Supplementary Box 1 | Examples of barriers to effective care for the

advertisement

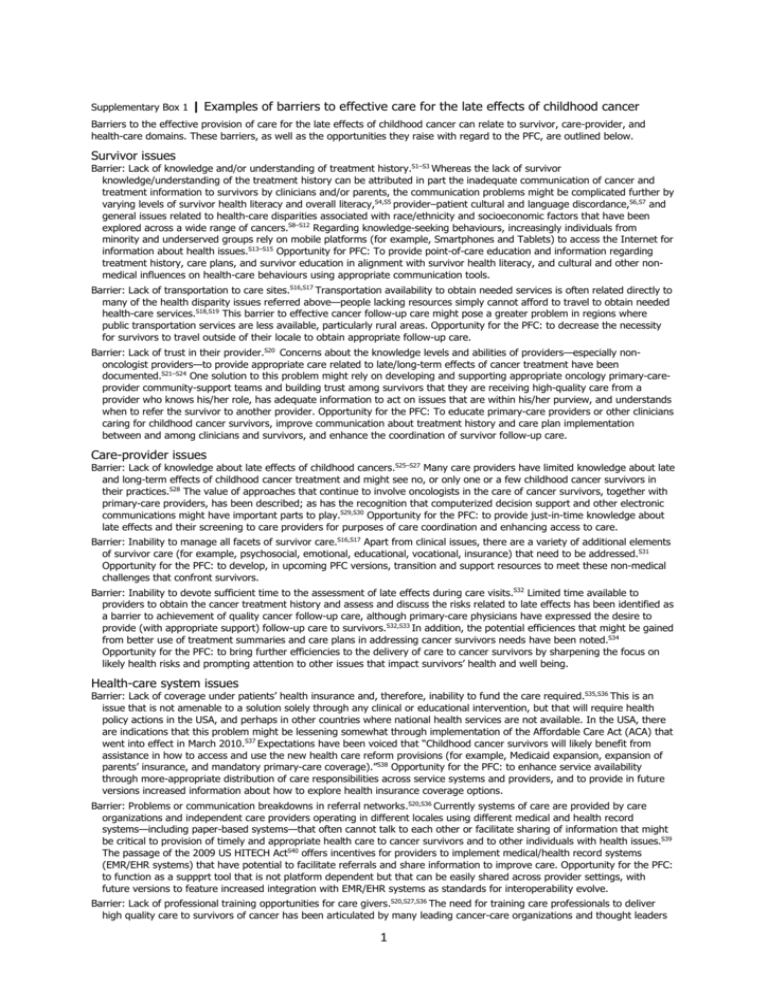

Supplementary Box 1 | Examples of barriers to effective care for the late effects of childhood cancer Barriers to the effective provision of care for the late effects of childhood cancer can relate to survivor, care-provider, and health-care domains. These barriers, as well as the opportunities they raise with regard to the PFC, are outlined below. Survivor issues Barrier: Lack of knowledge and/or understanding of treatment history.S1–S3 Whereas the lack of survivor knowledge/understanding of the treatment history can be attributed in part the inadequate communication of cancer and treatment information to survivors by clinicians and/or parents, the communication problems might be complicated further by varying levels of survivor health literacy and overall literacy,S4,S5 provider–patient cultural and language discordance,S6,S7 and general issues related to health-care disparities associated with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors that have been explored across a wide range of cancers.S8–S12 Regarding knowledge-seeking behaviours, increasingly individuals from minority and underserved groups rely on mobile platforms (for example, Smartphones and Tablets) to access the Internet for information about health issues.S13–S15 Opportunity for PFC: To provide point-of-care education and information regarding treatment history, care plans, and survivor education in alignment with survivor health literacy, and cultural and other nonmedical influences on health-care behaviours using appropriate communication tools. Barrier: Lack of transportation to care sites.S16,S17 Transportation availability to obtain needed services is often related directly to many of the health disparity issues referred above—people lacking resources simply cannot afford to travel to obtain needed health-care services.S18,S19 This barrier to effective cancer follow-up care might pose a greater problem in regions where public transportation services are less available, particularly rural areas. Opportunity for the PFC: to decrease the necessity for survivors to travel outside of their locale to obtain appropriate follow-up care. Barrier: Lack of trust in their provider.S20 Concerns about the knowledge levels and abilities of providers—especially nononcologist providers—to provide appropriate care related to late/long-term effects of cancer treatment have been documented.S21–S24 One solution to this problem might rely on developing and supporting appropriate oncology primary-careprovider community-support teams and building trust among survivors that they are receiving high-quality care from a provider who knows his/her role, has adequate information to act on issues that are within his/her purview, and understands when to refer the survivor to another provider. Opportunity for the PFC: To educate primary-care providers or other clinicians caring for childhood cancer survivors, improve communication about treatment history and care plan implementation between and among clinicians and survivors, and enhance the coordination of survivor follow-up care. Care-provider issues Barrier: Lack of knowledge about late effects of childhood cancers.S25–S27 Many care providers have limited knowledge about late and long-term effects of childhood cancer treatment and might see no, or only one or a few childhood cancer survivors in their practices.S28 The value of approaches that continue to involve oncologists in the care of cancer survivors, together with primary-care providers, has been described; as has the recognition that computerized decision support and other electronic communications might have important parts to play.S29,S30 Opportunity for the PFC: to provide just-in-time knowledge about late effects and their screening to care providers for purposes of care coordination and enhancing access to care. Barrier: Inability to manage all facets of survivor care.S16,S17 Apart from clinical issues, there are a variety of additional elements of survivor care (for example, psychosocial, emotional, educational, vocational, insurance) that need to be addressed.S31 Opportunity for the PFC: to develop, in upcoming PFC versions, transition and support resources to meet these non-medical challenges that confront survivors. Barrier: Inability to devote sufficient time to the assessment of late effects during care visits.S32 Limited time available to providers to obtain the cancer treatment history and assess and discuss the risks related to late effects has been identified as a barrier to achievement of quality cancer follow-up care, although primary-care physicians have expressed the desire to provide (with appropriate support) follow-up care to survivors.S32,S33 In addition, the potential efficiences that might be gained from better use of treatment summaries and care plans in addressing cancer survivors needs have been noted.S34 Opportunity for the PFC: to bring further efficiencies to the delivery of care to cancer survivors by sharpening the focus on likely health risks and prompting attention to other issues that impact survivors’ health and well being. Health-care system issues Barrier: Lack of coverage under patients’ health insurance and, therefore, inability to fund the care required.S35,S36 This is an issue that is not amenable to a solution solely through any clinical or educational intervention, but that will require health policy actions in the USA, and perhaps in other countries where national health services are not available. In the USA, there are indications that this problem might be lessening somewhat through implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that went into effect in March 2010.S37 Expectations have been voiced that “Childhood cancer survivors will likely benefit from assistance in how to access and use the new health care reform provisions (for example, Medicaid expansion, expansion of parents’ insurance, and mandatory primary-care coverage).”S38 Opportunity for the PFC: to enhance service availability through more-appropriate distribution of care responsibilities across service systems and providers, and to provide in future versions increased information about how to explore health insurance coverage options. Barrier: Problems or communication breakdowns in referral networks.S20,S36 Currently systems of care are provided by care organizations and independent care providers operating in different locales using different medical and health record systems—including paper-based systems—that often cannot talk to each other or facilitate sharing of information that might be critical to provision of timely and appropriate health care to cancer survivors and to other individuals with health issues.S39 The passage of the 2009 US HITECH ActS40 offers incentives for providers to implement medical/health record systems (EMR/EHR systems) that have potential to facilitate referrals and share information to improve care. Opportunity for the PFC: to function as a suppprt tool that is not platform dependent but that can be easily shared across provider settings, with future versions to feature increased integration with EMR/EHR systems as standards for interoperability evolve. Barrier: Lack of professional training opportunities for care givers.S20,S27,S36 The need for training care professionals to deliver high quality care to survivors of cancer has been articulated by many leading cancer-care organizations and thought leaders 1 in the clinical care community.S20,S41–S43 Opportunity for the PFC: to extend its reach as a “just-in-time” learning resource to primary care and specialty care providers, as well as non-professional caregivers, faced with the challenges posed in providing follow-up care to childhood cancer survivors. Abbreviations: EMR/EHR, electronic medical record/electronic health record; HITECH, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health; PFC, Passport for Care. S1. Kadan-Lottick, N. S. et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 287, 1832–1839 (2002). S2. Bashore, L. Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors’ knowledge of their disease and effects of treatment. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 21, 98–102 (2004). S3. Caprino, D., Wiley, T. J. & Massimo, L. Childhood cancer survivors in the dark. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 2748–2750 (2004). S4. Davis, T. C., Williams, M. V., Marin, E., Parker, R. M. & Glass, J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J. Clin. 52, 134–149 (2002). S5. Pollack, L. A., Hawkins, N. A., Peaker, B. L., Buchanan, N. & Risendal, B. C. Dissemination and translation: a frontier for cancer survivorship research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 20, 2093–2098 (2011). S6. Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E. & Ananeh-Firempong, O. 2nd. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 118, 293–302 (2003). S7. Beckjord, E. B. et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J. Cancer Surviv. 2, 179–189 (2008). S8. Bigby, J. & Holmes, M. D. Disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Cancer Causes Control 16, 35–44 (2005). S9. Gilligan, T. Social disparities and prostate cancer: mapping the gaps in our knowledge. Cancer Causes Control 16, 45–53 (2005). S10. Palmer, R. C. & Schneider, E. C. Social disparities across the continuum of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control 16, 55–61 (2005). S11. Newmann, S. J. & Garner, E. O. Social inequities along the cervical cancer continuum: a structured review. Cancer Causes Control 16, 63–70 (2005). S12. Weissman, J. S. & Schneider, E. C. Social disparities in cancer: lessons from a multidisciplinary workshop. Cancer Causes Control 16, 71–74 (2005). S13. Chou, W. Y., Liu, B., Post, S. & Hesse, B. Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2008. J. Cancer Surviv. 5, 263–270 (2011). S14. Laz, T. H. & Berenson, A. B. Racial and ethnic disparities in internet use for seeking health information among young women. J. Health Commun. 18, 250–260 (2012). S15. Viswanath, K. et al. Internet use, browsing, and the urban poor: implications for cancer control. J. Natl Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2013, 199–205 (2013). S16. Eshelman-Kent, D. et al. Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. J. Cancer Surviv. 5, 345–357 (2011). S17. Freyer, D. R. Transition of care for young adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: rationale and approaches. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4810–4818 (2010). S18. Kim, P. Cost of cancer care: the patient perspective. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 228–232 (2007). S19. Siminoff, L. A. & Ross, L. Access and equity to cancer care in the USA: a review and assessment. Postgrad. Med. J. 81, 674–679 (2005). S20. Freyer, D. R. & Brugieres, L. Adolescent and young adult oncology: transition of care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 50, 1116–1119 (2008). S21. Baravelli, C. et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J. Cancer Surviv. 3, 99–108 (2009). S22. Bober, S. L. et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer 115, 4409– 4418 (2009). S23. Nissen, M. J. et al. Views of primary care providers on follow-up care of cancer patients. Fam. Med. 39, 477–482 (2007). S24. Potosky, A. et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 1403–1410 (2011). S25. Henderson, T. O., Friedman, D. L. & Meadows, A. T. Childhood cancer survivors: transition to adultfocused risk-based care. Pediatrics 126, 129–136 (2010). S26. Henderson, T. O., Hlubocky, F. J., Wroblewski, K. E., Diller, L. & Daugherty, C. K. Physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of childhood cancer survivors: a mailed survey of pediatric oncologists. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 878–883 (2010). S27. Suh, E. et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 160, 11–17 (2014). S28. Oeffinger, K. C. Childhood cancer survivors and primary care physicians. J. Fam. Pract. 49, 689–690 (2000). S29. Grunfeld, E. Primary care physicians and oncologists are players on the same team. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 2 2246–2247 (2008). S30. Grunfeld, E. & Earle, C. C. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: treatment through survivorship. J. Natl Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 25–30 (2010). S31. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hematology/Oncology & Children’s Oncology Group. Longterm follow-up care for pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatrics 123, 906–915 (2009). S32. Sima, J. L., Perkins, S. M. & Haggstrom, D. A. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 36, 118–124 (2014). S33. Del Giudice, M. E., Grunfeld, E., Harvey, B. J., Piliotis, E. & Verma, S. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3338–3345 (2009). S34. Ganz, P. A. Monitoring the physical health of cancer survivors: a survivorship-focused medical history. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 5105–5111 (2006). S35. Keegan, T. H. et al. Medical care in adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: what are the biggest access-related barriers? J. Cancer Surviv. 8, 282–292 (2014). S36. Robison, L. L. & Hudson, M. M. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 61–70 (2014). S37. US Government Printing Office. Public Law 111–148: The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [online], http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf (2010). S38. Park, E. R. et al. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants’ perceptions and knowledge of health insurance coverage: implications for the Affordable Care Act. J. Cancer Surviv. 6, 251–259 (2012). S39. Brailer, D. J. Interoperability: the key to the future health care system. Health Aff. (Millwood) Suppl. Web Exclusives: W5-19–W5–21 (2005). S40. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HITECH Act [online], http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/hitech-act-0 (2013). S41. McCabe, M. S. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 631–640 (2013). S42. Chubak, J. et al. Providing care for cancer survivors in integrated health care delivery systems: practices, challenges, and research opportunities. J. Oncol. Pract. 8, 184–189 (2012). S43. Forsythe, L. P. et al. Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: associations with survivorship care. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 105, 1579–1587 (2013). 3