Reinventing the Hong Kong Civil Service:

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND BEHAVIOR,

9 (2), 212-234 SUMMER 2006

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: SAME NPM REFORM,

DIFFERENT CONTEXTS AND POLITICS

Anthony B. L. Cheung*

ABSTRACT. Hong Kong’s public sector reform since the 1990s is not just a continuation of an administrative reform trajectory started in colonial years to modernize the civil service. Although concerns for efficiency, productivity and value for money have always formed part of the reform agenda at different times, an efficiency discourse of reform is insufficient for capturing the full dynamics of institutional change whether in the pre-1997 or post-1997 period. During Hong Kong’s political transition towards becoming an SAR of China in 1997, public sector reform helped to shore up the legitimacy of the bureaucracy. After 1997, new political crises and the changing relations between the Chief Executive and senior civil servants have induced the advent of a new “public service bargain” which gives different meaning to the same NPM-like measures.

I NTRODUCTION

Since the early 1990s, the previous Hong Kong colonial government had been pursuing public sector reform in the name of efficiency improvement (Finance Branch, 1989; Cheung, 1996a).

Major reform measures included: budgetary devolution and the setting up of self-accounting trading funds; privatization, contracting out, and outsourcing; streamlining of policy management through the strengthening of central policy agencies known as “policy branches;” 1 promotion of customer orientation, performance pledges, and a management-for-results culture within the civil service; and decentralization of financial and human resource management.

---------------------------

* Anthony B. L. Cheung, Ph.D., is Professor of the Department of Public and

Social Administration, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. He writes extensively on privatization, public sector reforms, Hong Kong politics and Asian administrative reforms.

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS

Copyright © 2006 by PrAcademics Press

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 213

In the post-handover period since July 1997 when Hong Kong reverted to Chinese sovereignty, the new special administrative region (SAR) government launched a high-profile civil service reform and an “enhanced productivity program” in 1999 to improve performance and reduce public sector cost. A new executive accountability system was introduced in 2002 by turning the top-tier principal officials, previously civil servants, into political appointments

(Burns, 2002). Meanwhile civil service pay reform has been put on the agenda (Cheung, 2004).

There are at least two ready ways of conceptualizing these reforms of the public sector. The new initiatives and measures can be considered within Hong Kong’s longstanding trajectory of administrative reform since the 1970s to modernize its public service and to shore up the capacity to deliver of its administrative state.

Given the emergence of a world-wide movement of public sector reform in the 1990s, similar reform in Hong Kong can also be construed as a response to (or convergence with) such a global trend and an attempt to improve efficiency of the public service through adopting “new public management” (NPM) methods (Hood, 1991;

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1995).

Both the “modernization” and “convergence” perspectives only see reform as a reinvention of the public service in order to enhance its managerial effectiveness, in other words, within an efficiency discourse. They, as this article argues, cannot fully capture the dynamics of reform during the political transition years of Hong Kong before and after 1997. The efficiency discourse was at best the rhetoric of public sector reform which actually underscored a legitimation discourse within the unique context of pre-handover

Hong Kong when the departing colonial administration had to confront multifarious political challenges (Cheung, 1996a). In the name of improving managerial competence, public sector reform also served the purpose of re-legitimating public bureaucratic power to cope with political change (Cheung, 1996b). Such an attempt at an administrative answer to a political problem was not without precedent in colonial Hong Kong’s administrative history (Cheung,

1999), it constituted part of an on-going path. After the handover, while the initial phase of further reform was led by top bureaucrats in a somewhat path-dependent sense, a new phase has come onto the

scene where a politics-motivated and -dominated reform agenda can increasingly be recognized. NPM reform is again used to deal with a

214 CHEUNG political problem, but within a different political and institutional context. Different motives and opportunities for change now apply, leading to different implications and limitations.

REFORMS IN THE 1990S: EMPOWERING PUBLIC BUREAUCRACY IN

POLITICAL TRANSITION

A civil service-run government has until most recently constituted a unique feature of Hong Kong’s so-called executive-led system.

Governed as a colonial administrative state before July 1997, Hong

Kong had a civil service that was both the centre of governing power and the machinery for public service delivery, whose importance had laid not only in the professionalism and meritocracy of the institution, but also the impact of its political power. During the political transition commencing from the early 1980s, both the British and

Chinese Governments had held high regard for the efficiency and effectiveness of the civil service whose stability was seen as essential to a smooth transfer of administration.

Modernization of the Colonial State since the 1970s

Although largely intact in institutional and constitutional terms, the colonial civil service had nonetheless experienced significant organizational and procedural transformation from the 1970s onwards. Apart from being attempts to modernize and open up the administration in the aftermath of the 1967 riots which revealed serious government-people gaps and rising local demands for more public services, Hong Kong’s administrative reforms were also frequently used as substitutes for political and constitutional reforms to cope with a perennial legitimacy crisis of the unelected state (Scott,

1989). Since the 1970s, there had been concurrent reforms in both the political and administrative spheres. Because of political constraints to the pace of constitutional reform 2 , such reform had moved very slowly. The reform mostly took the form of improving consultative and advisory mechanisms (e.g. the district administration scheme and introduction of partially-elected district boards of an advisory nature in the early 1980s).

The first phase of colonial administrative reform began in the mid-1970s upon the recommendation of the McKinsey & Co. whom the colonial government commissioned to review the government machinery (McKinsey & Co., 1973). A new tier of policy branches was

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 215 set up in Government Secretariat to provide policy coordination over departments. In the name of improving policy management, a theme repeated in public sector reform in the 1990s, top administrative-class civil servants, who occupied secretary posts in charge of key policy portfolios, were subject to a process of

“quasi-ministerialization.” McKinsey & Co. also recommended the streamlining of resource management processes and the adoption of new corporate thinking. The size of the civil service was expanded in line with the rapid expansion of a range of government functions, public services, and infrastructural developments. During the 1970s and 1980s, the number of government departments and quasi-governmental organizations proliferated; so had professional and specialist grades in the civil service. Greater attention was given to civil service training in line with the pronounced localization policy.

An Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC) was established in 1974 to clean up the civil service previously tarnished by both syndicated and petty corruption, especially in the police force and public works departments.

The period since the 1970s was a period of administrative reform and expansion in favor of the government bureaucracy’s growth. With improvements in salaries and conditions of service, and helped by anti-corruption efforts, the civil service was able to gain an image of efficient, clean, and well-paid workforce that could attract the best calibre in society. It became gradually accepted as a key pillar of a vibrant Hong Kong society. The efforts at modernization were in tandem with similar trends in the West--including Britain which, as

Hong Kong’s sovereign power, provided models and practices for the colonial administration to emulate--such as Management by Objective

(MBO), Planning Programming Budgeting System (PPBS), cost-benefits analysis, and corporate management. The British modernization of the civil service under the Fulton Reform was also seen to have lent inspiration for management reform in Hong Kong

(Harris, 1988).

Public Sector Reform Since 1989

The second phase of pre-1997 administrative reform, expressed as public sector reform (Finance Branch, 1989), was not just a continuation of the previous modernization process. Neither was it a passive attempt to converge with an Anglo-American-initiated NPM or

216 CHEUNG reinvention movement. In terms of rhetoric and open objectives, Hong

Kong’s public sector reform sounded like a typical NPM agenda

(Cheung, 1992, 1996a). Apart from its managerial initiatives such as budgetary devolution, contracting out and trading funds, and customer-oriented initiatives such as performance pledges, this reform was also significant in reconstituting the centre of policy management, with the policy secretaries given the powers and resources to become proper policy managers, who were able to hold various executive agencies under their respective jurisdictions

(departments, trading funds, non-departmental public bodies and public corporations) and accountable for performance and policy outcomes. The enhanced role of policy secretaries seemed to follow the NPM logic of redefining the principal-agent relationship between central policy agencies and line organizations, built upon new and more effective notions of accountability. It also pushed further the process of “quasi-ministerialization” that started in the McKinsey days. Table 1 lists major public service reforms of the pre-1997 period.

However, Hong Kong’s public sector reform did not emerge against a background analogous to a typical NPM-settings found in the West during the 1980s and early 1990s, such as oversized government, macroeconomic and fiscal crises, New Right ideology, and/or the political-party incumbency in favor of cutbacks (Hood,

1996). Whereas NPM articulated a general strategy of state contraction in order to reduce government overload, which was perceived as one of the main causes of governance failure in Western welfare states (Lane & Ersson, 1987), such a consideration rarely entered into Hong Kong’s policy decisions. On the contrary, Hong

Kong had enjoyed a healthy fiscal position and steady economic growth, with the civil service generally held in high regard by the public (Cheung, 1996a). The significance of NPM-like reforms rests not so much on the efficiency agenda, but more on a program of institutional reconfiguration to streamline policy management, service effectiveness, and customer responsiveness, at a time when the bureaucracy was subject to rising challenges from newly emerging electoral politics as well as a more demanding and vocal population that felt restless as Hong Kong entered the final stage of political transition to revert to Chinese sovereignty.

Hood (2002) has argued that the politics of public sector reforms could be understood in terms of a “public service bargain” (PSB)

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 217 between politicians and bureaucrats. Different PSBs would entail different notions of accountability, or what Hood depicts as

“blame-shifting.” Both politicians and bureaucrats are constantly engaged in a process of PSB and blame-shifting, with NPM reformers mostly presenting their doctrines as a cure to the problem of

“cheating” by bureaucratic agents on particular PSB (Hood, 2002, p.

325). In a situation where the political masters try to impose a more effective monitoring and oversight regime over the bureaucracy, and where at the same time public managers try to find their own ways of

“cheating” on the blame-shifting game, PSB would become a tug of war between the two sides and NPM reform then would be an outcome of political competition. Hong Kong in the 1990s did not yet have a politics-bureaucracy bargain per se.

Its government was run by bureaucrats who controlled agenda setting, including that for public sector reform. The bureaucracy-driven reforms mainly sought to reformulate the relationship between the central government and departments as well as to provide a new buffer of managerialism to shield top bureaucrats (whose number doubled compared to the number of ministerial officials) from societal politicization (Cheung,

1996a, 1996b).

Efficiency vs. Legitimacy Discourse of Reform

The bargain sought by NPM bureaucrat-reformers was to exchange political accountability for greater managerial autonomy.

Opting for a consumerist orientation of public service also had the advantage of re-empowering service managers through the back door

(Cheung, 1996c). Hong Kong’s pre-1997 public sector reform in terms of PSB was predominantly in favor of the bureaucracy that was able to gain new managerial legitimacy and autonomy. It was a reform that used managerial solutions to solve potentially “political” questions which could not be dealt with through proper political and constitutional reforms (e.g. by establishing a popularly mandated political executive to take policy responsibility and returning the civil service to a mainly administrative and managerial role). Underneath the official efficiency discourse was a more subtle legitimation discourse geared towards preserving bureaucratic power. Hong

Kong’s embracement of NPM does not necessarily support the convergence thesis, which is not unusual. Hood (1996) found that linguistic usage apart, the “globality” and mono-paradigmatic

218 CHEUNG character of contemporary changes in public management tended to be exaggerated.

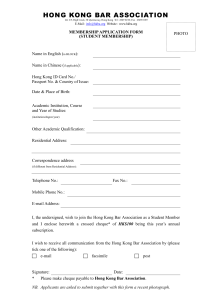

TABLE 1

Major Public Sector Reforms of the Pre-1997 Period

Period Reform measures

1970s-80s: - Setting up of ICAC (1974)

- McKinsey reform of government machinery

- Better forecasting techniques and longer term planning cycles introduced

- Introduction of value for money studies and “cash limits”

- Introduction of “controlling officer” in departments to be held accountable for expenditure

- Devolution of authority to heads of departments to create non-directorate posts subject to limits on staff numbers and salary value.

- Amalgamation of line items in budget

- Abolition of block vote arrangement for service supply departments

- Introduction of inter-departmental charging

Early to mid-1990s

- Launch of “Public Sector Reform” (1989)

- Establishment of Efficiency Unit (1992)

- Corporatization of public hospital services under new

Hospital Authority (1990)

- Setting up trading funds

- Introduction of performance pledges and customer liaison groups

- Monitoring customer satisfaction

- “Serving the Community” initiative (1995)

- Code of Access to Information

- Resource Assessment Exercise and Baseline Budgeting

- Devolution of financial resource authority to policy branches and enhancement of policy management function

- Devolution of some human resource management responsibilities to departments

- Contracting out

Late 1990s - Managing for Results

- Performance Review system

- Improving Productivity

- Private Sector Participation (including contracting out, divestiture)

- Fundamental expenditure reviews

- New management frameworks

- Reinventing front-line services

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 219

In an efficiency discourse, the problems are identified as procedural and structural defects of bureaucratic hierarchy such as productivity loss and bureaucratic waste. The solutions to these problems are reform measures of de-bureaucratization through hiving off and breaking up public bureaucracy into autonomous corporatized units emphasizing competition and performance indicators, and strengthening managerial and consumer functions. The purpose of such reform is to restore the efficiency of public sector organizations by importing private sector management methods and values. In contrast, a legitimation discourse would see the problems of government essentially as those arising from institutional failure of the bureaucratic hierarchy in “ordering” the interaction of contending interests between the state and society, between politicians and bureaucrats, between central agencies and departments, and between administrative bureaucrats and service managers/ professionals. The solution to these problems entails the restructuring of institutional relationships within the public sector environment through the interaction of “bureau-shaping” (Dunleavy,

1991) agendas of different institutional actors, in order to lead to new practices of accountability. The aim is to restore the legitimacy of the public-sector system by relying on the private-sector organizational ethos inherent in NPM methods. Precisely there has always been an implicit legitimation agenda of reform, and the changing politics of Hong Kong after 1997 triggered a different context and set of motives and objectives for government reinvention.

POST-1997 REFORMS:

REDEFINING BUREAUCRATIC PERFORMANCE AND POWER

Emerging Crises of and Challenges to Government

In the post-1997 period, the Hong Kong civil service has suffered both an efficiency and political crisis. The efficiency crisis has partly to do with various administrative and policy failures, notably in the handling of the economy and unemployment as well as the crisis management over the bird flu and SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak. The relatively high level of civil servants’ pay, compared with rapidly declining private sector wages caused by economic downturn after the Asian financial crisis, had triggered

220 CHEUNG much public debate on whether the civil service was still giving value for money. Continuing budget deficits in recent years induced the business sector and the public at large to point fingers to the rigid pay structure of civil servants whose salaries and allowances take up some 70-80% of recurrent government expenditure. Cases of civil servants’ sleaziness and misbehavior repeatedly exposed by the Audit

Commission reports have also reinforced a negative image of a workforce previously perceived to be clean, efficient, and effective.

What the civil service has suffered from is not just a crisis of efficiency. Deficiencies in efficiency, effectiveness, and probity were linked by critics to the lack of political accountability of a civil service institution that still essentially dominated the government in an

“executive-led” system until most recently. Elected legislators and appointed executive councilors began to question the supremacy and invincibility of the senior bureaucracy. Even the elite administrative class, who operates as a government cadet force and is widely assumed to have recruited the best talent in society, has faced increasing pressure to shape up.

Initially, the same strategy of pre-1997 public sector reform was pursued. Civil-service ministerial officials worked towards an

“efficiency enhancement program” (EPP) and a broad-based civil service reform as their response to public demands and political pressures. The EPP required departments to achieve savings of 5% over three years from 1999. The civil service reform proposals, launched in 1999, put contract employment and performance-related pay on the government’s agenda (Civil Service Bureau, 1999). Once again, managerial solutions were used to deal with a political crisis.

These reforms had, however, backfired by attracting vocal civil service protests in 1999 and 2000. A pay cut legislation in July 2002 further triggered the largest ever protest by public sector employees, underscoring the serious tension between government leaders and employees not seen before during colonial times.

Meanwhile a fundamental shift occurred in Hong Kong’s PSB.

The governing coalition of former Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa with top British-groomed mandarin--seen by both China and Britain as the key to continuity and stability in government at the time of the handover 3 --encountered increasing difficulties due to personality and power clashes towards the later part of his first five-year term. In this regard, he blamed his government’s failure on two main culprits: first,

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 221 the civil service at large, which was considered so inefficient and rigidly structured that it had not been able to serve him well; second, the top bureaucrats, who were seen as either not providing sufficient respect and support for his policy agenda or outright sabotaging it.

His answer to the efficiency problem was to push for more extensive civil service reform; and his solution to the political problem was to implement a new system of executive accountability for principal officials, in essence a regime of political appointment to ministerial posts to replace the senior civil servants (Tung, 2002; Burns, 2002).

In late August 2002, a four-day Management Forum was held to mark the advent of a new management style coming with Tung’s second term of office. Organized by the Efficiency Unit, it was attended by some 14,000 civil service managers. The purpose was

“to achieve a common understanding among managers in the civil service of the challenges Hong Kong and the Government now face, the vision for the future, and the roadmap for the journey ahead”

(Efficiency Unit, 2002). Three changes impacting on the civil service were identified:

- Vision delivery: The civil service had to play a crucial role to help deliver government’s vision to shape Hong Kong as Asia’s world city under the “Brand Hong Kong” initiative launched in May

2001.

- Productivity improvement: The civil service had to strive to improve the public sector productivity to meet the community’s expanding needs and rising expectations at a time of real budget constraints.

- Supporting ministers: The civil service had to adjust to the new accountability system and to work in effective partnership with the new Directors of Bureaus (i.e. the new politically-appointed policy secretaries) to help Hong Kong go from strength to strength ( ibid ).

Table 2 lists major public service reforms of the post-1997 period.

Shift in Politics-Bureaucracy Relationship

The latest phase of reform has inherent civil-service-bashing connotations. There is also a concurrent move to reduce the size of the civil service through extensive contracting out, outsourcing,

222 CHEUNG non-civil service contract appointment, and voluntary retirement. The government’s determination to review or modernize the civil service pay system and other NPM-like practices and the employees’ strong

TABLE 2

Major Public Sector Reforms of the Post-1997 Period

Period Reform measures

1997-2002 - Target-based Management Process (TMP) (1997)

- Enhanced Productivity Programme (EPP) (1998)

- Civil Service Reform (1999)

- Step-by-Step Guide to Performance measurement

2002 onwards

- New executive accountability system

- Amalgamation of some policy bureaus and subordinate departments

- Review of civil service pay adjustment mechanism

- Voluntary retirement schemes for civil servants

- Target for reducing civil service establishment

- Use of non-civil service contracts

- Private Sector Involvement (PSI) - including outsourcing and public private partnerships (PPP)

- Envelope budgeting

- 3Rs + 1M (reprioritizing, reorganizing, reengineering, market-friendly) reaction to such measures (suspecting them to be a pretext for salary cuts and layoff) clearly demonstrate the changing status of the civil service in the context of new government agenda. Under the British administration, the civil service constituted the nucleus of colonial rule and was given maximum protection in rewards and benefits.

Such a pro-civil service tradition has now become eroded because of the changing public sentiments and the coming to power of a new administration that tends to distrust the loyalty of British-groomed bureaucrats and seems eager to shift the blame for government failure to them.

Whatever PSB prevailed there in the past, appeared to have been eroded or “cheated.” Instead of relying on bureaucratic excellence as the remedy to new political shortcomings, Tung had opted for a political solution after the bureaucratic solution failed during his first term. Public service reform or reinvention was used to

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 223 legitimize both an overhaul of the civil service and a restructuring of government. In the new politics-driven phase of civil service and public sector reform with greater emphasis on contract employment, downsizing, and private sector involvement, the reform rhetoric and many of the proposed measures now seemed to conform more closely to the global NPM discourse. However, it is clear that the impetus to reform had come from domestic problems of politics and administration rather than a simple wish to emulate what other countries were doing.

Tensions and Limits in the Change Process

The reform initiatives had drawn criticism from the bureaucracy. If civil service reform implemented in economic adversity and amidst a downsizing environment had harmed the welfare and morale of the civil service (mainly middle-level and rank-and-file staff), Tung’s move towards political “ministerial” appointments had hit at the heart of the civil service—i.e., the interest and morale of the elite administrative class. Although he justified his review of executive accountability with reference to the demands of legislators and citizens for greater accountability of policy secretaries (Tung, 2000, p.

111), it was the incessant tensions and policy conflicts between him and top civil servants over the post-handover years, and his growing distrust in the mandarin team, which drove him (and the Chinese central government in Beijing) towards introducing the political

“ministerial” system previously thought undesirable.

The new ministerial system had not worked well. Since Tung’s new ministers were not elected politicians but only executive appointees of a chief executive who equally lacked a popular mandate, their political legitimacy was very much in question.

4 Yet the new ministerial team was keen to tame the civil service not only politically, but also managerially by downsizing and reorganizing it in order to produce a leaner and cheaper bureaucracy. Instead of having a highly integrated executive as in the colonial days, there were increasing signs of political-bureaucratic disjunction and conflict.

Meanwhile, the ministerial team itself was disorganized and blamed by the public for repeated policy blunders. In a sense, Tung had in his hands the worst of both worlds, which made matters worse. After mass protests by half a million people on July 1, 2003 against the proposed national security legislation and government failure, his

224 CHEUNG administration essentially became a lack duck and he was no longer able to command support. Policy-making came to a quagmire due to political uncertainty and the challenge by a growing pro-democracy opposition in the legislature after the September 2004 election. As for public sector reform, no further initiatives were launched, though government downsizing and contracting out continued to be on track.

In March 2006, Tung stepped down. He was eventually succeeded by Donald Tsang, former Chief Secretary and a long-time civil servant. Although Tsang has taken up a new “politician” profile, he is keen to groom the civil service (in particular the administrative officers) as the backbone of his administration. He accepts that political appointments are to stay and that more “outsiders” should be invited to join the government; however, at the same time, those civil servants who want to participate in politics will be allowed to leave the civil service and take up political appointments (Tsang,

2005). Whereas Tung’s project was to recruit outsiders into government, and to retain former civil servants as ministers in charge of some portfolios as a transitional arrangement, Tsang, because of his bureaucratic background, may go for a reverse direction – i.e. retaining some “outsiders” in his administration but principally relying on the Administrative Service as the source of ministerial talent from which to recruit his future ministers (and junior ministers as and when the ministerial system is expanded). If so the PSB for reform might yet undergo another change.

ANALYSIS:

THE CHANGING CONTEXT AND POLITICS OF PUBLIC SERVICE REFORM

Supply and Demand of Reform

Schedler and Proeller (2002) have argued that in all countries,

NPM reforms were initiated in reaction to current political challenges.

NPM could be construed as modernization strategies shaped in reaction to perceived challenges. There is thus a supply-and-demand explanation of it:

On the one hand, NPM delivers a supply-driven concept of theories that led to a “NPM tool-box.” On the other hand, … governments demand remedies against particular problems they are facing. The supply of instruments through NPM and the demand to counteract specific problems are matched by

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 225 varying the priority of certain NPM elements within the

[government] reform agenda” (Schedler & Proeller, 2002, pp.

163-164).

Examining the adoption of NPM by European local governments, they observe that the particular tool set a government chooses for its reform model is defined by the political circumstances it faces ( ibid :

165). The supply and demand of public sector reform in Hong Kong in the periods before and after 1997 can be identified from Table 3.

On the face of it, the current phase of reform can still be considered as a continuation of the path of the 1989 public sector reform that was started in the first place by the bureaucracy. However, the nature of reform is being transformed. Streamlining and

TABLE 3

Supply and Demand of Public Sector Reform before and after 1997

Supply-side factors

(NPM tools)

Pre-1997:

- British reform experience

(privatization, the Next

Steps, Citizen’s

Charter, etc.)

- International NPM discourse of ideas and practices

Post-1997:

- Continued spread of

NPM globally

- Consultants promoting

NPM-like tools such as contracting out and results-based management

- Business firms eager

Demand-side factors (political and institutional needs)

Pre-1997:

- Re-empowerment of civil service using managerial autonomy to confront the problem of political legitimacy

- Enhancing policy management powers of the government centre using

NPM-advocated results-based management and resource allocation to bring departments into line.

- Rising expectations of citizens for more responsive services

Post-1997:

- Economic recession and fiscal crisis

- Crises of efficiency and accountability

- Legitimation problems

- Two-pronged approach of new Chief

Executive to both revamp the civil service and to take policy management powers away from the top mandarins (by installing a new ministerial layer of

226 CHEUNG to enter into public-private partnership projects with government political appointees)

- Public and business demands to downsize the civil service and improve its cost effectiveness downsizing the bureaucracy managerially cannot now be really divorced from cutting down bureaucratic power politically. It is still early to speculate on how bureaucrats would strategically respond to this latest political challenge. It is possible that after rounds of rivalries and struggles, the two sides--ministers and bureaucrats--might settle to a new stable PSB. For the purpose of the present discussion, at least, it can be observed that Hong Kong’s administrative reform trajectory has entered a wholly new era based on a political agenda with the features discussed below.

Changing Habitat and Atmosphere

To start with, there have been significant changes in the economic, political, and institutional environment in which public sector reform takes place in the post-1997 period, which contrasts strongly with the environment in the pre-1997 period. Such changes in the habitat and atmosphere have induced new demands and a gradual change in the reform agenda.

In terms of the economic setting, the pre-1997 period was a high-growth era where the government enjoyed strong fiscal capacity that helped to support rapid expansion in both the size and functions of the public service. Cost did not really matter in those days, even though there was already an emerging concern from the late 1980s onwards, in line with the global efficiency discourse, to obtain greater value-for-money, which led to the implementation of value-for-money studies. After the Asian financial crisis in late 1997, Hong Kong entered a period of prolonged economic downturn. Although the government still possesses a good level of fiscal reserve, structural deficits have gradually become a key public and business concern.

Cost now does matter and public opinion has shifted towards doubting civil service efficiency and demanding stronger measures from the government to contain cost and reduce public expenditure.

In terms of the political setting, as explained above, the pre-1997 colonial administration was essentially government by bureaucrats. Any public service reform, from the modernization efforts of the 1970s onwards, was geared towards improving

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 227 effectiveness of bureaucratic rule and strengthening civil service capacity rather than denigrating bureaucratic power. From the 1990s onwards, the rise of electoral and legislative politics as well as the rising public expectations on service quality and accountability--both in a sense encouraged by the politics of Hong Kong’s transition from a British colony to a Chinese SAR--have undoubtedly forced the bureaucracy to shape up and become more community and customer oriented. But still the reform agenda at that time was clearly pro-civil service. The first few years after 1997 had not altered this habitat though the political atmosphere had begun to change, thanks to the repeated government crises and policy failures. The public’s growing dismay with civil service performance and resentment against high pay and rigid employment structure helped to fuel the demand for drastically revamping the bureaucracy and making the top officials more accountable for their policy outcomes. This paved the way for the introduction of the new ministerial system in July 2002, whereby the nature of government had finally shifted from that of government by bureaucrats to government by politically-appointed ministers. A politics-driven public sector reform agenda began to take shape and influenced the content and pace of reform. For the first time, some form of “public service bargain” (Hood, 2002) seemed necessary to deal with the conflicting reform motives, objectives, and strategies.

In terms of institutional setting, the pre-1997 reform incorporated a process of quasi-ministerialization of top bureaucrats as well as strengthening the government policy centre (‘policy branches’) in terms of policy coordination and resource allocation. In the SAR days, the new constitutional and political realities have induced a redefinition of minister-bureaucrat relationship since July

2002. Strengthening ministerial power and streamlining the bureaucracy have been put at the forefront of the reform agenda, alongside the more mundane efficiency goals. Some policy bureaus

(notably Education and Manpower) have proceeded to amalgamate the bureau with subordinate departments to form a new executive organization more firmly controlled by the minister. Policy management takes on both managerial and political meanings.

Shift in NPM Motives and Opportunities

In terms of motives and incentives to reform, it can be observed that despite having a long history of administrative modernization in

228 CHEUNG previous decades, at the start of public sector reforms in the early

1990s, Hong Kong did not suffer any economic or fiscal crisis, nor did it face any overwhelming political or societal pressure to undertake major institutional changes. A more vocal and active civil society had indeed emerged in the late 1980s, partly encouraged by the British attempt to develop some form of representative government as a ploy in gradual decolonization. However, public demands tended to focus on political reforms such as opening up the government and representative institutions rather than reforming public sector management per se . Indeed, when the government published its

Public Sector Reform document in February 1989, there was scant debate on its proposals in the legislature or society at large. The decision to go ahead with reform was formulated within the bureaucracy after rounds of intra-bureaucracy negotiations rather than driven by external politics.

Hence, during the 1990s, Hong Kong experienced reform by the bureaucracy for the benefit of the bureaucracy, and such reform took place in a high-growth economy which did not cause redistributive politics to creep into the reform agenda. In fact, there was concern from elected politicians and community groups that reform measures like corporatization and contracting out might lead to a deterioration of service quality. The setting up of trading funds was met with skepticism that it would lessen government responsibility for such vital public services as postal delivery. In other words, many saw the

NPM agenda as benefiting the government rather than the community. Reform was conceived or justified not within the context of denigrating civil service competence as witnessed in some NPM pioneer countries in the West, but in terms of enhancing the civil service’s primacy within a paradigm that favors bureaucratic excellence.

As such the Hong Kong NPM experience at that time probably fits better in what Hood (1996) described as the “Japanese way” – i.e. high opportunity but low motive for reform. The opportunity for reform lay in there being a relatively strong government with good fiscal health that was capable of delivering reform. However, the motive for reform was lacking because given the widely accepted perception of already having an efficient and effective civil service, the efficiency paradigm of public sector reform did not appeal well to either decision-makers or the public. Neither was the urgency of reform strongly felt. The need for change was only given lip service by civil

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 229 service managers and there were many in government who were skeptical of reform. Hence there was not a collapse of the old public administration regime in Hong Kong as observed in Western countries which created the environment for NPM (Hood, 1996). On the contrary, the administrative regime remained powerful and thriving. The reinvention of the Hong Kong public service, seen in such light, was more to re-empower public bureaucracy’s capacity.

Any trace of following the global NPM fashion could at best be regarded as policy “bandwagoning” (Ikenberry, 1990), using methods popularized by external influence to help achieve domestic ends or legitimize an agenda that addressed a domestic problem.

After the 1997 Asian financial crisis, Hong Kong has faced a prolonged economic recession and fiscal crisis for the first time in several decades. In addition there have been political and economic motives in the SAR government’s move to streamline and restructure the public sector, both to please a public that has become increasingly skeptical of government efficiency and to facilitate reframing the PSB given the widening gap between the interests of the political leadership and the bureaucracy. As a result, the economic and political habitat has supported reform motives and opened up reform opportunities similar to those experienced elsewhere, such as some OECD countries.

Renegotiating the Politics-Bureaucracy “Bargain”

We have discussed above the background to Tung Chee-hwa’s introduction of a new ministerial system in July 2002 and the ministers-bureaucrats tension arising from the political disempowerment of the elite administrative-class civil servants who until then ran the government. This obviously has an immense impact on the nature of PSB within the context of public sector reform.

Paraphrasing Moon and Ingraham’s (1998) “political nexus triad” (PNT) of the politics of administrative reform, where politics, bureaucracy, and society interacted to generate particular patterns of change, it can be argued that in the case of Hong Kong, there has been no evidence of a clear shift in public sector reform as a result of society-driven politicization, although there is arguably now a louder voice from the business sector and the public at large for reducing public expenditure and downsizing the public sector in light of

230 CHEUNG economic slowdown. Throughout the 1990s, public sector reform was essentially driven internally by the government bureaucracy which either saw it as the way to enhance bureaucratic competence and shore up its dominant governing position, or sought to adopt those reform rhetoric and skills that seemed to prove popular and somewhat effective within the global NPM context. More crucially

NPM seemed to be in congruence with the political strategy of a departing colonial administration eager to adopt a more managerial and customer-oriented style of government in order to meet rising public expectations that would not be satisfied otherwise for lack of opportunities for constitutional changes.

Such bureaucracy-led PNT had encountered difficulties and setback in the post-1997 political and economic environment.

Without belittling the enthusiasm of some senior civil servants who continued to push for a self-reforming process, it seems increasingly evident that a politicians-driven politicization was taking shape, led by pro-market allies of Tung who were skeptical of the competence and power of bureaucrats. Notably his protégé and former financial secretary Antony Leung coined the “3R + 1M” (reprioritizing, reorganizing, reengineering, and market-friendly) reinvention agenda.

The two politicization processes might share some common objectives, but were underpinned by divergent reform agendas – one to sustain bureaucratic power and the other to curb it. As a result, public sector reform entered a phase of mixed agenda with an unsettled PSB.

Under the administration of Donald Tsang who is widely expected to win a second term in 2007, a new class of “political bureaucrats” would become dominant. Bureaucrats-turned-politicians have to be more responsive to public and political demands, including entering into deals with political parties in the legislature. As such they will go for continuing public service reforms, but are unlikely to adopt any bureaucracy-bashing strategy. This should alter the path of the politics-led PNT, resulting in a hybrid that is neither hostile to the bureaucracy as in the previous phase, nor a simple return to the pre-1997 era of bureaucracy-centered self-reform.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Hong Kong’s reinvention of the public service is not just a continuation of an administrative reform trajectory that started

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 231 in colonial years in pursuit of a modernization agenda. There is no doubt that concerns for efficiency, productivity, and value-for-money have always formed part of the reform agenda at different times.

However, an efficiency discourse of reform would be insufficient for capturing the full dynamics of institutional changes in the pre-1997 and post-1997 periods. During Hong Kong’s political transition towards becoming an SAR of China in 1997, public sector reform helped to shore up the legitimacy of the bureaucracy in the face of various political pressures and challenges. Managerialism was used to serve both managerial and political purposes. After 1997, new political crises and the changing relations between the Chief

Executive and the senior civil servants had induced the advent of a new “public service bargain” which gives different meaning to the same NPM-like measures.

The Hong Kong reform experience may be unique because of the special circumstances related to the change of sovereignty and government which had impacts on the pace and scope of reform.

However, it is common in various jurisdictions that any public service reform agenda is as much shaped by political objectives and administrative expediency as economic needs and international NPM ideas. For a large part of Hong Kong’s public service reform history, the reform agenda was mooted, formulated, and implemented by the same bureaucracy which was the object of reform. This was typical of reforms by bureaucrats for bureaucrats through bureaucrats. The bureaucracy-led reform agenda did not seek to erode the power of bureaucrats, as was also the case in Singapore, for example, where a pro-state and pro-bureaucracy ethos continued to be dominant as

NPM-like reforms were pursued (Cheung, 2003).

In rhetoric, NPM reforms may help to strengthen the ministers’ policy and resource controls over the bureaucracy, but in practice the

NPM logic of managerial autonomy can conversely give the bureaucrats strong ideological grounds to resist political control and intervention. Granted this, public policy and public service framework agreements, and civil service reform packages, will become as much a design for management reforms as a political settlement to achieve a workable PSB. For Hong Kong, where until 1997 there was a stable

PSB much in favor of the bureaucracy, such political bargaining has only become a real issue with the bifurcation of the previous

232 CHEUNG administrative state into a new “political” layer and the pre-existing civil service bureaucracy, a process that is still not entirely settled.

NOTES

1. “Policy branches” were renamed “policy bureaus” from July 1997 when Hong Kong reverted to Chinese sovereignty and became a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China.

2. It was well known at the time that China was against Britain in transferring power to a popularly-elected legislature in the name of “representative government”, along the Westminster model of democracy. After Britain signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, it sought to introduce drastic constitutional reforms through the Green Paper on Representative Government. Reform measures were eventually toned down or aborted because of

China’s opposition.

3 . Tung retained the service of the Chief Secretary Anson Chan and all policy secretaries of the pre-1997 British administration in his new government formed in July 1997. The so-called Tung-Chan ticket was hailed at the time as the best way forward.

4.

Roughly half of Tung’s new ministers were former civil servants.

This arrangement was intended to help pacify the administrative class who resented being squeezed out of the power centre. A new layer of permanent secretaries was created to provide career prospect for the administrative officers.

REFERENCES

Burns, J. P. (2002). “Civil Service Reform in the HKSAR.” In S. K. Lau

(Ed.), The First Tung Chee-hwa Administration: the First Five Years of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (pp. 349-374).

Hong Kong, China: The Chinese University Press.

Cheung, A. B. L. (1992). “Public Sector Reform in Hong Kong:

Perspectives and Problems.” Asian Journal of Public

Administration, 14 (2): 115-148.

Cheung, A. B. L. (1996a). “Efficiency as the Rhetoric? – Public Sector

Reform in Hong Kong Explained,” International Review of

Administrative Sciences, 62 (1): 31-47.

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 233

Cheung, A. B. L. (1996b). “Public Sector Reform and the

Re-legitimation of Public Bureaucratic Power: The Case of Hong

Kong.” International Journal of Public Sector Management, 9

(5/6): 37-50.

Cheung, A. B. L. (1996c). “Performance Pledges – Power to the

Consumer or a Quagmire in Public Service Legitimation?”

International Journal of Public Administration, 19 (2): 233-259.

Cheung, A. B. L. (1999). “Administrative Development in Hong Kong:

Political Questions, Administrative Answers” (pp. 219-252), in H.

K. Wong and H. S. Chan (Eds.), Handbook of Comparative Public

Administration in the Asia-Pacific Basin . New York: Marcel

Dekker.

Cheung, A. B. L. (2003). “Public Service Reform in Singapore:

Reinventing Government in a Global Age.” In Anthony B. L.

Cheung and Ian Scott (Ed.), Governance and Public Sector

Reform in Asia: Paradigm Shifts or Business As Usual? (pp.

138-62). London, UK: Routledge-Curzon.

Cheung, A. B. L. (2004). “Civil Service Pay Reform in Hong Kong:

Principles, Politics and Paradoxes”, in Anthony B. L. Cheung (Ed.),

Public Service Reform in East Asia: Reform Issues and

Challenges in Japan, Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong . Hong

Kong: Chinese University Press.

Civil Service Bureau (1999). Civil Service into the 21 st Century: Civil

Service Reform Consultation Document . Hong Kong, China:

Printing Department.

Dunleavy, P. (1991). Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice:

Economic Explanations in Political Science . London, UK:

Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Efficiency Unit (2002). History of Reform [On-line]. Available: www.info.gov.hk/eu/english/history/history/history.html.

Finance Branch (1989). Public Sector Reform . Hong Kong, China:

Printing Department.

Harris, P. (1988). Hong Kong: A Study in Bureaucracy and Politics .

Hong Kong, China: Macmillan.

234 CHEUNG

Hood (1991). “A Public Management for All Seasons?” Public

Administration, 69 (1): 3-19.

Hood, C. (1996). “Exploring Variations in Public Management Reform of the 1980s.” In H. Bekke, J. L. Perry and T. A. J. Toonen (Eds.),

Civil Service Systems in Comparative Perspective (pp. 268-287).

Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hood, C. (2002). “Control, Bargains, and Cheating: The Politics of

Public-Service Reform.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 12 (3): 309-332.

Ikenberry, G. J. (1990). “The International Spread of Privatization

Policies: Inducements, Learning and ‘Policy Bandwagoning.’” In E.

N. Suleiman and J. Waterburry (Eds.), The Political Economy of

Public Sector Reform and Privatization (pp.88-110). Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Lane, J. E., & Ersson, S. O. (1987). Politics and Society in Western

Europe . London, UK: SAGE.

McKinsey & Co. (1973). The Machinery of Government: A New

Framework for Expanding Services . Hong Kong, China:

Government Printer.

Moon, M.J., & Ingraham, P. (1998). “Shaping Administrative Reform and Governance: An Examination of the Political Nexus Triads in

Three Asian Countries.” Governance, 11 (1): 77-100.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (1995).

Governance in Transition: Public Management Reforms in OECD

Countries . Paris, France: OECD.

Schedler, K., & Proeller, I. (2002). “The New Public Management: A

Perspective from Mainland Europe.” In K. McLaughlin, S. P.

Osborne and E. Ferlie (Eds.), New Public Management: Current

Trends and Future Prospects (pp.164-180) .

London, UK:

Routledge.

Scott, I. (1989). Political Change and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Hong

Kong.

Hong Kong, China: Oxford University Press.

Tsang, D. Y. K. (2005, June 3). “Campaign Speech for Chief Executive

Election.” [On-line]. Available at. http://www.donald-yktsang/ com/press_speeches_e.html. (Accessed June 4, 2005).

REINVENTING HONG KONG’S PUBLIC SERVICE: DIFFERENT CONTEXTS

AND POLITICS 235

Tung, C. H. (2000, October 11), Serving the Community, Sharing

Common Goals , Address by the Chief Executive at the Legislative

Council meeting. Hong Kong: Printing Department.

Tung, C. H. (2002). “Address to the Legislative Council on the introduction of the Principal Officials Accountability System.”

[On-line]. Available at www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/200204/17/

0417216.htm.