Witnesses of Sexual Harassment

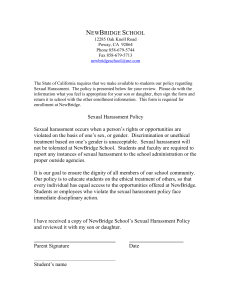

advertisement