The Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG) Practice Guideline

advertisement

The Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG) Practice Guideline

This NHG Practice Guideline is a translation of the Dutch guideline. It is specifically written for Dutch

general practitioners in the Dutch enviroment. The advice which is given may therefore not be in

accordence with the views of general practitioners in other countries.

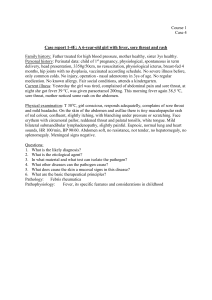

NHG Standard 'Acute sore throat'

(May 1999)

C.F. Dagnelie, S. Zwart, F.A. Balder, A.C.M. Romeijnders, R.M.M. Geijer

The standard and its scientific basis have been updated with respect to the previous

version (Huisarts Wet 1990;33:323-6). The guidelines have been revised. The most

important changes are:

The diagnostics focus on distinguishing between mild and severe throat

infections, and ruling out conditions that increase the risk of complications. The

four clinical features described by Centor [Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton

HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Dec

Making 1981;1:239-46.] help in determining the severity but are no longer used

explicitly.

In mild throat infections (or a mild form of scarlet fever), patient education is

sufficient.

In severe throat infections (or a severe form of scarlet fever) or when there is an

elevated risk of complications, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic should be used.

The current widely-accepted criterion for referral for tonsillectomy (3 episodes of

tonsillitis in one year) is not well supported; consider referral only if there have

been more than 3 episodes of tonsillitis per year, taking into account the patient's

discomfort.

INTRODUCTION

The NHG Standard 'Acute sore throat' provides guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment

of sore throat of less than 14 days duration. Sore throat caused by trauma or a foreign

body will not be covered, nor will other throat complaints, such as globus sensation or

tickling cough.

Sore throat is a very common complaint and consequently most patients with a sore

throat do not consult the general practitioner.1 2 Those who do usually have an acute

inflammation of the throat caused by micro-organisms. A small minority have a sore

throat due to non-infectious causes, such as repeated clearing of the throat, inhaling dry

air, or smoking.

1

Distinguishing between acute tonsillitis and acute pharyngitis does not affect the

treatment policy, since both involve the same pathogenesis and the inflammation has a

similar clinical course.3

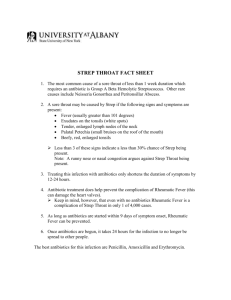

The cause is usually viral, involving one of the many common cold viruses and

sometimes the Epstein-Barr virus.4 The general practitioner will encounter the EpsteinBarr virus only a few times per year.

Bacterial throat infections probably occur more often in the select population that visits

the general practitioner than in the general population. The Group A Beta-Haemolytic

Streptococcus (GABHS) is the most important bacterial cause of throat inflammation.

Streptococci other than those in group A or Haemophilus influenzae play a modest role.5

Consequently, in this standard streptococcus will be synonymous with GABHS. Since the

late 1950s, the number of streptococcal infections with a serious clinical outcome in the

western world has decreased sharply.6 In spite of case histories reported in the

international literature concerning several streptococcal infections with a serious clinical

outcome, there are no indications of an actual increase. Furthermore, in these case

histories the throat was rarely the port of entry.

For purposes of treatment, the standard distinguishes between mild and severe throat

inflammation. Most patients with acute sore throat have a mild (viral or bacterial) throat

inflammation. Severe throat inflammation is uncommon. A severe throat inflammation is

one with severe malaise, intense throat and swallowing complaints, and greatly limited

daily functioning. It is impossible to differentiate with certainty between a bacterial and a

viral cause of the inflammation based on the clinical picture (nor, therefore, based on the

throat's appearance). Like most viral throat infections, a throat infection caused by

streptococci usually has a benign natural course, with spontaneous recovery within 7

days. Abscess formation is infrequent. Since 1998 in the western world, acute rheumatic

fever, acute glomerulonephritis, and Sydenham's chorea have become very rare

complications of a streptococcal throat infection.7 The chance that antibiotics would

prevent these complications is negligible, and about the same as the chance of a severe

anaphylactic response to penicillin.8

The course of scarlet fever also seems to be less severe than it used to be.9 Patients tend

to be less sick and complications are now rare, just as with sore throat. This has made it

less important to use the four clinical features described by Centor to distinguish viral

from bacterial causes. The question of whether or not to prescribe an antibiotic should

depend in particular on the severity of the clinical picture. The last survey of general

practitioners (in 1986) revealed that they prescribed antibiotics for 74% of patients with a

throat infection.10 Frequent prescribing of antibiotics for any and all types of throat

inflammation will only occasionally prevent abscess formation.11 Antibiotics reduce the

duration of symptoms in a streptococcal infection by an average of 1 to 2 days.12 This

limited effect does not reduce absenteeism from work and school, however. The use of

antibiotics also has disadvantages, such as side effects, development of resistance, and

medicalization (promotion of the belief that it deserves medical treatment). Whether the

use of antibiotics leads to multiple recurrences of sore throat is a matter of dispute.13

2

It is therefore recommended that antibiotics not be prescribed for patients with an acute

sore throat unless they are severely ill or have imminent complications or an elevated risk

of a complicated clinical course.14

DIAGNOSTIC GUIDELINES

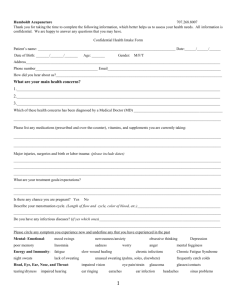

Anamnesis

In a consultation for sore throat (also by telephone), enquire about:

fever (how severe) and the severity of the illness

coughing

painful, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck

difficulty in swallowing or in opening the mouth

the duration of the symptoms and their clinical course, especially: worsening of

the pain, malaise, or swallowing complaints after 4 to 7 days

rash (scarlet fever)

acute rheumatic fever in the patient history

greatly reduced immunity

Telephone advice

In considering telephone advice, the patient should be seen if one or more of the

following are present:

severe malaise and significant limitations in day-to-day functioning

enlarged, tender lymph nodes in the neck

severe difficulties in swallowing or in opening the mouth

abnormal course (worsening of the pain, the malaise, and/or the swallowing

complaints after 4 to 7 days)

rash

acute rheumatic fever in the medical history

greatly reduced resistance, streptococcal epidemics in closed communities of

individuals in fragile health

When none of these is revealed by questioning, advice by telephone is sufficient.

Physical examination

The general practitioner notes the degree of malaise and then examines:

3

the mouth and throat:

o exudate (discharge, pus) on tonsils or pharyngeal wall

o lateral deviation of the uvula or medial deviation of a tonsil, which hinders

opening of the mouth

o erosion or ulceration in the oropharynx, petechiae on the palate (in

infectious mononucleosis)

o the condition of the teeth

the cervical lymph nodes

the skin

If the throat has been sore for more than 7 days or if the clinical course is otherwise

abnormal, the general practitioner should ask additional questions and, in certain cases,

conduct further tests or examinations.

Additional tests

Additional tests, such as a throat culture, antistreptolysin titre (AST), or an

antigen detection test (strep test) are not recommended because they will not alter

the treatment policy. When a throat culture is performed or repeated

measurements of serum AST are made, the delay in obtaining results is usually

too great for them to influence the treatment policy. Results of strep tests are

obtained rapidly but are of limited value because their predictive value for

streptococcal infection is low.15

A leukocyte count and differentiation should be performed when there is

suspicion of:

o infectious mononucleosis

o an immune system disorder such as agranulocytosis (caused by

medication) or leukaemia, as in chronically, seriously ill patients

When the differential white blood cell count is suspect for infectious mononucleosis, a

test for infectious mononucleosis can be added, such as the Paul-Bunnell test, which

measures the presence of heterophil antibodies. Serological tests should be conducted

only if the differential blood count shows the characteristic abnormalities (the laboratory

can perform these tests sequentially using the same blood sample). To reduce the chance

of false-negative results, serological tests should not be performed during the first week

of illness. If the tests are still negative while the blood count suggests infectious

mononucleosis, then cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease and toxoplasmosis must be

considered. For jaundice with infectious mononucleosis, hepatic function tests yield no

additional diagnostic information. In view of the spontaneous recovery from hepatic

function disorders after 5-6 weeks, monitoring these values over the course of the

mononucleosis infection is not meaningful. Furthermore, the clinical picture is a better

parameter for recovery. Only when hepatitis or jaundice occur as the first clinical

manifestation of a mononucleosis infection is there a clear indication for requesting

4

hepatic function tests. Measuring the ALAT level is sufficient in that case, supplemented

with bilirubin in the case of jaundice.16

Evaluation

The distinction between mild and severe throat infections is of primary importance to the

treatment policy. The four clinical features according to Centor help in determining the

severity, but are no longer used explicitly.17 This classification also applies to patients

with scarlet fever.

A sore throat is considered a mild throat infection (or mild form of scarlet fever)

in the event of:

o no severe malaise

o no enlarged, tender cervical lymph nodes

o no severe swallowing problems or problems in opening the mouth

o no abnormal course (no increase in pain, in malaise, and/or swallowing

difficulties after 4 to 7 days)

o no acute rheumatic fever in the medical history

o no signs of sharply reduced immunity

There is an elevated risk of complications in

o patients with greatly reduced immunity, as with indications of an immune

system disorder or treatment for a malignancy;

o patients with acute rheumatic fever in the medical history;

o fragile patients in closed communities during an established streptococcal

epidemic.

The problem is seen as a severe throat infection (or severe form of scarlet fever)

in the event of

o a severely ill patient (exact criteria cannot be given, but examples are

intense throat and swallowing complaints in a previously healthy patient,

significant limitations in day-to-day life due to severe malaise, high fever,

or being bedridden);

o a peritonsillar infiltrate or abscess (probable if there is lateral deviation of

the uvula or medial deviation of a tonsil together with difficulty in opening

the mouth and severe difficulty in swallowing);

o extremely swollen, painful, possibly fluctuating lymph nodes, which could

indicate infectious mononucleosis or the rare abscessing lymphadenitis

colli.

Infectious mononucleosis should be considered in patients (mainly adolescents)

with sore throat, fever, and fatigue and who have been ill for more than 7 days.18

There is usually exudate in the throat, and the lymph nodes in the neck and elsewhere are

painful and swollen. The spleen and liver may be enlarged, and in 5 to 10% of the cases

there is jaundice. Chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis of the liver do not occur as a consequence

of infectious mononucleosis. Petechiae on the palate are suggestive of the disease. The

5

diagnosis is important in order to inform the patient of the benign but sometimes

protracted clinical course. The diagnosis is certain in the presence of absolute and relative

lymphocytosis with at least 20% atypical lymphocytes in the leukocyte differentiation,

and a positive infectious mononucleosis test such as the Paul-Bunnell test. These

serological tests can be false positive and must not be interpreted independent of the other

findings.16

Other causes of sore throat, such as unhealthy habits (smoking, frequent or harsh

clearing of the throat, incorrect use of the voice), mouth breathing, inhaling dry

air or smoke or other irritants, and post-nasal drip should be considered when the

sore throat lasts for more than 7 days and is not accompanied by general illness.

Rare diseases such as herpetic or mycotic or gonococcal pharyngitis, Vincent's

angina, and diphtheria can also be mentioned for the sake of completeness.

TREATMENT POLICY GUIDELINES

Information

For a mild throat infection, the general practitioner (or the trained practice nurse) explains

that a sore throat is usually an unpleasant but harmless illness which spontaneously

disappears within 7 days. Painkillers and rest can be recommended to relieve the

symptoms. When the cause is viral, antibiotics provide no benefit. When the cause is

bacterial, antibiotics reduce the duration of the symptoms by 24 to 48 hours in some adult

patients, without reducing absenteeism from work or school. The chance that antibiotics

would prevent complications is minimal. Antibiotics also have disadvantages, such as

side effects and the development of resistance by bacteria. Consequently, penicillin is not

recommended except in the presence of a severe throat infection or an elevated risk of

complications. If the sore throat lasts for more than 7 days or if the patient becomes

increasingly ill, the patient should contact the general practitioner. When infectious

mononucleosis is confirmed or suspected, the general practitioner should explain the

benign natural course. In a minority of patients the infection leads to chronic fatigue

(weeks to months). It is not highly contagious, so special hygienic measures are not

usually necessary. Testing hepatic function has no benefit, because there is no

relationship between the severity of the disease and the degree of hepatic dysfunction,

and because within 5-6 weeks there is spontaneous recovery from these disorders and

possible jaundice. The level of illness is the best indicator for recovery. There are no

therapeutic options to shorten the time of recovery. Patient mobilization and reactivation

as soon as possible seems to be the best way to limit the dysfunction.

For scarlet fever, the general practitioner should explain that the clinical course is usually

benign and complications are rare. Although the duration of symptoms and the

contagiousness can be reduced by a few days by using antibiotics, treatment is not

necessary in milder cases.

6

For throat irritation, the doctor's advice depends on any eliciting factors, such as clearing

of the throat or smoking. Aphthae heal spontaneously in 10 to 14 days.

Medicinal treatment

A course of antibiotics for 7 days is recommended for patients with:19

a severe throat infection20

peritonsillar infiltrate or abscessing lymphadenitis

scarlet fever with severe malaise

Antibiotic treatment for 10 days (aimed at eradication of the streptococci) is

recommended for patients with21

greatly reduced immunity or acute rheumatic fever in the medical history, as soon

as there is any suspicion of a throat infection with a streptococcus.22 When there

is a potential streptococcal throat infection in the immediate environment of a

patient with a history of acute rheumatic fever, a prophylactic antibiotic course

should be considered. However, no data are available to formulate detailed

guidelines on this point.

a sore throat at the time of an established streptococcal epidemic in closed

communities with persons of fragile health, such as the elderly;

recurrent severe throat infections that do not respond well to 7-day courses of

antibiotics.

The first choice is penicillin V or phenoxymethylpenicillin (500 mg 3 dd). Children under

2 years of age are given penicillin V at a dose of 62.5 mg 3 times daily and children from

2 to 10 years are given penicillin V or phenoxymethylpenicillin at a dose of 250 mg 3 dd.

If the patient is allergic to a narrow-spectrum penicillin, erythromycin is recommended

(in adults 500 mg 4 dd, in children 30 mg/kg/day in 4 doses).23

If despite a 10-day course with a narrow-spectrum penicillin there is a recurrence,

amoxicillin/clavulanic acid could be considered as a second choice (in adults 500/125 mg

3 times daily, in children 20/5 mg/kg/dg in 3 doses) and as third choice, clindamycin (in

adults 300 mg 4 times daily, and in children 40-50 mg/kg/day in 3-4 doses).24

Follow-ups and referral

There is no need to monitor patients with an acute sore throat. It is sufficient to advise

patients to return if the symptoms worsen significantly or if they have not subsided after a

7

week. If there is a peritonsillar infiltrate, the patient should be checked after 1 to 2 days

for possible abscess formation.

When there is a peritonsillar abscess or a rare disease (confirmed or suspected) such as

abscessing lymphadenitis, sepsis, agranulocytosis, or leukaemia, the patient should be

referred.

Tonsillectomy

For recurrent severe throat infections (more than 3 per year), a referral for tonsillectomy

should be considered. However, too little good research has been done concerning the

efficacy of this for well grounded guidelines to be given. With regard to its efficacy,

however, there is not enough good research available to support guidelines. Against the

background of the benign natural course, studies conducted to date support a more

conservative approach than is common practice, in which patients are often referred for

tonsillectomy at 3 throat infections per year. In adults, tonsillectomy is major surgery

with an average sick leave of 14 days.25

note 1

Only 8-15% of patients with sore throat symptoms visit the general practitioner.

1. Bots AW. De keelontsteking in de huisartspraktijk [The sore throat in general

practice]. Leiden: Stenfert Kroese, 1965.

2. Evans CE, McFarlane AH, Norman GR, et al. Sore throat in adults: Who sees a

doctor? Can Fam Physician 1982;28:453-8.

note 2

In the Transition Project, the incidence of acute tonsillitis is 15 per 1,000 patient-years.1

The Continuous Morbidity Registration reports 19 per 1,000 for men and 23-31 per 1,000

for women.2 In a national study, comparable numbers were found for acute tonsillitis,

with a peak in the age category between 15 and 24 years.3 The incidence has declined

inexplicably over the past decades.4

1. Lamberts H. In het huis van de huisarts. Verslag van het Transitieproject [In the

doctor's house.Report on the Transition Project]. Lelystad: Meditekst, 1994.

2. Lisdonk EH, Van den Bosch WJHM, Huygen FJA, Lagro-Jansen ALM. Ziekten in

de huisartspraktijk [Diseases in general practice]. Utrecht: Bunge, 1994.

8

3. Velden J van der, Bakker DH de, Claessen AAMC, Schellevis FG. Een nationale

studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk [A national study of

diseases and procedures in general practice]. Utrecht: NIVEL, 1991.

4. Ruwaard D, Kramers PGN , eds. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning. De

gezondheidstoestand van de Nederlandse bevolking in de periode 1950-2010.

[Public Health Future Exploration. The state of health of the Dutch population

during the period 1950-2010]. Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu

[National Institute of Public Health and Environment]. The Hague: SDU, 1993.

note 3

In the literature, the term "sore throat" as a presenting complaint is used in the same way

as various clinical profiles such as acute tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and inflammation of the

throat. Similarly, etiological criteria (e.g., streptococcal pharyngitis) and clinical criteria

(e.g., tonsillar exudate) are used interchangeably. Since the mode of diagnosis varies per

country, classification problems arise and morbidity data from different countries are

poorly correlated.

For instance, in the United States, where throat cultures are carried out consistently,

"pharyngitis" (with a positive culture) is synonymous with a streptococcal throat

infection (in this text, "streptococci" is taken to mean group A beta-haemolytic

streptococci). In the Netherlands, the term pharyngitis is used primarily for viral

infections.

The ICHPPC-2 classification uses the following definitions:

I.

II.

III.

Acute upper respiratory tract infection: common cold, nasopharyngitis,

pharyngitis, and rhinitis. Both of the following criteria are required:

a.

signs of acute inflammation of the mucous membranes of the nose and

pharynx;

b.

absence of criteria indicating a more specific and otherwise classified

acute respiratory infection. This does not include influenza or other

specific diseases.

A proven streptococcal infection of the throat meets two of the following criteria:

a.

acute inflammation of the throat

b.

identified Streptococcus pyogenes

c.

increasing AST

The diagnosis of acute tonsillitis requires four of the following criteria:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

sore throat

tonsil(s) redder than the posterior pharyngeal wall

pus on the tonsil(s)

swelling of the tonsil(s)

enlarged, tender regional lymph nodes

fever

9

In this standard, as in the literature, "acute sore throat" means both acute pharyngitis and

acute tonsillitis.

Anonymous. ICHPPC-2 defined. International Classification of Health Problems in

Primary Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

note 4

Among others, the coxsackievirus and the respiratory syncytial virus are significant. Both

cause a clinical picture resembling a cold. Pathogens such as Toxoplasma gondii, the

cytomegalovirus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae are of limited

significance. Herpetic, mycotic, and gonococcal pharyngitis; Vincent's angina (ulcerative

gingivitis with necrosis and large number of anaerobic bacteria such as Borrelia vincenti)

and diphtheria are rare.1 2 3

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of Group

A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: A Practice Guideline. Clin Inf Dis 1997;25:574-83.

2. Komaroff AL, Aronson MD, Pass TM, et al. Serologic evidence of chlamydial and

mycoplasmal pharyngitis in adults. Science 1983;222:927-9.

3. Miller RA, Brancato F, King K, et al. Corynebacterium hemolyticum as a cause of

pharyngitis and scarlatiniform rash in young adults. Ann Intern Med

1986;105:867-72.

note 5

In 70% of a group of 598 patients, aged 4 to 60, with sore throat persisting for less than

14 days, Dagnelie found one or more micro-organisms in the throat culture. In 48% (of

the 598), beta-haemolytic streptococci were cultured, 32% of which were group A

streptococci and 16% of which were other streptococci. Enterobacteria were cultured in

5%, Candida albicans in 5%, Staphylococcus aureus in 4%, and various others in 8%.1

De Meyere found streptococci in 30% of a group of 670 patients aged 5 to 50, with sore

throat persisting for less than 5 days, 27% of which were group A beta-haemolytic

streptococci. Only streptococci were cultured.2 Other micro-organisms play a modest role

in throat inflammation. Streptococci of groups C and G cause no worse a clinical course

than those of group A.3

1. Dagnelie CF, Touw-Otten FWMM, Kuyvenhoven MM, et al. Bacterial flora in

patients presenting with sore throat in Dutch general practice. Fam Practice

1993;10:371-77.

2. De Meyere M. Acute Keelpijn in de eerste lijn. [Acute sore throat in general

practice.] [thesis] Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

3. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of

Streptococcal Pharyngitis: A Practice Guideline. Clin In f Dis 1997;25:574-83.

10

note 6

Acute rheumatic fever is a dreaded complication of streptococcal throat infection, due to

the secondary development of cardiac defects. In the United States, the incidence of acute

rheumatic fever has decreased spectacularly, from 25-60 per 100,000 patients per year in

the 1950s to approximately 0.49-1.88 per 100,000 patients per year around 1980. The

incidence is highest (3 per 100,000) in overpopulated cities (especially in poor, black

communities) and lowest (0.49 per 100,000) among "suburban" whites. In developing

countries the incidence is high and comparable to the 1950s level in the western

countries. Although the etiological agent—the streptococcus—is still present, acute

rheumatic fever, as the most dreaded complication, has thus virtually disappeared. The

decline in the incidence had already started before the use of penicillin: improved

hygiene and nutrition and a changing immunopathogenicity of the streptococci seem to

have played a significant role. The role that penicillin played in this decrease is probably

minor.1-6 The incidence of acute glomerulonephritis as a complication has also become

rare, estimated at 1:30,000.7

For the period 1992-1993, a survey was conducted in the Netherlands concerning the

prevalence of invasive infections of group A beta-haemolytic streptococci (GABHS).8

This led to arguments for granting epidemic status, as of early 1992, to severe invasive

infections caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (particularly types T1M1 and T3M3) and

toxic shock syndrome (TSS) in (older) adults. In view of the limited response

(documentation of only 50% of GAS isolates sent in to the RIVM [National Institute of

Public Health and Environment] for typing in the Netherlands in 1.5 years), the clinical

epidemiological data are inconclusive. Among 132 patients with invasive infections, 41

of whom had toxic shock syndrome, a pharyngitis was shown to be a known or potential

port of entry in only 7% of the cases, as in only 2% of the 323 cases in a study in Ontario,

Canada. 9 The TSS complication occurs only occasionally in individuals less than 27

years of age (while it is exactly in the age category of 5-30 years that the exudative

pharyngotonsillitis is seen most often!). In 61% of the patients evaluated, no underlying

chronic disease was reported. Furthermore, Christie rarely found a relationship to sore

throat in 60 patients with GABHS bacteraemia.10 Shulman and Dele Davies, et al.11

confirm the findings of both Schellekens8 and Christie.10 Since mid-1994 the regional

laboratories have carried out an active monitoring programme. According to an oral

report from Schellekens, there seems to have been a stabilization of severe streptococcal

infections in the Netherlands over the past few years, to a level of 1-2 per 100,000

patients per year.

Conclusion: The probable slight increase in invasive streptococcal infections is, at most,

very weakly related to sore throat. There are no indications of an increase in sore throat

from GABHS or of classical complications such as acute rheumatic fever or

glomerulonephritis.

1. Denny Jr FW. A 45-year perspective on the streptococcus and rheumatic fever:

the Edward H. Kass Lecture in infectious disease history. Clin Inf Dis

1994;19:1110-22.

11

2. Del Mar Chr. Managing sore throat: a literature review II. Do antibiotics confer

benefit? Med J Aust 1992;156:644-9.

3. Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Pract

1996;13:317-21.

4. Howie JGR, Foggo BA. Antibiotics, sore throat and rheumatic fever. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1985;35:223-4.

5. De Meyere M. Acute keel pijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice]. [thesis] Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

6. Markowitz M. The decline of rheumatic fever: Role of medical intervention. J

Pediatr 1985;106:545-50.

7. Taylor JL, Howie JGR. Antibiotics, sore throats and acute nephritis. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1983;33:783-86.

8. Schellekens JFP, Schouls LM, Silfhout A, et al. Invasieve infecties door ßhemolytische streptokokken Lancefield groep A (Streptococcus pyogenes, GAS) in

Nederland 1992-1993 [Invasive infections of Lancefield group A ß-haemolytic

streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes, GAS) in the Netherlands, 1992-1993].

Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu [National Institute of

Public Health and Environment], 1994.

9. Dele Davies H, McGeer A, Schwartz B, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal

infections in Ontario, Canada. New Engl J Med 1996;335:547-54.

10. Christie CD, Havens PL, Shapiro ED. Bacteriemia with group A streptococci in

childhood. Am J Dis Child 1988;142:559-61.

11. Shulman ST. Complications of streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J

1994;13:S70-4.

note 7

A GABHS infection heals—without treatment—within a week. The classic complications

of acute rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis have become very rare in the western

world.1-6 The incidence of acute rheumatic fever and post-streptococcal

glomerulonephritis is estimated at no more than 1:30,000 cases of sore throat.7,8

According to Hoogendoorn, it has decreased throughout the Dutch population to below

1:100,000 per year.9

1. Brink WR, Rammelkamp CH, Denny FW, Wannamaker LW. Effect of penicillin

and aureomycin on the natural course of streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis.

Am J Med 1951:300-8.

2. Dagnelie CF. Sore throat in general practice [thesis]. Utrecht: Rijksuniversiteit

Utrecht, 1993.

3. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice]. [thesis] Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

4. Del Mar C. Managing sore throat: a literature review. Med J Aust 1992;156:6449.

5. Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Pract

1996;13:317-21.

12

6. Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Reattendance and complications in a

randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect

of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ 1997;315:350-2.

7. Howie JGR, Foggo BA. Antibiotics, sore throat and rheumatic fever. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1985;35:223-4.

8. Taylor JL, Howie JGR. Antibiotics, sore throat and acute nephritis. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1983;33:783-6.

9. Hoogendoorn D. Acuut reuma en acute glomerulonefritis; huidige klinische

incidentie en de sterfte in Nederland [Acute rheumatic fever and acute

glomerulonephritis; current clinical incidence and mortality in the Netherlands].

Ned Tijdschr Geneesk 1989;133:2334-8.

note 8

Theoretically, for a sore throat with a positive streptococcus culture, penicillin would

reduce the risk of complications from acute rheumatic fever by 10-25%, so that the risk

of acute rheumatic fever would decline from less than 1:30,000 to 1:40,000.1-3 In

practice, however, that effect would be impossible to achieve; most patients with sore

throat do not consult a doctor. In the Evans study, only 8% of all sore throat patients went

to the doctor, while 8% telephoned for advice.4 Valkenburg et al. found that just 9% of

the patients with a streptococcal throat infection went to the general practitioner. In

patients who develop acute rheumatic fever or glomerulonephritis, the sore throat may be

insignificant or—in 1/3—absent.5 Sore throat patients who have acute tonsillitis or

pharyngitis are in the minority. 6

When the throat culture is positive in a patient with a sore throat, it is not easy to

distinguish the non-pathogenic, incidental presence of streptococci (carrier) from the

pathogenic presence, just from the throat culture. Even the repeated measurement of the

antistreptolysin titre does not eliminate this ambiguity. In two general practice studies,

there was insufficient titre increase in 54 and 66% of the positive throat cultures.7 8 Based

on a theoretical mathematical model, Van der Does postulates that 1 million patients

would have to take antibiotics for 10 days to potentially prevent 2 cases of acute

rheumatic fever. 9

Conclusion: The incidence of acute rheumatic fever has become so low in the western

world that the use of penicillin to prevent this complication can now scarcely be

considered significant.7 8 10 11 Glomerulonephritis has a similar incidence; the studies

available contain no evidence that penicillin prevents this disease.11 12

1. Denny FW, Wannamaker LW, Brink WR, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever.

Treatment of the preceding streptococcus infection. JAMA 1950;143:151-3.

2. Tompkins RK., Burnes DC, Cable WE. An analysis of the cost-effectiveness of

pharyngitis management and acute rheumatic fever prevention. Ann Int Med

1977;86:481-92.

3. Howie JGR, Foggo BA. Antibiotics, sore throat and rheumatic fever. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1985;35:223-4.

13

4. Evans CE, McFarlane AH, Norman GR, et al. Sore throat in adults: Who sees a

doctor? Can Fam Phys 1982;28:453-8.

5. Valkenburg HA, Haverkorn MJ, Goslings WRO, et al. Streptococcal pharyngitis

in general population. II. The attack rate of rheumatic fever and acute

glomerulonephritis in patients not treated with penicillin. J Infect Dis

1971;124:348-58.

6. Lamberts H, Wood M , eds. ICPC: International Classification of Primary care.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

7. Dagnelie CF. Sore throat in general practice [thesis]. Utrecht: Universiteit

Utrecht, 1994.

8. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice] [thesis]. Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

9. Van der Does E, Masurel N. Acute virale infecties [Acute viral infections]. Alphen

a/d Rijn: Samson Stafleu, 1988.

10. Del Mar C. Managing sore throat: a literature review. Med J Aust 1992;156:6449.

11. Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Practice

1996;13:317-21.

12. Taylor JL, Howie JGR. Antibiotics, sore throat and acute nephritis. J Royal Coll

Gen Pract 1983;33:783-6.

note 9

Van de Lisdonk EH, Van den Bosch WJHM, Huygen FJA, Lagro-Jansen ALM. Ziekten in

de huisartspraktijk [Diseases in general practice]. Utrecht; Bunge, 1994.

note 10

Based upon the NIVEL study (with data from 1986) it was calculated that general

practitioners prescribed antibiotics in 74% of the cases, 92% of the prescriptions being

for penicillin. More recent data are not available.

De Melker RA, Kuyvenhoven MM. Management of upper respiratory tract infections in

Dutch family practice. J Fam Practice 1994;38:353-7.

note 11

The estimated incidence of peritonsillar abscess is 1 in 150-200 cases of sore throat. In

his 1950 study of general practice, Bennike saw abscesses develop in 5% of his placebotreated group.1 Dagnelie found 2 abscesses in the placebo group (1.7%) and one patient

with an imminent abscess during penicillin treatment (0.8%, not significant).2 In an

English population of 8,000 general practice patients, imminent throat abscess was

14

observed on 14 occasions in 5 years. Only 3 patients had gone to the doctor in advance

with sore throat symptoms.3 The Cochrane analysis gives a relative risk of 0.19 (95% CI

0.08-0.47) for an abscess under penicillin therapy compared to placebo.4 The absolute

risk is not stated. In spite of a declining trend, peritonsillar abscess accounted for 1,152

hospital admissions in the Netherlands in 1987. It is not known how many peritonsillar

abscesses are treated by general practitioners and how many by specialists in outpatient

clinics.5 Abscessing lymphadenitis is rare. In one study, 3 cases of severe lymphadenitis

colli were reported in approximately 6,000 sore throat episodes.6

Conclusion: The incidence of abscesses is estimated to be low: 1 per 150-200; during

placebo treatment in Dutch studies it was near 1%. Usually the diagnosis of imminent

abscess is made during the initial consultation. The chances of an abscess developing

when there is a mild sore throat are minimal.

1. Bennike T, Brøchner-Mortensen K, Kjær E, et al. Penicillin Therapy in Acute

Tonsillitis, Phlegmonous Tonsillitis and Ulcerative Tonsillitis. Acta Scand

1951;139:253-73.

2. Dagnelie CF. Sore throat in general practice [thesis]. Utrecht: Universiteit

Utrecht, 1994.

3. Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Practice

1996;13:317-21.

4. Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP. Abstract of review: Antibiotics for the symptoms and

complications of sore throat. Oxford: The Cochrane library, 1998.

5. SIG, gegevens uit de Landelijke Medische Registratie van klinische opnamen in

short-stay-ziekenhuizen 1981 t/m 1987 [SIG, data from the National Medical

Record of clinical admissions to short-stay hospitals, 1981 to 1987].

6. Fry J. Acute throat infections. Update 1979;18:1181-3.

note 12

In three older studies on the effect of penicillin in general practice, a 24-hour (or less)

shortening of the duration of illness was found, usually in GABHS-positive populations,

sometimes in GABHS-negative populations.1-3 Dagnelie and De Meyere found in their

double-blind, randomized, general practice studies that only GABHS-positive patients

(32 and 27%, respectively) benefited from penicillin, with a 24-hour reduction in the

duration of illness.4,5 In an open, randomized study, Little found only marginal

improvement from antibiotics.6 It should be noted that severely ill patients were not

admitted into the latter study. (Upon inquiry, Little estimated the number to be no more

than 5%; these were mainly severely ill, bedridden patients.) According to a recent

review, antibiotics reduce the duration of symptoms by about half a day.7

In a double-blind study involving 239 patients aged 4 to 60 years with a sore throat of

less than 14 days duration and three or four Centor criteria, Dagnelie et al. found no

difference in work resumption between penicillin treatment or placebo.4 Eight percent of

the patients were excluded because in the doctor's assessment there was an absolute

indication for penicillin (imminent abscess, comorbidity requiring antibiotics, or reduced

15

immunity). In the untreated group, 2 throat abscesses occurred, compared to none in the

treated group (statistically insignificant). In the penicillin group, 31% still had throat

symptoms after 2 days (placebo group 49%). Only in patients with a subsequent positive

GABHS culture (46%) was an effect from penicillin observed: 21 of 117 patients

benefited by recovering 1 to 2 days sooner, with no difference in sick leave or work

absenteeism. After 2 days GABHS was still evident in 4% of the penicillin group,

compared to 75% of the control group.

In a group of 613 patients (with 173 GABHS-positive patients, 84 treated with penicillin

and 89 with placebo), De Meyere found a significant effect in the GABHS group only if

penicillin treatment was initiated within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms.5 All

GABHS-positive patients recovered with penicillin 24 hours earlier. The reduction in

symptoms was already easy to measure after 24-48 hours, but on the fifth day there was

no further difference from the placebo group. Here, too, no significant difference in work

absenteeism or complications was found. Patients were excluded if, amongst other things,

they had had a sore throat for more than 5 days or were at high risk.

Little et al. conducted an open, randomised study among 716 patients over 4 years of age

with sore throat and at least exudate in the throat, a red pharynx or tonsils, or swollen

neck lymph nodes.6 This design was deliberately chosen to mimic the situation in general

practice as closely as possible. Children did not have to complain of a sore throat per se;

inclusion occurred even if the symptoms were mentioned in passing. Eighty-four percent

had tonsillitis or pharyngitis. Penicillin was given to 246 patients for 10 days, while 230

just received detailed written information on the clinical course and the symptoms, and

238 just a prescription for penicillin stating that the medication could be picked up if

there was no improvement after 3 days (69% of this group did not take any penicillin).

No difference was found in illness, work absenteeism or satisfaction on day 3. In most

patients with sore throat, antibiotics only marginally improved the elimination of

symptoms: the clinical course and the impact of symptoms were not affected. In a

Cochrane review, a total of 10,484 cases of sore throat were studied, but prior selection

using the Centor criteria did not always occur, which would influence the results.7

Conclusion: For some patients with acute sore throat, penicillin reduced the duration of

illness by 1 to 2 days. This limited effectiveness is partly related to problems with respect

to the accurate selection of patients who can benefit from penicillin. The presence of

streptococci in patients with an acute sore throat does not mean the streptococci are the

cause. Moreover, clinical symptoms, a throat culture, a strep test, or AST titre can be

used within a limited time period to validate the diagnosis of a sore throat due to group A

ß-haemolytic streptococci. Severely ill patients and patients with imminent complications

or reduced resistance are excluded from most studies, based on the physician’s

assessment.

1. Whitfield MJ, Hughes AO. Penicillin in acute sore throat. Practitioner

1981;225:234-9.

2. Randolph MF, Gerber MA, De Meo KK, et al. Effect of antibiotic therapy on the

clinical course of streptococcal pharyngitis. J Pediatr 1985;106:870-5.

16

3. Haverkorn MJ, Valkenburg HA, Goslings WRO. Streptococcal pharyngitis in the

general population. I. A controlled study of streptococcal pharyngitis and its

complications in the Netherlands. J Inf Dis 1971;124:339-47.

4. Dagnelie CF, Van der Graaf Y, De Melker RA, Touw Otten FWMM. Do patients

with sore throat benefit from penicillin? A Randomized double-blind placebocontrolled clinical trial with penicillin V in general practice. Br J Gen Pract

1996;46:589-93.

5. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice] [thesis]. Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

6. Little P, Williamson I, Warner G, et al. Open randomised trial of prescribing

strategies in managing sore throat. BMJ 1997;314:722-7.

7. Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP. Abstract of review: Antibiotics for the symptoms and

complications of sore throat. Oxford: The Cochrane Library, 1998.

note 13

Disadvantages of the use of penicillin are:

allergic reactions, the risk being approximately 1 to 2%. An anaphylactic reaction

occurs in 10 to 40 per 100,000 intramuscular administrations, with a resultant risk

of death of 2 per 100,000. With oral administration the reactions are less frequent

and less violent;1-6

selection of resistant micro-organisms, especially when broad spectrum

antibiotics are used;7-9

potentially reduced rise in specific antibodies, particularly in children; 9 10

increased chance of a recurrence: three studies compared immediate treatment

with penicillin to a 2-day delayed treatment. Immediate treatment was found to

increase the rate of recurrence by 20%;10-12

medicalizing effect: prescribing antibiotics increases the probability of a

consultation in the event of a recurrence of sore throat symptoms.13

1. Haverkorn MJ, Valkenburg HA, Goslings WRO. Streptococcal pharyngitis in the

general population. I. A controlled study of streptococcal pharyngitis and its

complications in the Netherlands. J Inf Dis 1971;124:339-47.

2. Anonymus. Continue morbiditeitsregistratie peilstations [Continuous Morbidity

Registration Sentinel Stations]. Utrecht: Nederlands Huisartsen Instituut, 1983.

3. Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR et al. Nature and extent of penicillin side-reactions

with particular reference to fatalities from anaphylactic shock. WHO Bull

1968;38:159-88.

4. Young E. Allergie voor penicilline [Penicillin allergy]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd

1985;129:1713-6.

5. Erffmeyer JE. Adverse reactions to penicillin. A review. Ann of Allergy

1981;47:288-300.

6. Del Mar Chr. Managing sore throat: a literature review. Med J Austr

1992;156:644-9.

17

7. Arason VA, Kristinson KG, Sigurdsson JA, et al. Do antimicrobials increase the

carriage rate of penicilline resistant pneumococci in children? Cross sectional

prevalence study. BMJ 1996;313:387-91.

8. Lacey RW. DNA in Medicine. Evolution of microorganisms and antibiotic

resistance. Lancet 1984;2:1022-5.

9. Komaroff AL. A management strategy for sore throat. JAMA 1978;239:1429-32.

10. Pichichero ME, Disney FA, Talpey WB, et al. Adverse and beneficial effects of

immediate treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis with

penicillin. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987;6:635-43.

11. El-Daher N, Hijazi S, Rawasdeh N, et al. Immediate versus delayed treatment of

group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis with penicillin-V. Ped Inf Dis J

1991;10:126-30.

12. Gerber M, Randolph M, Demeo K, Kaplan E. Lack of impact of early antibiotic

therapy for streptococal pharyngitis on recurrence rates. J Pediatr

1990;117:853-8.

13. Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Reattendance and complications in a

randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect

of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ 1997;315:350-2.

note 14

When penicillin is prescribed, usually one of the following is intended: to reduce the

duration of illness or accelerate eradication of symptoms; to prevent abscess formation,

acute rheumatic fever, and glomerulonephritis; or to eradicate GABHS in the throat more

rapidly, with the aim of reducing and curtailing the danger of infection within 24 hours.

In the decision analysis by Touw-Otten et al., in which a higher risk of recurrence was

not considered, the conclusion was: in a patient without elevated risk, who has had a sore

throat for less than 48 hours, a narrow-spectrum penicillin taken orally should be

considered if the four Centor clinical criteria are present. If three criteria are present, a

rapid strep test could be performed, after which penicillin is only given if the result of the

strep test is positive. If no strep test is available, symptomatic therapy is preferred.

Antibiotic therapy not indicated when there are less than three criteria, nor in the case of

a sore throat that has lasted more than 48 hours, unless in a patient at an elevated risk.1

De Meyere is of the opinion that the benefits do not outweigh the numerous, at times

serious, adverse effects.2 Little claims that the chance that a general practitioner would

cause a fatal anaphylactic response in the course of his career by treating every acute sore

throat with penicillin (estimated to be 1 in 3 to 1 in 14) is equal to the chance of seeing a

patient who develops glomerulonephritis or acute rheumatic fever after a sore throat.3 Del

Mar states that the frequency of acute rheumatic fever is too low, protection against

abscesses too marginal, and the reduction of symptoms in sore throat too minimal to

justify the use of antibiotics.4 5

18

In addition, treatment with antibiotics is indicated at an earlier stage in patients with sore

throat who are at an elevated risk due to sharply reduced resistance or acute rheumatic

fever in the history (if those patients are not already taking prophylactic antibiotics).

1. Touw-Otten F, De Melker RA, Dippel DWJ, et al. Antibioticabeleid bij tonsillitis

acuta door de huisarts; een besliskundige analyse [Antibiotic treatment policy for

acute tonsillitis in general practice; a decision analysis]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd

1988;132:1743-8.

2. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice] [thesis]. Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

3. Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Pract

1996;13:317-21.

4. Del Mar Chr. Managing sore throat: a literature review. Med J Aust

1992;156:644-9.

5. Del Mar CB, Glasziou PP. Abstract of review: Antibiotics for the symptoms and

complications of sore throat. Oxford: The Cochrane Library, 1998.

note 15

In the antigen detection test (strep test), streptococci can be detected within 5 to 20

minutes by means of an enzyme-linked immune response. The sensitivity of the strep test

compared to the throat culture has varied in different patient populations from 44 to 96%,

with a mean of about 80%. The positive predictive value is over 90%.1 In Dagnelie's

study, in all patients, the sensitivity of the strep test was 65%, the specificity 96%, the

positive predictive value 88%, and the negative predictive value 85%, with the throat

culture as the golden standard.2 In the group of sore throat patients who had three or four

Centor criteria, the sensitivity of the strep test was 75% compared to the throat culture.2

Considering those characteristics, the strep test has some added (albeit limited) value

after clinical selection using the Centor criteria. Specifically, despite clinical indications

for the use of antibiotics, a negative test further supports a conservative approach to

antibiotic use. Precise determination of the value is difficult, due to the limits of both a

throat culture and increasing antistreptolysin titres (see below). There are new rapid tests

available.4 Their value has not yet been adequately demonstrated.5 If penicillin use is

being considered in a patient with the four Centor criteria, the patient and the general

practitioner will primarily be interested in the chance of shortening the course of the

disease by use of penicillin and not so much interested in the possibility of prescribing

penicillin wrongly. Several studies found that penicillin was often prescribed even when

the strep test was negative. Apparently, given the chances of a false negative test, clinical

considerations were the deciding factor in the decision to fight a potential streptococcal

infection anyway, in spite of the low possibility.1 6 7

The throat culture is no gold standard for a streptococcal infection: there is a

streptococcal carrier state, in which there is no relationship between the presence of

streptococci in the culture and sore throat symptoms (in approximately 10% of the

population); furthermore, about 10% of the throat cultures are false negative. Newer

culturing techniques may have more validity.

19

Even increased antistreptolysin titres (AST) are no longer seen as the gold standard.

When the throat culture is positive, only about half of patients show an increase in the

antistreptolysin titres. Treatment with penicillin can suppress the AST increase, and when

the interval between the measurements is too short, a possible increase in the antibody

titres may not be measurable. Although an increase in antibody titres is no longer the gold

standard, there is no agreement on a different standard.2,8 With these limitations, a strep

test adds too little to justify its introduction into general practice. Moreover, extra

diagnostics can raise false expectations, causing patients to come back sooner.

1. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice] [thesis]. Gent; Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

2. Dagnelie CF, Bartelink ML, van der Graaf Y, et al. Towards a better diagnosis of

throat infections (with group A ß-haemolytic streptococcus in general practice. Br

J Gen Pract 1998;48:959-962.

3. True BL, Carter BL, Driscoll CE, et al. Effect of a rapid diagnostic method on

prescribing patterns and ordering of throat cultures for streptococcal pharyngitis.

J Fam Pract 1986;23:215-9.

4. Gerber MA, Tanz RR, Kabat W, et al. Optical immunoassay (O.I.A.) for group A

ß-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. JAMA 1997;277:899-903.

5. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM. Diagnosis and management of group A

streptococcal Pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Clin Inf Dis 1997;25:574-83.

6. Dagnelie CF, De Melker RA, Touw-Otten F. Wat heeft een streptest huisartsen te

bieden? Toepassing van de streptest tijdens de testfase van het keelpijnprotocol

[What can a strep test offer to general practitioners? Use of the strep test during

the test phase of a sore throat protocol]. Huisarts Wet 1989;32:407-11.

7. Burke P, Bain J, Cowes A, Athersuch R. Rational decisions in managing sore

throat: evaluation of a rapid test. BMJ 1988;296:1646-9.

8. Gerber MA, Randolph MF, Mayo DR. The group A streptococcal carrier state. A

reexamination. Am J Dis Child 1988;142:562.

note 16

A Paul-Bunnell reaction gives the greatest certainty, but the antibodies are not always

detectable: in the first week of illness, the chance of a negative test is 60% and in the

second week it is still 20%. False positive reactions also occur.1

Almost all patients with mononucleosis have slight liver dysfunction, and 5-10% have

jaundice. The general practitioner often requests hepatic function tests.2 There is no

correlation between the severity of the symptoms and the degree of liver dysfunction. The

liver dysfunction always heals spontaneously after 5 to 6 weeks, with the peak of the

abnormalities in the tests usually occurring in the second week. Chronic hepatitis or

cirrhosis of the liver do not occur as a result of infectious mononucleosis.3

1. Schellekens JWG. Mononucleosis infectiosa (Uit de serie Huisartsgeneeskundige

conferenties) [Infectious mononucleosis (From the series: General Practice

Conferences)]. Huisarts Wet 1980;23:189-92.

20

2. Zaat JOM, Schellevis FG, Van Eijk JthM, Van der Velden J.

Laboratoriumonderzoek bij klachten over moeheid. In: Zaat JOM. De macht der

gewoonte; over de huisarts en zijn laboratoriumonderzoek [Laboratory research

for fatigue complaints. In: Zaat JOM. The power of habit: on general

practitioners and their laboratory tests] [thesis]. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit,

1991.

3. Drenth JPH, Pop P, Van Leer JVM. Diagnostiek van mononucleosis infectiosa

[The diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis]. Practitioner (Ned) 1988:361-6.

note 17

Centor analysed 14 characteristics for the degree to which they contributed to the

diagnosis of streptococcal throat infection in 286 adults visiting a Casualty Department

with the complaint of a sore throat. Four appeared to be significant: (recent) fever,

tonsillar exudate, swollen and tender anterior cervical lymph nodes, and the absence of a

cough. The chance of a positive throat culture proved to be 56% if all four of these

characteristics were present, 32% if three were present, and 15% if two were present.

Hence the presence of these four "classic" characteristics does not confirm the diagnosis

of a streptococcal infection.1 In children under 15 years of age, the same characteristics

proved to be irrelevant with regard to the possibility of a streptococcal infection. In this

age group, the chance of a streptococcal carrier state is much higher than in adults. Under

4 years of age, the symptoms are often more vague and streptococcal infections occur

less frequently.2 3 4

Conclusions:

A viral infection is probable when there is coughing and/or a duration of greater

than seven days in combination with fever and malaise.

The chance of streptococci being found is about 50% in the presence of all four

Centor criteria: absence of cough, fever ³38.5oC (rectally), swollen and tender

lymph nodes in front of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and exudate in the throat.

In sore throat patients under 15 years of age, the chance of streptococci being

present in the throat is about 50%, regardless of other attendant clinical

symptoms.

1. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in

adults in the emergency room. Med Dec Making 1981;1:239-46.

2. Breese BB. A simple scorecard for the tentative diagnosis of streptococcal

pharyngitis. Am J Child Dis 1977;131:514-7.

3. Dagnelie CF. Sore throat in general practice [thesis]. Utrecht: Universiteit

Utrecht, 1994.

4. De Meyere M. Acute keelpijn in de eerste lijn [Acute sore throat in general

practice] [thesis]. Gent: Rijksuniversiteit Gent, 1990.

note 18

21

In adolescents with a sore throat persisting for more than 7 days together with fever,

fatigue, and swollen lymph nodes, infectious mononucleosis should be considered.1 2

Infectious mononucleosis occurs in an average of 1 per 1,000 patients per year,

particularly in adolescents and young adults, and somewhat more often in women. The

infection only rarely occurs in two or more family members at the same time, so it has a

relatively low contagiousness. In children, infectious mononucleosis usually results in an

atypical viral clinical picture.3 4 Extremely rarely, complications such as

encephalomeningitis and ruptured spleen can occur.3-6

1. Schellekens JWG. Mononucleosis infectiosa (Uit de serie Huisartsgeneeskundige

conferenties) [Infectious mononucleosis (From the series: General Practice

Conferences)]. Huisarts Wet 1980;23:189-92.

2. McSherry JA. Diagnosing infectious mononucleosis: avoiding the pitfalls. Can

Fam Physician 1985;31:1527-9.

3. Van de Lisdonk EH, Van den Bosch WJHM, Huygen FJA, Lagro-Jansen ALM.

Ziekten in de huisartspraktijk [Diseases in general practice]. Utrecht: Bunge,

1994.

4. Sutton RNP. Clinical aspects of infection with the Epstein-Barr virus. J R Coll

Physicians Lond 1975;9:120-8.

5. Domachowske JB, Cunningham CK, Cummings DL, et al. Acute manifestations

and neurologic sequelae of Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis in children. Pediatr

Infect Dis J 1996;15:871-5. 4.

6. Connelly KP, DeWitt D. Neurologic complications of infectious mononucleosis.

Pediatr Neurol 1994;10:181-4.

note 19

In 1953 the American Heart Association Council on Rheumatic Fever and Congenital

Heart Disease recommended that oral penicillin be prescribed for 10 days in the presence

of a proven streptococcal throat infection. This recommendation was based on various

studies showing that after a 5-day course of treatment, more bacteria remain present in

the throat than after a 10-day course.1 2 These findings were confirmed in prospective

studies, which additionally showed that the clinical symptoms returned more often after a

7-day course than after a 10-day course.3-5

The standard distinguishes between a 7-day and a 10-day course of antibiotics. If such a

course is intended, then a 7-day course will be sufficient to bring about clinical recovery.

If specific prevention of the classic complication acute rheumatic fever is intended, then,

in theory, eradication of streptococci by means of a 10-day course is the best way to

achieve that goal.

1. Breese BB, Bellows MT, Fischel EE. Prevention of rheumatic fever. Statements of

American Heart Association council on rheumatic fever and congenital heart

disease. JAMA 1953;151:141-3.

22

2. Wannamaker LW, Denny FW, Perry WD, et al. The effect of penicillin

prophylaxis on streptococcal disease rates and the carrier state. N Engl J Med

1953;249:1-7.

3. Schwartz RH, Wientzen RL, Pereira F et al. Penicillin V for group A

streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis. A randomized trial of seven vs. ten days'

therapy. JAMA 1981;246:1790-5.

4. Gerber MA, Randolph MF, Chanatry J, et al. Five vs ten days of penicillin V

therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis. Am J Dis Child 1987;141:224-7.

5. Kaplan EL. The group A streptococcal upper respiratory tract carrier state: an

enigma. J Pediatr 1980;97:337-45.

note 20

Severely ill patients are excluded from most trials and treated with penicillin. A precise

description of this group of severely ill patients is not given (see note 12). It is therefore

unknown precisely how significant the effect of penicillin in this - poorly described group is. The risk of purulent complications seems greater, and the need to reduce

symptoms is evident. Therefore, the committee is of the opinion that curative and

prophylactic treatment is indicated for patients with a severe throat infection.

note 21

The endocarditis prophylaxis is specifically aimed at preventing infection by

Streptococcus viridans in interventions on patients with heart valve insufficiencies and a

previous history of endocarditis. Yet there is no relationship between throat infections

and endocarditis from Streptococcus viridans. Fever in and of itself is not an indication

for administering antimicrobial therapy.1

In patients with artificial joints and a 'significant risk' of bacteraemia, for example in

(skin) infections in the same extremity, antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial arthritis is

recommended by the professional groups. Kaandorp's study found that the chances of

complications from antibiotic treatment could be greater than the chance of a bacterial

infection from the artificial joint. There is limited efficacy, particularly for skin infections

in patients who also have the following characteristics: an artificial joint, rheumatoid

arthritis, age over 80 years, and an additional disease such as diabetes mellitus or cancer.

With regard to throat infections, the efficacy is even less. Furthermore, throat infections

from streptococci are rare in individuals over 65 years of age.2 The general practitioner

will always consider prophylaxis with antibiotics when (rare) clustering of the

aforementioned risk factors occurs, based on the diabetes mellitus and advanced age. In

patients with an artificial joint and a bacterial skin infection, there are arguments for

administering prophylaxis; in patients with an artificial joint and a throat infection, there

is too little support to recommend prophylactic antibiotics. 2

23

1. Anonymous. Preventie bacteriële endocarditis [Prevention of bacterial

endocarditis]. Revised publication February 1996. The Hague: De Nederlandse

Hartstichting {Dutch Heart Foundation], 1996.

2. Kaandorp CJE. Prevention of bacterial arthritis [thesis]. Amsterdam: Vrije

Universiteit Amsterdam, 1998.

note 22

The decision to give antibiotics in the event of any suspicion of a streptococcal infection

is based on a consensus within the committee; no information on this was found in the

literature.

note 23

Until now, the superiority of other antibiotics, such as the cephalosporins, has not been

proved conclusively. Penicillin has been demonstrated to be effective, relatively safe, and

inexpensive, and has a narrow spectrum. When there is a narrow-spectrum penicillin

allergy, a macrolide such as erythromycin can be prescribed, based on the activity

spectrum.1 2

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of group

A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Clin Inf Dis 1997 25:574-83.

2. Pichichero ME, Disney FA, Talpey WB, et al. Adverse and beneficial effects of

immediate treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis with

penicillin. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987;6:635-43.

note 24

Most studies on recurrent throat infections assume 10 days of treatment with antibiotics,

aimed at eradication.1-3 There are no well-controlled comparative studies on the

effectiveness of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and other antibiotics. There are, however,

indications that ß-lactamase-producing strains of anaerobic bacteria sometimes protect

the Streptococcus pyogenes against penicillin, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid is effective

against this. Where a clinical basis is lacking, there is some consensus in the literature for

using clindamycin as third choice, in view of its effectiveness for eradication.1 4

1. Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of group

A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Clin Inf Dis 1997;25:574-83.

2. Brook I. Treatment of patients with acute recurrent tonsillitis due to group A ßhaemolytic streptococci: a prospective randomized study comparing penicillin

and amoxi/claviculanate potassium. J Antimicrob Chem 1989;24:227-33.

3. Kaplan EL, Johnson DR. Eradication of group A streptococci from the upper

respiratory tract by amoxicillin with clavunalate after oral penicillin V treatment

failure. J Pediatr 1988;113:400-3.

24

4. Orring A, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Schalen C. Clindamycine in recurrent group A

streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis - an alternative to tonsillectomy. Acta

Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1997;117:618-25.

note 25

Tonsillectomy is performed preventively in 1 per 100 children each year (91.5% of

children up to 14 years). Parallel to the international trend, the number of tonsillectomies

in the Netherlands decreased by 2/3 since 1976, with the Netherlands remaining far ahead

internationally.1

Paradise et al.2 performed an 11-year prospective study in children, which used strict

inclusion criteria for children with only clinically objectifiable episodes of tonsillitis: 7

episodes of tonsillitis in the past year, or 5 per year in 2 years, or 3 per year in 3 years. An

episode of tonsillitis had at least the following symptoms: fever > 38.3 degrees, or

cervical lymphadenopathy, or exudate on the tonsils or the pharynx, or a positive throat

culture for ß-haemolytic streptococci. Among 2,043 patients, only 187 were included. Of

those, 91 children were randomized for either an adenotonsillectomy or a 'wait-and-see'

approach with antibiotic treatment for throat infection. The other 96 were subdivided

according to their parents' preference. In the first two years after the operation, there was

a reduction in the number of throat infections in the ATE group compared to the nonoperated group of 1 versus 3 episodes (measured by means of questionnaires). After 2

years, the difference was no longer significant (1 vs. 1.7 episodes). In this study, the

parental anamnesis was very unreliable.3 The effectiveness of tonsillectomies appeared to

be greatest in the category of mild throat infections: the unblinded nature of the study

could result in bias particularly in this group. In the first year, there was a difference of 3

days in school absenteeism between the two groups, and in the second year a difference

of 1.5 days. This study confirmed the results of previous studies of lesser quality.4 5

In 1990 in the Netherlands the mortality from adenotonsillectomy was estimated to be 1

in 74,000. The percentage of secondary bleeding was between 0.1 and 8.1%.6 The

impression given by at least 75% of parents was that their child's condition improved

following adenotonsillectomy. This has not been specifically studied in the Netherlands,

but the general impression is that parents are very satisfied with its results. International

studies strongly support this conclusion.7 8 A tonsillectomy in adults requires an average

of 14 days of sick leave from work.9 10

1. Hoogendoorn D. Schattingen van de aantallen tonsillectomieën en adenotomieën

bij kinderen [Estimates of the number of tonsillectomies and adenotomies in

children]. Ned Tijdschr Geneesk 1988;132:913-5.

2. Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. Efficacy of tonsillectomy for

recurrent throat infection in severely affected children. New Engl J Med

1984;310:674-83.

3. Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Bachman RZ, et al. History of recurrent sore throat

as an indication for tonsillectomy. New Engl J Med1978;298:409-13.

25

4. Mawson S, Adlington P, Evans M. A Controlled study evaluation of adenotonsillectomy in children. J Laryngol Otol 1967; 81: 777- 790.

5. Roydhouse N. A Controlled study of adenotonsillectomy. Arch Otolaryng

1970;92:611-6.

6. Hammelburg E. Honderd jaar knippen en pellen. In: Honderd jaar kopzorg,

Gedenkboek bij het eeuwfeest van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Keel-NeusOorheelkunde en Heelkunde van het Hoofd-Halsgebied [A century of

tonsillectomies. In: A century of headiness: Commemorating the Centennial of the

Dutch Association for Otothinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery]. Utrecht

1993:37-48.

7. Conlon BJ, Donnelly MJ, McShane DP. Improvements in health and behaviour

following childhood tonsillectomy: a parental perspective at 1 year. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol 1997;41:155-61.

8. Blair RL, McKerrow, WS, Carter NW, Fenton A. The Scottish tonsillectomy audit.

J Laryngol Otol 1996; suppl 20:1-25.

9. Murthy P, Laing MR. Dissection tonsillectomy: pattern of post-operative pain,

medication and resumption of normal activity. J Laryngol Otol 1998;112:41-4.

10. Mehanna HM, Kelly B, Browning GG. Disability and benefit from tonsillectomy

in adults. Clin Otolaryngol 1998;23:284.

© Copyright NHG 2002

disclaimer

26