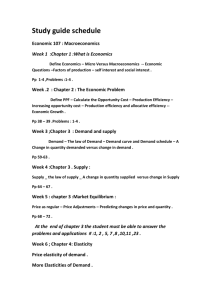

chapter 2

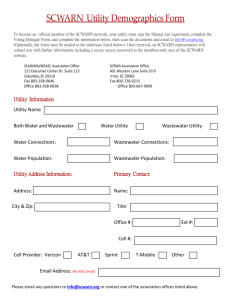

advertisement