Review of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Structural Adjustment

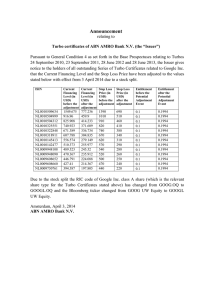

advertisement