rivest adversaries

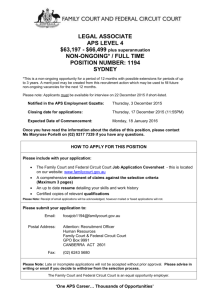

advertisement