MICRONUTRIENTS DEFICIENCIES AND INTERVENTIONS

advertisement

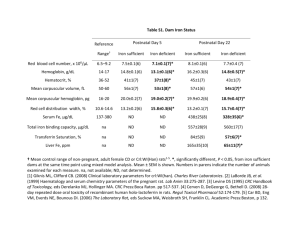

MICRONUTRIENTS DEFICIENCIES AND INTERVENTIONS A Brief Narrative of a General Review of the Nutrition and Education Literature GENERAL SUMMARY The study of malnutrition beings in the 1930’s with the investigation of kwashiorkor which based on the low protein content in many African foods, was assumed to be a protein deficiency disorder [1]. The protein deficiency hypothesis extended itself to most areas of nutritional science for the next few decades until the 1970’s with the publication of the “The Great Protein Fiasco” [2]. This debate culminated in a Nature review [3] which argued that the idea of a global ‘protein gap’, derived from the diagnosis of kwashiorkor, is no longer tenable and instead argued that energy (calorie) deficiency underlies malnutrition. A shorter period of interest in an ‘energy gap’ followed but when total calorie intake is low, intake of other nutrient is also low. Although micronutrients deficiencies were well known in their extreme form (goiter, cretinism, anemia, blindness, etc.) in the mid 1980’s milder forms of these deficiencies began to receive serious attention specifically: iodine, vitamin A and iron [4]. In 1990, UNICEF, the World Bank and WHO set the goal of eliminating these three micronutrient deficiencies by the year 2000. Essential nutrients are vitamins, minerals and other compounds that the human body needs for proper functioning yet cannot synthesize. Iron is required in almost all forms of life and plays a prominent role in human physiology as the key component of the heme group which plays a critical role in energy generation and oxygen transport (through hemoglobin and the blood). Additionally, iron plays a role in the brains dopamine system [5-7] and the behaviors it 1 generates (i.e., reward and motivation). Essential nutrients such as iron must be consumed through dietary intake. Humans acquire dietary iron in two forms: heme iron found in meats, fish and poultry and nonheme iron found in legumes and other plants. While heme iron is readily absorbed by the body at a high efficiency, nonheme iron has far lower absorption rates [8]. However other nutritional factors can influence the level of iron absorption: ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and meat can increase the absorption of nonheme iron but phytates and polyphenols often present in staple foods can inhibit iron absorption [9]. Other micronutrients such as Vitamin A can enhance the effects of iron consumption. The body carefully regulates the level of iron as too much iron can cause toxicity. In response to bacterial infection, the body can down-regulate its level of iron (since bacteria require iron from the host), thus in a sense lower iron levels can provide some protection against bacterial infection. (In some supplementation studies subjects in the treatment group were more likely to obtain infection since their bodies are now better environments for bacteria to live in, but a meta analysis shows these results may be an anomaly [10]). However, chronically low levels of iron can result iron deficiency disorders and even anemia. Iron deficiency, the most common micronutrient deficiency in the world, currently affects up to 2 billion people ~30% of the world’s populations including both the developed and developing world. A largely plant based diet, common in developing countries, contains both low quantities of easily absorbable heme iron and high quantities of inhibitors of iron absorption common in staple cereals [11]. Lack of dietary iron can lead to disorder sduring periods of high iron demand. Overall, women have higher iron demands due to menstrual blood loss and pregnancy. During periods of rapid growth, such as infancy and adolescence, demand for iron rises. These periods of developmental volatility have increased risk of iron deficiency. During 2 pregnancy, healthy mothers give a store of iron to their fetus’s while in utero and supplement it after birth with breast milk that contains iron [12]. Thus pregnant women with poor iron status will often have infants with poor iron status. High elevation can also lower body iron levels [13]. Additionally, common parasites such as hookworms and malaria can sequester available iron and cause deficiency (especially when compounded with already low iron intake) [14, 15]. Severe iron deficiency is diagnosed as anemia. The most accurate way to measure iron deficiency and anemia in a human is through a bone marrow aspiration. Since this procedure is both impractical and painful, indirect measures of iron status are used to diagnose iron deficiency disorders. Hemoglobin and ferritin levels are currently the most efficient indicators of iron deficiency when used together [16]. These measures cannot effectively distinguish between anemia in otherwise healthy individuals and anemia caused by chronic illnesses. The symptoms of iron deficiency anemia are more subtle than those of other micronutrient deficiency disorders. A mothers iron status can affect mother-child interaction and emotions [17]. Iron poor infants suffer from developmental delays such as slower motor and behavioral development [18, 19]. These early deficits only partially respond to treatment via supplementation [19, 20]. Anemic children perform worse in school and on attention tests although these results are partially confounded by the environment of the subjects [19, 21-24]. Iron deficiency decreases work performance and increases fatigue in adults [25-27]. These losses in worker capital and health have been modeled and may account for significant losses in GDP per capita [28, 29]. 3 INTERVENTION STRATEGIES FOR THE ELIMINATION OF MICRONUTRIENT DEFICIENCY [note … references are at end of this file … the references for material reviews on pages 4 to 6 begin on page 10] Three primary strategies exist for treating micronutrient deficiency: food fortification, nutritional education, and dietary supplementation. Of these options, food fortification is the most cost efficient and sustainable long term solution for improving the dietary status of impoverished peoples (Baltussen, Knai, & Sharan, 2004). However in implementing a large scale fortification paradigm, technical and infrastructural hurdles can occur. Although iodization of salt has enjoyed large scale success, finding a suitable food and micronutrient vehicle with adequate shelf-life can be difficult. Fortification of staple foods such as rice has been difficult. Under-developed infrastructure can inhibit the distribution of the fortified foods to those in need especially when the poorest populations primarily eat the food they grow. A recent intervention with NaFeEDTA fortified sodium in Bijie City, Guizhou Province greatly reduced anemia prevalence. In 3-6 year olds and 7-18 year olds anemia prevalence was reduced from 50-60% of the population to 10-20% in both males and females (Chen et al., 2005). Whether these fortified foods can reach rural populations has yet to be determined. Educational interventions can promote intake of foods with enhanced nutritional content. The educational content must align itself culturally with the given audience in order to maximize compliance. Most educational interventions target the household food provider or the person responsible for making nutritional choices for the family (often the mother). In order for an educational intervention to be successful, nutrient rich foods such as animal source food must be both available and financially accessible. A recent educational intervention in moderately malnourished children in rural Bangladesh showed that an older nutrition program improved 4 20% of children yet a newer more intensive culturally relevant program improved the nutritional status of up to 60% of children. When the intensive education group was also given supplementary feeding, up to 80% of children improved their nutritional status (Roy et al., 2005; Roy et al., 2007). Educating pregnant mother in rural Sichuan province resulted in increased infant weight after one year and better overall nutrition practices (Guldan et al., 2000). However, compliance was maintained by frequent follow up visits and reports by the mothers. If implemented correctly educational interventions ideally can prevent malnutrition rather than treat it (Dewey & Adu-Afarwuah, 2008). Dietary supplementation often takes two forms: supplementary feeding in which participants receive more/better food, and direct supplementation in which specific micronutrients are given to participants in a refined form. A hybrid approach does supplementary feeding but with specially fortified foods or animal source products. Although dietary supplementation can often be expensive, in regions where the anemia rate is high (>40%) almost the entire population is likely deficient and will thus benefit from supplementation. Direct supplementation is more cost efficient than direct feeding, but a properly implemented multivitamin requires prior knowledge of the main deficiencies prevalent in a given region (Allen, 2003). Additionally, direct supplements can be taken outside of meal times in order to optimize the level of absorption (Zimmermann & Hurrell, 2007). Indeed iron supplements eaten with food can reduce the amount of iron absorbed by 40% (Brise, 1962; Hallberg et al., 1978). High dosages of iron and other micronutrients can cause unpleasant side effects (such as gastric pain) lowering long term compliance. Supplementary feeding program may be most efficient where prevention of micronutrient deficiency is most important while direct supplementation is most efficient where treatment of deficiency is most important. Of the three intervention possibilities, 5 supplementation has the most rapid and greatest effect (over 80% reduction in anemia rates). However, the benefits of supplementation are limited to the targeted populations. Worms and other parasites such as malaria can complicate micronutrient treatment. These parasites can intensify iron deficiencies and enhance the severity of anemia (R. J. Stoltzfus et al., 1997). Micronutrient interventions are often blunted and less effective when participants have high parasite load (Rahman, Akramuzzaman, Mitra, Fuchs, & Mahalanabis, 1999; Rebecca J. Stoltzfus et al., 2004). Thus it is imperative to identify and treat parasites in parallel with micronutrient deficiencies. Different types of parasites (hookworms, malaria, etc.) may have differential effect on nutritional status (Ahluwalia, 2002). Additionally in many communities reacquisition of the parasite can occur after deworming. The WHO recommends a direct dietary intervention taken separately from meals for cost efficient treatment of micronutrient deficiency (Geneva, 2001; Rebecca J. Stoltzfus & L., 1998). These guides give a clear procedure for diagnosis, treatment and assessment of intervention paradigms. 6 Literature Review for General Summary (material from pages 1 to 3) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. Allen, L.H., Interventions for Micronutrient Deficiency Control in Developing Countries: Past, Present and Future. J. Nutr., 2003. 133(11): p. 3875S-3878. McLaren, D.S., The great protein fiasco. Lancet, 1974. 2(7872): p. 93-96. Waterlow, J.C. and P.R. Payne, The protein gap. Nature, 1975. 258(5531): p. 113-117. Bates, C.J., H.J. Powers, and D.I. Thurnham, VITAMINS, IRON, AND PHYSICAL WORK. The Lancet, 1989. 334(8658): p. 313-314. Beard, J., Iron Deficiency Alters Brain Development and Functioning. J. Nutr., 2003. 133(5): p. 1468S-1472. Erikson, K.M., B.C. Jones, and J.L. Beard, Iron Deficiency Alters Dopamine Transporter Functioning in Rat Striatum. J. Nutr., 2000. 130(11): p. 2831-2837. Beard, J., Recent Evidence from Human and Animal Studies Regarding Iron Status and Infant Development. J. Nutr., 2007. 137(2): p. 524S-530. Zimmermann, M.B., N. Chaouki, and R.F. Hurrell, Iron deficiency due to consumption of a habitual diet low in bioavailable iron: a longitudinal cohort study in Moroccan children. Am J Clin Nutr, 2005. 81(1): p. 115-121. Hurrell, R., How to Ensure Adequate Iron Absorption from Iron-fortified Food. Nutrition Reviews, 2002. 60: p. 7-15. Gera, T. and H.P.S. Sachdev, Effect of iron supplementation on incidence of infectious illness in children: systematic review. BMJ, 2002. 325(7373): p. 1142-. Zimmermann, M.B. and R.F. Hurrell, Nutritional iron deficiency. The Lancet, 2007. 370(9586): p. 511-520. Moy, R.J.D., Prevalence, consequences and prevention of childhood nutritional iron deficiency: a child public health perspective. Clinical and Laboratory Haematology, 2006. 28(5): p. 291-298. Cook, J.D., et al., The influence of high-altitude living on body iron. Blood, 2005. 106(4): p. 1441-1446. Crompton, D.W.T. and M.C. Nesheim, NUTRITIONAL IMPACT OF INTESTINAL HELMINTHIASIS DURING THE HUMAN LIFE CYCLE. Annual Review of Nutrition, 2002. 22(1): p. 35. Doherty, C.P., Host-Pathogen Interactions: The Role of Iron. J. Nutr., 2007. 137(5): p. 1341-1344. Mei, Z., et al., Hemoglobin and Ferritin Are Currently the Most Efficient Indicators of Population Response to Iron Interventions: an Analysis of Nine Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Nutr., 2005. 135(8): p. 1974-1980. Beard, J.L., et al., Maternal Iron Deficiency Anemia Affects Postpartum Emotions and Cognition. J. Nutr., 2005. 135(2): p. 267-272. Lozoff, B., et al., Preschool-Aged Children with Iron Deficiency Anemia Show Altered Affect and Behavior. J. Nutr., 2007. 137(3): p. 683-689. Grantham-McGregor, S. and C. Ani, A Review of Studies on the Effect of Iron Deficiency on Cognitive Development in Children. J. Nutr., 2001. 131(2): p. 649S-668. 7 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. Lozoff, B., et al., Poorer Behavioral and Developmental Outcome More Than 10 Years After Treatment for Iron Deficiency in Infancy. Pediatrics, 2000. 105(4): p. e51-. Pollitt, E., et al., COGNITIVE EFFECTS OF IRON-DEFICIENCY ANAEMIA. The Lancet, 1985. 325(8421): p. 158-158. Black, M.M., Micronutrient Deficiencies and Cognitive Functioning. J. Nutr., 2003. 133(11): p. 3927S-3931. Halterman, J.S., et al., Iron Deficiency and Cognitive Achievement Among School-Aged Children and Adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics, 2001. 107(6): p. 1381-1386. Pollitt, E., Iron Deficiency and Cognitive Function. Annual Review of Nutrition, 1993. 13(1): p. 521. Haas, J.D. and T.I.V. Brownlie, Iron Deficiency and Reduced Work Capacity: A Critical Review of the Research to Determine a Causal Relationship. J. Nutr., 2001. 131(2): p. 676S-690. Horton, S. and C. Levin, Commentary on "Evidence That Iron Deficiency Anemia Causes Reduced Work Capacity". J. Nutr., 2001. 131(2): p. 691S-696. Li, R., et al., Functional consequences of iron supplementation in iron-deficient female cotton mill workers in Beijing, China. Am J Clin Nutr, 1994. 59(4): p. 908-913. Horton, S. and J. Ross, The economics of iron deficiency. Food Policy, 2003. 28(1): p. 51-75. Horton, S., The Economics of Food Fortification. J. Nutr., 2006. 136(4): p. 1068-1071. Laxminarayan, R., et al., Advancement of global health: key messages from the Disease Control Priorities Project. The Lancet. 367(9517): p. 1193-1208. Baltussen, R., C. Knai, and M. Sharan, Iron Fortification and Iron Supplementation are Cost-Effective Interventions to Reduce Iron Deficiency in Four Subregions of the World. J. Nutr., 2004. 134(10): p. 2678-2684. Van Thuy, P., et al., The Use of NaFeEDTA-Fortified Fish Sauce Is an Effective Tool for Controlling Iron Deficiency in Women of Childbearing Age in Rural Vietnam. J. Nutr., 2005. 135(11): p. 2596-2601. Thuy, P.V., et al., Regular consumption of NaFeEDTA-fortified fish sauce improves iron status and reduces the prevalence of anemia in anemic Vietnamese women. Am J Clin Nutr, 2003. 78(2): p. 284-290. Andang'o, P.E.A., et al., Efficacy of iron-fortified whole maize flour on iron status of schoolchildren in Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 2007. 369(9575): p. 1799-1806. Moretti, D., et al., Extruded rice fortified with micronized ground ferric pyrophosphate reduces iron deficiency in Indian schoolchildren: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2006. 84(4): p. 822-829. Haas, J.D., et al., Iron-Biofortified Rice Improves the Iron Stores of Nonanemic Filipino Women. J. Nutr., 2005. 135(12): p. 2823-2830. Idjradinata, P. and E. Pollitt, Reversal of developmental delays in iron-deficient anaemic infants treated with iron. The Lancet, 1993. 341(8836): p. 1-4. Black, M.M., et al., Iron and zinc supplementation promote motor development and exploratory behavior among Bangladeshi infants. Am J Clin Nutr, 2004. 80(4): p. 903910. 8 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. Wasantwisut, E., et al., Iron and Zinc Supplementation Improved Iron and Zinc Status, but Not Physical Growth, of Apparently Healthy, Breast-Fed Infants in Rural Communities of Northeast Thailand. J. Nutr., 2006. 136(9): p. 2405-2411. Zhou, S.J., et al., Effect of iron supplementation during pregnancy on the intelligence quotient and behavior of children at 4 y of age: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2006. 83(5): p. 1112-1117. Wijaya-Erhardt, M., et al., Effect of daily or weekly multiple-micronutrient and iron foodlike tablets on body iron stores of Indonesian infants aged 6 12 mo: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007. 86(6): p. 1680-1686. Konofal, E., et al., Effects of Iron Supplementation on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children. Pediatric Neurology, 2008. 38(1): p. 20-26. Murray-Kolb, L.E. and J.L. Beard, Iron treatment normalizes cognitive functioning in young women. Am J Clin Nutr, 2007. 85(3): p. 778-787. Idjradinata, P., W.E. Watkins, and E. Pollitt, Adverse effect of iron supplementation on weight gain of iron-replete young children. The Lancet, 1994. 343(8908): p. 1252-1254. Ahmed, F., et al., Efficacy of twice-weekly multiple micronutrient supplementation for improving the hemoglobin and micronutrient status of anemic adolescent schoolgirls in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr, 2005. 82(4): p. 829-835. Sungthong, R., et al., Once-Weekly and 5-Days a Week Iron Supplementation Differentially Affect Cognitive Function but Not School Performance in Thai Children. J. Nutr., 2004. 134(9): p. 2349-2354. Sungthong, R., et al., Once Weekly Is Superior to Daily Iron Supplementation on Height Gain but Not on Hematological Improvement among Schoolchildren in Thailand. J. Nutr., 2002. 132(3): p. 418-422. Winichagoon, P., et al., A Multimicronutrient-Fortified Seasoning Powder Enhances the Hemoglobin, Zinc, and Iodine Status of Primary School Children in North East Thailand: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Efficacy. J. Nutr., 2006. 136(6): p. 1617-1623. Ahmed, F., M.R. Khan, and A.A. Jackson, Concomitant supplemental vitamin A enhances the response to weekly supplemental iron and folic acid in anemic teenagers in urban Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr, 2001. 74(1): p. 108-115. Ramakrishnan, U., et al., Multimicronutrient Interventions but Not Vitamin A or Iron Interventions Alone Improve Child Growth: Results of 3 Meta-Analyses. J. Nutr., 2004. 134(10): p. 2592-2602. Stoltzfus, R.J. and D.M. L., Guidelines for the Use of Iron Supplements to Prevent and Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia. International Nutritional Anemia Consultative Group, 1998. Guldan, G.S., et al., Culturally Appropriate Nutrition Education Improves Infant Feeding and Growth in Rural Sichuan, China. J. Nutr., 2000. 130(5): p. 1204-1211. 9 Literature Review for Interventions (for materials reviewed on pages 4 to 6) Ahluwalia, N. (2002). Intervention Strategies for Improving Iron Status of Young Children and Adolescents in India. Nutrition Reviews, 60, 115-117. Allen, L. H. (2003). Interventions for Micronutrient Deficiency Control in Developing Countries: Past, Present and Future. J. Nutr., 133(11), 3875S-3878. Baltussen, R., Knai, C., & Sharan, M. (2004). Iron Fortification and Iron Supplementation are Cost-Effective Interventions to Reduce Iron Deficiency in Four Subregions of the World. J. Nutr., 134(10), 2678-2684. Brise, H. (1962). Influence of meals on iron absorption in oral iron therapy. Acta Med Scand Suppl, 376, 39-45. Chen, J., Zhao, X., Zhang, X., Yin, S., Piao, J., Huo, J., et al. (2005). Studies on the effectiveness of NaFeEDTA-fortified soy sauce in controlling iron deficiency: a population-based intervention trial. Food Nutr Bull, 26(2), 177-186; discussion 187-179. Dewey, K. G., & Adu-Afarwuah, S. (2008). Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 4(s1), 24-85. Geneva, W. H. O. (2001). Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control: A guide for programme managers. Guldan, G. S., Fan, H.-C., Ma, X., Ni, Z.-Z., Xiang, X., & Tang, M.-Z. (2000). Culturally Appropriate Nutrition Education Improves Infant Feeding and Growth in Rural Sichuan, China. J. Nutr., 130(5), 1204-1211. Hallberg, L., Bjorn-Rasmussen, E., Ekenved, G., Garby, L., Rossander, L., Pleehachinda, R., et al. (1978). Absorption from iron tablets given with different types of meals. Scand J Haematol, 21(3), 215-224. Rahman, M. M., Akramuzzaman, S. M., Mitra, A. K., Fuchs, G. J., & Mahalanabis, D. (1999). Long-Term Supplementation with Iron Does Not Enhance Growth in Malnourished Bangladeshi Children. J. Nutr., 129(7), 1319-1322. Roy, S. K., Fuchs, G. J., Mahmud, Z., Ara, G., Islam, S., Shafique, S., et al. (2005). Intensive nutrition education with or without supplementary feeding improves the nutritional status of moderately-malnourished children in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr, 23(4), 320-330. Roy, S. K., Jolly, S. P., Shafique, S., Fuchs, G. J., Mahmud, Z., Chakraborty, B., et al. (2007). Prevention of malnutrition among young children in rural Bangladesh by a food-healthcare educational intervention: a randomized, controlled trial. Food Nutr Bull, 28(4), 375383. Stoltzfus, R. J., Chway, H. M., Montresor, A., Tielsch, J. M., Jape, J. K., Albonico, M., et al. (2004). Low Dose Daily Iron Supplementation Improves Iron Status and Appetite but Not Anemia, whereas Quarterly Anthelminthic Treatment Improves Growth, Appetite and Anemia in Zanzibari Preschool Children. J. Nutr., 134(2), 348-356. Stoltzfus, R. J., Chwaya, H. M., Tielsch, J. M., Schulze, K. J., Albonico, M., & Savioli, L. (1997). Epidemiology of iron deficiency anemia in Zanzibari schoolchildren: the importance of hookworms. Am J Clin Nutr, 65(1), 153-159. 10 Stoltzfus, R. J., & L., D. M. (1998). Guidelines for the Use of Iron Supplements to Prevent and Treat Iron Deficiency Anemia. International Nutritional Anemia Consultative Group. Zimmermann, M. B., & Hurrell, R. F. (2007). Nutritional iron deficiency. The Lancet, 370(9586), 511-520. 11