from sediment, like sand, mud, small pieces of rocks. Over long periods of time, these small pieces of debris are compressed (squeezed) as they are buried under more and more layers of sediment that piles up on top of it. Eventually, they are compressed into sedimentary rock. The layers that are farther down in the Earth are older than the top layers. The fossil of a bone doesn't have any bone in it! A fossilized object has the same shape as the original object, but is chemically more like a rock. Paleontology is the branch of biology that studies the forms of life that existed in former geologic periods, chiefly by studying fossils. What Do Fossils Look Like? Fossils have the same shape that the original item had, but their color, density, and texture vary widely. A fossil's color depends on what minerals formed it. Fossils are usually heavier than the original item since they are formed entirely of minerals (they're essentially stone that has replaced the original structure). Most fossils are made of ordinary rock material, but some are more exotic, including one fossilized dinosaur bone, a Kakuru tibia, which is an opal! HOW FOSSILS FORM Fossils of hard mineral parts (like bones and teeth) were formed as follows: Some animals were quickly buried after their death (by sinking in mud, being buried in a sand storm, etc.). Over time, more and more sediment covered the remains. The parts of the animals that didn't rot (usually the harder parts likes bones and teeth) were encased in the newly-formed sediment. In the right circumstances (no scavengers, quick burial, not much weathering), parts of the animal turned into fossils over time. After a long time, the chemicals in the buried animals' bodies underwent a series of changes. As the bone slowly decayed, water infused with minerals seeped into the bone and replaced the chemicals in the bone with rock-like minerals. The process of fossilization involves the dissolving and replacement of the original minerals in the object with other minerals (and/or permineralization, the filling up of spaces in fossils with minerals, and/or recrystallization in which a mineral crystal changes its form). This process results in a heavy, rock-like copy of the original object - a fossil. The fossil has the same shape as the original object, but is chemically more like a rock! Some of the original hydroxy-apatite (a major bone consitiuent) remains, although it is saturated with silica (rock). Here's a flow chart of fossil formation: There are six ways that organisms can turn into fossils, including: unaltered preservation (like insects or plant parts trapped in amber, a hardened form of tree sap) permineralization=petrification (in which rock-like minerals seep in slowly and replace the original organic tissues with silica, calcite or pyrite, forming a rock-like fossil - can preserve hard and soft parts - most bone and wood fossils are permineralized) replacement (An organism's hard parts dissolve and are replaced by other minerals, like calcite, silica, pyrite, or iron) carbonization=coalification (in which only the carbon remains in the specimen - other elements, like hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are removed) recrystalization (hard parts either revert to more stable minerals or small crystals turn into larger crystals) authigenic preservation (molds and casts of organisms that have been destroyed or dissolved). Most animals did not fossilize; they simply decayed and were lost from the fossil record. Paleontologists estimate that only a small percentage of the dinosaur genera that ever lived have been or will be found as fossils. Most of the dinosaur skeletons that are shown in museums are not actually fossils! They are lightweight fiberglass or resin replicas of the original fossils. Why are Fossils Rock-Colored? Because they ARE rocks! A fossilized object is just a rocky model of an ancient object. A fossil is composed of different materials than the original object was. During the fossilization process, the original atoms are replaced by new minerals, so a fossils doesn't have the same color (or chemical composition) as the original object. Fossils come in many colors and are made of many different types of minerals, depending on what the surrounding rock matrix was composed of; one dinosaur bone (Minmi) is an opal. Also, some fossils of skin (and other soft body parts) have been found. Again, the color of the skin is not retained during the fossilization process, all that remains today is a rocky model of the original. TYPES OF FOSSILS AND WHAT THEY TELL US ABOUT THE DINOSAURS Fossils can be divided into two categories, fossilized body parts (bones, claws, teeth, skin, embryos, etc.) and fossilized traces, called ichnofossils (which are footprints, nests, dung, toothmarks, etc.), that record the movements and behaviors of the dinosaurs. The four types of fossils are: mold fossils (a fossilized impression made in the substrate - a negative image of the organism) cast fossils (formed when a mold is filled in) trace fossils = ichnofossils (fossilized nests, gastroliths, burrows, footprints, etc.) true form fossils (fossils of the actual animal or animal part). There are six ways that organisms can turn into fossils, including: unaltered preservation (like insects or plant parts trapped in amber, a hardened form of tree sap) permineralization=petrification (in which rock-like minerals seep in slowly and replace the original organic tissues with silica, calcite or pyrite, forming a rock-like fossil - can preserve hard and soft parts - most bone and wood fossils are permineralized) replacement (An organism's hard parts dissolve and are replaced by other minerals, like calcite, silica, pyrite, or iron) carbonization=coalification (in which only the carbon remains in the specimen - other elements, like hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are removed) recrystalization (hard parts either revert to more stable minerals or small crystals turn into larger crystals) authigenic preservation (molds and casts of organisms that have been destroyed or dissolved). BODY FOSSILS The most common body fossils found are from the hard parts of the body, including bones, claws and teeth. More rarely, fossils have been found of softer body tissues. Body fossils include: Bones - these fossils are the main means of learning about dinosaurs. The fossilized bones of a tremendous number of species of dinosaurs have been found since 1818, when the first dinosaur bone was discovered. The first nearly-complete skeleton (of Hadrosaurus foulkii) was found in 1858 in New Jersey, USA. Teeth and Claws - Sometimes a bit of a broken tooth of a carnivore is found with another dinosaur's bones, especially those of herbivores. Lots of fossilized teeth have been found, including those of Albertosaurus and Iguanodon . Eggs , Embryos , and Nests - Fossilized dinosaur eggs were first found in France in 1869. Many fossilized dinosaur eggs have been found, at over 200 sites. Sometimes they have preserved parts of embryos, which can help to match an egg with a species of dinosaur. The embryo also sheds light on dinosaur development. The nests and clutches of eggs tells much about dinosaurs' nurturing behavior. A dinosaur egg was found by a 3-year-old child. Skin - Some dinosaurs had thick, bumpy skin, like that of an alligator . A 12-year-old girl discovered a T. rex's bumpy skin imprint, confirming that it had a "lightly pebbled skin." Muscles, Tendons, Organs, and Blood Vessels - These are extremely rare because these soft tissues usually decay before fossilization takes place. Recently, a beautiful theropod fossil, Scipionyx, was found with many impressions of soft tissue preserved. Also rare are so-called dinosaur "mummies", fossilized imprints of dinosaur skin and other features. These are not real mummies in which actual animal tissue is preserved, but fossils that look a bit like mummies. TRACE FOSSILS Trace fossils (ichnofossils) record the movements and behaviors of the dinosaurs. There are many types of trace fossils. Even the lack of trace fossils can yield information; the lack of tail-furrow fossils indicates an erect tail stance for dinosaurs that were previously believed to have dragged their tails. Trackways (sets of footprints) Dinosaur tracks, usually made in mud or fine sand, have been found at over 1500 sites, including quarries, coal mines, A Hadrosaur footprint. riverbeds, deserts, and mountains. There are so many of these fossils because each dinosaur made many tracks (but had only one skeleton) and because tracks fossilize well. Fossil footprints have yielded information about: o Speed and length of stride o whether they walked on two or four legs o o o o the bone structure of the foot stalking behavior (a carnivore hunting a herd of herbivores) the existence of dinosaur herds and stampedes how the tail is carried (few tail tracks have been found, so tails were probably held above the ground) Unfortunately, linking a set of tracks with a particular species is often virtually impossible. Although there were many more plant-eating dinosaurs (sauropods and ornithopods) than meat-eating dinosaurs (theropods), many more footprints of meat-eaters have been found. This may be because the meat-eaters walked in muddy areas (where fottprints are more likely to leave a good impression and fossilize) more frequently than the planteaters). Toothmarks - Toothmarks generally appear in bones . Gizzard Rocks - Some dinosaurs swallowed stones to help grind their food (modern birds do this also). These stones, called gastroliths (literally meaning stomach-stones), have been found as fossils. They are usually smooth, polished, and rounded (and hard to distinguish from river rocks.) Coprolites (fossilized feces) - Coprolites yield information about the dinosaurs' diet and habitats. Coprolites up to 40 cm (16 inches) in diameter have been found, probably from a sauropod, considering its size. A huge theropod coprolite was recently found Sasketchewan, Canada. The only meat-eater large enough in that area at that time was Tyrannosaurus rex. Burrows and Nests - Fossils of dinosaurs' burrows and nests can reveal a lot about their behavior. FINDING FOSSILS: SKILL, TENACITY, AND LUCK Since fossils are buried during their formation, finding them can be difficult. Paleontologists do a lot of research to decide where to dig . To choose an optimal location for a dig, they choose: for dinosaurs sedimentary rock - shale, sandstone, or limestone (this is where most fossils were preserved), a sedimentary layer from the Mesozoic Era (when the dinosaurs lived). Exposed sedimentary rock is pretty easy to identify - it's in layers. To find an example of exposed sedimentary rock in your area, look at the cut-out area where highways go through hills. The layers should be easily visible. Other places to look are cliffs, rock outcroppings, canyons, badlands, etc., a place that was not an ocean or lake during the Mesozoic, because the dinosaurs lived only on land. Areas where fossil-bearing sedimentary rock erode quickly (because of rain, flooding, wind, etc.) are good for finding fossils. Rarely, fossils are observed just sticking out of the ground. More often, paleontologists must do enormous amounts of work to find, excavate , and prepare fossils. The Continents Fossils have been found on every continent on Earth . Rock strata in many places are remarkably similar to each other. This lends credence to the continental drift theory of Alfred Wegener (1912) who theorized that 200 million years ago there was a single land mass on Earth which he called "Pangaea" (meaning "All Earth"). This land mass then slowly drifted apart on Earth's floating crust, forming separate continents. Wegener's theory explains why fossils of the same species are found on many different, unconnected continents. Children and Fossils Children have found important dinosaur fossils, including T. rex found by a 12-year-old and an egg found by a 3-year-old. Fossil Hot Spots: Lagerstätten Lagerstätten (meaning "fossil deposit places" in German) are geological skin deposits that are rich with varied, well-preserved fossils, representing a wide variety of life from a particular era. These spectacular fossil deposits represent an amazing "snapshot" in time. Some Lagerstätten include the La Brea Tar Pits (California, USA), Ediacara Hills (South Australia), Burgess Shale (B.C., Canada), Solnhofen (Germany), and Mazon Creek (Illinois, USA) DATING FOSSILS Dating individual fossils is a relatively straightforward (and approximate) process, outlined below. After that comes a more difficult process: estimating the existence-span of an species. Finding a fossil merely places one organism within a time span. Finding many organisms places the group within a time span. Determining the actual existence-span of the species is very approximate. If the fossils are relatively rare, the actual existence-span may be much greater that the fossil record indicates. Even if the fossils are relatively abundant during the species' heyday, the number of organisms may have been small during the time of its appearance on Earth and during its demise. At these important times, its fossil record might be sparse or nil, causing those times to be underrepresented. DATING INDIVIDUAL FOSSILS Paleontologists use many ways of dating individual fossils in geologic time. 1. The oldest method is stratigraphy, studying how deeply a fossil is buried. Dinosaur fossils are usually found in sedimentary rock. Sedimentary rock layers (strata) are formed episodically as earth is deposited horizontally over time. Newer layers are formed on top of older layers, pressurizing them into rocks. Paleontologists can estimate the amount of time that has passed since the stratum containing the fossil was formed. Generally, deeper rocks and fossils are older than those found above them. 2. Observations of the fluctuations of the Earth's magnetic field, which leaves different magnetic fields in rocks from different geological eras. 3. Dating a fossil in terms of approximately how many years old it is can be possible using radioisotope-dating of igneous rocks found near the fossil. Unstable radioactive isotopes of elements, such as Uranium-235, decay at constant, known rates over time (its half-life, which is over 700 million years). An accurate estimate of the rock's age can be determined by examining the ratios of the remaining radioactive element and its daughters. For example, when lava cools, it has no lead content but it does contain some radioactive Uranium (U-235). Over time, the unstable radioactive Uranium decays into its daughter, Lead-207, at a constant, known rate (its half-life). By comparing the relative proportion of Uranium-235 and Lead-207, the age of the igneous rock can be determined. Potassium-40 (which decays to argon-40) is also used to date fossils. The half-life of carbon-14 is 5,568 years. That means that half of the C14 decays (into nitrogen-14) in 5,568 years. Half of the remaining C-14 decays in the next 5,568 years, etc. This is too short a half-life to date dinosaurs; C-14 dating is useful for dating items up to about 50,000 60,000 years ago (useful for dating organiams like Neanderthal man and ice age animals). Radioisotope dating cannot be used directly on fossils since they don't contain the unstable radioactive isotopes used in the dating process. To determine a fossil's age, igneous layers (volcanic rock) beneath the fossil (predating the fossil) and above it (representing a time after the dinosaur's existence) are dated, resulting in a time-range for the dinosaur's life. Thus, dinosaurs are dated with respect to volcanic eruptions. 4. Looking for index fossils - Certain common fossils are important in determining ancient biological history. These fossil are widely distributed around the Earth but limited in time span. Examples of index fossils include brachiopods (which appeared in the Cambrian period), trilobites (which probably originated in the pre-Cambrian or early Paleozoic and are common throughout the Paleozoic layer - about half of Paleozoic fossils are trilobites), ammonites (from the Triassic and Jurassic periods, and went extinct during the K-T extinction), many nanofossils (microscopic fossils from various eras which are widely distributed, abundant, and time-specific), etc. Excavating Fossils After being found, a fossil must be carefully freed from the rocky matrix that encased it for millions of years without damaging it. First the fossils should be labelled and photographed (while still encased in the rock). Its position should be carefully noted. Most of the overlying rock (the overburden) is removed using large tools (like picks and shovels), but the 2-3 inches (5-8 cm) of rock closest to the fossil are removed with smaller hand tools (like trowels, hammers, whisks, and dental tools). The exposed fossil is photographed and labeled again. Frequently, only some of the overlying rock is removed at the dig site. The rest of the overburden can be removed later, in the lab. Small fossils are easily excavated with small hand tools. Large fossils require more effort and bigger tools in order to expose the specimen; these tools include shovels, picks, jack-hammers, or even explosives. Small and large fossils are excavated differently, but both have to be treated very carefully to avoid breaking them. Before removing a crumbling or fragile fossil, a quick-setting glue can be applied to it (with a brush or sprayer). Then the fossil can be removed from the surrounding rock. The fossil must be packed very carefully to be moved to the lab. Small fossils can be packed in boxes or bags. Large fossils can be first wrapped in paper or burlap, with a layer of plaster applied (like setting a broken bone). First Dinosaur Fossil Discoveries Go to a printable version of this page The first 3 dinosaur fossils led to the recognition of a new group of animals, the dinosaurs. The first nearly-complete dinosaur skeleton in New Jersey spurs modern paleontology. People have been finding dinosaur fossils for hundreds of years, probably even thousands of years. The Greeks and Romans may have found fossils, giving rise to their many ogre and griffin legends. There are references to "dragon" bones found in Wucheng, Sichuan, China (written by Chang Qu) over 2,000 years ago; these were probably dinosaur fossils. Much later, in 1676, a huge thigh bone (femur) was found in England by Reverend Plot. It was thought that the bone belonged to a "giant," but was probably from a dinosaur. A report of this find was published by R. Brookes in 1763. The First Dinosaur Fossil Scientifically Described The first dinosaur to be described scientifically was Megalosaurus. This genus was named in 1824, by William Buckland; Gideon Mantell (not Ferdinand August von Ritgen) assigned the scientific type species name, Megalosaurus bucklandii. Buckland (1784-1856) was a British fossil hunter and clergyman who discovered collected fossils. (Note: the first dinosaur found was Iguanodon, but it was named and described later than Megalodon.) It was the first dinosaur ever described scientifically and first theropod dinosaur discovered (this is all in hindsight, because the dinosaurs had not yet been recognized as a separate taxonomic group - the word dinosaur hadn't even been invented yet). The first dinosaur models (life size and made of concrete) were made by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins of England in 1854. The first dinosaur used for amusement was a life-size model of an Iguanodon (made by Hawkins) that was used to house a dinner party for scientists (including Richard Owen) at a major exhibition. The invitations to the party were sent on fake pterodactyl wings. The party took place in London, England, in 1854 Other Early Dinosaur Finds Gideon A. Mantell (1790-1852) was another early British fossil hunter. He described and named Iguanodon, a duck-billed plant-eater (1825); Iguanodon's teeth and a few bones were found in 1822, perhaps by his wife, IGUANODON Mrs. Mary Mantell in Sussex, (southern) HYLAEOSAURUS England. Gideon Mantell also named Hylaeosaurus, an armored plant-eater (1833) , and others. The Name "Dinosauria" Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892) was a pioneering British comparative anatomist who coined the term dinosauria (from the Greek "deinos" meaning fearfully great, and "sauros" meaning lizard), recognizing them as a suborder of large, extinct reptiles in 1842. He had noticed that a group of fossils (which included remains of Megalosaurus, Iguanodon, and Hylaeosaurus) had certain characteristics in common, including: Column-like legs (instead of the sprawling legs reptiles have) Five fused vertebrae fused to the pelvic girdle. that other Owen presented dinosaurs as a separate taxonomic group in order to bolster his arguments against the newly proposed theory of evolution (although Darwin's "Origin of the Species" wasn't published until 1859, the basic ideas of evolution were known, but its mechanisms, including natural selection, were not). Ironically, his work actually helped support the evolutionists arguments. This new taxonomic name, Dinosauria, and new group of reptiles was only the beginning of a great scientific exploration. Since Owen's time, about 330 dinosaur genera have been described. Every few months (sometimes every few weeks), a new species is unearthed (for recent finds, see Dino News). Paleontologists have varying estimates of how many dinosaur genera existed during the Mesozoic Era; estimates range from about 1,000 to over 10,000. Whatever this number really is, there are a lot of new dinosaurs left to discover! The First Nearly-Complete Dinosaur Skeleton and First American Dinosaur The first dinosaur fossil found in the US was a thigh bone found by Dr. Caspar Wistar, in Gloucester County, New Jersey, in 1787 (it has since been lost, but more fossils were later found in the area). In 1800 in Massachusetts, USA, Pliny Moody found 1foot (31 cm) long fossilized footprints at his farm that were thought by Harvard and Yale scholars to be from "Noah's Raven." Many other dinosaur footprints were been found in New England stone quarries in the early 1800's, but they were thought to be unimportant and A Hadrosaur footprint. were blown up in the quarrying process. Other fragmentary dinosaur bones and tracks were unearthed at this time in Connecticut Valley, Massachusetts. The first nearly-complete dinosaur skeleton was discovered by William Parker Foulke. Foulke had heard of a discovery made by workmen in a Cretaceous marl (a crumbly type of soil) pit on the John E. Hopkins farm in Haddonfield, New Jersey beginning in 1838. Foulke heard of the discovery and recognized its importance in 1858. Unfortunately, some of the bones had already been removed by workmen. The skull-less dinosaur was excavated and named by US anatomist Joseph Leidy who named it Hadrosaurus fouki (meaning "Foulke's big lizard"). It was a duck-billed dinosaur (but it is now a doubtful genus because there is so little fossil information about it). The "Haddonfield Hadrosaurus" is on display at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. Leidy's analysis of this Hadrosaur skeleton was thorough; from its anatomy, he wrote imaginitively about the dinosaur's way of life and its death. Leidy wrote, "Hadrosaurus was most probably amphibious; and though its remains were obtained from a marine deposit, the rarity of them in the latter leads us to suppose that those in our possession had been carried down the current of a river, upon whose banks the animals lived." (Quoted from J. Leidy, Account of the Remains of a Fossil Reptile Recently Discovered at Haddonfield, New Jersey. Proceedings Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Dec. 14, 1858 pp.1-16.) This study influenced the popular image of dinosaurs and dinosaur science for years. This beautiful skeleton made dinosaurs come to life in peoples' imaginations and spurred generations of paleontologists. Taken from Encarta 2008